Hummingbird Futures

Theodor Nelson and the creation of hypertext

Daniel Rosenberg

The voice belongs to Theodor Holm Nelson, inventor of the terms “hypertext” and “hypermedia,” apostle of the home computer, Web visionary, self-appointed “officer of the future,” and forecaster of so much that we now take for granted in the electronic universe. If the tenor of this statement from the 1980s is more triumphant than most, the discourse is readily recognizable. Indeed, by now, the rhetoric of information explosion must strike us as less surprising than the time frame of the forecast: decades—didn’t that seem an awfully long time to wait?

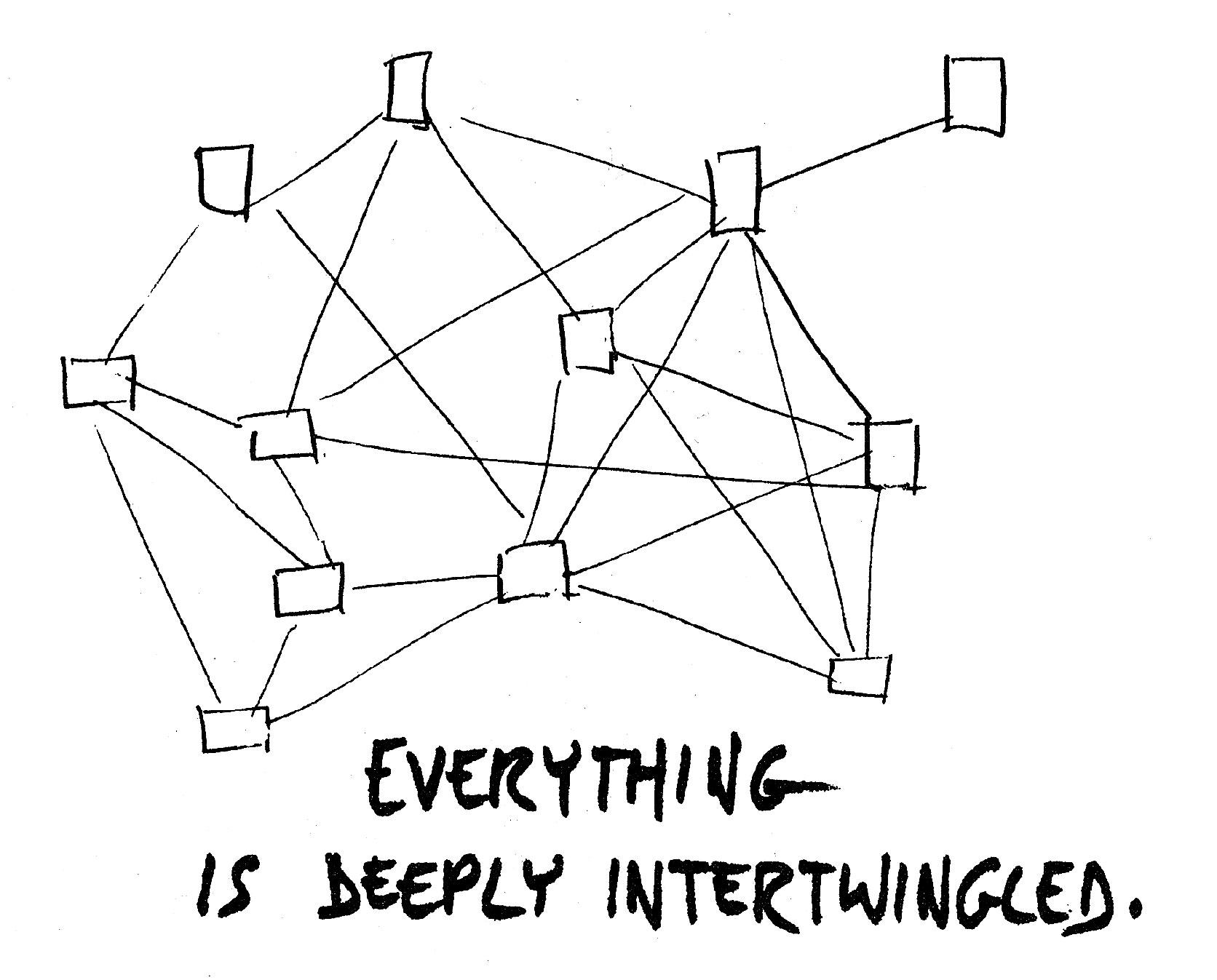

Since the 1960s, Ted Nelson’s prescience has been his trademark. Before the first home computers, he called for a home computer revolution. He dreamed of a word processor before one was designed. Already in the 60s, he argued that the information future would materialize as an interconnected network. And, most famously, he dreamed that the computer would free writing from the strictures of linearity, that electronic text would take the form of an open and multi-dimensional linking structure that in 1965 he named “hypertext.” [2]

