Very Funny: An Interview with Simon Critchley

Toward a philosophical history of humor

Brian Dillon and Simon Critchley

In the early 1590s, in one of his short prose fragments entitled Paradoxes, the poet John Donne took apparent exception to a certain traditional view of laughter as a sign of foolishness. The essay conjectures “That a Wise Man is Known by Much Laughing.” Donne writes: “By much laughing thou mayst know there is a foole, not that the laughers are fooles, but that amongst them there is some fool at whome wise men laugh.” The notion of a wise ribaldry is slyly overturned, however, in the second half of Donne’s text. Laughter, it turns out, is merely a function of the “superstitious civility of manners”: we laugh to let it be known to those around us that we recognize folly when we see it. Which is to say, according to a conventional affinity between laughter and abject deformity or even madness, that we become fools in order to prove ourselves wise.

True wisdom, philosophy has often insisted, is a sober state, not given to laughing at others, nor (perhaps especially) at itself. But there also exists a long history of philosophical reflections on humor: from Aristotle’s lost sequel to the Poetics (in which he famously turned from tragedy to address the genre of comedy) to Freud’s reflections on the obscene or tendentious witticism in Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious (1905). Three broad philosophical models for humor can be adduced from this lineage: humor as the expression of a felt superiority, as the release of certain repressed psychological or social energies, and as the sudden, witty spark across the poles of an apparent contradiction or incongruity. In his book On Humor, the philosopher Simon Critchley offers both a history of this tradition and a meditation on the stark and less than consoling truths which humor teaches.

On Humor is in part, he says, the mirror image of his previous book on tragedy, mourning, and death, Very Little, Almost Nothing. But the latter is a curiously light-hearted book, the former actually rather dark: Critchley, in the end, is interested in what he calls, following Samuel Beckett, the “mirthless laugh.” Simon Critchley is Professor of Philosophy in the Graduate Faculty of the New School for Social Research, New York. His other books include The Ethics of Deconstruction and Continental Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction. In 2004, he released a CD with John Simmons entitled Humiliation. His new book, Things Merely Are, was published in March 2005. Brian Dillon spoke to him in London.

Cabinet: How and why does a philosopher become interested in humor?

Simon Critchley: I’ve got a theory of impossible objects; I’m attracted to things that philosophy cannot appropriate or conceptualize. I’ve always been very drawn to the idea of philosophy, as a discourse, confronting things which resist it, and then watching what happens in that play of resistance and attraction. And the three things I’ve focused on in the last few years have been humor, poetry, and music. I’ve got different strategies of impossibility with all three, but one is the humor book: to write a book about humor from a philosophical point of view. Humor in itself as a social practice is what’s interesting. I’m convinced that there are deep philosophical insights yielded through the practice of humor.

Has that opposition between humor and philosophy always been present in philosophy itself?

It’s a very complicated issue, and there are different ways of telling the story. One story would be: the history of philosophy is the history of the repression of laughter, or the attempt to suppress laughter, and that suppression is obviously there in Plato, in the Republic, where the guardians of the polis are not meant to laugh. That continues into religious traditions, particularly monastic traditions, where it was initially proscribed for monks to laugh. So one philosophical strategy is the exclusion of laughter because laughter is animalistic and bestial. Another strategy is to contain it conceptually, to write about it, and there are some remarks in Aristotle: this is what we would have had if we had the second book of the Poetics, on comedy.

At the same time, the philosopher’s seriousness is traditionally an object for ridicule.

Another story would be that nobody takes this story (of the philosophical exclusion of laughter) seriously; nobody in their right minds.... Žižek has a wonderful analysis of totalitarianism: the usual liberal analysis of totalitarianism is that it has to suppress laughter. Laughter is an unruly force, and the great hero of this would be Bakhtin, who in Rabelais and his World talks about the lower bodily stratum and the materiality of laughter; this is a site of popular resistance to totalitarianism. Žižek turns that on its head and says the thing about totalitarianism was that nobody ever took it seriously. It was a joke, and the only people who took it seriously were Western liberals who thought it was serious. You could say very similar things about other, seemingly totalizing discourses, like Christianity, which has been an unruly, comic discourse. Its official discourse might be one thing; but nobody took that seriously, and you can take this all the way back to Plato. Does one take Plato’s exclusion of laughter seriously? It’s really a moot point. In Plato’s dialogues, Socrates is the great ironist, the great comedian in a way, and the levels of irony in the dialogues are infinite. They’re certainly not meant to be read at face value at all; it’s as likely that these things are meant to invite ribaldry and laughter.

Your book is specifically on humor, rather than laughter or the comic. Is it possible to separate these categories with any real rigor? What does the idea of humor offer the philosopher that these others don’t?

