Dead Seas

The psychogeography of Southern California

Mark Dery

For an extremely large percentage of the history of the world, there was no California. ... The continent ended far to the east, the continental shelf as well. Where California has come to be, there was only blue sea reaching down some miles to ocean-crustal rock, which was moving, as it does, into subduction zones waiting to be consumed.

—John McPhee, Assembling California [1]

I grew up in the Silurian age, in San Diego’s South Bay. Back then, what would ultimately be Southern California was part of Laurasia, the supercontinent formed when North America, Greenland, Europe, and most of Asia drifted together near the equator. Fish were evolving jaws and land flora was taking root in the form of vascular plants such as Rhyniophyta. Then, as now, in San Diego politics, invertebrates ruled.

Actually, I grew up in the 1970s, not 443–417 million years ago, but who’s counting? During the Santa Ana season of 1971, suburban Chula Vista sure as hell felt prehistoric to a sixth-grader like me. The pitiless sun hung in the sky like God’s magnifying glass, ready to incinerate any human insect foolish enough to wander outdoors. When the Santa Ana winds came, they rattled the dead fronds in the palm trees and whipped dust devils across the playground at Hilltop Elementary School, making a lonely noise in the chains of the empty swings. I divided my time between spontaneous nosebleeds, blackout-strength headaches, and the Paleozoic of the Mind. When I wasn’t sprawled on a rubber-sheeted cot in the nurse’s office, a wet paper towel clamped on my nose or clutched to my forehead in the best drama queen fashion, I was time-traveling through the pages of the Time-Life Nature Library book The Sea—specifically, through the two-page spread on pages 48–49, a prehistoric seascape by the Czech illustrator Zdenek Burian.

As the other students in Mr. Harris’s sixth-grade class drowsed over their library books, stuporous in the airless heat (air conditioning was nonexistent then, at least in our school), I snorkeled through Burian’s prehistoric ocean. Trilobites scooted across the ocean floor, whip-like antennae trailing behind them. A gastropod lay, half-buried, in the sand. Nautiloids—grotesque, squid-like creatures with popeyes and cone-shaped shells, some of which reached sixteen feet in length—scuttled along on writhing tentacles. Burian gave them glossy, brightly colored shells, tricked out in zany zigzags and vibrating pinstripes—a Silurian premonition of the hot rods native to the California of my day. The scene stretched into the distance, lost in hazy, submarine sunlight. Even the illustration’s caption, written in the lyric mode of one of those voiceovers from The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau, inspired poetic reveries: “The sea bed bloomed with tufts and huge honeycombed colonies of corals. Sea lilies tossed their heads in the ancient currents.”[2] Lost in the shadow-dappled scene, I felt deliciously cool, weightless, and carefree in a time before time.

To me, Burian’s painting of a Silurian seabed was a poor man’s Atavachron, the time machine in the old Star Trek episode “All Our Yesterdays” that enabled the inhabitants of a doomed planet to escape into the past before their sun exploded. Indeed, during the weather phenomenon from Hell that meteorologists call a katabatic wind and Southern Californians know as a Santa Ana, the sun seems as if it’s about to go nova. Anytime between October and January, the prevailing cool breezes, which blow eastward off the Pacific, can give way to scalding winds from the east—winds that blow in from the high desert plateaus north and east of Los Angeles and San Diego.

As Joan Didion has noted, the “devil wind,” as Spanish settlers of Alta California called it, shapes SoCal psychology. “Los Angeles weather is the weather of catastrophe, of apocalypse, and, just as the reliably long and bitter winters of New England determine the way life is lived there, so the violence and the unpredictability of the Santa Ana affect the entire quality of life in Los Angeles, accentuate its impermanence, its unreliability,” she writes, in the essay that has become the locus classicus for any discussion of strange weather and mass psychology in Southern California. “The winds show us how close to the edge we are.”[3]

Even in sunny, surfer-dude San Diego, a whiff of apocalypse hangs in the burning air on Santa Ana days. During one Santa Ana-season wildfire, when I was a kid, soot and smoke turned day to night and ash drifted dreamily from the darkened sky, the closest San Diego would ever get to snowfall. The heat was unreal, a blast-furnace wave. Soon, a cloud of locusts fleeing the inland fires arrived—huge, heavy metal insects straight out of a sci-fi movie about the end of the world. Whacking into the big glass pane of our patio door with an audible thud, they fell to the ground, dead. The next morning our cat ate her fill from the carcasses that littered the patio, leaving only their bony hindlegs.

