Fluid States

The maritime in modernity

Margaret Cohen

The natural element for industry, animating its outward movement, is the sea. Since the passion for gain involves risk, industry though bent on gain yet lifts itself above it; instead of remaining rooted to the soil and the limited circle of civil life with its pleasures and desires, it embraces the

element of flux, danger, and destruction. Further, the sea is the greatest means of communication, and trade by sea creates commercial connections between distant countries and so relations involving contractual rights. At the same time, commerce of this kind is the most potent instrument of culture, and through it trade acquires its significance in the history of the world.

—G. W. F. Hegel, Philosophy of Right

From the mid-nineteenth through the end of the twentieth century, the great cultural theorists delineated a geography of modernity that was primarily land-based. The focus of Marx, Benjamin, or Foucault on terra firma, on territorialized spaces like the nation state, the city, the colony, the home, and the factory, would have surprised Hegel and, indeed, his early-modern predecessors, who lived with a keen awareness of the waterways of global capitalism. Today the history of cross-ocean travel is once more spilling over from the specialized purview of maritime historians and sailors. While narratives of human struggles with the sea’s most inhospitable waters, like Nathaniel Philbrick’s In the Heart of the Sea, Alfred Lansing’s Shackleton, and Tony Horwitz’s Blue Latitudes, attract a general public, scholars in the university are organizing the regions of the world’s oceans into new interdisciplinary paradigms such as Atlantic Studies or the recent Oceans Connect project at Duke University.

Benjamin famously observed that history is a constellation the present makes with the past. His dictum explains the current shift from what might be called a solid to a fluid worldview. As we witness globalization developing to a new level in tandem with new technologies, we are once again able to recall the sea as a frontier zone from the turn of the sixteenth century to the end of the nineteenth century. Let two examples indicate convergences that are too extensive to develop here. As Hegel declares above, “the sea is the greatest means of communication,” making it the Internet of its time. Or compare today’s concerns over terrorists to the threat of piracy in the early modern era. Further, regulating safety and commerce across the ocean’s non-national spaces spurred the development of international law, whose founding text dates back to Grotius’s Freedom of the Seas (1609).

The sea’s impact on global capitalism is not only a matter of historical record. Currently, 96 percent of the world’s freight measured in terms of weight travels by sea, and the figure is increasing with the growth of international trade. Among cultural critics, the writer and photographer Alan Sekula has perhaps done the most to make visible the human face of the contemporary maritime world. The machinery in his image of Long Beach, California from Fish Story, 1993, resembles the immense cranes of the Port of Oakland at the gateway to the San Francisco Bay Area, where I live. Written in the shadow of these cranes, this essay delineates concepts at the intersection of modernity’s epistemology and aesthetics that take on particular clarity from the perspective of the maritime world. These concepts are 1) “craft,” a hands-on, innovative practical reason that is distinct from the conceptual knowledge of philosophers and the systematic, rationalized knowledge of the scientist; 2) “the edge,” an uneven and complex zone where craft flourishes at the limit of not only European culture and knowledge, but culture and nature; 3) “the glow and the haze,” in the words of Joseph Conrad: a distinctive phenomenoloigcal blur encountered in the edge zone that complicates the classic Western opposition between the light of knowledge and the darkness of error and that is essential to the full deployment of craft.

Before 10 oClock we had 20 and 21 fathom and continued in that depth until a few Minutes before a 11 when we had 17 and before the Man at the lead could heave another cast the Ship Struck and stuck fast. Emmidiatly upon this we took in all our sails hoisted out the boats and sounded round the Ship, and found that we had got upon the SE edge of a reef of Coral rocks having in some places round the Ship 3 and 4 fathom water and in other places not quite as many feet.