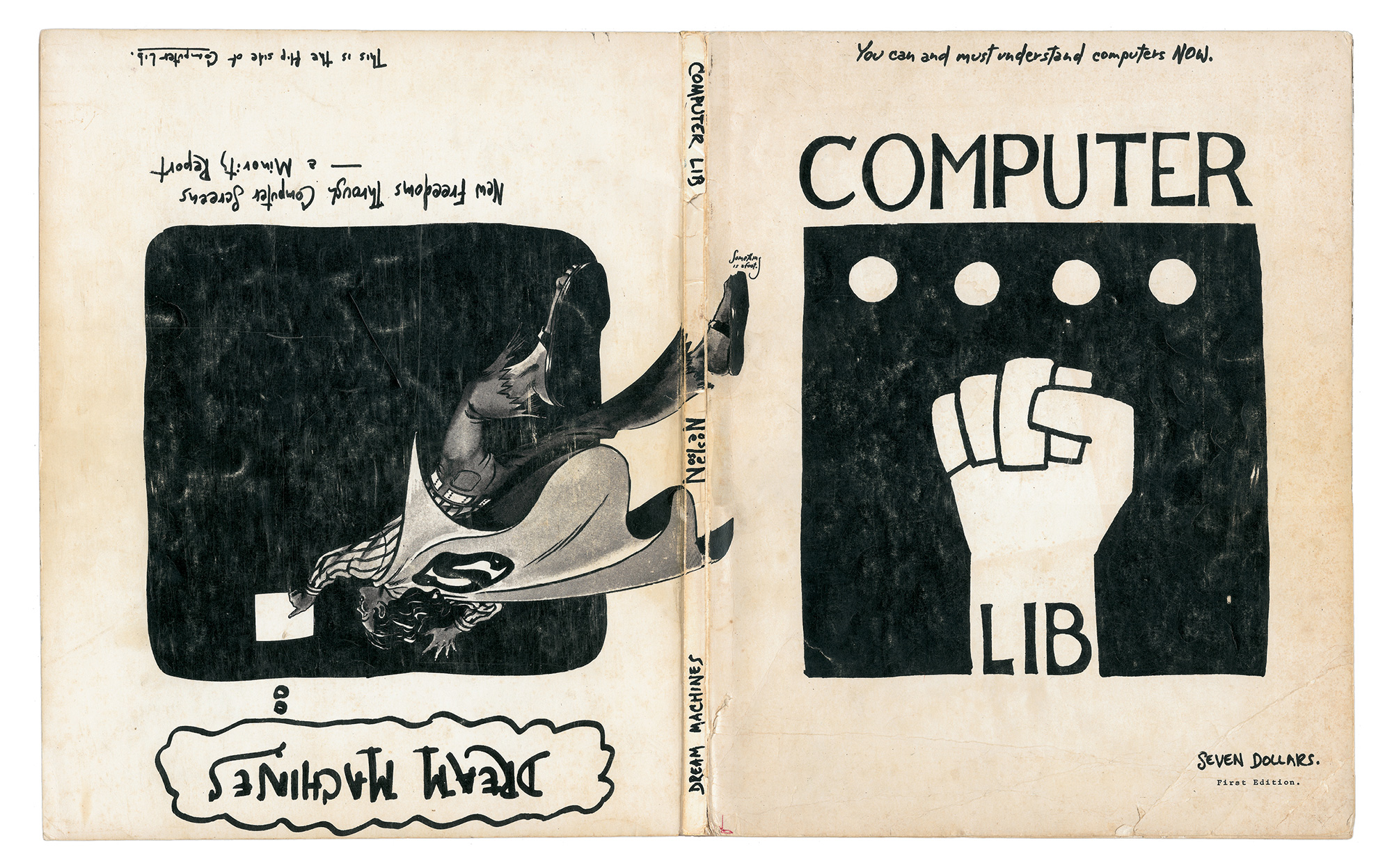

Nelson is not known principally as a technical innovator; he has primarily been thought of as a seer. His most famous writing, a hypertext manifesto called Computer Lib/Dream Machines self-published in 1974, remains an underground classic of hackerdom.[3] His more recent work, especially his 1980 Literary Machines, revolves around the still-in-progress design of a “transclusive” hypertext network called Xanadu™. To many, this project seemed chimerical before the rise of the Internet and the graphic and textual interfaces of the World Wide Web. Since then, perceptions of the information universe have changed, and perceptions of Nelson have changed with them. Indeed, some have argued that the important parts of Nelson’s dream have already been achieved. Nelson disagrees. His concept of Xanadu involves a dynamic structure more powerful and more flexible than the currently available network. Nonetheless, the Web has made it clear that the electronic word is reformulating many of our assumptions about how textuality and information operate, in ways that have given Nelson’s ideas new currency. In the last decade, he has been cited more and more in academic and popular contexts. His older work has been reissued. As he put it, with the explosion of the Web, he has been “abruptly promoted from Lunatic to Visionary.”[4]

But for all its resonance with Nelson’s career, the label “visionary” has never quite fit. His perspective was always paradoxical. Like many of his contemporaries, in the 1960s and 1970s Nelson regarded the future with both hope and fear. He predicted coming social and ecological disasters, but he argued against accepting such predictions as written in stone, believing it is up to us “to make ... predictions come out wrong.”[5] For Nelson in the 1970s as now, whatever hope we might have lies in a (computer-aided) multiplication of intellectual pathways and possibilities, in the system of “envisioning complex alternatives” that he named “hypertext.”

According to Nelson, with the exception of the most rudimentary examples, all text points to other text outside of the single, supposedly closed sequence; all sources are ringed by satellite sources that encourage readers to make explicit or implicit comparisons, mental leaps, and intellectual choices. As he explains in Literary Machines,

