The Confetti of Empire

Nauru’s riches to rags story

Keller Easterling

Refugees, the human waste of the global frontier-land, are the “outsiders incarnate,” the absolute outsiders, outsiders everywhere and out of place everywhere except in the places that are themselves out of place—the “nowhere places”

that appear on no maps used by ordinary humans on their travels. Once outside, indefinitely outside, a secure fence with watching towers is the only contraption needed to

make the “indefiniteness” of the out-of-place hold forever.

—Zygmunt Bauman[1]

Maritime metaphors are favorites of both neoliberals and super-Marxists. The neoliberal portrays a globalizing frictionless sea in which virtual packets of information accomplish the goals of a one-world economy. For the super-Marxists, the sea is sometimes portrayed as the site of biopolitical groundswell, possessing the potential to utterly disrupt market forces. Meanwhile, the real sea is carrying 95% of the world’s goods and materializing the tonnage of trade. The real sea also sloshes up against gigantic new incarnations of the global city—specialized logistics enclaves, free trade zones, and export processing zones spreading over hundreds of kilometers of space. Most are in an offshore political quarantine, free from unions, strikes, taxes, and laws, free to leverage advantages in the differential values of labor and currency.

However immune to such administrative strictures, many of these conurbations land in the crosshairs of territorial conflict. Historically focused on landed properties, these conflicts now primarily concern waters and archipelagic networks of “offshore” activity where laws and jurisdictions collide. The United Nations’ new Laws of the Sea (1982) exacerbate this latent conflict by establishing, for any nation, an exclusive economic zone 200 nautical miles off their shore. For archipelagoes of the South China Sea, this new law creates not only many overlapping boundary lines, but a rush to lay ancient claim to islands or rocks that extend, for instance, national rights to fishing or offshore oil.[2] Indeed, given the movements of refugees and the increase of contemporary piracy, money sheltering, and ocean resource wars, the sea and its islands are not smooth and frictionless, but slushy and hard.

The troubled archipelagoes of the sea, which have historically been associated with escape, have become bellwethers of the world’s troubles. Islands are the world’s fabled storage places for cultural exceptions and secrets, the place of doppelgangers, other wives, confidence men, and pirates. Harboring alternative or multiple realities or the ingredients of culture that fall outside permissible boundaries, they are exempt from the laws that govern behavior on the continent. Consequently, they are often used as penal colonies or, during war, as stationary battleships or bomb-testing sites. Not only refugees and criminals, but also hidden business practices, tax exemption, streamlined paperwork, and cheap labor are exiled to or stored on islands. And as most of the world’s islands and atolls are sinking due to global warming, they also provide accelerated, amplified measure of the world’s environmental indiscretions and socio-economic fictions.

