Be All That You Can Be: An Interview with Sandow Birk

A historian of the Great War of the Californias discusses its visual legacy

Marcia Tanner and Sandow Birk

Perhaps the most profound upheaval in recent California history, the bloody, cataclysmic, and ultimately inconclusive civil war between Los Angeles (Smog Town) and San Francisco (Fog Town) produced massive urban devastation, involved over three million Californians in combat—brother against sister, biker against surfer—and resulted in the deaths of more than 20,000 combatants. As a conflict almost wholly ignored by the mass media and the entertainment industry—even though they, along with other major corporations, helped sponsor both sides of the hostilities—the Great War of the Californias was virtually forgotten only months, actually only days, after it had ended, whenever that was. Its dates are uncertain, lost in a haze of mass hysterical amnesia over this traumatic collective memory, complicated by the compulsive viewing of reality shows on network TV.

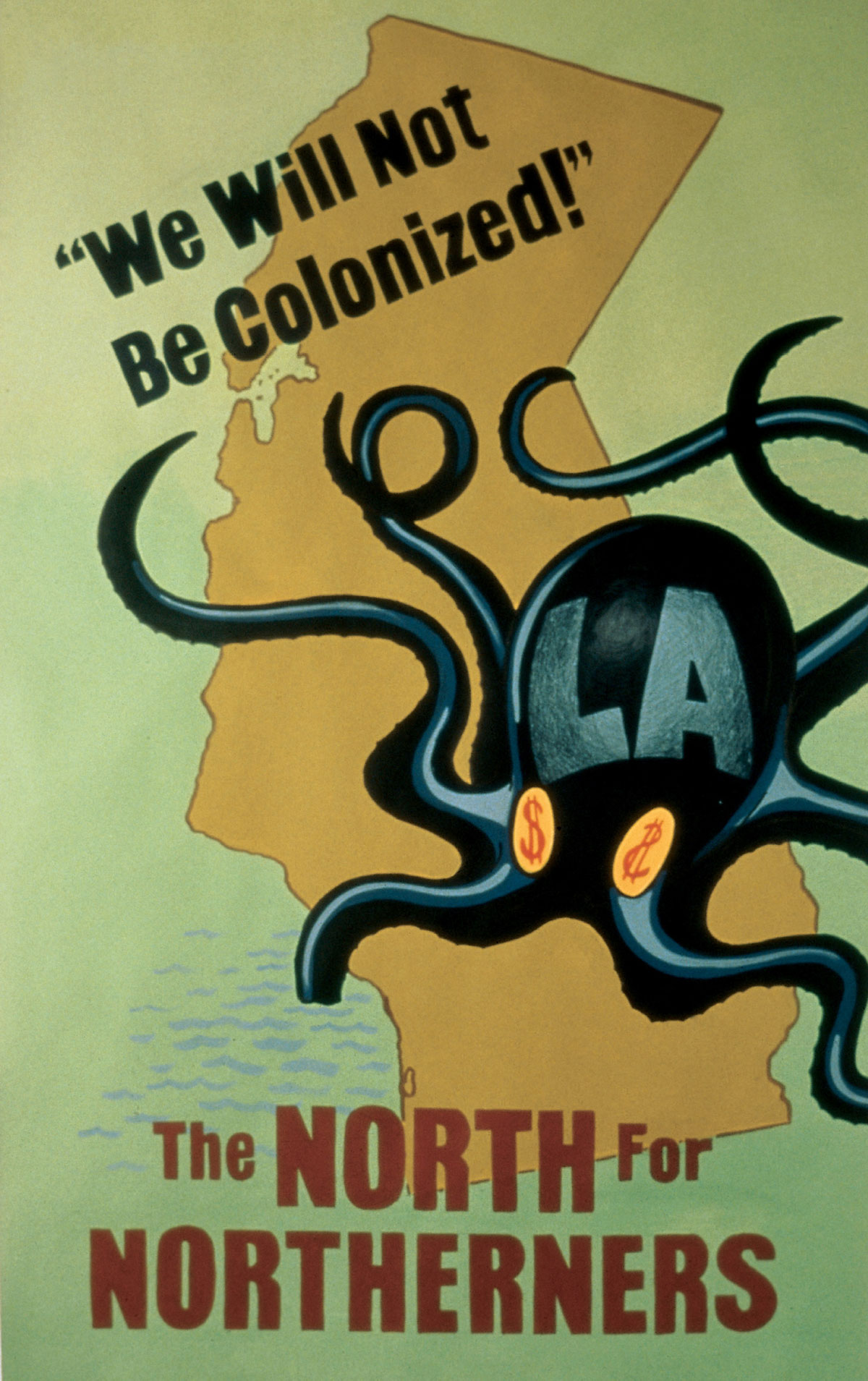

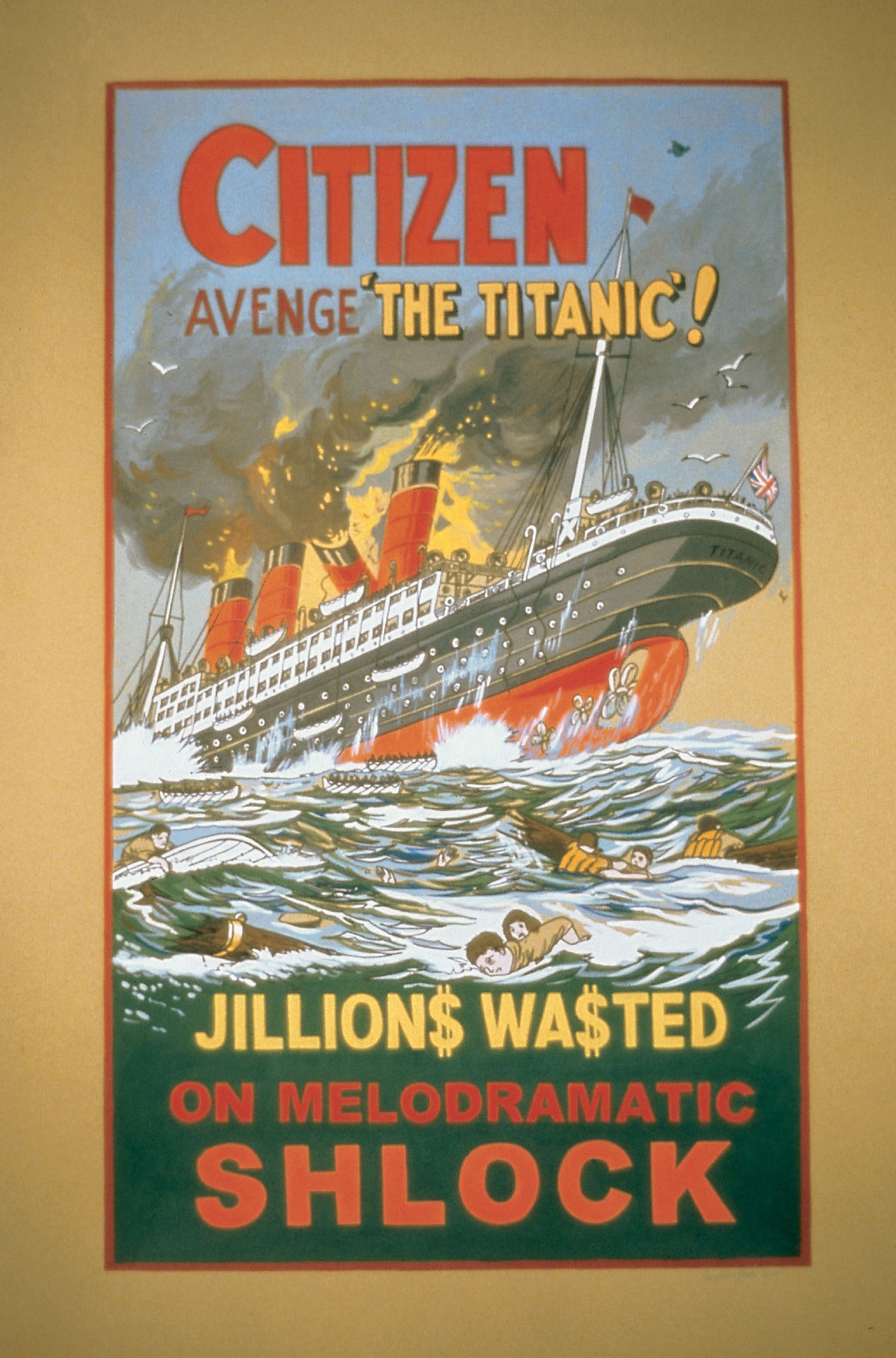

Fortunately for posterity, copious documentation of the Great War exists in the form of paintings, drawings, prints, and propaganda posters, as well as other artifacts. Although they commemorate and glorify wartime experiences from both Northern and Southern perspectives, these works by various hands bear an uncanny family resemblance—even as they heterogeneously, even maniacally, reference a wide array of disparate art historical models—that testifies to the unity of pan-Californian identity despite the state’s geographic, ethnic, class, and cultural diversity.