Many people consider [hypertext] to be new and drastic and threatening. However, I would like to take the position that hypertext is fundamentally traditional and in the mainstream of literature. Customary writing chooses one expository sequence from among the possible myriad; hypertext allows many, all available to the reader. In fact, however, we constantly depart from sequence, citing things ahead and behind in the text. Phrases like “as we have already said” and “as we will see” are really implicit pointers to contents elsewhere in the sequence.[8]

This broad conception of hypertext explains how electronic writing can be understood as sharing characteristics of other written forms. “Hypertext can include sequential text, and is thus the most general form of writing. (In one direction of generalization, it is also the most general form of language.)”[9] No writing or utterance travels in a straight line. None stands alone. Hypertext in the largest sense is both the interconnective tissue of lexias that make up a given textual unit such as a “book” and the matrix of external references from which every “book” must draw its filaments. From this perspective, literature appears not as a collection of independent works, but as “an ongoing system of interconnecting documents.”[10] We read and write, in other words, in a world bigger than books, and Nelson refers to this theoretical realm of lexical plenitude as the “docuverse.” In the docuverse there is literally no hierarchy and no hors-texte. The entire paratextual apparatus inhabits a horizontal, shared space.

Our design [for the hypertext system Xanadu™] is suggested by the one working precedent that we know of: literature. ... We cannot know how things will be seen in the future. We must assume there will never be a final and definitive view of anything. And yet this system functions. LITERATURE IS DEBUGGED.[11]

Technology, he argues, allows us to see dimensions of literature that remained obscured in the print era. At the same time, literature and scholarship as traditionally construed offer an intellectual and cultural model which, while far from perfect, has nonetheless proved capable of expressing complexity, ambiguity, and responsibility.