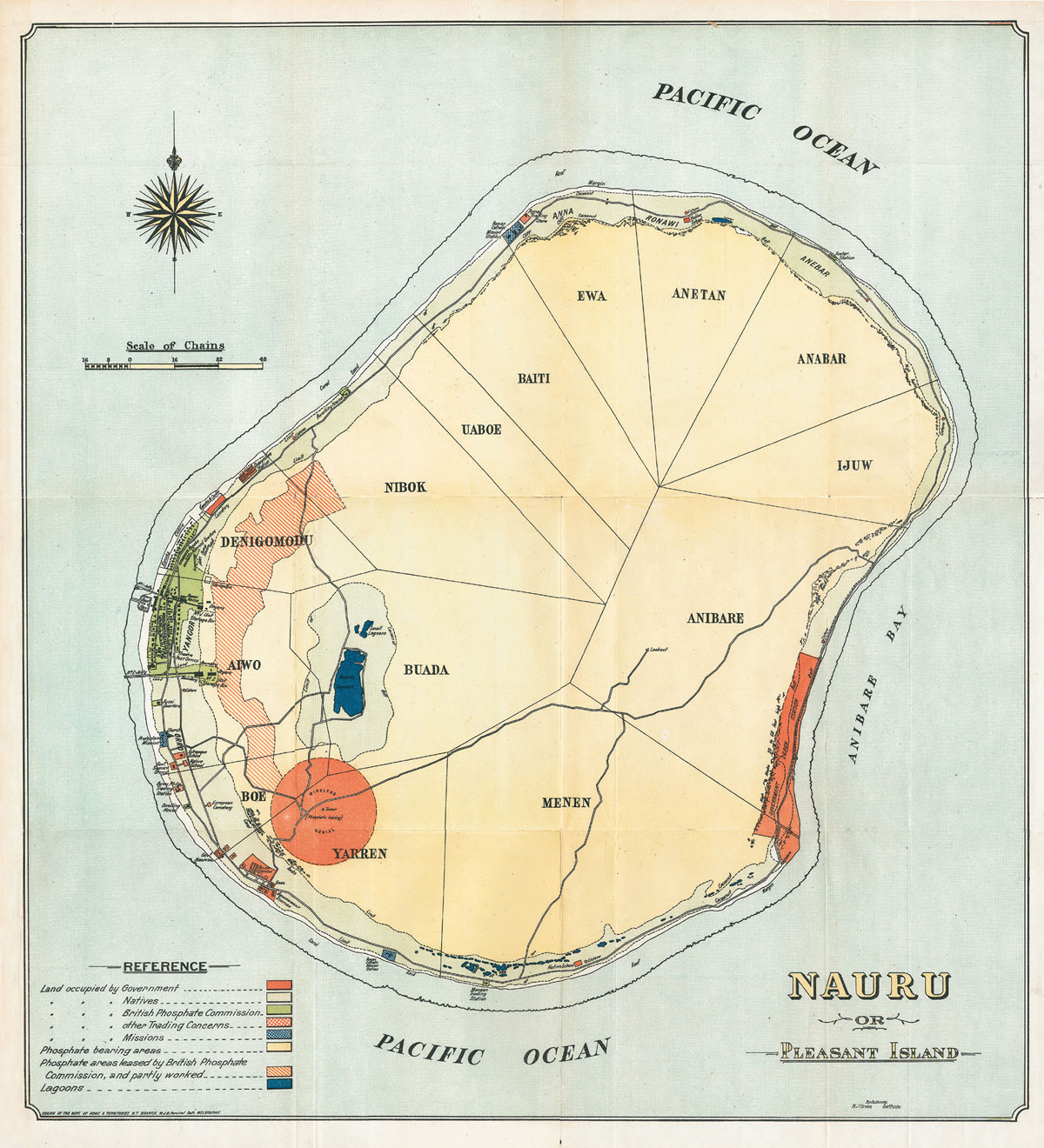

Nauru, located in Oceania just south of the Marshall Islands and north of Australia, is one such tiny spot on the globe. Surrounded by a vast ocean, the island of Nauru is the smallest republic in the world. With 12,000 people, it is about 8 square miles, or one tenth the size of Washington, D.C.[3] It achieved independence in 1968 and was only recognized by the United Nations in 1999, but in its short life it has managed to be the victim of or culprit in most of the familiar forms of economic, political, and environmental disaster.

Nauru’s story is one typical of islands that have served as the confetti of Empire. A European whaling ship captain discovered it in 1798. After guns were sold to the islanders by more passing Europeans, the 12 heretofore largely peaceful tribes there initiated a 10-year war. Germans then conquered the island in 1888. When phosphate was discovered there, a by-product of the guano produced by the huge numbers of birds such as noddy terns that populate the tiny island, Australian mining companies moved in to extract it, paying half a penny per ton to the Nauruians. The island was seized from the Germans and occupied by Australia during World War I; it was captured by the Japanese in 1945 and retaken by Australia that same year.[4] For the past 90 years, Nauru’s phosphate reserves have been mined to the point of exhaustion. As Nauruians were lured into questionable investment schemes, including a musical about Leonardo da Vinci’s love life, its economic reserves have also been fleeced.[5]

After the mines were spent, a period of what has been called “Gilbert and Sullivan” economics ensued as the country sampled every illegitimate means of making money.[6] However tiny, Nauru has the power to attach to everything, even the world’s superpowers, as a germ, thorn, or persistent irritant. Yet it also remains a sympathetic character given its previous years of exploitation. Nauru always needs to be saved, from others and from itself. It is both a place of extraction and a dumping ground for the world’s waste. Like a high-maintenance friend, the island is a tiny but infinite black hole for absorbing assistance and attention.

Kinza Clodumar, then President of the Republic of Nauru, gave a speech immediately prior to Vice President Al Gore at the Kyoto conference in 1997, asserting that the exhaustion of the phosphate mines and the denuding of the tropical forest were examples of Nauru’s exploitation by colonial powers. Most of the nation’s inhabitants moved from the balding pate of the island to its fringes, where they were trapped between the wasted land and a rising sea level. Clodumar admonished the western world, characterizing the effect of global warming as cultural genocide and “a rising flood of biblical proportions.” He went on to say, “Small Island States provide not only a moral compass; we are also a barometer of broader visitations wisely heeded by all.”[7]

Journalists from leading western publications have written about the island’s ecological seesaw. A National Geographic article in 1921, “Nauru, the Richest Island in the South Seas,” told of Nauru’s beauty and prosperity; seventy-five years later, a New York Times headline lamenting “A Pacific Island Nation Is Stripped of Everything” emphasized the ecological devastation there in the wake of globalization. The island has also been characterized as a “crystal ball” or microcosm of the earth in heartfelt stories about global ecological distress and tragedy.[8] Funds permitting, Nauru has even developed a plan to vacate the island and buy another atoll, thus becoming an offshore site with its own offshore escape route.