Tracing the deep kinship underlying this plurality of passionate cultural production and explicating these works’ relationship to the war have become Sandow Birk’s mission. A veteran of and eyewitness to the conflict, Birk is its chief chronicler and historian. His essay, “An Introduction to The Great War of the Californias,—from In Smog and Thunder: Historical Works from the Great War of the Californias” the catalogue to the landmark historical exhibition of the same title that Birk organized in 2000 at the Laguna Art Museum—is the definitive account to date of this tragic moment in California history.

A vicarious veteran of the war herself, Southern/Northern California hybrid Marcia Tanner exchanged emails with Birk and spoke with him on the phone.

Marcia Tanner: You were a Seaman First Class in the Artists’ Corps of the L.A. Navy. What was your role, if any, in documenting the war?

Sandow Birk: I was just finishing college when San Francisco fell to Angeleno troops. L.A. anticipated a counter-attack. I had drawn a low draft number so I knew that I would be called up soon. There was so much enthusiasm for the war at the time; it’s a little pathetic to think of it now, but everyone was so jingoistic and patriotic and I guess I got swept up with that. I went ahead and enlisted in the L.A. Navy so I wouldn’t end up in the Army or something. What no one really foresaw was that the next phase of the war would be a sea campaign and, ironically, by trying to avoid combat I signed myself right up for some of the worst of it. My first station was on the L.A.S. Tinsel Town and we saw some of the heaviest action off the Channel Islands.

As for the art thing, I had just finished studying ceramics and I guess they really needed people for the Corps because I got thrown into it even though my thing for years had been working on the wheel. I didn’t actually do much artwork during the war, although I did do what I thought was a pretty solid body of work using pinch pot techniques and bread dough.

If truth is the first casualty of war, what was the purpose of enlisting artists to work in this war? And why did they produce so much historical pastiche?