Cook then details a bravura rescue of his ship and men that justifies the Admiralty’s confidence in this self-taught mariner of humble origins who worked his way from sailing on coal ships in the North Atlantic to fame. In this rescue, Cook evinces an extraordinary practical capacity, one that the philosopher Gilbert Ryle isolates as a specific—and often neglected—form of knowledge: “knowing how” (in contrast with “knowing that,” the knowledge of philosophers and scientists). The association of “knowing how” with the mariner has a long history reaching back to the dawn of Western culture and Odysseus, who is said to be the first sailor to have steered by the stars. The Greek word for Odyssean cunning is metis, the same word that gives French the root of métier, as in arts et métiers, arts and crafts. As Jean-Pierre Vernant and Marcel Détienne have observed in Cunning Intelligence in Greek Society, metis requires finding a path (poros) through the impasse (aporia), which makes Odysseus navigating between Scylla and Charybdis a forerunner of Captain Cook on the Great Barrier Reef. In Dialectic of Enlightenment, Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer cast Odysseus as the harbinger of Enlightenment, which they understand as a project of domination, arguing that Odysseus dominates nature by undoing its enchantments. But from the maritime perspective, it becomes clear that while metis can of course abet domination, its specificity is rather to outsmart superior forces that cannot be subdued.

In Cook’s escape from the Great Barrier Reef, know-how is shown to be at once a matter of knowledge, intelligence, and character. Cook’s first steps follow an accepted protocol for running aground, one based in the collective wisdom of a body of skilled sailors. First, he rounds the ship in a long boat and takes stock of the damage, then he starts the pumps, lightens the ship by jettisoning everything that can be done without, and waits for high tide. After the first high tide fails to free the Endeavour, Cook shows stubborn patience, sitting through another tidal cycle in this unknown region in the hopes it may prove higher, which in fact turns out to be the case. But with this higher tide comes an increased flow of water into the gash cut through the hull by the razor edge of coral. The Endeavour’s company finds itself, in Cook’s words, in “alarming and I may say terrible circumstance.” The leak “threatened immediate destruction to us as soon as the Ship was afloat.” Since the alternative is certain death, Cook then resolves “to resk all and heave her off in case it was practical”—demonstrating an audacity that is as integral to his skill at navigation and command as patience and collective wisdom. Throughout this desperate situation, Cook’s chief naturalist Joseph Banks observed, Cook, like his crew, maintained a “cool” and “cheerful” attitude. This optimism of the will despite pessimism about outcome is another distinctive feature of knowing how.

Once the ship is floating freely, the leak threatens, as Cook feared, to swamp the ship. Taking basic materials at his disposal, Cook ingeniously refunctions them in response to hitherto unimagined circumstances. He recalls a technique called “fothering,” whereby “we Mix ockam & wool together ... and chop it up small and than stick it loosly by handfuls all over the sail and throw over it sheeps dung or other filth. Horse dung for this purpose is the best. The sail thus prepared is hauld under the Ships bottom by ropes ... while the sail is under the Ship the ockam &c * is washed off and part of it is carried along with the water into the leak and in part stops up the hole.” With these humble materials, soldered by ingenuity, Cook is able to maneuver his craft and crew safely to shore, where he can undertake more exacting repairs. When Joseph Conrad looked back on the heroic age of sail in The Mirror of the Sea, he designated such an effective, inventive capacity as “craft.” This beautifully chosen word connotes at once technical skill refined by the wisdom of a collective; the art, rather than the science, of practice (think of the craft of the poet, or the statesman); the cunning that makes the art more than technique (“cunning” even has a specific maritime meaning: to cun is to steer a ship); and even the water-borne vessel itself.

