Looking Down

The God’s-eye view of the aerial photograph

Albert Mobilio

Two photos taken any length of time apart, when paired together, will tell a familiar story: Before and After. A photo of an altar boy at 8 years of age set next to the police mug shot of the same boy at 28 tells a readily apprehensible if not shopworn tale. The photo of a grocery storefront on the Lower East Side in 1910 forms the first half of a sociological narrative whose second half proceeds from an image of the same building now occupied by a sex toy shop.

It is the nature of aerial photography—because of its ability to encompass much from a seemingly omniscient perspective—to tell epic tales. The term epic is used here to describe stories that elide the role of individuals in favor of the action of large, impersonal forces. The paired images of the altar boy and the criminal evoke an arc of narrative time that is nuanced with the particularity of a single life: they form a biography, autobiography, or a novel. The contrasting photos of the storefront certainly tell a less immediately personal tale, but one still marked by the activities of an identifiable community—striving old world immigrants replaced a generation later by their unfettered, decidedly new world children. Such storylines offer up figures who—in the manner of modern protagonists—encounter complications, struggle, and reach some sort of resolution. On the other hand, the vastly generalized information available from the “god’s eye” view—think of the famous photo of Earth as seen from the moon’s surface—is too diffuse, too resistant to comprehension to be compared to narrative forms that focus on the modern notion of individual fate. To find a narrative analogue for before-and-after aerial photography we might look back to the epic tale—say, Homer’s Iliad or Virgil’s Aeneid —with its huge cast of characters, myriad subplots, and irrational gods. In these narratives the intention and agency of any one individual is subsumed within the bigger, Olympian picture—the eternal contest between creation and destruction.

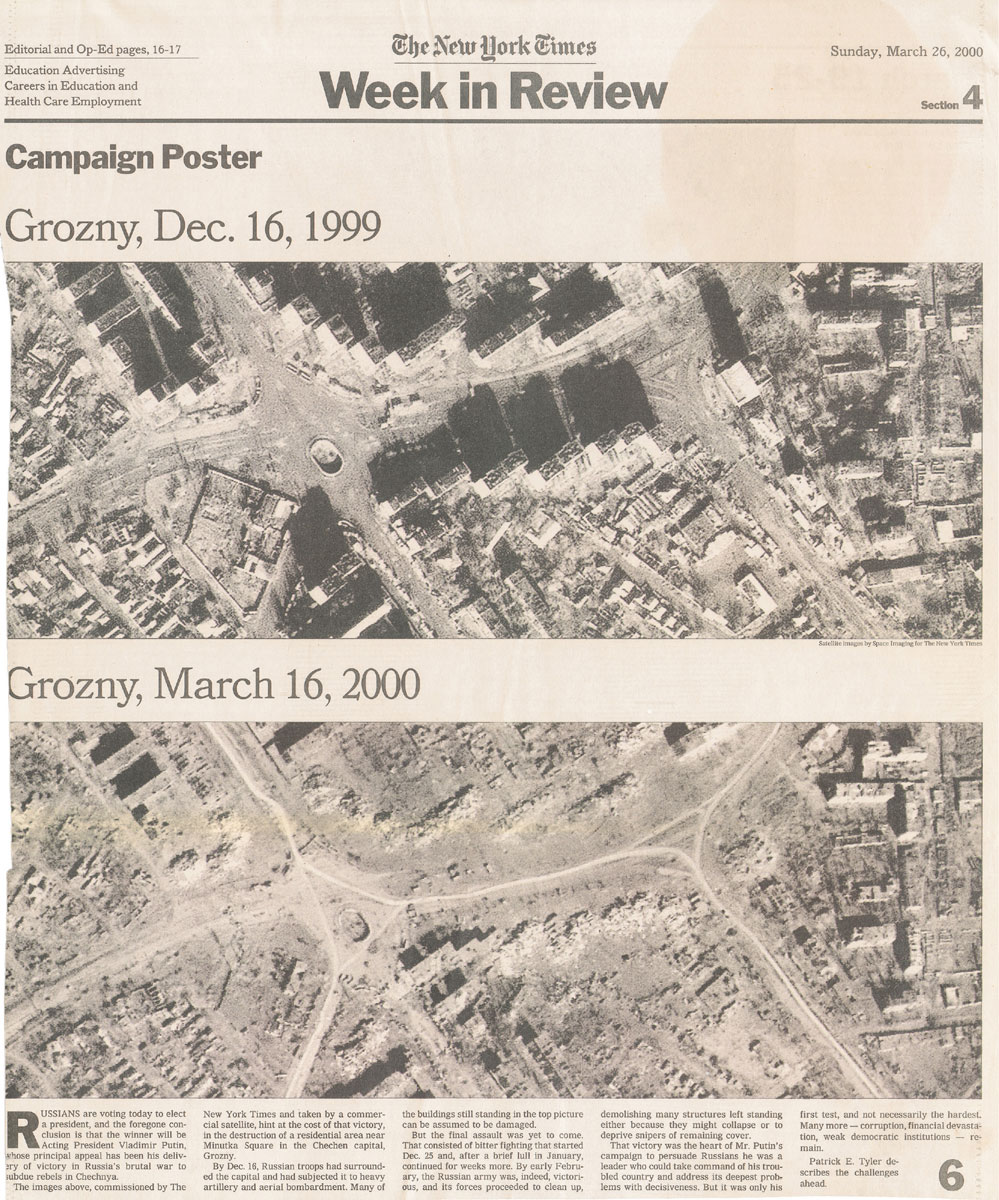

In the New York Times on 26 March 2000, the entire front page of the “Week in Review” section was taken up with two large aerial photos; they were titled “Grozny, December 16, 1999” and “Grozny, March 16, 2000.” The caption provided the relevant context: On 16 December, Russian troops had surrounded the Chechen capital of Grozny and subjected it to “heavy artillery and aerial bombardment.” By early February, the Russians had invaded the city and demolished many of the buildings left standing. The comparison between the two photos, taken about 90 days apart, is said by the Times to “hint at the cost of that victory.”

