Thing / No. 2

Three reports

Paul Maliszewski, R. K. Scher, and Mary Walling Blackburn

“Thing” is a column in which writers in various fields identify and describe a single found object not recognizable to the editors of Cabinet.

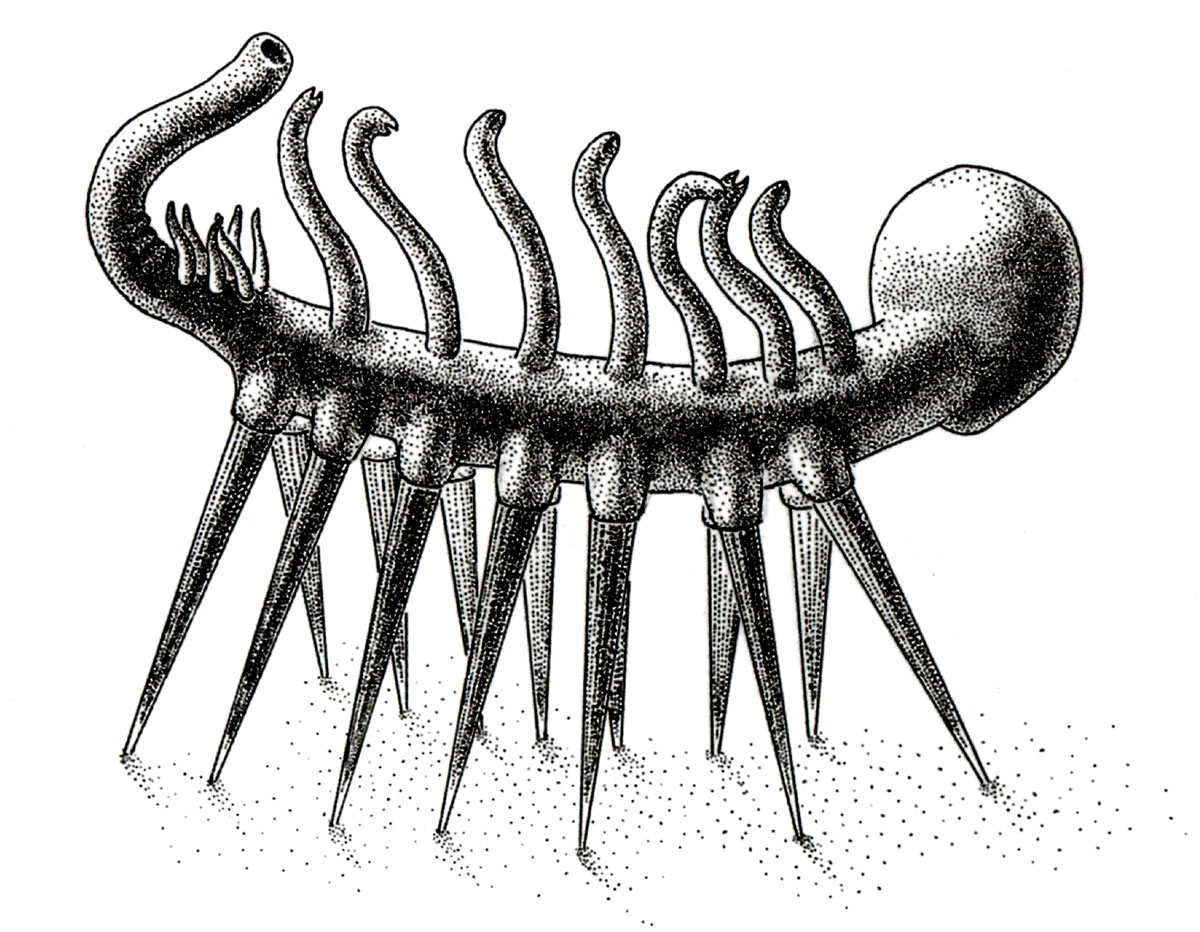

A few weeks ago, we got a letter from Kris Lee, Cabinet reader and occasional contributor. Lee, currently traveling through Uruguay, was going through a pile of prints at a second-hand bookstore in Montevideo and came across the strange image reproduced below. Unsure of its origins, Lee submitted it for this column and we, in turn, passed it along to three writers whose verdicts on the identity of the creature follow.

Kricorian’s worm (Lumbricus kricorian) was discovered by Josephine Kricorian on the island of Mauritius (20º S., 57.5º E.), on 14 July 1885. Kricorian, who studied kelp, collecting samples from seven oceans and eight seas over thirteen years, came upon the worm by accident. It was the morning, five or half-past. The other researchers, colleagues one supposes, were sleeping. The night before there had been a storm. Winds out of the southwest blew sand into Kricorian’s face as she stooped to retrieve a strand of Laminaria longicruris. She noticed the creature—she called it that at the time—attached, or clinging rather, to the frond’s underside. She dropped both in her specimen bucket, thinking the worm odd but not, as she later told the Times (of London), “so unusual as to halt my work.”