The assertion that “literature is debugged” captures much of what makes Nelson different from his technologically-oriented peers in information theory. But his “systems humanism” is also echoed by a number of contemporary critics who have taken a middle road in what is often a depressingly binary debate on the value of electronic writing. J. Hillis Miller, for one, appreciates both the Proustian possibilities inherent in hypertextual errancy and the hypertextual quality of Proust’s own meditations. At the same time, he warns against a naïve implementation of hypertext, and especially against naïve readings in it. For example, in his review of a hypertexted version of Tennyson, Miller argues that the very paths and links offered by the system imply that:

a Victorian work ... is to be understood by more or less traditional placement of the poem in ... its socio-economic and biographical context, by reference, for example, to the building of canals in England at the time. The apparent freedom for the student to “browse” among various hypertext “links” may hide the imposition of predetermined connections. These may reinforce powerful ideological assumptions about the causal force of historical context on literary works. ... Hypertext can be a powerful way to deploy what Kenneth Burke called “perspective by incongruity,” but it can also be conservative in its implications.[12]

Likewise, for Terrence Harpold, to treat “the link as purely a directional or associative structure is ... to miss—to disavow—the divisions between the threads in a hypertext. ... What you see is the link as link, but what you miss is the link as gap.”[13] Both arguments point to advantages in Nelson’s concept of the Xanadu interface as opposed to the systems of electronic hypertext and the Internet as currently configured. The point of Xanadu is to make intertextual messiness maximally functional, and in that way to encourage the proliferation and elaboration of ideas.

Such a structure has a variety of advantages. Nelson sees a guarantee of intellectual property: “This system allows all the appropriate desiderata of copyright to be achieved: one, payment for the originator; two, credit for the originator; three, nothing is misquoted; four, nothing is out of context.”[16] The goal of Xanadu, on one hand, is total instantaneous information access. On the other, it is continuous revelation of interconnectedness without the dilution of specificity. At one pole stands the dream of a universal archive, at the other, the fragmented and nomadic appropriation of knowledge of all sorts. Hypertext becomes a system for the production and management of such “loose ends.”

The question of loose ends has always been crucial for Nelson. A meticulous taker and retaker of notes, he was a sociology student in the early 1960s when he first encountered computers and imagined Xanadu. In that pre-word-processing age, it was evident to Nelson that computers could not only be used as typewriters, but that they could function as archiving, database, and communication systems. If, as he believed, the problem with conventional writing is that it tends to limit intellectual options by channeling them in only one direction, then electronic hypertext could mirror and supplement the lightness and fluidity of creative thought. Fishing Vonnegut-like for a name that might capture the humor and complexity of hypertextuality, he spoke of “grandesigning, piece-whole diddlework, grand fuddling, metamogrification, and for that most exalted possibility, tagnebulopsis (the visualization of structure in the clouds).”[17] A reporter once asked Nelson whether the transclusive Xanadu paradigm might not be symptomatic of a generalized attention deficit disorder. He responded, “We need a more positive term for that. Hummingbird mind, I should think.”[18] And it may be that hummingbird mind has finally found its technology. The striking success of hypertext and hypermedia systems in all sorts of applications, from reference works and technical manuals to works of literature, art, and games, attests to the generality of Nelson’s vision. But there is more. Vivid and sensitive a writer that he is, Nelson also captures something like the unconscious of these practices.

XANADU™

One of the great unfinished dreams of the computer field ... Literary System, Storage Engine, Hypertext and Hypermedia Server, Virtual Document Coordinator, Write-Once Network Storage Manager, Electronic Publishing Method, Open Hypermedium, Non-Hierarchical Filing System, Linked All-Media Repository Archive, Paperless Publishing Medium, and Readdressing Software. The Magic Place of Literary Memory™.

Xanadu, friend, is my dream.

The name comes from the poem; Coleridge’s little story of the artistic trance (and the Person from Porlock) makes it an appropriate name for the pleasure dome of the creative writer. The Citizen Kane connotations, and any other connotations you may find in the poem, are side benefits.

