Artist Project / Taliban

The intimate enemy

Thomas Dworzak

In contrast to other recent conflicts, the photographic record of the US military operations against the Taliban in Afghanistan in the autumn of 2001 seems relatively scant. The swiftness of the campaign, the often exceptionally remote locations in which it was conducted, and the ultimate elusiveness of the enemy seemed to generate fewer conventionally illustrative photo-ops than usual. Indeed, many of the most memorable pictures to emerge from the recent war in Afghanistan arguably came not from professional journalists covering the conflict, but instead from what were essentially found photos, often produced under the auspices of their own subjects. These images—think of the grainy screen grabs of Osama bin Laden’s video messages or the frequently circulated fuzzy file photo (supposedly one of only three in existence) allegedly depicting Taliban leader Mullah Omar Mohammad with his face partially obscured by a white turban and a gray hood—only emphasized the formlessness of this particular set of enemies, functioning as symbolically loaded, self-created stand-ins for individuals whose bodily presence evaded Western lenses, just as they evaded the pursuing troops.

In the same way one might expect a profusion of images around the worldly master propagandist bin Laden, the photographic obscurity of Mullah Omar (and his followers) also makes perfect sense, particularly given the cultural context from which the Taliban emerged. Raised in the mud-brick huts of Singesar, a small village just outside the provincial capital of Kandahar, the 45-year-old Omar, a veteran of the guerrilla war against the Soviets, built Afghanistan into the world’s strictest Islamic regime—one where, in keeping with literalist interpretations of Koranic injunctions against idolatry, representational depictions of living things, and particularly humans, were expressly forbidden. From the mid-1990s onward, essentially all such photography in Taliban-controlled Afghanistan was banned, notes Thomas Dworzak, a Magnum photographer who worked in the country during 2001 and 2002. The only exceptions were a select few studios that were allowed to operate in order to produce identification photographs for government documents and passports.

