Trippelganger

An artist, an astrophysicist, and a psychoanalyst have dinner

Leon Golub, Leon Golub, and Leon Golub

In May 2002, Cabinet called a car service company to arrange for three men to be picked up at various spots in Manhattan that evening and brought to a dinner at the magazine’s Brooklyn offices. Placing the order was not simple. This was not because the three men were in any way notorious or dangerous—one was an established psychoanalyst with a practice in New York City, one was a Harvard University astrophysicist, and the third was an internationally known artist. What made the car service suspect that our call was a prank was that each man had the exact same name—Leon Golub. While they ate, the three Leons got to know each other, talking about everything from their professions to the ways in which their shared name had already intertwined their fates. Below is an edited version of the discussion between the artist (A), the psychoanalyst (P), and the scientist (S).

A. I’m into popular books on cosmology.

S. These days I study the sun and I have brought a photo for you all. What you’re looking at in the photo is x-rays, light that’s actually invisible. This is what’s above the visible surface of the sun and it’s so hot, millions of degrees, that the light it puts out is x-rays.

A. X-rays are shortwave?

S. Yes. So, to get that image you have to put a telescope up above the atmosphere because x-rays are absorbed by the atmosphere.

P. How do you get the photo?

S. From a small satellite that NASA put up. Typically, the way you learn about solar activity is by making movies out of the data to see how things change. The bright areas especially tend to explode and send stuff out into space, and it’s weird the way it comes crashing down on us.

A. Like meteors?

S. It’s actually hot magnetized plasma.

P. Do we know about it when it happens?

S. The main thing that people know about it is the northern lights, but you can also get destructions of the power grid. It was a solar event that caused a huge surge in the Canadian wires in 1989 and made the transformers blow up.

P. [to the artist]. You wouldn’t get that in the books you’re reading on cosmology. You’re not keeping up with the current stuff.

A. The stuff I’m reading now doesn’t deal with such local phenomena ...

[Laughter].A. Multiple universes, now that’s the big stuff!

P. I read some of your book on the sun and you know, in part of it you kind of scared me, where there was the suggestion that we should worry about the sun.

S. Well, we should make sure we understand it. If you take away the sun, the earth would freeze over solidly, the temperature would go down close to absolute zero. And if we get any closer to the sun, or the sun gets brighter, it’ll be much hotter here. So we’re in a real delicate balance between freezing and boiling.

A. There isn’t much chance of it happening?

S. The sun will eventually swallow the earth.

A. Eventually, yes.

S. But we’ve got some time.

A. We’ve got a little time.

[Laughter].S. I guarantee that humans won’t be around by the time that happens.

A. I’ll tell this joke, but it’s corny. A student is sort of half-asleep in class. Suddenly he jumps up and says, “What did you say?” and his professor says “Uhh, the sun will go out in six billion years.” And the student says, “Phew, I thought you said six million.”

[Laughter].P. There’s a joke going around that you just reminded me of. Somebody asks God, “What’s a million years to you?” and God says, “It’s like a second.” And then he says, “What’s a million dollars to you?” and God says, “Well, it’s like a cent.” Well, the man says, “Can you give me a cent?” And God says, “Just a second.”

[Laughter].S. Very good.

P. I’ve got a lot of God jokes. You know, you’ve reminded me of my astrophysicist joke. [to scientist]. You must know it. This astrophysicist and his chauffeur are traveling around giving seminars… [to scientist]. You know it? It’s a real classic. Can I tell it anyway?

S. It’s one of my favorite stories, actually.

P. Do you want to tell it? Why don’t you tell it?

S. The way I heard it is that this physicist gets a Nobel Prize and he’s asked to go over and give a lecture about it. He devises a lecture and he gives the same one each time and he’s got a chauffeur that brings him around to the various places; the chauffeur goes and sits in the corner while the guy gives his lecture, and he’s done this maybe a hundred times by now, and the chauffeur comes to him one day and says, “It’s really boring just sitting there hearing this talk over and over but I’ve heard it so many times now, I can give this lecture. Why don’t you let me do it next time?” So they do. The physicist dresses up as a chauffeur; the chauffeur gives the lecture; it goes perfectly, but they forget that afterwards there are questions. The chairman of the department stands up and asks a question, and of course the chauffeur has no idea how to answer it, but he says, “I’m surprised that someone as eminent as yourself should ask such a simple question. That one is so trivial, my chauffeur can answer it.”