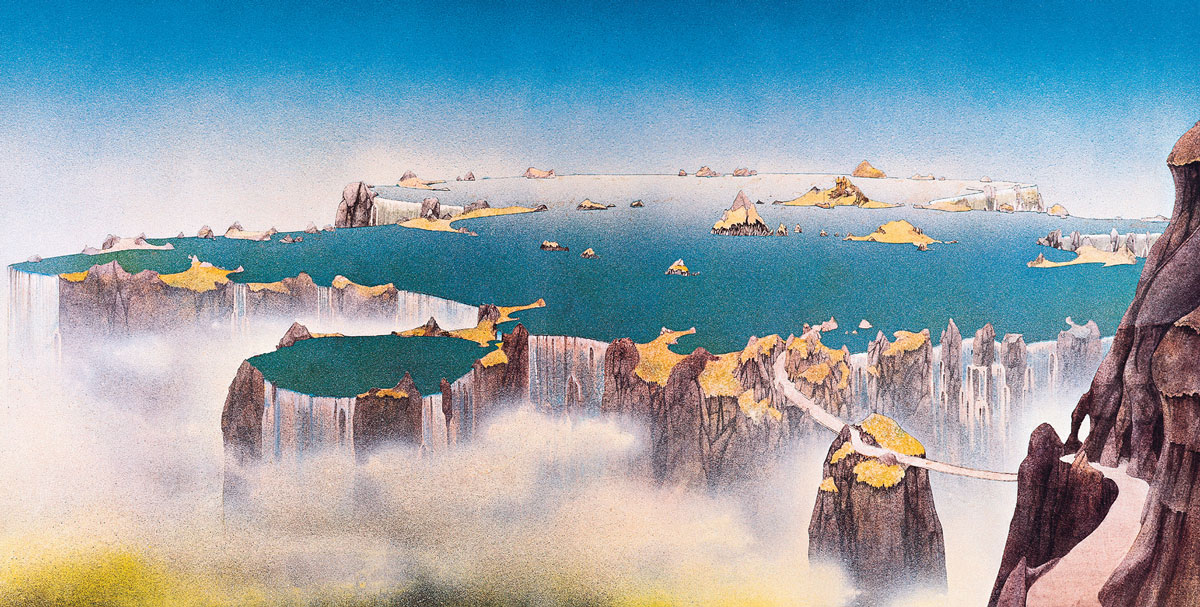

When your everyday world looks like a scene from Revelation, as directed by Irwin Allen, even a picture of cool waters, in a kids’ science book, can offer shelter from the infernal heat. Better still were album covers, which along with M. C. Escher calendars and black-light posters were the virtual reality of the pre-PC era. Incredible though it seems now, most kids I knew could spend an entire afternoon lost in the whoa-dude special effects and pothead surrealism of the British design group Hipgnosis (Led Zeppelin’s Houses of the Holy, Genesis’s The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway, Pink Floyd’s Wish You Were Here). But in my circle of shag-haired, waffle stompered friends, nothing spelled relief, when the mercury hit a hundred (or when we simply needed to escape the brain-numbing lameness of suburban SoCal), like Roger Dean’s trippy dreamscapes, many of them done for the prog-rock group Yes.

To be sure, Yes singer Jon Anderson’s gloopy, syntax-challenged lyrics helped fans beam into Dean’s imaginary worlds. In the 1970s, mulletheads everywhere broke up into discussion groups after a few bong hits, flaunting their hermeneutic chops with close readings of such Anderson howlers as, “A seasoned witch could call you from the depths of your disgrace / And rearrange your liver to the solid mental grace.”[4]

Amazingly, though, lyrics like “mountains come out of the sky and they stand there” or “river running right on over my head” make perfect sense when you’re staring at one of Dean’s lushly beautiful alien landscapes, where mammoth boulders float in mid-air and waterfalls come from nowhere and cascade into mist-veiled infinity.[5]