I have been working on Xanadu, under this and other names, for fourteen years now.

Make that twenty-seven years.[19]

Nelson’s narrative echoes the associative logics of the Xanadu system. It also self-consciously recalls the way in which the Romantic poets put into question the idea of completion itself. Hence Nelson’s fascination with Coleridge’s famously unfinished poem, Kubla Kahn. The poem is a curious object. It is a vision of paradise that came to the poet unmediated, in a dream state, or so Coleridge claims. But Coleridge never gives his reader access to this moment. He tells us that the published poem is only a fragment, the bit of writing that he was able to do before his transcription was interrupted by a visitor from Porlock. What is interesting about the poem is that it is in every way a model hypertext. In the first instance, the apparently unmediated version of the poem is already a vision of a vision, Coleridge’s quotation of what the Khan saw. And in the version that we get as readers, it is citational on another level: it is Coleridge’s transcription and annotation of his own memory. Moreover, in keeping with the Romantic resonance of the poem (“a vision in a dream, a fragment”), Nelson’s narrative of Xanadu also goes back to childhood. He contrasts his own experience in school with the free play of ideas that he observes among contemporary groups of computer kids. According to Nelson, schools are the principal enforcers of the fictions of linearity. “The very system of curriculum, where the world’s subjects are hacked to fit a schedule of time-slots, at once transforms the world of ideas into a schedule (Curriculum means ‘little racetrack’ in Latin.) A curriculum promotes a false simplification of any subject, cutting the subject’s many interconnections and leaving a skeleton of sequence which is only a caricature of its richness and intrinsic value.”[20] The goal of Xanadu, he says, is to make the world “safe for smart children.” He might just as well have said, “smart children of all ages,” for among smart children, he clearly includes himself.[21]

For Nelson, writing or reading is always a process of restoring something lost. If, in the more mundane sense, every act of composition is an act of creation, in the terms of the docuverse, every act of creation is, in effect, a mapping of forgotten hypertextual space. At a deeper psychic level, every linguistic act is an act of contact with a lost body through a “magic place of literary memory.” Info-discourse provides us with a newly structured figure of memory. It at once speaks of system storage, of the unexamined and recaptured links between ideas, and of the problem of consciousness slipping from our grasp.