P. That’s a real classic. I love that story. It’s gotten me out of trouble lots of times.

S. Speaking of astrophysics, Timothy Ferris’s Coming of Age in the Milky Way is a real classic. I’m trying to remember if he has the inflationary universe in it. I think he does. But there are a few more recent surprises that of course wouldn’t be in there.

A.Always surprises!

S. This latest one is sort of unbelievable.

A. What’s that?

S. Well, you can work out the expansion rate of the universe by measuring the Hubble constant, as it’s called, of how fast things are receding, and from that you can trace everything back to when they were all in one place. So you can calculate the age of the universe from that measurement. We also have theories about stars. We can determine how old stars are by measurements we can make on them today. Well, it turns out that certain star clusters were older than the universe.

A. I read that. That’s a problem!

S. So there’s a big controversy.

A. The measurements were not perfect?

S. Well, everybody insisted “No, the measurements are right. Our calculations are right.”

P. The basic assumptions may be wrong. That there is a universe . . .

S.The way out of the problem was something nobody would have guessed. It turns out that the expansion of the universe is accelerating. Every theory would have said that it’s slowing down. You know, all these masses are pulling on each other. So they should expand more slowly as time goes by, but actually, the acceleration is getting faster. So, the Hubble constant that you measure now, when you extrapolate back, gives you an answer that’s too young, because it’s moving faster now. So that’s the big problem now. It solves the problem they had but it leaves another one.

A. What about an impossible explanation like this: that the expansion of the universe took place but it didn’t take place totally in a vacuum, or whatever; that there were in existence earlier star systems, that there were remnants, and that these remnants, through some means, whatever the specific law or logic would be, these remnants were there, you see, leftover, from a destruction of another previous universe.

S. Mmmm.

A. That’s not possible?

S. No, it’s almost certain that this universe came from another one.

P. Yes. So that this is the second universe or the twenty-third.

A. There had to be.

S. You know the history of astronomy is one of making men less and less important, less and less the center . . .

A. There’s not much further to go, because man is ...

[Laughter].

