Talking to My Old Science Teacher about Drawings in which I Killed Him

Business Reply Mail abuse, beard theory, and makeshift gallows

Brian McMullen and Mr. Hawkins

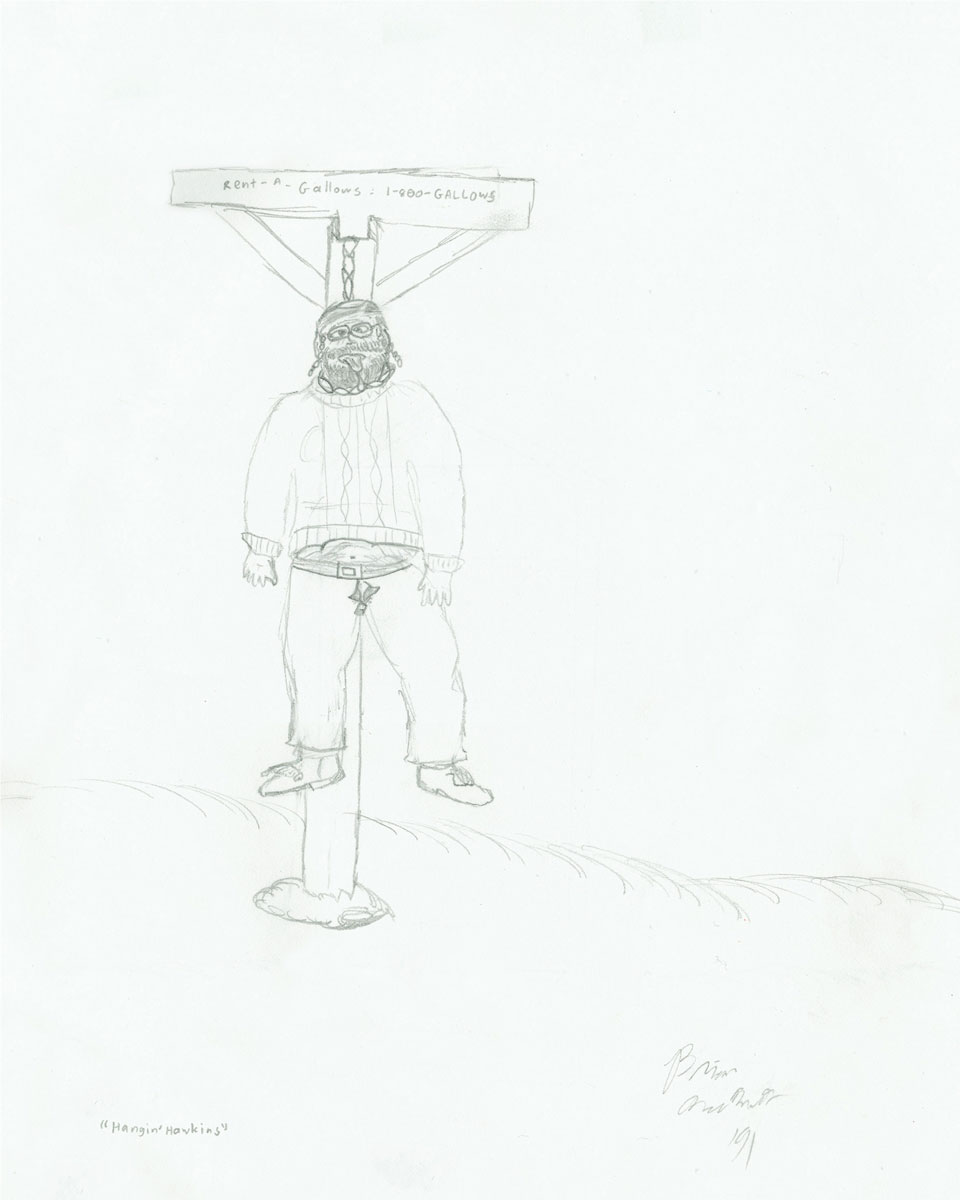

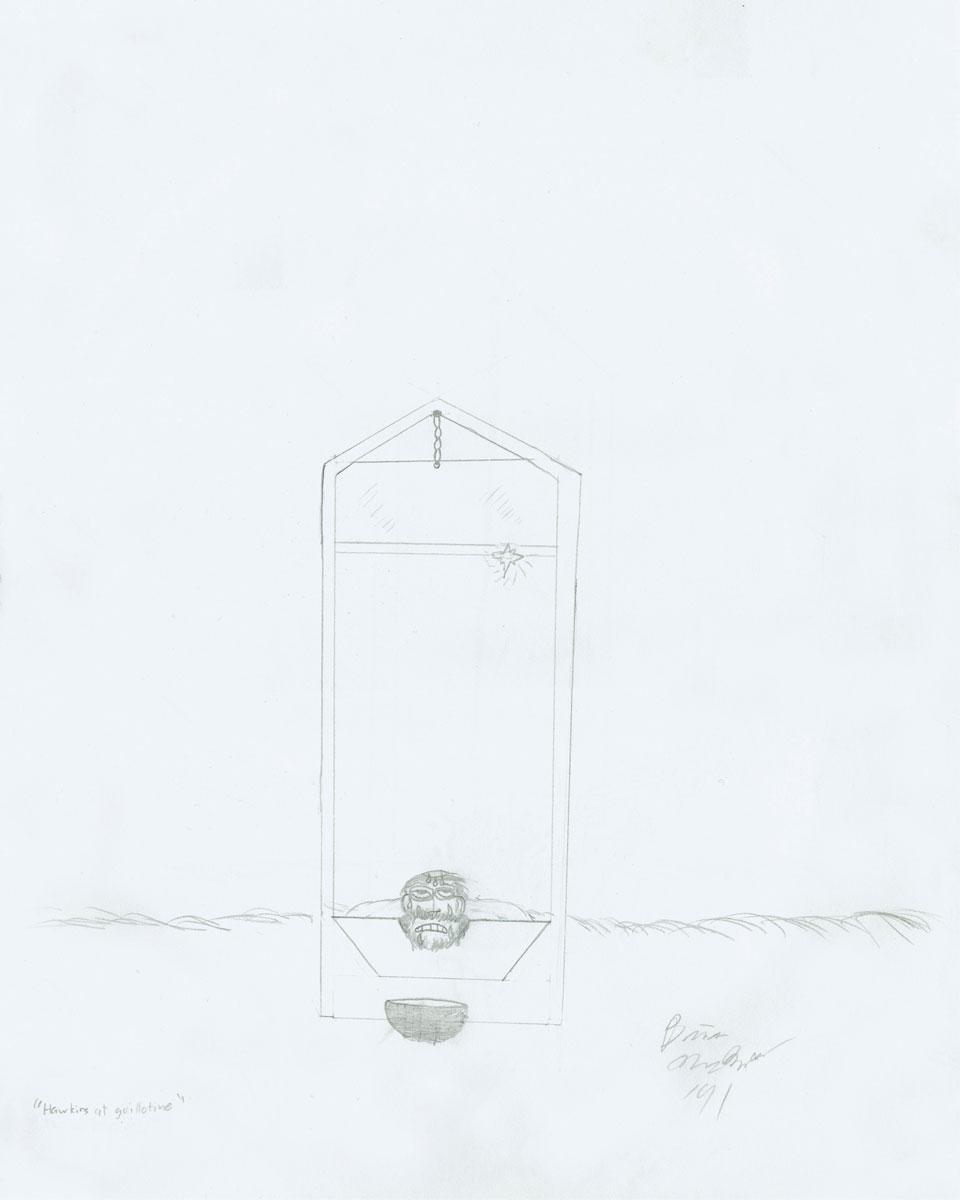

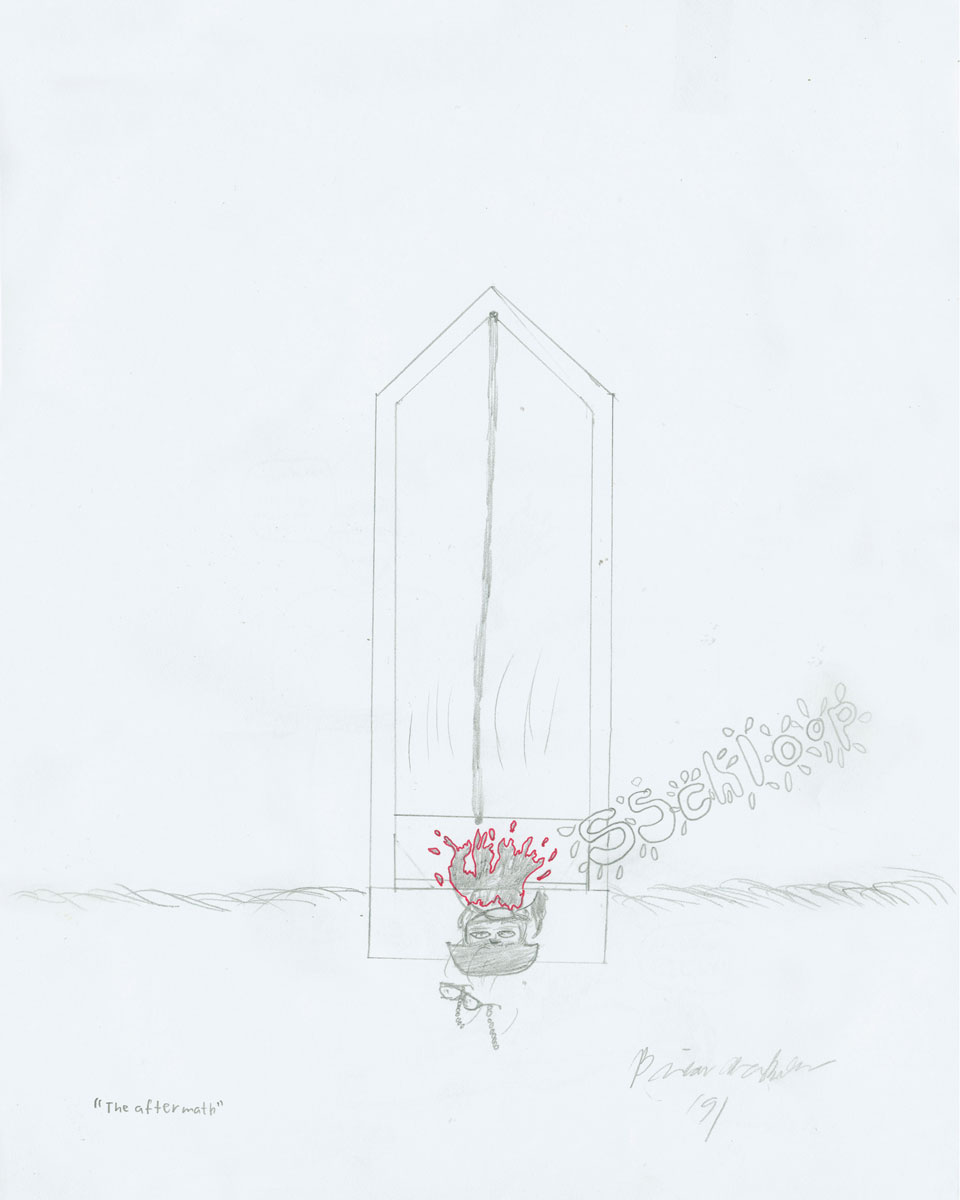

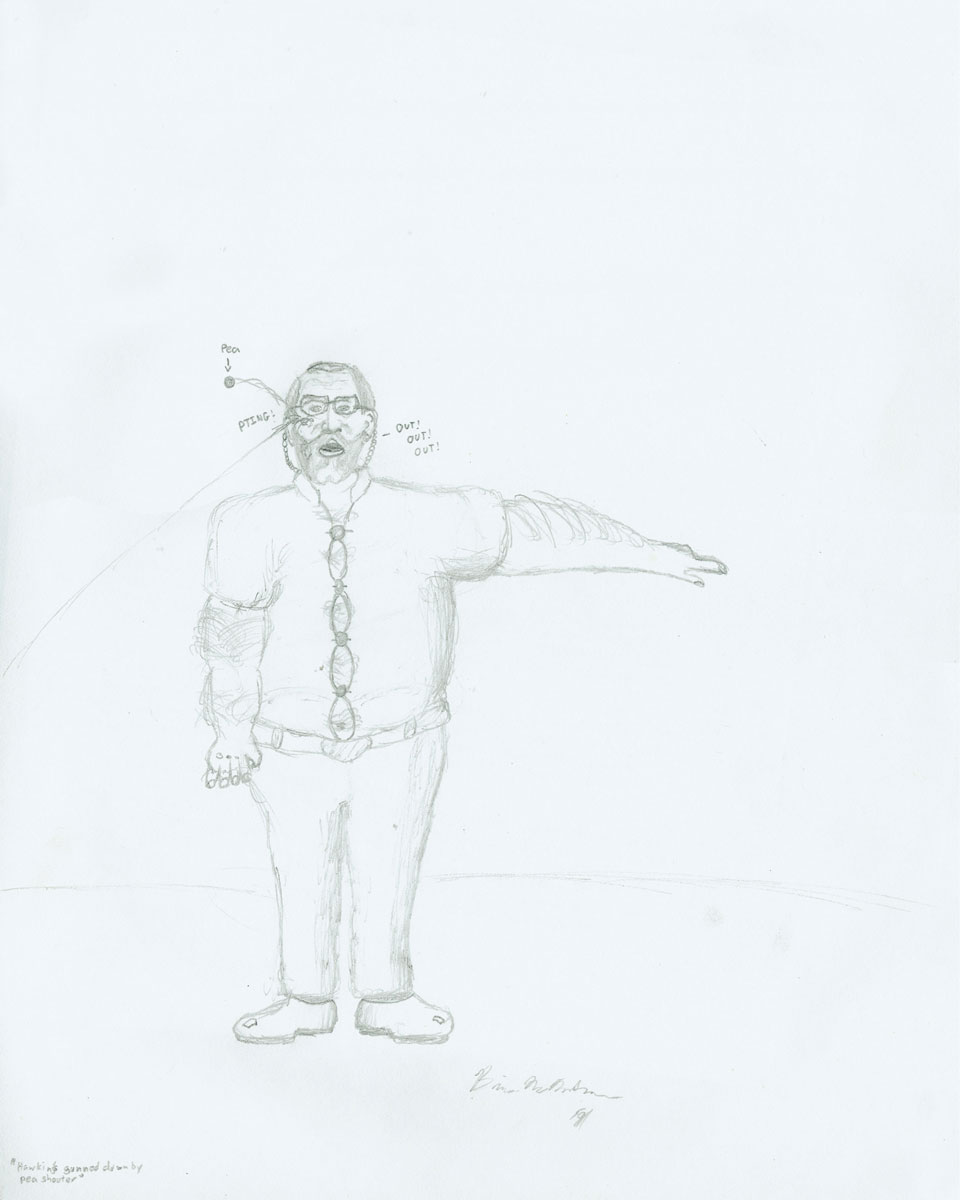

Half my life ago, as a fifth grader at Maumee Valley Country Day School in Toledo, Ohio, I began to draw a lot. I would go to my oversize, Christmas-present sketchbook on weekday afternoons, when the Nintendo was off-limits, and fill it mostly with made-up stuff: new comic book characters and sketches for video game sequels. One afternoon, though, I decided to draw a picture of my science teacher, Mr. Hawkins, hanged at the gallows. I liked drawing that picture. I liked adding the details: the drooling tongue, the unzipped fly, the “1-800-GALLOWS” service mark. In four more after-school drawings, I brought new kinds of secret justice to the mean Mr. Hawkins: a guillotine, a meat cleaver, and a pea shooter. (With the pea shooter drawing, the excitement faded.)

For the “Enemy” issue, I thought I’d try to find Mr. Hawkins, show him the secret drawings, and ask to have a telephone conversation. This actually worked. Mr. Hawkins, who is now retired, was kind enough to talk with me for three-and-a-half hours. Here are some excerpts from the conversation.

My first question is—you’ve seen the drawings now. Do you have any questions?

Oh, I don’t think so. They’re pretty straightforward.

Okay.

Over the years, there were lots of talented artists who did this sort of thing. Was there a Franklin[1] contemporary with you?

Yeah, Matt Franklin. Did you catch him with drawings of you?