In Dean’s floating worlds, mountains really do “come out of the sky and … stand there.” Inspired by the Chinese landscape painting he encountered in Hong Kong as a teenage boy when his father was stationed there with the British army, Dean’s monolithic crags drift in fog oceans, ribboned with cliff-hugging trails. Sometimes, a tuft of moss (from the moss gardens Dean loved to make as a child) or a gnarled, wind-bent tree (typically a pine drawn from life, a Monterey cypress from Point Lobos on California’s central coast, or a Scots pine from Ashdown Forest, near the artist’s home) clings to Dean’s mountainsides. But his landscapes are at heart geological fantasias, empty of human or animal life (other than a distantly circling bird of prey or perhaps a lizard basking in the sun).

The mute, motionless actors in these frozen dramas are stones and rock formations, quarried from memories of actual places: in England, where Dean lives, the dolmens of Stonehenge, the rock-circles at Avebury, and natural formations such as the toadstool-shaped Brimham Rocks in Yorkshire and the massive, teetering Logan Rock in Treen; in the American West, where he has traveled widely, the fractured headlands that stagger into the sea at Point Lobos; Death Valley; and the primeval surrealism of Vermillion Cliffs and Arches National Monument and Bryce Canyon in Utah, whose hoodoos—limestone, siltstone, and dolomite sculpted by erosion into gothic spires, flying buttresses, and balancing boulders straight out of Chuck Jones’s Roadrunner—are archetypical Dean in the same way that the bizarre rock formations at Cape Creus, on the Catalonian coastline, are quintessential Dali.

In his autohagiography, The Secret Life of Salvador Dali, the painter rhapsodizes about the spot where “the Pyrenees come down into the sea, in a grandiose geological delirium.”[6] Gnawed by centuries of wind, rain, and seawater into suggestive shapes the locals have dubbed “The Rhinoceros,” “The Monk,” “The Camel,” “The Dead Women,” and so on, these hunks of mica schist are the inspiration not only for such, er, seminal works as The Great Masturbator but for the “morphological aesthetics of the soft and the hard” embodied in all those soft watches and lobster telephones.[7] According to Dali biographer Ian Gibson, one writer concluded, on visiting Cape Creus, “that Dali could only be fully understood if one took into account this extraordinary landscape that had shaped his thinking.”[8]

An instructive phrase: “That had shaped his thinking.” It makes us wonder: Which came first, the neurotic or the rocks? Do landscapes touch off sympathetic vibrations inside us because they resonate with childhood experiences, remembered or not? Dali once observed that his “mental landscape” resembled “the protean and fantastic rocks of Cape Creus.”[9] Did the vaginal clefts, phallic spurs, and fecal blobs of its tortured, metamorphic rocks mirror his sexual psyche, a battleground of (barely) repressed homosexuality, ravenous orality, and shameful anality? Or was Dali, in some weird way, shaped by the landscape he grew up in? The Situationists coined the term “psychogeography” to describe “the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals.”[10] Is there a psycho-geology—a study of the psychological effects of the rock formations we grew up around? Are there igneous, sedimentary, and metamorphic personalities? Is there a stratigraphy of the soul, a petrology of the psyche?

Tales from Topographic Oceans convinced me there is. At least, its cover art did. Tales itself was another story. A gesamtkunstwhatever based on the shastric scriptures, Tales was supposed to be the coolest thing to hit cosmic consciousness since sliced ectoplasm. As it turned out, critics (and some apostate fans) reviled the two-record epic for its poker-faced self-importance and pomp-rock flatulence. Spinal Tap avant la lettre, it turned progheads into cultural lepers and helped trigger punk’s primitivist backlash.

Even so, suffering through Anderson’s twee vocals warbling about “The Revealing Science Of God” was a small price to pay for Dean’s cover art, a glorious diptych depicting an unearthly landscape that is equally submarine and extraterrestrial, familiar and alien. In the moonlight, ancient stones brood over a fossil sea. It’s a desert, yet a school of salmon swims by, in the air. On the horizon, one of Chichen Itza’s temples is visible. The cryptic markings from the plains of Nazca can just be made out in the desert (ocean?) sands, an airstrip for ancient astronauts. On an oven-hot Santa Ana afternoon, when the dead brown yard outside my bedroom window looked as if it might spontaneously burst into flames any minute, Dean’s Sea of Tranquility beckoned, an ancient ocean where fish swam in zero gravity.