The mariner’s craft is fully embodied by exceptional individuals like Cook, and yet even these exceptional individuals rely on a crew of sailors with various specializations to execute their maneuvers. The mariner’s craft thus has an intrinsic collective dimension that undergirds even the official account of Cook’s voyage itself. The apparent first-person narration was in fact produced from a range of sources, including Cook’s logs and those of others on his expedition—all sutured together by John Hawkesworth, a professional writer hired by the Admiralty. As it turned out, Cook was not happy with the result, and revised his journals for publication himself. His revisions nonetheless share with Hawkesworth’s version what became known by the seventeenth century as “plain style,” which sealed a book’s salt-water authenticity. Plain style is the literary expression of craft, and Cook’s idiosyncratic spelling is of a piece with its terse, utilitarian, informational narration, specialized vocabulary of work, lack of figuration, down-to-earth if not crude subject matter, and understated affect. Ernest Hemingway, himself a teller of fish stories, praised and practiced something like plain style, which he derived from the imperatives of journalism. Hemingway’s grace under pressure resembles the cool of the master mariner, but his heroes are the dandies of craft: what matters for mariners like Cook is not grace, but effective performance. For Conrad, however, who explicitly likened work on “deck” to the writer’s work “at the desk,” effective performance passed from “skill ... into art,” when it entailed innovation, making craft the honor of all those workers who “by ceaseless striving raise the dead-level of correct practice in the crafts of land and sea.”

Conrad called craft “the honor of labor,” making this quality the underpinning of a value system founded on work. But craft is an ethos without ethics, one that is results-oriented, focused on survival and potential profit. The utilitarian dimension to craft is distinctly modern, in contrast with the feudal ethos of Odysseus, who focused on homecoming and the restoration of his kingdom. Another modern aspect of craft is its association with strictly human agency, whereas metis was a quality humans shared with gods and the crafty denizens of nature in the enchanted cosmos of antiquity. In narratives of exploration across the heroic age of sail, salvation is increasingly offered not by divine providence but via the mariner’s agency. Robinson Crusoe is the watershed in this shift from providential to secular narratives of survival, though it uneasily seeks to reconcile the two. By the time of Cook’s journals, the divine will have receded almost completely, and the craftsman will reign.

Outlaw culture thrived on the unpredictability and unevenness of life “beyond the line,” in the early modern phrase preserved by Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker in The Many-Headed Hydra, where they celebrate the edge zone’s possibilities for creative self-invention. Life beyond the line ranged from experiments in social equality to sheer brutality. In the General History of the Pyrates (1724), a collection of rogues’ biographies that scholars now believe to have been written at least in part by Daniel Defoe, the cross-dressing bisexual female pirates Anne Bonny and Mary Read carve out a temporary respite from sexual inequality, while the idealistic Captain Misson creates a proto-socialist society of absolute equality beyond private property. The brutal Blackbeard, in contrast, regresses to the world before the social contract, exercising his natural right to take whatever tempts him.

The edge zone of the maritime world underscores a critical feature of modernity: a fascination with risk that cannot be explained only in terms of profit and instrumental reason. While long-term hopes for profit drove exploration of uncharted waters, the short-term yield was often loss, if not death. But the edge zone’s powers of destruction did not discourage exploration. The edge makes apparent the extent to which novelty, that cardinal value of modernity, entails risk, danger, and violence. Baudelaire eloquently captured this face of novelty in Le Voyage, where travelers yearn to journey to “heaven or hell, what does it matter,” “to the depths of the unknown ... to find the new!”

Defoe called the assumption of risk epitomized in overseas adventuring “the projecting spirit” and linked it with profit-oriented ventures whose success was just plausible enough to warrant pursuit. As Defoe put it:

“Nothing’s so partial as the laws of fate Erecting blockheads to suppress the great. Sir Francis Drake the Spanish plate-fleet won; He had been a pirate if he had got none. ... Endeavour bears a value more or less, Just as ‘tis recommended by success.”

The name of Cook’s first ship, Endeavour, registers his projecting spirit, as do those of his ships on subsequent voyages: Adventure, Resolution, and Discovery. In the twentieth century, the edge has been pushed to outer space. The logo for Apollo 12 explicitly links the exploration of the moon to the heroic age of sail, representing the Yankee clipper “Intrepid,” whose name NASA took for its pioneer ing space craft. If the edge is still alive on earth, it is only recreationally—in the exploration of “extreme” places pursued by climbers, sailors, and divers. Here, the projecting spirit seeks not profit, but existentialist confrontation with survival.