Well, no, but his younger brother did this sort of thing. I don’t know if he drew me, but he drew these kinds of pictures. He was a really fabulous artist for that age. I mean, I would have to say better than you in his ability to depict reality.

Okay.

But he was into heavy metal and all kinds of stuff, so a lot of his drawings were pretty gory and pretty violent.

Were they secret?

Well, some were and some weren’t. Every kid in the entire UI[2] knew he was an artist. He would illustrate his projects and also just draw pictures, for the fun of it, that were fairly dramatic. I never saw him do anything like this, but he and I had a very rocky relationship, so it wouldn’t surprise me at all if somewhere in his stuff are pictures a lot like these.

I see.

But you know, I don’t remember you and I having any particularly difficult times.

Well, outside my mind I don’t think we did. I liked approval, I hated to get caught, and I hated the thought of having my name written on the board.

Uh-huh.

In fifth grade I remember thinking—in a big, vague way, you know—that you were mean. Before I decided to send you these drawings, I tried to come up with a list of reasons why I thought you were mean. First on the list is your gruff voice. And your directness. You’re not a coddler, as I recall.

Yes. Very true. The only kids I would coddle were the ones I’d identified as having some sort of emotional problem.

I remember you were the first teacher I heard swear.

Yeah, probably.

I was around the corner, in Mrs. Burke’s room, playing a word game. Suddenly, your chalk tray—the big, five-foot-long, magnetic one—fell off the board. The sound was unmistakable. In reaction, you said dammit. The word grumbled out of you like—and I had this analogy pre-prepared—like a warning groan from a dormant volcano. It was low and soft and everywhere. I was scared. You scared me.

Hmmm.

There was also this time when you gathered up everyone’s Nintendo Game Boys into a black Hefty bag before we got off the bus for Camp Joy. You were the Grim Reaper.

At the time, did you understand why we did that?

Well, yeah. The integrity of the trip—it was the Joy Outdoor Education trip…

Right.

The Game Boys would have completely compromised the point of the trip. A bunch of kids staring into screens would have killed, or seriously hurt, the group bonding that was supposed to happen.

And we didn’t explain that to you?

Well, I’m sure you did. But there’s hearing the explanation and then there’s giving up the fragile, favorite toy.

The team of teachers, probably long before you guys, had made decisions about how to handle situations like this, the collection of distracting materials like Game Boys.

But you were the guy holding the Hefty bag.

Yeah, right. And there would have been somebody else on the other bus with another Hefty bag.

I hid my Game Boy from you.

[laughs] Really?

I thought it would get scratched or broken. You plus garbage bag equaled problem. But I didn’t use the Game Boy the whole trip. I was afraid you’d catch me. You seemed to have eyes everywhere. A dormant volcano grim reaper with eyes everywhere.

That was a myth we encouraged.

• • •

Another and I think really important thing that helped me think you were mean was the beard. The neat, full, black-and-white beard. Do you still have the beard?

Oh yeah.

You were my only bearded teacher until high school. I have this theory that the beard was a key part of your authority.

Really?

Yeah. Remember the P. T. Barnum musical?

Yeah.

It was surprising enough to see you, the science teacher, on stage. Everyone else was a student. But the really shocking thing was that you had shaved your beard. You came out beardless and you danced all around, singing this song about feeling like a kid again. Suddenly you were this big, lovable softie. When you took the beard off, a wall came down.

I hadn’t thought about it, but that makes perfect sense.

Your smile beamed. For the first time, maybe, people could see what it looked like. The smile.

All through the rehearsals, there was no discussion of the beard coming off. But my wife and I, weeks before the show, talked about how weird it was for me to be up there, singing like a kid, and having this beard on. I said, “I think I’ll shave it off.” And she said, “Well, I guess so.” She wanted to know if I’d ever shaved it off before.

Had you?

No, never since 1968 when I started growing it, in Japan, in my first year of teaching. Not for an illness or anything. So during the opening numbers of the show, I went back to the restroom and shaved it off. It was incredibly painful. The whole time I was doing it, I kept asking myself, “Why did I think to do this? But oh well, I can’t stop now, with half the beard gone. I have to continue.”

Was it physically painful?