Dean’s extraterrestrial waterworld soon replaced Burian’s painting of a Silurian sea, on Santa Ana days, as my preferred vehicle for escapist fantasies of a cooler world. Beyond its soothing blues and underwater scenery, Dean’s rock-studded landscape struck a responsive chord. In its own alien way, it looked like a superlunar San Diego. Its jumbled rocks were familiar from the chaparral country to the east, where the climbing slopes are studded with crazily cantilevered granite boulders. Further east, the Anza-Borrego desert offers even more Deanian vistas, littered with monumental stones and the alien architecture of rock formations such as the Piedras Grandes, near Dos Cabezas; the Elephant Knees in the Carrizo Badlands; or the crumbling dolomite outcrop of the Pinyon Mountains. Even the prehistoric vibe in Tales and other Dean paintings felt like home, reminiscent of San Diego landmarks like the Torrey Pines bluffs, where glaciation has exposed the forty-five-to-fifty-million-year-old strata in the sedimentary cliffs and erosion has sculpted their sandstone facades, in the words of the authors of Geology Underfoot in Southern California, into “rills and gullies, a miniature badlands.”[11]

Much of what is now San Diego was once under water, submerged in ancient ocean. On the coast, this makes sense, but further inland, where even the briefest droughts threaten to turn all those Astroturf-green lawns into the desert they once were, it seems incredible. Still, developers’ bulldozers turn up the tusks and jawbones of prehistoric whales and walruses, and fossil mollusks glint from the sandstone bluffs. Strange to stand in Anza-Borrego’s Hawk Canyon, amid the sedimentary cliffs or the fissured, gill-like mud ridges of Arroyo Tapiado, and know that, eons ago, many of the mudhills, mesas, badlands and braided gullies were submarine. “Tiled ridges devoid of plant life stand in the glaring sun today where 10 million years ago a teeming ocean reef attracted colonies of gulf oysters and colorful corals,” the naturalist Mark C. Jorgensen writes in “The Ancient Sediments,” his essay on the Anza-Borrego. “Schools of fish swarmed erratically in the warm water at the approach of marauding sharks.” Then, the “shallow sea world of reefs and coves gave way to uplifting plates of land. … Inlets became brackish and increasingly shallow. Evaporation took its toll on the inland seas, leaving behind heavy salts as thick deposits of gypsum. … Where once the waves of the Pacific lapped up on an exotic shore, now heat waves dance on fossil reefs.”[12]

During the Pliocene and Pleistocene epochs (5–1.8 million and 1.8 million–10,000 years ago, respectively), the periods best represented by the San Diego fossil record, the Chula Vista of my boyhood was home to ocean reefs as well. According to Tom Deméré, curator of paleontology at the San Diego Museum of Natural History, the area was crawling with mollusks. There were bony fishes, rays, sharks, warm-water walruses (!), and some weird variations on the baleen whale. Elephant-like animals called stegomastodons roamed the surrounding lands, as did ground sloths, saber-toothed cats, and, oddly, camels. They’re all part of the fossil record now, fragments of shell or bone waiting for the developer’s bulldozer.

And the bulldozers will come, just as surely as Judgment Day. In San Diego, as in the rest of Southern California, there is a crying need for affordable housing. In 2004, the median cost of a single-family house in San Diego county hit $565,030, a jaw-dropping increase of $152,700 in a single year.[13] At the moment, only 11 percent of San Diego county households make enough money (at least $131,740 a year) to qualify for a loan to buy such a home—a record drop of 10 percentage points from a mere year earlier, according to a report released by the California Association of Realtors.[14] Will those little plastic developers’ flags one day flap in the badlands of the Anza-Borrego, heralding the coming of some master-planned community?