Despite the island’s moral self-image, The Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering frequently cites Nauru—along with Burma, Egypt, Guatemala, Hungary, Indonesia and Nigeria, Bahamas, the Cayman Islands, Liechtenstein, and Panama—for its offshore banking misconduct.[9] Inhabitants of Nauru once sheltered 400 offshore banks— a third of them associated with the Middle East and more than 50 percent with the United States—and the Russian central bank estimated that over US $70 billion moved through Nauru during the 1990s.[10] Australia and New Zealand have used Nauru, The Cook Islands, the Marshall Islands, Vanuatu, Western Samoa, and the Marianas as tax havens.[11]

Australia, while initially unwilling to provide asylum to residents of tiny Pacific islands in the event of their inundation by the rising sea-level, was willing to pay islands including Nauru, Papua, New Guinea, and Fiji millions of dollars to process asylum-seekers from troubled areas around the world.[12] Nauru, in need of money, accepted boatloads of refugees from Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, and Pakistan when Australian Prime Minister John Howard turned them away, claiming lack of space and resources.[13]

Nauru’s bid for cash in exchange for refugee storage has had some of the same effects as the money laundering and offshore banking, the attempt to make money from marginality again landing the country in the center of conflict. The Iraqis and Afghanis seized control of their notoriously grim refugee camp in December of 2002;[14] in the spring of 2004, the Iraqis went on a hunger strike.[15] Nauru’s refusal to permit visas to those visiting the refugees made it a target of Amnesty International.[16] Recently a flotilla of human rights activists attempted to sail to Nauru in protest only to be turned away by Nauruians.[17]

In the interim, the country has been plagued with infrastructure failures, financial difficulties, and inconsistent leadership. In January of 2003, the country lost contact with its Intelsat satellite and thus with the rest of the world. Since the black-out, the presidency has rotated between a few men, mostly previous presidents with health difficulties, changing hands six times in 2003 alone.[18]

Seemingly mythomaniacal dreams of espionage were next. In August of 2003, Nauru brought a case against the US government with whom it had previously had a friendly relationship. The court case was prompted by creditors from the US import export bank Exim wishing to repossess the one airplane that constitutes “Air Nauru.” Nauru claimed that the US government had approached the country after the Bali bombings in 2002 and given it assurances that the plane would not be repossessed if it agreed to provide cooperation in the “Korea program,” close down its offshore banking, and discontinue illegal passport sales. The “Korea program,” according to Nauru, was a plan, under the cooperation of the US and New Zealand, to build a Nauruian embassy in Beijing that would harbor North Korean defectors.[19] Failure to cooperate, Nauru claimed, would have meant sanctions fatal to the country’s economy.

In 2003, Nauru launched a counter-fantasy by implicating two US officials in an anti-terror and defection spy operation. While the US government denies any official contact with Nauru, the court case will prevent the immediate repossession of Nauru’s airplane. The US had consistently opposed Nauru’s banking and passport operations, in part because of links to terror, and as of mid-July 2003, the country was forced to close its offshore bank. But, Nauru claims, the promised US assistance had failed to materialize in return.[20] President Bernard Dowiyogo (elected after the riots and the communication blackout in January of 2003) was sent to the US for medical treatment soon after the election. He allegedly received letters from US Secretary of State Colin Powell attempting to reinforce the proposed deal, but died in March before being able to confirm an agreement.[21] In the meantime, reports in June 2003 of a North Korean scientist who had defected from the North through the island of Nauru proved to be false.[22]

The list of insults and injuries continues. Once a country second only to Saudi Arabia in wealth per capita, Nauru has literally been reduced to begging. It imports its water from Australia. It promised to terminate relations with Taiwan in exchange for millions from the Chinese. The island recently defaulted on a last-ditch loan from General Electric, forcing it to sell off most of its properties, including a hotel in Sydney and Nauru House, its sumptuously furnished quarters in Melbourne’s first skyscraper. Electricity on the island had been available during specified hours in the day, but now Nauru cannot afford to run its power plant or maintain its satellite connections. Nauruians tend to share wealth communally, borrowing each other’s cars or supplies. Yet now, many appear at government offices asking to borrow small sums to buy food.