A. How far can you take this?

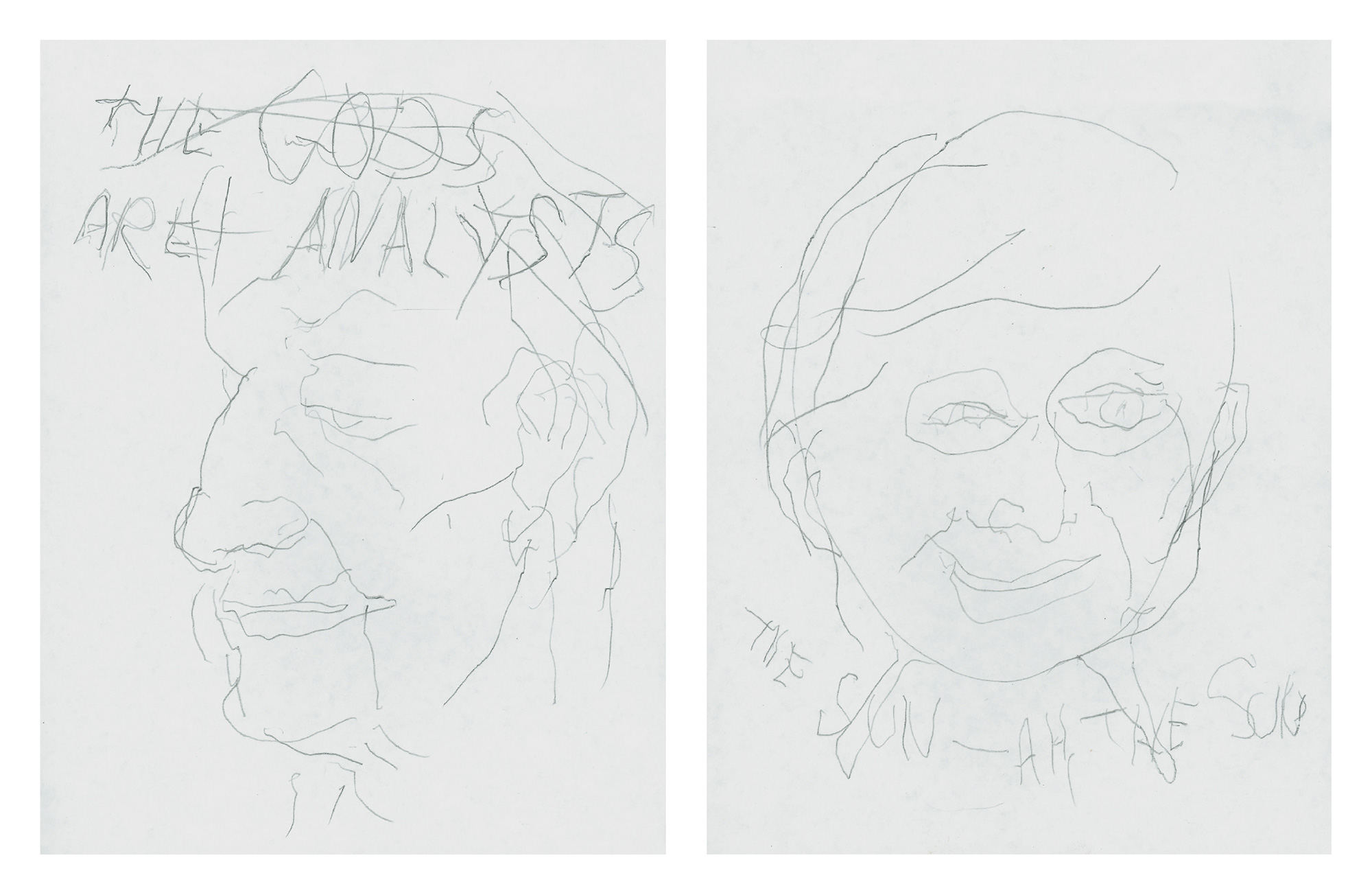

P. We analysts are like that. In fact, some of us really think we run the universe.

A. Well that’s because God is a psychoanalyst, it seems to me.

P. A psychoanalyst? No, he tried to be a psychoanalyst.

S. I always thought we got a trainee god who didn’t quite get it right.

A. A screwed up god. You know? Someone who is, in most respects, fucked up. But nevertheless, all of his results aren’t totally malignant, you know?

P. We expect too much.

A. Yep. The only thing that contradicts that is the perfection of our bodies.

P. How can you say that?

A. What?

P. How can you say the body’s so perfect?

A. Because the body is most amazing. Think of all the systems that are in your body. There are probably hundreds of different systems, coexisting, and maintaining equilibrium. And of course they break down or frequently start badly.

P. But...

A. It’s extraordinary how everything works. So on and so forth.

P. It’s not perfect.

A. Well, the body is perfect, but we don’t know how to live with our body, and we don’t know how to live in the environment.

P. But I would really question the perfection of the body.

A. Near perfection.

P. Yeah, but think about this for a minute. No environmental engineer would have designed the body in this way.

A. Is this being taped?

P. Yes. No environmental engineer would have designed the body this way. I mean, when you think about the fact that the waste disposal system runs right through the recreational area, that’s pretty stupid.

A. Not necessarily. It’s only because people have a moral attitude about the waste disposal system. If they didn’t have that kind of attitude and they just accepted that like anything else that was natural to the body.

P. It doesn’t go with recreation.

A. Why not? As a matter of fact, lots of people are specialists in that area, as far as recreation goes. I mean, there’s perfection and there’s perfection. There can’t be anything that’s absolute perfection. But the miracle, the extraordinary miracle to me, is how life could evolve from the early forms and we are still in the process of evolution, and we’re going to end up as this kind of half-machine, half-human. There was an article I clipped from the business pages of the New York Times, sometime in the early 1980s, in which it was talking about business opportunities for mixed organic/mechanical/technological kinds of creatures. They were already anticipating the kinds of profits that could be made once this had evolved.

P. Who would make the profits?

A. Capitalists.

P. The people or the robots?

A. Well, eventually the robots are going to take over. They’ll make that little jump into consciousness and say, “Why should we listen to these creatures who are less capable of functioning in the world than we are?”

S. I’ve had many long discussions about that, about what would it take for a computer, a robot, some mechanical thing, to develop consciousness.

A. It wouldn’t take much.

P. But then any good psychoanalyst would tell you that they’d all be conflicted, they’d all get depressed. They’d be immobilized.

A. But we know it’s going to happen because it’s happened once already. When our consciousness evolved. And the fact that it’s happened once means it can happen more than once.

