Inventory / Fallen Figures & Heads: Leon Golub’s Lists

The poetry of the archive

David Levi Strauss

“Inventory” is a column that examines or presents a list, catalogue, or register.

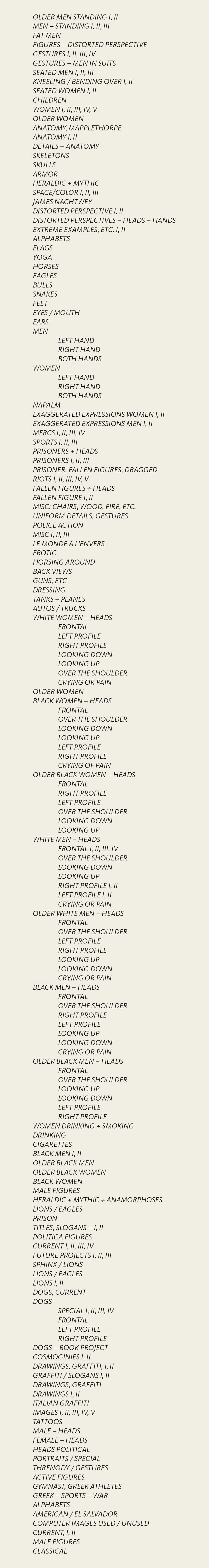

This issue marks the debut of “Inventory,” Cabinet’s new occasional column tracking the types of linguistic and cultural surplus to be found in the structures and content of lists, registers, and catalogs. The inaugural installment of the column brings together two collaborators and friends, painter Leon Golub and writer David Levi Strauss. It was in a published conversation between the two men that Cabinet’s editors first learned of the extensive classificatory system created by the artist for his archive of thousands of photographs. Cut out from books and periodicals over the years, these pictures function as source material for his signature scenes of physical, psychological, and social extremity. In the following essay, Strauss not only sketches the etymological, sociohistorical context of lists in general, but also identifies a kind of latent poetry that resides in Golub’s specific categories.

The list could surely go on, and there is nothing more wonderful than a list, instrument of wondrous hypotyposis.

—Umberto Eco

People are divided over them. Either one makes lists or one doesn’t, and the ones who do are changed by them. They start making lists as an aid to memory and to bring a sense of order into their lives. But in time, the lists work so well that their makers drift into amnesia and chaos. They develop unhealthy attachments to their lists, as their work is increasingly cut out for them. Finally, they are left helpless and listless.

This progression is presaged in the etymology of lists, where the boundaries between list and lust, or list and listen, are quite porous. The currently prevalent sense of list as “catalogue” has a Teutonic origin, including the German leiste, “a border or edging,” which was eventually transferred to a “strip” of paper or parchment containing a “list” of names or numbers arranged in order for some specific purpose. But the parallel sense of list meaning “to choose, desire, or have pleasure in” is never far away, and this one includes lust, from the Anglo-Saxon lystan, “to desire.” The desire or inclination of a ship to lean one way or the other makes it list, and a person is described as listless when he or she exhibits a lack of inclination, leading to an overly upstanding stasis.

Eco’s wondrous instrument points to the work of lists as sketches, outlines, or patterns, and the Greek hupotuposis derives from tipos, “an impression, form, or type.” When lists become compendious, they list toward the rhetorical figure of hypotyposis, “by which a matter [is] vividly sketched in words” (according to Liddell & Scott’s Greek English Lexicon). Sextus Empiricus titled his summary of the doctrine of skepticism The Pyrrhonian Hypotyposes.

Writers are especially susceptible to a kind of list-lust that borders on womb-envy, since lists were there at the misty beginnings of literacy, in those lists of sacks of grain and heads of cattle inscribed on clay tablets at Uruk, in what is now Iraq. In lists, writers intimate origins. They hear the Homeric catalogues, the Biblical genealogies, Whitman’s Leaves, and Ginsberg’s Howl. The list is the linguistic reflection of the unstructured world; it’s what’s left when structure is pulled out. Paradoxically, the list may also be the ultimate structure. When everything is compressed to its least complicated form and relation, it’s all a list. Life consists, finally, of one damn thing after another.

When I first spoke with Leon Golub about his use of photographic images as source material for his paintings, he told me that he has “huge files of images and image-fragments. I virtually sense myself as made up of photos and imagistic fragments jittering in my head and onto the canvas.” So when he sent me the list of headings in his image files, I took them as a kind of self-portrait, and immediately began making poems out of them, for Leon. Actually, the first one, written from only the first page of the list, was a double portrait of Leon and his wife, artist Nancy Spero:

Extreme Examples

(for Leon & Nancy)

the anatomy of current

older men, standing

with armored skulls,

ears, eyes/mouth, and feet

like alphabets.

And seated women, bending over

eagles, bulls, and snakes

in distorted perspective—

current, too,

heraldic and mythic as flags.

Then I remembered a poem I’d written long ago in Venice, an agnostic hymn to modernism called “Peg’s House,” formed from titles of works in the Peggy Guggenheim collection, which began “Blu su blu in her bedroom, / to see how the modern has aged.” Since this rhymes pretty well with Leon’s various wry proclamations about modernism in his works and writings (including the succinct “Modernism Is Kaput”), I was encouraged to draw more poems from Leon’s lists:

Extreme Examples, Etc.

The Dogs’ current book project,

“Le Monde à L’Envers,” entails

their distorted perspectives

on tattoos, black men crying,

women drinking and smoking,

Italian graffiti,

and James Nachtwey.

Fat men in armor,

looking up and looking down,

sport the exaggerated expressions of

prisoners or fallen figures;

while white women,

horsing around with lions and eagles,

create flags and yoga.

But eventually, all of these

active figures, with their

sometimes erotic (over the shoulder) back views,

become mere skeletons with uniform skulls

due to the actions of political figures

with titles and slogans,

using images and napalm.

So, a new form of imagism— list imagism, or, as Leon might have it, “jittery image-jism”—was born.

Leon’s lists of image files refer to real filing cabinets containing actual, rather than virtual, folders and documents, so the items on this roll name images one can hold in the hand. This physical referent, along with the abrupt juxtapositions of the headings, increases what Derrida called “archival violence” (laying down the law and giving the order), and gives this list the edgy aggressiveness of Leon’s paintings (recalling the old sense of list as “a place of combat or contest”). And the pared down, fragmentary quality of the list—highly compressed language with large gaps between fragments—is also much like Leon’s recent paintings, done in what he’s called his “Late Style,” after Adorno, who wrote that late works by significant artists are “relegated to the outer reaches of art, in the vicinity of document.”

The power of subjectivity in the late works of art is the irascible gesture with which it takes leave of the works themselves. It breaks their bonds, not in order to express itself, but in order, expressionless, to cast off the appearance of art. Of the works themselves it leaves only fragments behind, and communicates itself, like a cipher, only through the blank spaces from which it has disengaged itself.

David Levi Strauss is the author of two recent books of essays on art and politics: Between the Eyes (Aperture, 2003) and Between Dog & Wolf (Autonomedia, 1999).

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.