When I first saw these pictures I knew very little about the war in Chechnya. I know very little now. Nonetheless, I was fascinated by this pair of contrasting images, even though they provided me with no real information about, for instance, Chechen-Russian history, the role of religion and ethnicity in the region, the nature of the conflict, the combatants, the casualties; indeed, nothing tangible about the labyrinthine reality at which these two photos could merely “hint.” But this hint was a suggestive one. While it did not include any stories of individual struggle and loss—the stories I’d been avoiding in magazines and newspapers because I was just not ready to bone up on another conflict, another history, another tale of irreconcilable enmity—it did impress upon me the existence of powerful, recurring, and impersonal forces in the world. And this proved reassuring. Reassuring because such forces appear irresistible and ultimately unfathomable. They absolve us of the need to absorb particulars; to bear witness. To view the world principally as an arena in which these forces contend is to view life in a way that approximates the perspective of the divine. In the case of Grozny, the forces at work—the urge to settle and build a city, as well as the equally persistent need to destroy that same city—had been cleanly stripped of their human particularity by sheer altitude. I was looking down with a kind of imperturbable clarity, the unknowing knowledge of Homer’s gods who never quite figure out what motivates the humans whose destinies they control.

The December photograph shows a residential area near Minutka Square. At the center of the frame a dozen huge Socialist-style housing high-rises are arrayed inelegantly around a large traffic intersection. The massive buildings cast even larger shadows toward the upper edge of the image. In the March photograph, nearly all these buildings have been reduced to rubble. Unlike the photos of Dresden in the aftermath of its firebombing, the buildings are not charred skeletons; they have been pummeled into what could be said to resemble Native American burial mounds. The shadows are gone and everything is brightly lit; the sun has been permitted to find its way into every basement and alley. Before the bombing, there is a raised ellipse set in the middle of the intersection, which is, perhaps, some kind of public monument. This too has been flattened, yet still it remains the most recognizable shape to survive from December. The broad avenues have been thickened with debris and single-lane paths have been carved out, no doubt by Russian military equipment. It looks as if sheep paths that existed millennia ago have been resurrected out of the fallen city’s dust. The lines call to mind another image of Native peoples, the Nazca Indians who left complex geometric images—visible only from a height they could never have attained—on the plains of Peru. The wiry geometry that has taken the place of streets in Grozny is available to a god’s eyes as well, not to mention those with access to satellite imagery. I look down and know nothing of the lives there. Except that this is what people do; they build and they destroy.

In the book Above Los Angeles, which features photographs taken by aerial photographer Robert Cameron, an image of Playa del Rey, circa 1925, has been juxtaposed with one of Cameron’s shots of the same locale taken in the late 1980s. Over the approximately 55 years that separate the photos, much has changed. The Before and After would seem to be a straightforward tale of urban development. Although the basic landscape of a flat plain demarcated by steep cliffs, a beach, and ocean remains the same, the plain that was open and empty in 1925 is still so but now purposefully—it is Los Angeles International Airport. The cliffs are studded with homes that cantilever out over the sand below. And the beach, too, has been broadened by the addition of groins. The roads that tracked the coastline and curved up into the cliffs are still in use, as are the bridges crossing a narrow inlet from the sea. Even a few buildings have survived Los Angeles’s accelerated cycles of development and demolition. Mostly, though, there are many, many more structures. No more than two dozen buildings can be located in the 1925 photograph; several decades later they are too numerous to count. By the 1980s, the incline of the cliffs has been softened, well-tended grass has replaced the scrub brush, and even the ocean appears to be more carefully groomed.

This swath of arid coastline has been built over and populated, the reverse of the process evidenced in the Grozny photographs. At Playa del Rey, the timeline extends more than half a century; in Grozny, barely three months. Yet for all the apparent rationality of Playa del Rey’s before-and-after narrative—the ocean is beautiful, no wonder so many people wish to live close by; the land is flat, of course you would want to land airplanes there; the beach is commodious and inviting, why not make it wider. There is, from this airborne perspective, something as inexplicable as the story the Grozny photographs tell. At this remove, these intricate human motives can only be inferred; they are no more legible than the many causes behind the flattening of a neighborhood in faraway Chechnya. While I know much more about what has actually happened in LA and why it has happened, the Olympian character of these two images undoes this knowledge. True, I know about Americans, our love of our cars, our real estate deals, our fondness for bright green lawns, for baseball fields, for convenient access to everything and everywhere, our appetite for advantage, our disinclination to leave anything—the ocean, the sky above LA—alone. If I understand all of these factors to be inextricably webbed, I also understand their individual strands with felt specificity. Still, this pair of images does not conjure individuals, their choices, desires, or, for me, the moral judgments that might attend upon such actions. Instead, it offers assurance from on high: This is what people do; they build and they destroy. Seen from a bird’s path or a god’s perch, the human enterprise is so large as to be very small. So detailed as to be exceedingly simple. The aerial view: it provides a peace that passeth understanding.

Albert Mobilio is a poet and critic based in New York City. He is the recipient of a Whiting Writers’ Award and the 1998 National Book Critics Circle award for reviewing. A book of fiction, The Handbook of Phrenology, is forthcoming from Black Square Books. He teaches writing at New York University and is the fiction editor at Bookforum.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.