P. Who says that?

A. I say that.

P. The real problem, as I see it, is that in the first fifty years of life, none of us runs into much trouble because natural selection operated in the first fifty years of life. Up until a few thousand years ago, very few people survived beyond fifty, and the second fifty years of life have not been subjected to natural selection. So we get all kinds of disorders.

A. Sometimes evolution develops because of an ecological niche, which opens up opportunities.

P. Serendipity.

A. Well, if you want to put it that way. I would prefer to say that conditions have shifted in such a way that evolution evolves! That the extension of life spans that has taken place since the early part of the twentieth century is just such a niche. That modern medicine, the development of prostheses, bioengineering, robotics, all manner of technologies, all show that there’s no limit that states that humans have to stay like humans have been. All sorts of variants can occur, and all sorts of species go out of existence, and new ones can arrive.

P. I don’t think so.

S. We have this discussion often. As far I can tell, species are replaced; they don’t actually evolve much.

A. Yes, but we’ve changed the conditions of evolution. It’s one thing when some marsupial faces an ecological problem, and it’s another when humans face a problem, given the resources that humans drag in to ensure their evolution.

P. They can also ensure their destruction.

[Later, over dinner].S. I should say how I first heard about Leon [the painter]. Because I was in grade school here in Brooklyn, PS 253. It must have been 1955 or 1956; I was in about third grade. And my teacher showed me a little notice in the New York Times about an art exhibit by Leon Golub and she said, “Is that you?” and I told her it wasn’t.

A. You should have said, “Not yet.”

S. I had already faced the canvas in the classroom, in third grade. I knew that that wasn’t ever going to be me. But I knew about the painter from the mid-1950s.

A. Pretty wild.

S. And then when I was a student at MIT in the late sixties, he had an exhibit there. There were posters all over campus with my name on them. My friends kept asking, “Is that you?,” So I felt entitled to take one of them off the wall. I have it in my office to this day. I went to the exhibit, and you and I spoke a bit. I thought about taking out my student ID card and showing it to you but then I thought, “Well, it’s just a name. This is really silly, you know, what’s the point?” So I didn’t say anything.

A. During the Vietnam War years, when I was active with a group called Artists and Writers in Protest Against the War, I met a woman who said to me, now I know both Leon Golubs. It was someone who knew you [points to the psychoanalyst].

P. I remember you told me that on the phone once, and I couldn’t figure out who it was. You said more than that. You said we dated, or had further relationships with the same women.

A. No, I didn’t say we dated.

P. That really puzzled me, you know.

A. No, I didn’t. I think you’re creating something which is not such a bad creation, but ...

P. It went on a bit, and I was really puzzled about it for weeks.

A. That’s how stories get disseminated. It’s almost astrological in a crazy sense, you know. The coincidence of our meeting each other, knowing each other, has to do with the curious providence of our names. It’s not that I looked you up for your writings on the sun, you know? Or you for the psychoanalyses you may have done...

P. Well, I’ve got mail and a whole lot of phone calls for you.

A. Once I got a letter, only once, a long time ago, and I forwarded it to you. And I think you once forwarded me a package or something.

P. I got phone calls about whether or not you were going to show up for an exhibit or something. I always said, yes, you would.

[Laughter].A. Well, if you get any more phone calls like that, you can say no.

P. I came to New York in 1950. I’d read about you then...

A. Such coincidences appear to be intriguing…

S. Huh. I came in 1949.

P. And I was a bachelor, and I was trying to, well I figured, I would get one of your paintings, hang it on the wall, because a lot of people and a lot of cute chicks were interested in paintings then. And if someone said to me, “Oh, you did a painting,” I would sort of shrug and you know, I wouldn’t lie, but I would just shrug. Then I looked at the paintings and by that time they were…

A. … and you changed your mind.

P. They were World War II scenes of things that would have destroyed me with women. You didn’t paint good stuff for me then.

A. Unfortunately, that’s the way it goes. A missed opportunity for both of us.

P. You could have changed my whole life.

A. I’m sure you did quite well with the ladies you met, despite the fact that you had no paintings of mine on the wall.

S. You put in your paintings all of the things that I try as hard as I can to ignore. Because I know people are awful. It’s so painful to think about it.

P. He rubs your face in it.

S. Yeah.

A. Well, we’re not going to solve the world’s problems tonight.

S.I think what we three have in common actually is that we all agree that people are screwed up and awful and clearly need help. Humanity is basically a mess.

A. As we said, they’re only good for the first fifty years. At the same time, we’re an amazingly successful species. Never been anything like it, you know.