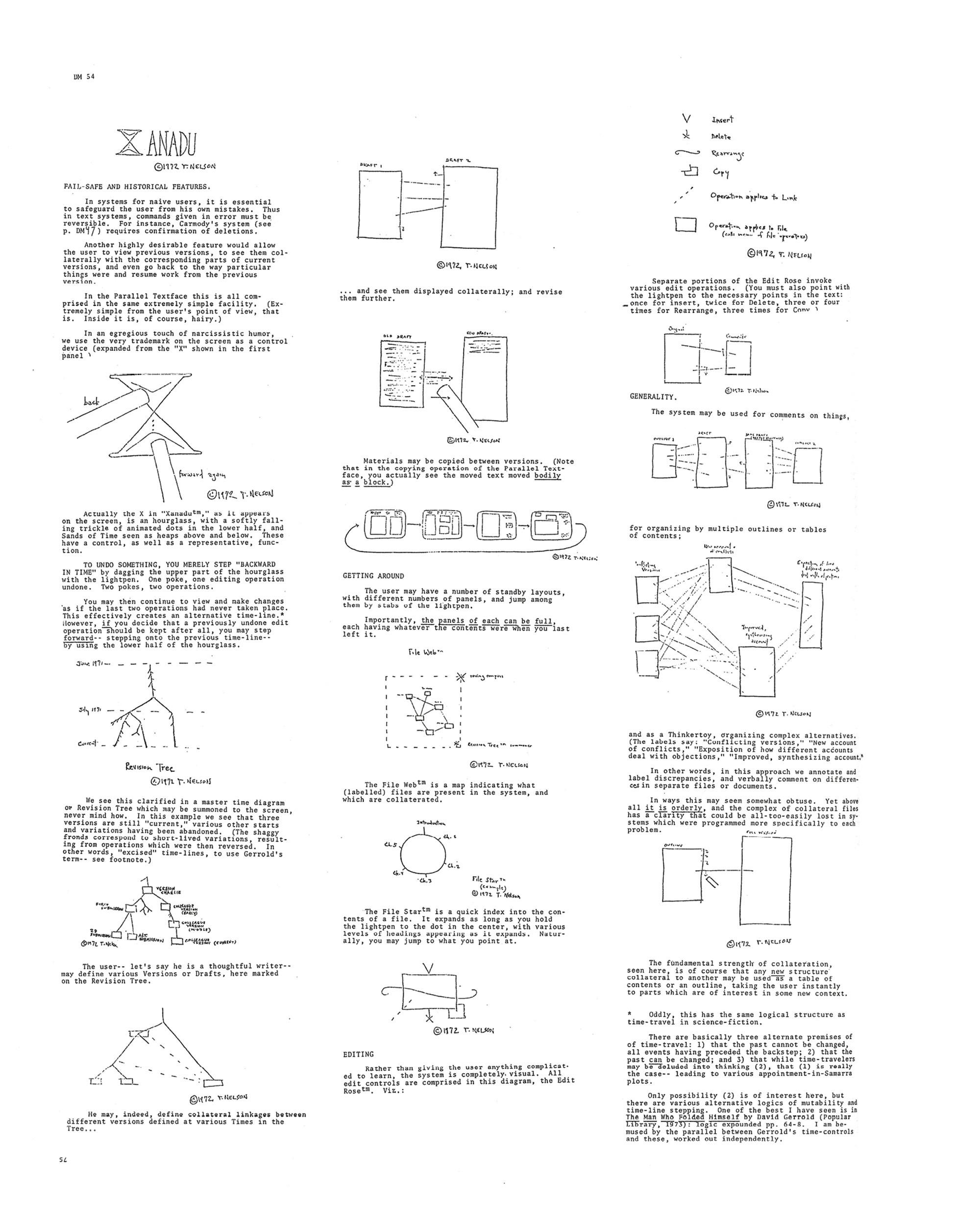

Xanadu, then, operates as prosthetic memory. It stores everything in alternate versions. Nothing need be lost. A mistaken path can always be retraced, a lost reference recovered, a silenced voice revived. Nelson even compares this process of “versioning” to time-travel, in which “the past can be changed.”[22] Users of the Xanadu prototype notice that the cursor takes the shape of an hourglass. “TO UNDO SOMETHING, YOU MERELY STEP ‘BACKWARD IN TIME’ by dragging the upper part of the hourglass with the light pen. ... You may then continue to view and make changes as if the last ... operations had never taken place.”[23] Historically, of course, writing has often figured as a transit across time; as Friedrich Kittler puts it, “every book is a book of the dead.”[24] In this respect, electronic writing is no different from other kinds. But electronic writing also energizes the fantasy that death might not be permanent, that the text would not only testify to past activities, but that those activities themselves might be re- or unwritten. Through the chiasmatic X of Xanadu, the sands of time pass back and forth.

At the same time, hypertext embodies the fantasy that the computer screen might open. Here, the organizing principle is not time’s arrow but the human body. To date, perhaps the most interesting meditation on this metaphor is Shelley Jackson’s pioneering “hypertext novel” Patchwork Girl, which weaves together elements of Mary Shelley, L. Frank Baum, and varieties of literary criticism. Jackson explicitly energizes the body metaphor by leading her reader through phrenological maps and anatomical graveyards, inciting the construction of multiple “Patchwork Girls.”[26] Nelson’s metaphorizing of bodily rather than linear time, meanwhile, includes a figuration of the light pen (which he uses rather than a mouse) as a scalpel to cut across the screen. Of course the body metaphor is in no special way the province of hypertextual representation. From the cabalistic mapping of Scripture onto the flesh to metaphors like the ship of state, the body provides a natively comprehensible trope for functional interconnection and/or hierarchy. But, as Anne Balsamo and others have pointed out, the human body also plays a central role in fantasies of cyberspace precisely because these fantasies so often rely on an assumed negation or evacuation of it.[27] As much as the computer screen is fantasized as a new domain of freedom for consciousness, it also seems always to hint at corporeal amputation or atrophy.