Former World Bank consultant and Nauru watcher Helen Hughes—who had previously helped to negotiate the terms of their phosphate wealth after the island took control of the industry in the 1970s[23]—releases tough soundbites about her subject to the press. “They have blown close to two billion,” she has said.[24] “Toes are falling off,” another of her comments, was offered to characterize the severity of the interrelated epidemic of obesity, diabetes, and alcoholism that are rampant on the island. Even driving accidents are disproportionately higher in Nauru, a country with very few roads.

In the broader dark comedy of missteps, the island’s strategy of oscillating between righteous innocence and cheating should have been a successful way of simultaneously developing sympathy and resilience. Nauru is a favorite mascot of emotional appeals about the environment, within which it becomes a pitied victim; meanwhile its treatment of refugees makes it a villain among human rights advocates. The combination of corruption and victimhood is the formula of superpowers of the sea who also invariably camouflage their violence and cheating with innocence and invisible ink. Nauru already operated from the premise that one lie is bad, but many lies are productive. Its only true dysfunction, when compared with all of its trading partners and lenders, was that it could not proliferate enough lies, enough forms of cheating and piracy to produce sufficient camouflage. It was an offshore with no offshore of its own. It did not produce its lawlessness and exception on its own behalf; it merely sold that state of exception as a commodity. Nauru made its trading partners yet more innocent as those partners silently shifted disguises, and moved on to more mobile, taut, and locked down territories in the slushy sea.

- Zygmunt Bauman, Wasted Lives: Modernity and its Outcasts (Cambridge: Polity, 2004), p. 80.

- Michael T. Klare, “Oil Wars in the South China Sea,” in Resource Wars: The New Landscape of Global Conflict (New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2001), pp. 109–137; www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/closindx.htm.

- The Economist, 8 September 2000.

- www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/geos/nr.html [link defunct—Eds.]; www.pacific islandtravel.com/nauru [link defunct—Eds.]; The Independent, 3 September 2001.

- The Economist, 8 March 2003.

- Newsday, 27 August 2004, A86. The quote is from Helen Hughes, a Nauru expert.

- Proceedings, Kyoto Conference, 1997.

- Carl N. McDaniel and John M. Gowdy, Paradise for Sale: A Parable of Nature (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), p. 161; Rosamond Dobson Rhone, “Nauru, the Richest Island in the South Seas,”National Geographic, no. 40 (1921), pp. 549–589; and The New York Times, 10 December 1995.

- Since its creation at the G-7 summit in 1989, FATF has served as an intergovernmental body that tracks money laundering around the world. The New York Times, 23 June 2001, A6.

- The Weekend Australian, 4 June 2003.

- www.offshorecorpservices.com/trends.html [link defunct—Eds.].

- Australia eventually offered Nauru an island on its Great Barrier Reef.

- The New York Times, 5 October 2001, A8; The New York Times, 24 November 2001. In one celebrated incident, Richard Branson and a Norwegian ship captain who rescued a shipwrecked group and tried to deliver them to Australia’s Christmas Island both became advocates for the rights of refugees. See The Independent, 3 September 2001.

- The Economist, 8 March 2003.

- BBC Monitoring, 25 May 2004 and 15 June 2004.

- BBC Monitoring, 15 August 2003; AAP Information Services, 30 July 2003.

- BBC Monitoring, 15 May 2004.

- Newsday, 27 August 2004.

- The Weekend Australian, 16 August 2003.

- The Advertiser, 14 July 2003; The Weekend Australian, 14 July 2003.

- The Weekend Australian, 14 July 2003; The Age (Melbourne), 11 March 2003.

- The Korea Herald, 4 June 2003.

- “Island Unto Themselves,” Newsday, 27 August 2004; Quest Economics Database World of Information Country Report, 23 June 2004.

- “Nauru Learning to Live Without Wealth,” The Financial Times, 18 August 2004; “A Sad Tale of Riches to Rags: Nauru in Pacific: GE calls in Receiver,” National Post’s Financial Post & FP Investing, 2 June 2004.

Keller Easterling is an architect, urbanist, and writer. She is the author of Organization Space: Landscapes, Highways and Houses in America, a book that applies intelligence from information technologies to a discussion of American infrastructure and development formats. Her forthcoming book is Enduring Innocence: Global Architecture and its Political Masquerades.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.