Kricorian’s worm ambulates on its 14 appendages, which terminate in a chitinous material not unlike a bull’s horn. In its natural habitat, at the bottom of the ocean, the worms lie on their backs, dug into the seabed and anchored with their major and minor stationary trunks. The worm’s mouth, or feeding tube, functions separately from its face, distinguishing it from every known organism. An anchored worm draws prey near with its face, a highly attractive and malleable muscle able to mimic other organisms. As the face works its dark art, the appendages grip the prey—small fish, typically—and then pass it along, as friends seated at a Japanese restaurant might pass pieces of pickled ginger. The last pair of appendages lowers the fish into the feeding tube. Some worms have measured one meter in length, end to end. The feeding tube whistles when the worm is distressed, but its face, which is beautiful, maintains a peaceful look, as if it were thinking, “Look upon me. Look upon me. Look upon me, you fool.”

—Paul Maliszewski

• • •

This is not the small creature it appears to be. It’s colossal, a beast. Its face has never been seen. Worst of all, it is not alone. There are many of its kind.

These monsters prey on the weak, sucking the many into their many mouths, always more mouths, as many as there are many. We weak ones, do we run when we see the beast coming? Yes, but not away. We run toward it if we can; if not, we crawl. We believe the beast will care for us. So we go gladly, we apply, we stand in line, we wait on hold. After all, we have been paying the beast for years. Carefully laying down our earnings for spearing by the beast’s spiky, collecting legs. It’s all according to plan; the payments, the devouring. But the payoff never comes. It’s nothing but digestive juices and bankruptcy.

One day the right advocate will come, the beast’s destiny, its sworded saint. The legend says that an exterminator will come who knows the signal the beast cannot resist. It isn’t money, not sex (the beast is self-fulfilling), not movie deals or drugs. Something, one thing only, will make it turn its face. A mirror, a soft spot, a plea bargain: its face revealed, its name made plain (these rules don’t change), its poor grammar corrected ... it will expire. And we will be free, fully uninsured at last.

—R. K. Scher

• • •

While living in New Mexico, I came across a glass display case at the university’s medical library that contained ephemera from the tuberculosis retreats located in the surrounding desert in the 1920s. One panel documented a longer history of TB treatments within the greater US and included a fragile drawing made by a Kentucky TB patient that pictured something uncannily similar to the creature in question. The text read:

Prepared for the Speleological Oral History Record in April of 1912 by Phineas Hamil of the Kentucky State Cave Society

In a more southernly county of Kentucky—before the Civil War—Stephen Bishop, a slave speleologist, of African and white descent, dunked his hands in a sluggish and warm underground stream located within the cave that he regularly described as “grand, gloomy, and peculiar” to the tour groups he led for his master. When his hands emerged from the stream, he held within them a small, blind, luminescent creature from the phylum arthropoda. This freshwater troglodyte was the size of his fingernail. Stephen Bishop knew everything about these caverns—the fugitive slaves who took shelter underground before they continued northward, the paleo-Indian mummies, the slender glass lizards, the pistol-grip mussels, the black gypsum deposits. However, he was not familiar with this animal. It was laterally compressed—not unlike whale lice or skeleton shrimp—and when he cracked open its legs they were hollow; its body cavity was an open space where tissue, sinuses, and blood loosely floated.

Several years later, Dr. John Croghin, the new owner of the cave and of Stephen Bishop, had twelve wood-and-stone huts built within the cavern because he believed that the perpetually cool and humid air would heal the botched lungs of tuberculosis patients. Several died, the rest fled to drier climes, but one remained long enough to draw the only extant drawing of Stephen Bishop’s Troglodyte. The last specimen was found that year of experimental cavern treatment, in a silty pond not far from the huts. The creature was hardly breathing and it could not stand the weakest light, averting its so-called face (which was translucent and smooth, save an orifice for eating) from the candle’s flame. Underneath the drawing, the artist-cum-tubercular patient inscribed in careful cursive: Croghin’s Troglodyte. Despite Stephen Bishop’s eventual manumission and the departure of other freed slaves in the county to Liberia, he stayed behind and died there.

—Mary Walling Blackburn

If, in your travels, you should happen to come across a curious Thing of your own, please send a picture of It to us digitally (via this email [link defunct—Eds.]) or through standard mail (mailing information here). We will consider using it for a future column.

Paul Maliszewski recently edited Paper Placemats (J&L Books) and two issues of Denver Quarterly. His writing has appeared in Harper’s and The Paris Review.

R.K. Scher is a writer living in New York whose hobbies include insurance reform advocacy.

Mary Walling Blackburn curates the “War and Empire Summer Drawing Lyceum” and the “Humility Lecture Series.” She has recently been selected for the Emerging Artists Show at HereArt in Manhattan. This fall, Women and Performance: Journal of Feminist Theory will publish her essay on photographing nuclear craters in the American West. She lives in Brooklyn, New York.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.