Consider, for example, “fantics,” Nelson’s term for a science that would include the theoretical structure of virtualities, but also the old terrain of psychology, physiology, and epistemology—everything that concerns the possible address of our perception. It is “the art and science of getting ideas across, both emotionally and cognitively.”[28]

Should I have called it TEACHOTRONICS? SHOWMANSHIPNOGOGY? INTELLECTRONICS? ... THOUGHTOMATION? MEDIA-TRONICS? ... Okay, so I wanted a term that would connote, in the most general sense, the showmanship of ideas and feelings—whether or not handled by machine. I derive “fantics” from the Greek words “phainein” (show) and its derivative “phantastein” (present to the eye or mind). You will of course recognize its cousins fantastic, fantasy, phantom. ... The word “fantics” would thus include the showing of anything.[29]Nelson’s argument for the reality of “fantic space” should not come as a surprise, steeped as we now are in promotions of “virtual reality.”[30] What is interesting about his statement is that he dispenses with any hard and fast distinction between the presentation of “reality” and that of “virtuality.” In theorizing screen-based display, fantics examines the ghost of the physical body—which persists in the term, like a phantom limb. In the Xanadu universe, an electronic Rapture is supposed to take place in word and image, and our bodies as well as our minds will link up with machines. As Nelson explains, “Everything has a reality and a virtuality. Good examples are buildings, equipment, cars. ... The extreme cases are the movie, which is all virtuality, and the fishhook, which has no virtuality—no conceptual structure or feel to the victim—until too late.”[31] The fantic computer, in his conception, becomes an extension of ourselves. For better or worse, the computer becomes prosthetic.

But, in contrast to most of his contemporaries, Nelson understands this eventuality not so much as a passage into the future as a passage into a certain kind of past, into the childbody of the mind. What we see in the image of the child glued to the computer screen (an image repeated throughout Nelson’s works) is an imagined experience of communion, body and mind reunited in dreamspace.

Almost everyone seems to agree that Mankind (who?) is on the brink of a revolution in the way information is handled, and that his revolution is to come from some sort of merging of electronic screen presentation and audio-visual technology with branching, interactive computer systems. ... Professional people seem to think this merging will be an intricate mingling of technical specialties. ... I think this is a delusion and a con-game. I think that when the real media of the future arrive, the smallest child will know it right away (and perhaps first). ... When you can’t tear a teeny kid away from the computer screen, we’ll have gotten there.[32]This is the present experience toward which all of Nelson’s work aims. Hypertext is a name for this physical pleasure of thought, for a kind of representation that reinforces and operationalizes hummingbird mind. Nelson’s efforts do not revolve around the fantasy of the dissolution of the body into data, but rather celebrate the re-access of the lost, free childbody through the medium of fantic space.

This is the special sense of Xanadu as a “magic place” of memory, a realm of unchained creativity that is always hypereventually present. The design expresses Nelson’s imagination of the information future as a hyperexperience of childhood, the chiasmatic return through the looking-glass of the computer screen to a pre-curricular mind. Via a kind of time travel, Xanadu gives body (back) to acts of textual imagination. The model is less Borges’s “Garden of Forking Paths” than it is Jackson’s operationalized L. Frank Baum: the encyclopedic dream as electronic story book.

In one respect, such observations might be made of much hypertext writing and theory in the last 30 years. There has been a general movement to highlight the intellectual and imaginative potential of non-linear form, and literary utopia has evolved into hetero- or hypertopias. What is most interesting about Nelson is not his undeniable role in propelling this movement, but his scrupulous problematization of a materiality that is often absent from the work of other writers. Even as Nelson releases the multidimensionality of seemingly traditional, linear texts, he insists upon the value of so-called traditional writing, upon its protection from everything that might seek to supplant it or its appeal to the creative imagination.