Oh yeah. I had a styptic pencil with me to stop the bleeding, and I used bits of toilet paper. I didn’t think the bleeding would stop before I had to head down the aisle, but it did. My own mother-in-law didn’t recognize me. My wife had to tell her it was me. And the looks on the faces of the kids who were supposed to be responding to my cues, they were incredulous. Their jaws were down to their knees.

It was shocking, you in the spotlight, beardless.

And that was the desired reaction.

Does the beard keep you warm?

[laughs] Not particularly. It’s good when you’re skiing. In the summer, I keep it short. There were some times in the seventies when I wore it long, when it was momentarily fashionable, but since those days I haven’t let it grow longer than an inch-and-a-half or so.

Are you the kind of guy who’s sensitive to fashion trends? I wouldn’t guess that you are.

Not particularly. I buy clothes for their particular, you know, use-value rather than for how they look. I bought Carhartt working clothes long before they were fashionable. I buy them because they’re the best.

In this first drawing, Hangin’ Hawkins, with the “1-800-GALLOWS,” I’ve put you in… Do you have the drawings with you?

Yeah, they’re right here.

I’ve put you in a cable-knit turtleneck sweater and white loafers. If you were to go to the gallows, what kind of clothes would you wear? Were these a good guess?

[laughing] I don’t know. I always think of that situation. I mean, not for myself to be in it, but you wear whatever the person’s given you to wear. You don’t have a choice.

If you had to make one last fashion statement on the gallows, though.

I don’t know. I guess it would depend on what I was being hanged for.

For being a mean teacher.

[hint of annoyance] Yeah, right. I wouldn’t care what I was wearing at that point. The sweater in that drawing is something I would have worn a lot in the winter. But I don’t understand the shoes.

I think those were the shoes I felt comfortable trying to draw. My dad had some loafers with elaborate, tasseley tongues. They weren’t white.

They wouldn’t have been my shoes, that’s for sure.

• • •

Let’s switch over to the meat cleaver drawing.

Okay.

That’s Bobby Larkin holding the cleaver.

What was the students’ impression of Bobby Larkin?

He was not a very smart kid, but he was a fun kid. He would do things that were, uh… He was my friend, but I didn’t see him as an equal. I took advantage of the kid. There was this incident where I had this idea to send you magazine subscriptions using Business Reply Mail cards.

Uh-huh.

That was my idea.

Uh-huh.

I’d bring these subscription cards from my mom’s magazines into school, and my regular friends—my bring-home friends—thought the idea of sending you the magazines was kind of funny, but I didn’t ask them to do it. I didn’t think they would have actually done it. They liked the idea in theory.

You didn’t do it, did you?

I did do it.

Oh, it was you? It wasn’t Bobby Larkin?

It was Bobby and me, both.

Oh, okay. Because we assumed right off the bat—I told my colleagues about it—we assumed it was Bobby Larkin because we couldn’t think of anyone else who would do that. Although I do have to admit, we sort of wondered how he would have gotten the idea. [laughs] Luckily, it wasn’t a big problem. All I had to do was call up the magazines and tell them I hadn’t subscribed, and that usually took care of it.

So they actually sent you copies of these magazines? Better Homes and Gardens?

Yeah, whatever it was.

Did you read any of them?

Oh, I don’t know. At first I assumed it was a computer error. My information accidentally got entered in the wrong place. But after several magazines came, one of my colleagues said, “Someone’s doing it to jerk your chain.” Our person of choice was Bobby Larkin because, I don’t know if you knew this, but we were afraid of him.

[laughs] I didn’t know.

Not terrifying afraid, but we were afraid in the sense of thinking he might do something. I mean, you know when Columbine happened? We all thought, “This is something that Bobby Larkin could have done if the situation were different.”

Man, I don’t know. I guess I can see that perspective. But one thing I liked about Bobby was that what you saw was what you got. He wasn’t a seether. Maybe he was scary because he was incapable of creating a façade, or seemed to be. Anyway, his recklessness was different and exciting. He was not afraid, so to speak, to get his name on the board.

A lot of our fear was centered around the kinds of things that you might not have seen. Things he did to other kids. And the kinds of things he wrote about were worrisome. For a kid to be able to express those kinds of things, in writing, in school, as part of an assignment, made him a candidate for “let’s watch him.”

So his writing was expressive. Was it good?