“Suburban sprawl, is it natural?,” asks Deméré, with a shrug in his voice. “I guess in a way it is. As a species, we’ve tended to disperse. The nomadic lifestyle was necessary because of the seasonal depletion of resources by tribes or family groups. We evolved on this planet, [and] we have exploited it ever since the beginning. Just look at Easter Island [for an example of] what native populations can do to an ecosystem. They essentially denuded that tropical paradise, turned it into a place of nightmares for humans. And the Anasazi did the same thing to the Colorado plateau. So this is not unusual. We are part of nature; the question is, are we willing to accept the depleted natural world that we live in, because of our presence? I view us as part of a natural process, [though] not necessarily a good one. There are consequences to it, and the consequences are a reduced quality of life for us and the species we share the planet with.”

“A reduced quality of life” may be a masterpiece of understatement, if meteorological Jeremiahs are to be believed. Extreme weather events brought to you by global warming, such as the monsoons in July 2004 that left millions homeless in northeast India and Bangladesh, may be a premonition of biblical deluges to come. A 2003 report on abrupt climate change, prepared for the Pentagon by scenario experts (in consultation with climatologists), imagined a near future straight out of the disaster movie, The Day After Tomorrow:

By 2005, the climatic impact of the shift is felt more intensely in certain regions around the world. ... In 2007, a particularly severe storm causes the ocean to break through levees in the Netherlands, making a few key coastal cities such as The Hague unlivable. Failures of the delta island levees in the Sacramento River region in the Central Valley of California creates an inland sea and disrupts the aqueduct system transporting water from northern to southern California because salt water can no longer be kept out of the area during the dry season. ... Floating ice in the northern polar seas, which had already lost 40% of its mass from 1970 to 2003, is mostly gone during summer by 2010. As glacial ice melts, sea levels rise and as wintertime sea extent decreases, ocean waves increase in intensity, damaging coastal cities.[15]At the very least, sea levels along the California coast are likely to continue rising throughout the next century, according to a 2004 report prepared by the Union of Concerned Scientists.[16] They could rise at the usual historical rate of about seven inches a century or, depending on the climate model used, almost four times that fast.[17] A study published in a 2004 issue of the journal Science found that ice shelves in the West Antarctic are melting rapidly, causing mammoth glaciers to slide into the sea.[18] The Pine Island Glacier, for example, is thinning at a rate double that recorded in the 1990s. If the Ross Ice Shelf, one of the area’s biggest shelves, melted completely, sea levels could rise by sixteen feet.[19] According to the glaciologist Robert Thomas, this new evidence means that the current climatological prediction that global warming will cause global sea levels to rise ten to thirty-six inches by the year 2100 will have to be revised upward.[20]

Maybe not tomorrow, or the day after tomorrow, or a thousand tomorrows from now, but someday, surely, the waters will return. “People look upon the natural world as if all motions of the past had set the stage for us and were now frozen,” says Eldridge Moores, the tectonicist from the University of California at Davis who serves as John McPhee’s geological tour guide in his book Assembling California. “To imagine that turmoil is in the past and somehow we are now in a more stable time seems to be a psychological need.”[21] The polar caps will keep melting and the seas will keep rising, though how fast and how high nobody knows. In centuries (millennia?) to come, will the rising waters transform the topographic oceans of San Diego’s canyon country into the seafloor they once were?

Or will a mega-earthquake shear off a big chunk of California along one of the state’s various faultlines, the scenario favored (so to speak) by Kenneth Deffeyes, the geology professor who accompanies McPhee in Basin and Range? Most likely the rupture will happen along the Mendocino transform fault, Deffeyes believes, with maybe the Garlock Fault that runs east-west above Los Angeles as one side of the new crustal plate formed by such a cataclysmic quake. Or maybe the fracture will keep heading south, past LA and through the Mojave Desert and the Salton Sea to connect, finally, with the Pacific Plate in the Gulf of California. “You create a California plate,” says Deffeyes. “And the only question is: Is it this size, or the larger one? How much goes out to sea?”[22]

Cortez believed California was an island, a fable popularized by the Spanish writer Garci Ordonez de Montalvo in Las Sergas de Esplandian (The Exploits of Esplandian, ca. 1510). In his book, de Montalvo spins visions of a gilded island “at the right hand of the Indies,” inhabited by griffins and seafaring black Amazons, “robust of body, with strong and passionate hearts and great virtues.”[23] Though it is “one of the wildest in the world on account of the bold and craggy rocks,” de Montalvo wrote, the island “everywhere abounds with gold and precious stones.” He called this mythical island California, after its Amazonian queen, Califia, a buff beauty whose “majestic proportions” and “vigor of … womanhood” anticipate the Nautilized, surgically enhanced gym bunnies and Malibu Barbies of latter-day Cali.