I never really understood the thinking of the top brass on why they wanted artists around, but as I do more research I’ve come to think that a large part of it was simple vanity on the part of General Gomez and his cronies. I think that the whole war was, to him, not only the peak of his career, but almost his divine destiny, as if he was a Mexican Napoleon, reuniting Aztlan by annexing Baja California and at the same time vanquishing both San Francisco’s old money families and the snobbish hordes of the Eastern establishment clinging to their overestimated cultural status in the Bay Area. A lot of his self-importance came from his Napoleonic view of himself and his powers. I think he saw the fine arts of painting and drawing as tools to convey the righteousness of his cause by tying his campaign stylistically to wars of the past.

How did your experience of the war influence your subsequent career? What inspired you to devote so much of your life to chronicling this terrible moment in California history, which many prefer to forget?

Well, basically because it’s so overlooked nowadays, especially with all of the recent saber rattling of George Bush II. It’s really a cliché, but you know each younger generation tends to think of the times they live in as being the most important and the most crucial in history, and to overlook the past and the lessons that can be learned from it. I guess I have that feeling, too. The War of the Californias was so devastating and formed so much of what we now understand of the Golden State, I want to do what I can to keep the memory of it alive, not only in honor of those who fought in it but because of the lessons that we can learn and carry forward. Not to mention that so much really great work was done by the artists involved, many of them at the beginning stages of their careers, and so much of that work is just languishing in self-storage lockers and garages from Marin to Mission Viejo. It’s really a tragic loss for the state, for the nation even, and I’m doing what I can to see that it’s not all forgotten.