It was really bad. Extremely violent. And, to be fair, all boys in fifth and sixth grade, or almost all, write that kind of stuff. I did too. One of my hobbies when I was that age was planning bank robberies.

[laughs] Neat.

[laughing] We even went as far as to go downtown and walk into a bank so we could see what it looked like inside. I mean, it didn’t last long. It went on for about a month and then we ran out of gas and went on to something else. But Bobby’s stuff seemed strange to us.

• • •

We talked about you shaving your beard for P. T. Barnum. There was this other weird, surprising fifth-grade theater moment. I don’t remember the details, but it was at the spring talent show…

The blackface thing?

Yeah! On talent show night, I just remember these two girls coming out in front of the whole school—teachers, parents, everyone—with shoe polish on their faces. And they spoke with this thick, embarrassing drawl. What happened?

What happened was we had some kids who wanted to do this skit. So they went through all the rehearsals, and they never used blackface. They never suggested it or brought it up. While they were preparing, we were very careful to have discussions with them about one particular part of the skit...

What was the skit about?

Well, in this one part there were two mothers, one black and one white. Each one had a child. There were black and white characters, but the skit wasn’t about being black and white. We had discussions with the kids, telling them to be sure they didn’t camp it up.

Were they using the thick drawl in rehearsals?

They were trying all kinds of things. We asked them to be careful. But blackface never entered into it.

Did the students write the script?

No, it was a canned script. Anyway, two of the kids in this skit were really into acting. I remember—and forever this moment has hung with me—I remember I was backstage walking around in the area where they were preparing and I leaned my head in the door and said, “You guys are on next.” And I saw them putting on blackface. But it was just a fleeting instant, and I moved on to what I was doing, and they went onstage. It didn’t register on me quick enough to stop them. I mean, I could just say I never saw them at all. But I did see them. It didn’t dawn on me fast enough to say, “You can’t do that.” And so they went on, and oh man, all hell broke loose. We scheduled several meetings with parents. We explained that the kids didn’t have any idea that this was wrong. It took about two weeks for everyone to come out mollified.

I remember a big school meeting the day after the show. I was excited that something big was happening. People had messed up. We were missing class. During the big meeting, you stood up in front of everyone and you broke into tears. Before that, I don’t think I’d ever seen a teacher cry.

That’s because you weren’t in my literature class. Every time I would finish a sad book, I’d always cry.

Really?

Oh yeah. There’s a book called A Day No Pigs Would Die. I read it aloud with the kids every other year I was at Maumee Valley, and I’ve never been able to get through the ending without crying. Kids would tell their younger siblings about it, to look forward to it.

So your tears became an event to anticipate. Old Faithful.

Yeah.

What happens at the end of the book?

The main character buries his father and takes over as a man in the family. And the way it’s written is so touching. Even the hardest kid gets touched by the end of that book.

I see.

Even Bobby Larkin might have been touched.

• • •

I’m happy we could talk. I’m going to send you a subscription to Cabinet. Don’t cancel it.

Oh, sure. If you need more, call back.

PS While preparing for this conversation, I called 1-800-GALLOWS, the phone number on the gallows in the Hangin’ Hawkins drawing. The number, I learned, belongs to Ventura Metals, a manufacturing company in Ventura, CA. (Motto: “Meeting all metal needs.”) At their website, www.venturametals.com [link defunct—Eds.], I discovered that 1-800-GALLOWS also spells 1-800-4-ALLOYS—the company’s official phone-number spelling.

I called Ventura Metals back and asked if they could make me a makeshift gallows—a 15-foot steel pole, bent 90 degrees at the 10-foot mark, suitable for anchoring in the ground and suspending 500 pounds. It turns out that, yes, with two weeks lead time, for approximately $700 postpaid, the people at 1-800-GALLOWS will make-to-order and ground-ship, to your United States residence, an actual gallows.

- All names besides Mr. Hawkins and P. T. Barnum have been changed.

- Upper Intermediate; the title of the combined fifth and sixth grades at Maumee Valley Country Day School.

Mr. Hawkins is a teacher contentedly retired to Hobbitish putzing. He lives in northwest Ohio.

Brian McMullen is managing editor and graphic designer of Cabinet.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.