The storybook analogy suits Nelson. Like instructive fables, his work helps us to discriminate among the rhetorics and practices of our possible information futures. These networks of praxis are stitched from traditional fabrics of future and past: fabrics of progress, revolution, and millennium; of nostalgia, memory, and return. In this respect, what is important in Nelson’s work is not the idea or practice of non-linearity per se, but rather the insistence that our futures were never all that linear to begin with. The seams of the patchwork show. Whatever else it is, Xanadu is a system for marking intellectual paths, and unlike so many information and cybernetics theorists, Nelson’s primary concern has never been speed or scope in itself. Xanadu is distinctive principally because it presents itself as patchwork, because it insists that in fantic space all the joints be left showing. Of course there are elements of what Xanadu promises that are utopian, nostalgic. But if Xanadu is a phantasm, and if time will not turn backward because we touch a floating hourglass with a magic cursor, it is equally true that our futures make no sense unless we reckon with our longing for such possibilities.

- Theodor Holm Nelson, Literary Machines: The Report on, and of, Project Xanadu™ Concerning Word Processing, Electronic Publishing, Hypertext, Thinkertoys, Tomorrow’s Intellectual Revolution, and Certain Other Topics Including Knowledge, Education, and Freedom, revised ed. (Sausalito: Mindful Press, 1987), 0.11–12.

- The basic literature on hypertext is George Landow, ed., Hyper/Text/Theory (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994); Hypertext 2.0: The Convergence of Contemporary Critical Theory and Technology (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997).

- Theodor Holm Nelson, Computer Lib/Dream Machines (Self-Published, 1974); idem., Computer Lib/Dream Machines (Redmond, Wash.: Microsoft Press, 1987). The two books are bound together, upside down and back-to-back. Citations are from the 1987 edition.

- Nelson, Computer Lib, p. 16.

- Ibid., pp. 175–176.

- Nelson, Dream Machines, p. 50.

- Ibid.

- Nelson, Literary Machines, 1.17.

- Ibid., 0.3.

- Ibid., 2.2.

- Ibid., 2.9–2.11.

- J. Hillis Miller, “The Ethics of Hypertext,” Diacritics 25.3 (Fall 1995), pp. 27–28.

- Terrence Harpold, “The Contingencies of the Hypertext Link,” Writing on the Edge 2.2 (1991), p. 134.

- See also Theodor Holm Nelson, “Opening Hypertext: A Memoir,” in Literacy Online: The Promise (and Peril) of Reading and Writing with Computers, in Myron C. Tuman, ed., (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1992).

- Nelson, “Opening Hypertext,” p. 55.

- Ibid., pp. 55–56.

- Nelson, Dream Machines, p. 37.

- Gary Wolf, “The Curse of Xanadu,” Wired Magazine 3.06 (June 1995),

- www.wired.com/wired/archive/3.06/xanadu.html. Nelson took issue with aspects of Wolf’s article. See Theodor Holm Nelson, “Errors in ‘The Curse of Xanadu’ by Gary Wolf,” 17 December 2002, www.xanadu.com.au/ararat.

- Nelson, Dream Machines, p. 141.

- Nelson, Literary Machines, 1.20.

- See also, Theodor Holm Nelson, “Barnumtronics,” Swarthmore College Alumni Bulletin (Dec. 1970), pp. 13–15 (cited in Nelson, Dream Machines, p. 5).

- Nelson, Dream Machines, p. 43.

- Ibid., p. 49.

- Friedrich Kittler, “Gramophone, Film, Typewriter,” trans. Dorothea von Mücke, October 41 (1987), p.107.

- Italo Calvino, Invisible Cities, trans. William Weaver (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1974), p. 29.

- Shelley Jackson, Patchwork Girl by Mary/Shelley and Herself (A Graveyard, A Journal, A Quilt, A Story, & Broken Accents) (Cambridge: Eastgate Systems, 1995), environment: Storyspace.

- Anne Balsamo, Technologies of the Gendered Body: Reading Cyborg Women (Durham: Duke, 1996).

- Nelson, Dream Machines, p. 75.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 78.

- Ibid., p. 68.

- Ibid., p. 74.

Daniel Rosenberg is assistant professor of history in the Robert D. Clark Honors College at the University of Oregon. His next book concerns the history of the past.