If history bears out Deffeyes’s geological prophecy, the myth of the golden island may come true, any millennium now. “The Salton Sea and Death Valley are below sea level now, and the ocean would be there if it were not for pieces of this and that between,” Deffeyes tells McPhee. “California will be an island. It is just a matter of time.”[24] Stand, on some Santa Ana day, at the San Diego foothills of the San Ysidro mountains, looking west. Remind yourself that here, right where you’re standing, was once the Pliocene shoreline. Squint your eyes in the fireball sun. There, among the rippling heat waves: You can almost see Roger Dean’s fish, swimming in the air.

- John McPhee, Assembling California (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1993), p. 5.

- Leonard Engel and the Editors of Time-Life Books, eds., The Sea (New York: Time-Life Books, 1961), pp. 48–49.

- Joan Didion, “Los Angeles Notebook,” in Slouching Towards Bethlehem (New York: Dell Publishing Co., 1968), pp. 220–221. Yes, “The Solid Time of Change,” Close to the Edge (1972).

- Yes, “Roundabout,” Fragile (1972); Yes, ”Siberian Khatru,” Close to the Edge (1972).

- Salvador Dali, The Secret Life of Salvador Dali (London: Alkin Books, 1993), p. 304.

- Ibid.

- Ian Gibson, The Shameful Life of Salvador Dali (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1997), p. 580.

- Ibid., p. 71.

- Guy Debord, “Introduction to a critique of urban geography,” Les Lèvres Nues, no. 6 (1955), available at monoculartimes.co.uk/city-tours/psychogeography/urbangeography.shtml. Accessed 30 July 2012.

- Robert P. Sharp and Allen F. Glazner, Geology Underfoot in Southern California (Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Publishing Company, 1993), pp. 21–22.

- Mark C. Jorgensen, “The Ancient Sediments,” in Paul R. Johnson, ed., Anza-Borrego: Desert State Park (Borrego Springs, CA: Anza-Borrego Desert Natural History Association, 1982), pp. 49–51.

- Roger M. Showley, “Housing economists raise yellow flag over San Diego,” The San Diego Union-Tribune, 31 August 2004. Available at utsandiego.com/uniontrib/20040831/news_1b31housing.html [link defunct—Eds.]. Accessed 30 July 2012.

- Lori Weisberg, “Fewer can afford to buy home here,” The San Diego Union-Tribune, 9 July 2004. Available at http://www.utsandiego.com/uniontrib/20040709/news_1b9afford.html [link defunct—Eds.]. Accessed 30 July 2012.

- Peter Schwartz and Doug Randall, “An Abrupt Climate Change Scenario and Its Implications for United States National Security,” October 2003. Available at gbn.com/articles/pdfs/Abrupt%20Climate%20Change%20February%202004.pdf [link defunct—Eds.]. Accessed 30 July 2012.

- Union of Concerned Scientists, “Climate Change in California: Choosing Our Future.” Available at climatechoices.org/impacts_coasts/ [link defunct—Eds.]. Accessed 30 July 2012.

- Ibid.

- Stephen Leahy, “Glaciers Quicken Pace to Sea,” Wired News, 24 September 2004. Available at wired.com/science/discoveries/news/2004/09/65067. Accessed 30 July 2012.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Quoted in McPhee, Assembling California, p. 278.

- John McPhee, Basin and Range (New York: The Noonday Press, 1990), p. 214.

- William Bowen, “Origin of the Name ‘California,’” California Geographical Survey (a resource of the Department of Geography at California State University, Northridge). Available at goo.gl/1KFm8. Accessed 30 July 2012.

- McPhee, Basin and Range, p. 216.

Mark Dery is a cultural critic based in New York. He is the author of Escape Velocity: Cyberculture at the End of the Century (1996) and The Pyrotechnic Insanitarium: American Culture on the Brink (1999) and the editor of Flame Wars: The Discourse of Cyberculture (1993). He is the director of digital journalism at the Department of Journalism, New York University.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.