What in your view is the lasting cultural significance of the war, and how is this reflected in and reinforced by the vast visual record left by artists of the period?

I’m sure the work would have a lot more influence if it could be seen by more people, but even so, it has had some influence. For example, on the most popular level, before the war a lot of the homemade do-it-yourself paintings you would find at garage sales used to be off-kilter flower paintings and distorted landscapes with the odd crying clown thrown in. But once the war and the whole patriotic thing had swept across the state, you saw a lot of self-taught artists doing some really wild stuff with abstraction and spin-art and some new directions in drawings made with Spirographs. Now, what that means in a larger art sense I’ll leave it to art critics to figure out, but I think it’s necessary to point it out and to try to keep some record of those kinds of changes. At the more official end of things, the rawness and the immediacy of some of the sketches done in actual battle situations are extremely powerful. There are hundreds of sketchbooks, portfolios, and cocktail napkins covered in these drawings and most are just rotting away in military storage right now. Not to mention the official, grandiose, over-the-top battle paintings that hang in board rooms, offices, and private homes that aren’t being seen by the larger audiences they deserve. They really are quite spectacular. Then there are the reams of posters, handbills, underground “comix,” limericks, etchings, and recipes that no one has even bothered to keep track of or to put together into a safe place where some serious study can be made of them all.

How do you account for the wealth of art made by hand (paintings, drawings, etchings, posters) and the total dearth of photo documentation?

I’m not really the one to ask about that because that is a whole different thing than what I’ve been working on. I can tell you that during the war and the months following, it was a really bleak, low time for ceramics in general and especially for work done on the wheel. What that means is that we have a really large gap in the development of vessels in that period and I could go on and on about that, about what that means for the ceramics community and what it might mean on a larger scale for the psychology of the population as a whole. But as for photographs, it’s hard to say. I mean, I’m sure there were, and are, tons of photos of all this stuff, from snapshots and official records to footage shot by the press, but for some reason it’s not really out there. It might be that it’s just too soon, too raw, too personal to so many people that by focusing more on the paintings and drawings, they might be sort of filtering their perceptions of it. I know that in the course of the research I’ve been doing, I have come across photographs, but, like you said, they don’t seem to be getting the attention the artworks do, even though the artworks are being overlooked as well. It’s an interesting phenomenon, isn’t it? It may be something as simple as that during desperate times people make do with what they have. Getting hold of film, developing the negatives, finding one-hour photo places, all of that was just too much, and maybe there were stacks of paper just sitting around.

You have written that many of the artists who depicted the war were unschooled, which is evident in the frequently clumsy draftsmanship, sketchy modeling, and sheer bad painting of some of the canvases, for instance. Others were clearly highly skilled and produced near masterpieces. But the artists remain anonymous. How do you explain this?

Well, that’s not really true. We actually do know quite a bit about many of the artists and some of them went on to long careers and large bodies of work. For instance, we know that Robert Tucker, who painted many of the most famous images of the war, such as the monumental Battle of Los Angeles hanging in Sacramento and the poignant San Francisco on the Ruins of Her City, went on to have a long career as a colorist in the animated television show SpongeBob SquarePants, which is a great example of how the fine arts can translate into a commercial venue and bring a lot of depth to the endeavor. We also know that careers went the other way, too. For example, Stephen Housely, whose brilliant painting of the assassination of Governor Pete Wilson won him so much praise when it was first exhibited, was never able to equal that success and ended up struggling for years in a loft in downtown L.A., ever hopeful of a “downtown revival,” until he ended up dead of an overdose—just when the whole Chinatown scene was kicking in. An “overdose of self-pity,” one critic called it. And there are numerous instances of artists who carried on in the arts and did very well for themselves, forming garage bands, opening piercing parlors, painting backdrops for the movie industry, developing websites, and on and on. Again, it’s not so much that they were or even wanted to be anonymous—it is just that they have been overlooked. All that information is out there; it just hasn’t been properly documented and gathered and saved, and that’s what I’m really concerned with.