The journey to the edge always has one yield, of course, which is knowledge: with the proviso that someone returns to tell the tale. The survivor’s narrative—what sailors call a “yarn”—thus plays a central role in adventuring at the maritime edge, a point not lost on Coleridge, Melville, or Conrad. The sensational nature of this survival contributes to the narratives’ appeal, which has historically been remarkable. In the early eighteenth century, for instance, at the time Defoe was writing, overseas travel literature is estimated to have outstripped even devotional literature in popularity. One staple of maritime travel literature was the shipwreck narrative, where disaster ensued in the wake of storm, naval defeat, mutiny, or piracy. The tradition began almost 300 years before Robinson Crusoe, when writers recounted the sufferings of Portuguese traders returning from India, who loaded their vessels beyond capacity and shipwrecked off the East African coast. Bereft of the tools and structures of civilization, castaways confront the challenges of survival at the elemental level of the body, subject to threats ranging from cold and starvation to cannibals. In the edge zones, where survival is always at issue, the crafty thrive.

During the early modern era, due to the imperfect state of navigational technologies, educated guesswork was the condition of all seafaring once out of sight of land. From the late medieval period, mariners could pinpoint latitude by noting the angle of heavenly bodies relative to the horizon. But for the first three hundred years of open ocean travel, there was no way to measure a ship’s longitude while at sea. The most efficient means would have been to measure the differential in the hour of day at the current position against the same hour at the prime meridian; however, across the early modern period, no clock remained accurate over a long sea voyage. Since even a hundred yards could mean the difference between safety and a deadly shoal, a sound way to measure longitude became a holy grail of early modern technology and science, as Dava Sobel has detailed in her Illustrated History of the Longitude.

Until such a means of measurement was devised, mariners had no choice but to practice “reckoning” based on “conjecture.” The ability to navigate with partial knowledge distinguishes the craft of the master mariner. William Dampier, who circumnavigated the globe three times at the end of the seventeenth century, recounts finding his position one dark night when he heard the sound of turtles swimming and realized he was on the route of their seasonal migration. Once the problem of longitude was solved with clockmaker John Harrison’s invention of a reliable chronometer in 1759, however, craft was replaced by science. Conrad laments the loss, with the advent of science, of what he calls “incertitude,” which fosters craft, when he suggests that steam travel destroyed the mariner’s know-how. In Conrad’s words: “the taking of a modern steamship about the world ... is a less personal and a more exact calling; its effects are measured exactly in time and space ... the incertitude which attends closely every artistic endeavor is absent from its regulated enterprise.”

Craft participates in modernity’s temporality of innovation and supercession. As Conrad puts it, “the special call of an art which has passed away is never reproduced. It is as utterly gone out of the world as the song of a destroyed wild bird.” Or perhaps it passes from craft to art. For Conrad the writer (Conrad at the “desk,” rather than on “deck,” to reprise his terms), the great obscurity to be navigated is not terrestrial position, but rather the meaning of words. Uncertainty becomes an intrinsic feature of Marlowe’s yarns, which relate how European men engage in incomprehensible acts in the historical edge zones of European conquest, like Kurtz in Heart of Darkness or another James, the protagonist in Lord Jim. In describing Marlowe’s yarns, Conrad expresses their obscurity as an atmospheric effect. Their meaning, he writes, is “not inside like a kernel but outside, enveloping the tale which brought it out only as a glow brings out a haze, in the likeness of one of these misty halos that sometimes are made visible by the spectral illumination of moonshine.”