P. It’s true.

A. And no member of any species, any species whatsoever, has ever been granted eternal life. But in our own realm we are pretty successful.

P. How are we being recorded? Is there a machine somewhere?

A. They’re just going to have to make up the whole conversation.

P. It would probably come out the same.

A. That would be okay with me. The way the three of us are going to end up is almost like we ourselves are figments of the imagination, created by the mastermind from Cabinet who wrote this fiction about the three Leon Golubs when there actually aren’t any Leon Golubs; or, if there are, they aren’t in the position to say the things that they’re saying.

P. This conversation’s going to slip into obscurity very quickly.

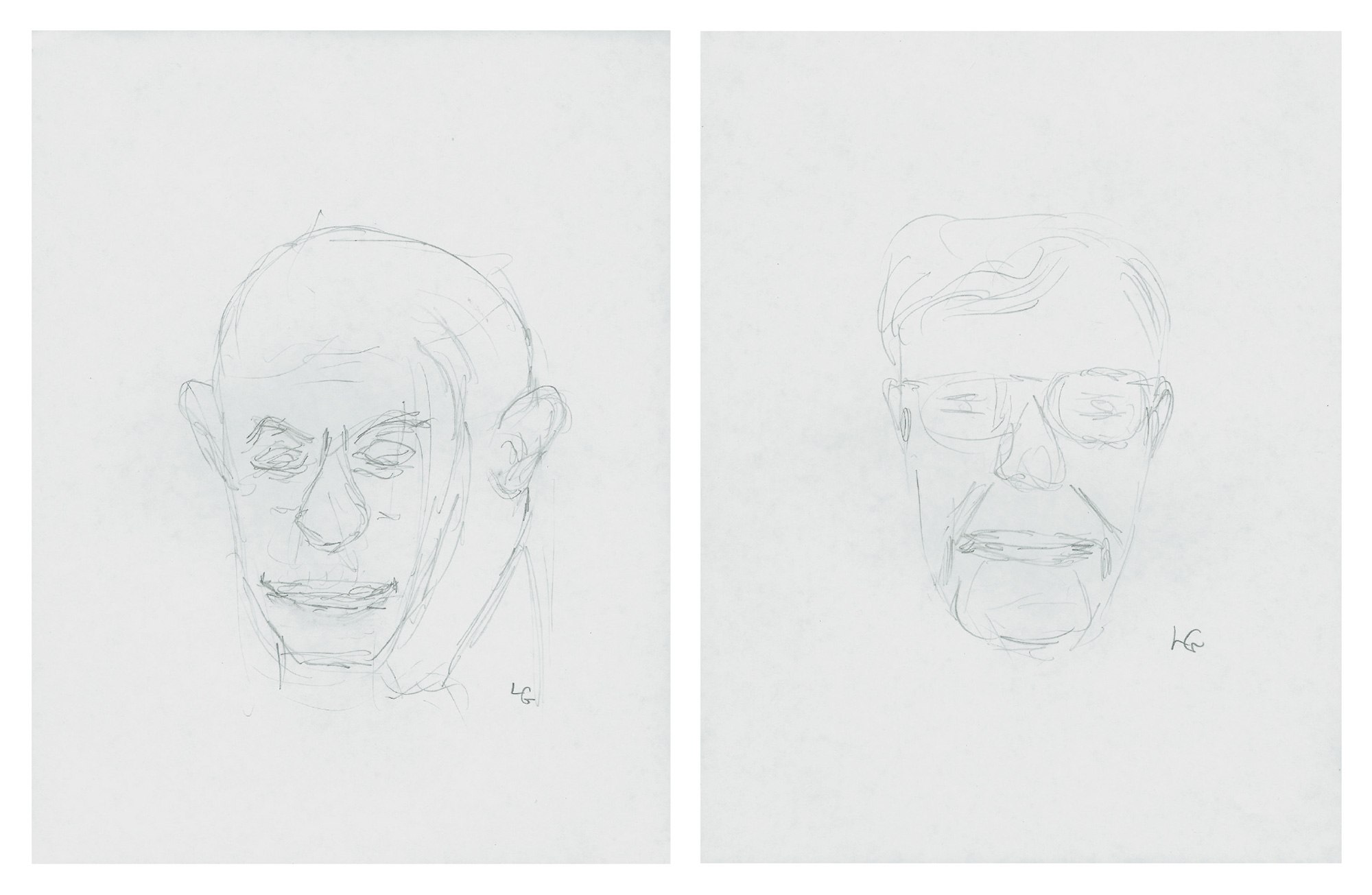

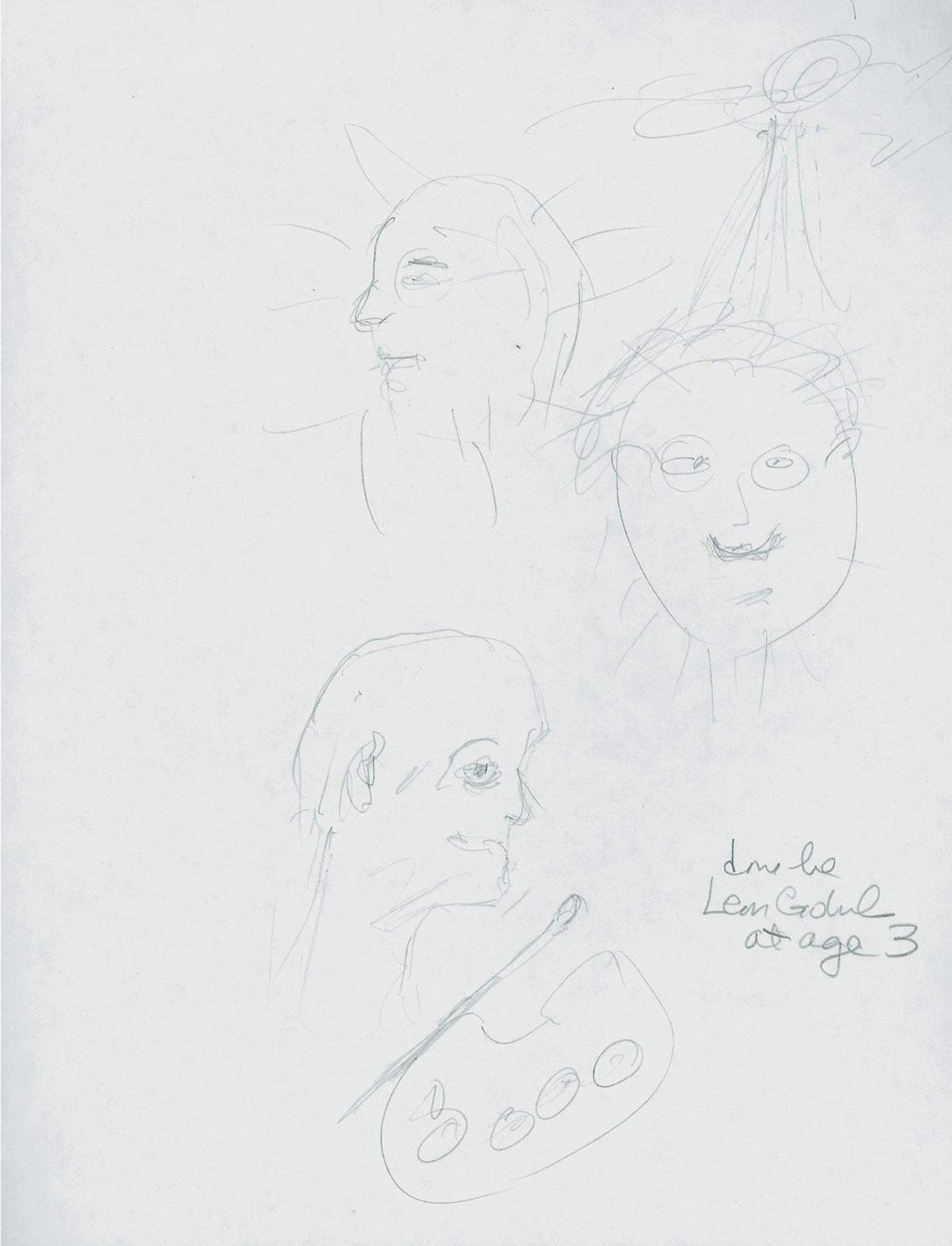

Leon Golub is an artist based in New York City. He has been exhibiting internationally since the 1950s in many exhibitions, including Documenta 3, Documenta 8, and Documenta 11.

Leon Golub is a psychoanalyst based in New York City.

Leon Golub is an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics and is the head of one of the teams working with NASA's Transition Region and Coronal Explorer (TRACE) spacecraft.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.