The propaganda posters represent perhaps the strongest body of work the war has left behind, and demonstrate vastly different approaches in technique, style, and design. They graphically reveal and reinforce the savagery and depth of the rivalries between North and South, while serving effectively to inflame them even further—although some, like Avenge “The Titanic”!, could appeal to either side. Did the Hollywood propaganda machine give Smog Town’s poster campaign an edge?

Again, I have to disagree a bit with you there. There are actually several disciplines that produced amazingly powerful bodies of work either directly about the war or because of its profound influences. It’s just that the propaganda posters were so ubiquitous that they seem to have remained more in the public memory than other bodies of work. I mean, scholars can tell you that the whole field of macramé was profoundly affected, profoundly altered, by the war and by advances in materials brought on by military research at the time. Not to mention the carving of driftwood into incredibly lifelike sculptures of sea life, an art form that really took off in new directions almost wholly as a result of the influence of the war. I could go on. But, yes, the propaganda posters are some of the most compelling images that have survived and they are quite diverse. That was simply because of the wide variety of artists working in the medium, the range of artists employed by the Corps. And yes, I think you might say that Hollywood’s experience with reaching “the masses,” the faceless, consuming hordes, gave it the edge in propaganda. After all, they had entire squads of poster makers and image spin artists already employed, who were very familiar with what worked and didn’t work when it came to catching the attention of a multicultural audience and communicating with it in bold, clear images. The North, too, made quite an effort to use the poster as a propaganda tool, but I don’t think its efforts were as successful. Let’s face it, coffee house poetry readings and glossy homosexual erotic publications have a much harder time catching the public’s imagination than, say, the work of a team capable of producing a masterpiece like Get Shorty.

I’ve heard that the posters were designed and executed by convicts incarcerated in California prisons. What was the rationale?

Yes, that is true, and it’s sort of an aside. What happened was simply that the military establishment needed more soldiers, meaning that they needed young men. Now, adolescent and college age males are generally at a stage in life when old established ethics and morals are being discarded and rebelled against, rather than embraced. Here you have the dilemma: how do old institutions sell themselves to the young and rebellious? Or rather, how does the Army become “cool”? Well, they follow the Mountain Dew example. They see what “cool” is and they use it to represent themselves. So you see the army looking to alternative imagery, and identifying graffiti and gangster chic and hip-hop as potential means to seduce an ambivalent youth culture into an unpopular war. Then they go looking for the best and brightest of the graffiti world and find many of them locked up. Too bad? No, better! Now you have a captive workforce and low production costs! Perfect fit.

Historians have raised doubts about the veracity of your accounts of the Great War. Some, like the revisionists who deny the Holocaust ever happened, claim that the whole thing is a hoax: the product of the fevered imaginings and paranoid fantasies of an outsider artist maddened by the inequities and absurd anomalies of life in contemporary California and, by extension, the United States. How do you respond to them?

Well, that’s a whole other topic. Mike Davis has looked over everything of mine and he doesn’t see anything wrong with it, so ... What we really need is not a bunch of naysayers nitpicking at details, but a concerted and organized effort to preserve some of these artworks, treasures, really, before it’s too late. Especially now, with the whole country so preoccupied with the prospect of yet another war, it’s an especially important time to save what we can from past wars and to learn from our own history. I think any intelligent person can tell you that, and the bickering of a few vocal skeptics out there seems to be coming from the high towers of academia rather than from hands-on, hunter-gatherer historians like myself. I say let’s get off our high horses and do this thing now, before it’s too late, rather than trying to shoot the legs out from people doing the best they can with modest resources.

Sandow Birk is an artist who lives and surfs in Los Angeles. His most recent project is a rewriting and illustrating of Dante’s Inferno set in contemporary urban America. He is represented by Debs & Co. Gallery in New York, Catharine Clark Gallery in San Francisco, and Koplin Del Rio in Los Angeles.

Marcia Tanner is a Bay Area-based independent curator and writer. Her writings on art have appeared in Art+Text, Artweek, LIMN Magazine, VISIONS Quarterly, ArtNews, the San Francisco Chronicle, and other publications. She is a visual art curator at New Langton Arts in San Francisco.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.