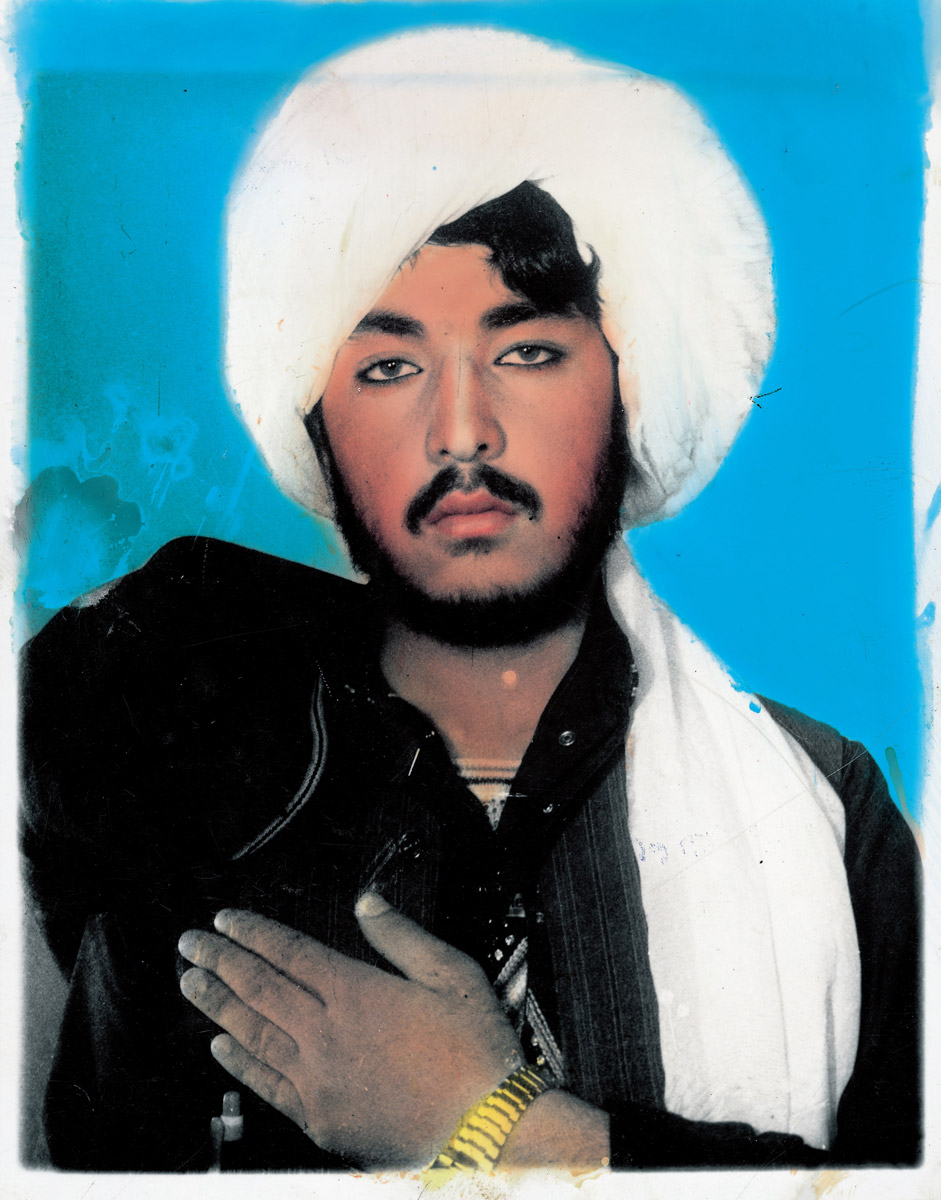

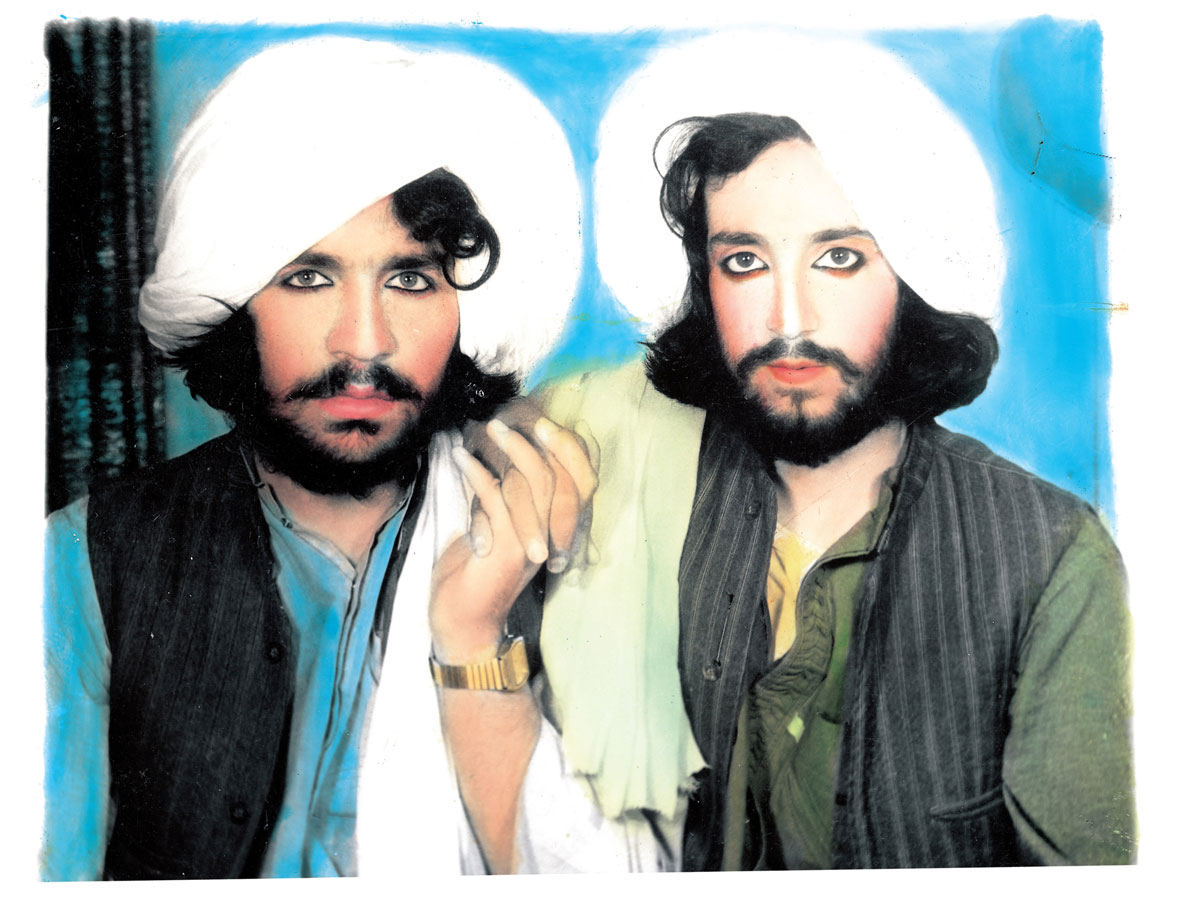

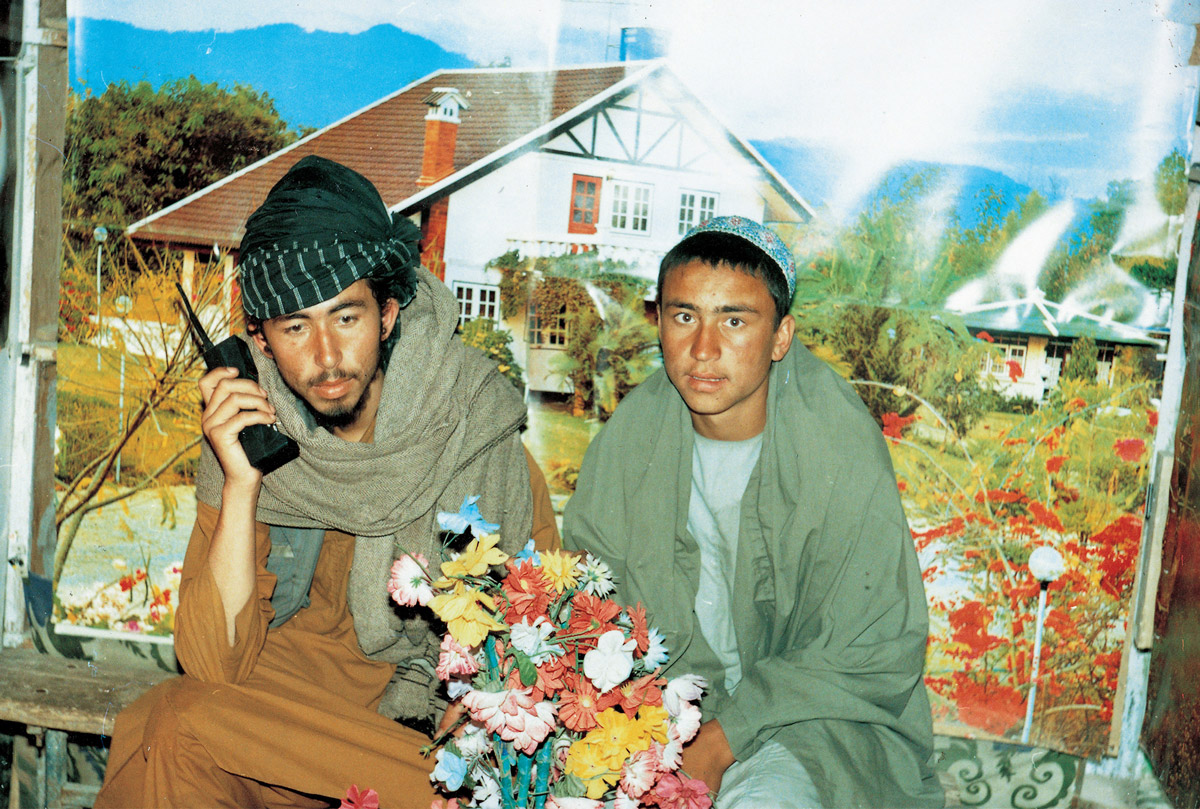

The photos presented here represent a selection recovered by Dworzak after the war from such studios in downtown Kandahar, the center of Taliban power. According to him, the photographers working there had a busy clandestine business producing these flamboyant portraits for the Taliban fighters who had come in to sit for their official ID pictures. As journalist Jon Lee Anderson notes in his introduction to Taliban, a book published by Trolley Press featuring a selection of the images, the members of the Pashtun tribe (to which Mullah Omar belonged) and particularly those in the Kandahar area, are known for their surprisingly showy personal appearances; often sporting dyed hair and beards, favoring colorfully ornamented heeled sandals, decorating their fingernails and toenails with henna, and outlining their eyes in dark kohl. The images brought out of Kandahar by Dworzak—featuring men alone and in playful, sometimes affectionate groups, treated with romantic flourishes of florid hand-coloration or simply posed before cheerful Alpine backdrops with feminizing floral accessories—produce an extraordinarily intimate and utterly counterintuitive portrait of an enemy that even two years later has remained largely invisible to Western eyes.

According to Dworzak, none of the portrait photographers “seemed to think that the pictures were either contradictory or hypocritical of the Taliban, nor as dissident or of any particular value… As there was little chance that the Taliban would return to collect the photographs, the studios were happy to sell them.” As one of the photo studio owners told Dworzak, “Most of them are dead anyway.”

Thomas Dworzak is a Magnum photographer whose work has appeared in publication including The New Yorker, Newsweek, and Paris Match.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.