In its constitutive obscurity, Marlowe’s narrative style epitomizes the modern sublime. “To make anything very terrible, obscurity seems in general to be necessary,” Edmund Burke wrote in his Philosophical Enquiry into the Origins of the Beautiful and the Sublime, adding that “when we know the full extent of any danger, when we can accustom our eyes to it, a great deal of the apprehension vanishes.” Obscurity for Burke has two aspects: the epistemological uncertainty that helps cause the breakdown of reason, and the aesthetic effect that the artist or writer uses to summon up this experience for the spectator, and hence transform its destructive power into art. The sea figures prominently in sublime depictions across the later eighteenth and nineteenth century, which is to say precisely the era that sees the routinization of seafaring due to scientific advances. It is worth asking whether the sea becomes available as sublime subject matter because it no longer poses an immediate practical challenge. Certainly, these sublime depictions contrast sharply with early modern imagery of the sea, which offers a wealth of practical information on the kinds of ships, exploits, and métiers found in the maritime world.

For Romantics, the edge zones of human exploration, the mountains and sea, were certainly prime territories. The debt of writers like Coleridge and Edgar Allan Poe to the narratives of Captain Cook suggests a direct link between the epistemological obscurity of the maritime edge and the Romantic sublime. In art, the epistemological obscurity of the edge zone is first given aesthetic form by William Hodges, the artist on Cook’s second voyage. Hodges’s work was long appreciated primarily for its informational purpose, but is now finally receiving its artistic due in a career retrospective organized by the National Maritime Museum and traveling to the British Art Center at Yale in January 2005. An atmosphere of Conrad’s “glow and haze” pervades Hodges paintings celebrating Cook’s discoveries. In Cascade Cove, Dusky Bay, for instance, a bewitching shimmer emanates from this spectacular inland fjord, above all from the rainbow of color that bursts from the cascade.

Hodges’ sublime might seem to prefigure the work of Caspar David Friedrich, where spectators contemplate the hazy aspects of mountains, fog, clouds, and seas, as in his Monk by the Sea (1809–1810). But to compare Hodges and Friedrich is to notice that the sea in Friedrich’s rendition is strikingly empty of life; while Hodges presents the sea as a theater of work and survival. Put another way, Hodges calls attention to the fact that the glow and the haze is part of navigating the edge zones, an epistemological experience of those at sea, whereas Friedrich literally erases this connection. Indeed, contemporaries recount that Friedrich initially had two ships in Monk by the Sea, but painted them out in the final work to increase the scene’s feeling of desolation.

J. M. W. Turner took issue with Friedrich’s empty sea, a point he wittily makes in Sunrise with Sea Monsters, where he puts the spectators on land back in the water by making them a fantastic part of the scene, perhaps a phantasmatic illusion emanating from its hazy atmosphere. More seriously, Turner plunges the spectator into the phenomenology of being at sea in his Snowstorm—Steamboat off a Harbour’s Mouth Making Signals in Shallow Water, and Going by the Lead. The original title continues: The Author Was in this Storm on the Night the “Ariel” Left Harwich. Turner cultivated the myth that he was lashed to the mast so as to experience, yet survive, the full might of the gale. His evocation of Odysseus listening to the Sirens is in keeping with the transformation of metis into modern craft, for while Odysseus plumbed enchanted knowledge, Turner seeks to experience the violence of indifferent nature.

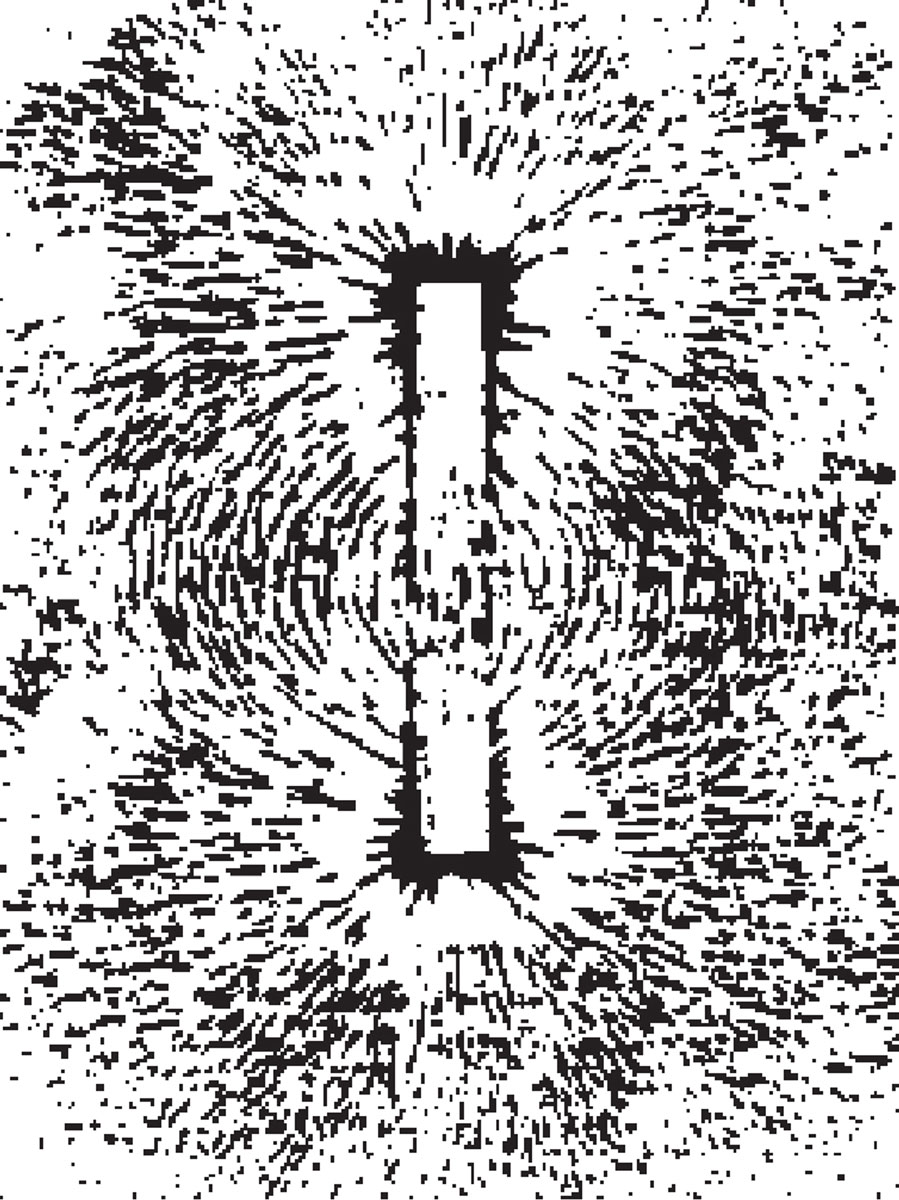

The disorientation of the snowstorm recalls the phenomenology of pitch and roll that attends life at sea. But beyond visual dislocation, Turner summons up the mariner’s craft through the swirling patterns of paint that express the violence of the weather. As James Hamilton observes in Turner and the Scientists, Turner based these patterns on the latest in scientific theory, the description of electromagnetic fields by Michael Faraday in his Experimental Researches in Electricity (1831). Patterning his storm after electromagnetic fields, Turner connects his artistic technique in rendering obscurity to the compass technology that catalyzes the history of modern navigation. With this maritime contextualization, Turner implies that the artist, too, is a craftsman skilled in the knowledge of a collective, wielding art as a technology to navigate partial knowledge. He thus opens lines of inquiry concerning the sublime other than the prevailing view that it is the heroic achievement of an individual genius who is able to rescue failed life with art. If the course of this essay has traveled from Captain Cook to Conrad to the foundational modern aesthetic of the sublime, it is to emphasize a version of Turner’s insight: While the history of seafaring might seem to be located “out there” on the periphery, it is in fact at the core of our cultural modernity.

Thanks to Mariano Siskind for the Hegel citation that opens this essay.

Margaret Cohen teaches French and comparative literature at Stanford University. She writes about the literature and culture of modernity, and is currently completing a book on The Novel and the Sea. Her most recent publication is a new Norton critical edition of Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.