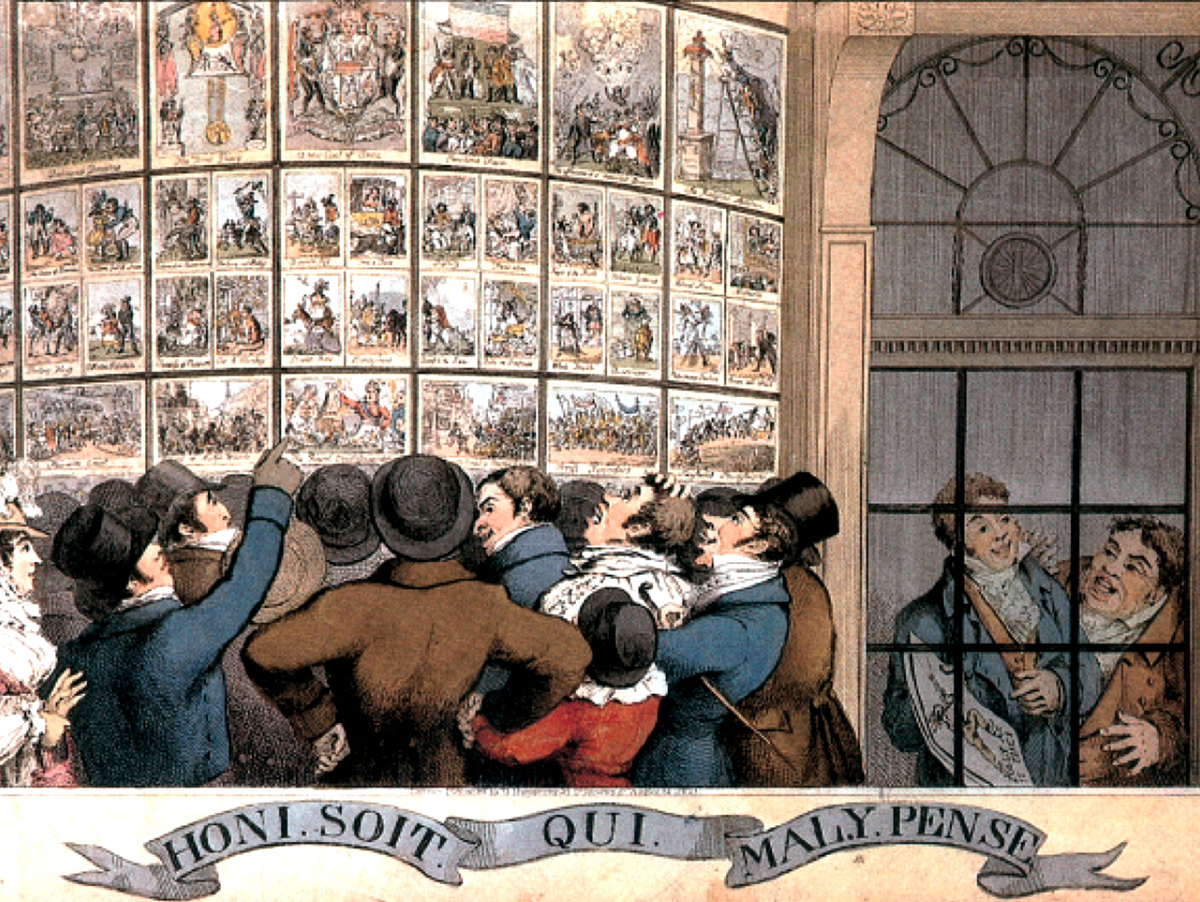

This was initially going to be a book about comedy, but that seemed too broad a focus, and the really peculiar thing, working on non-serious topics, is that there are definitional problems. No one can agree what comedy is, what comedy is not, what the difference is between irony, humor, satire: these are incredibly contested and contestable topics. I chose humor, partly, because I can tell a clear historical story about it: humor begins as a concept in the English language at the end of the seventeenth century, with the shift from the medical theory of the four humors to the modern idea of humor. You can locate it, and its location is one that you can tell a story about in so far as the birth of humor as something jocular (and not as the doctrine of the humors in classical medicine) is tied to the development of what we now think of as liberal democracy. The first theorist of humor is Shaftesbury—in his Characteristics of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times, in 1711—and his idea is that humor is a form of common sense—sensus communis—and that it is something which civilized gentlemen in a democratic, Protestant culture have in common. What civilized gentlemen in a liberal democratic country share is this ability to exercise raillery.

There seems, in that case, to be an analogy between humor and taste, the other category in that period which is also thought of as natural or intrinsic to the individual, but is at the same time, of course, cultivated: a product of society and common sense.

The word that would translate humor in Latin in Cicero is urbanitas; so humor is urbane, it’s urban, it’s a consequence of city life, maybe even of metropolitan life. It’s what civilized people do, share, have in common; so it’s very much like taste. The rise of taste and the rise of humor: you could probably plot similar genealogies for both concepts. Certainly, in Shaftesbury, his whole aesthetic theory is a theory of taste. One place this goes is into Kant: taste for him is something which is artificial, cultivated, but has to be universalizable. There has to be a universal voice, as he puts it, at work in judgments of taste: which is another way of thinking about common sense; the universal voice would be common sense.

Is it possible to say how the shift is effected from humoral theory to a theory of humor? The two meanings seem to compete briefly in the seventeenth century. Why does the modern usage lose that earlier sense of physical, bodily or medical being?

The first recorded usage, according to the OED, which of course you should never believe, is in 1688. There’s obviously a shift—in Elizabethan England, in Shakespeare or Jonson—from a man in his humor, in a certain mood, to something else. We know that shift happens in the seventeenth century, but I’ve got no idea why it happens and why it happens in one particular culture. I hesitate to say “in England.” There is an idea of humor as an essentially English concept; various people make that claim, and the most famous of them is Diderot. In the article on humor in the Encyclopédie, he begins by saying that humor belongs essentially to the English mind: l’esprit Anglais. And then, as an example of English humor, he talks about Swift, who he doesn’t seem to realise is the contrary of Englishness. There’s a tradition of humor, with Shaftesbury in the eighteenth century, which is tasteful, urbane, refined, or Horatian—it’s light, genteel—and against that you have another tradition of humor, embodied in Swift, which is Juvenalian, dark, brooding, cruel, vicious; and in that case it’s Irish. The Anglo-Irish dynamics of humor are very interesting in the way in which this language, English, is internally subverted by traditions of Irish satire. You can trace that, beginning with Swift, and going on to include Beckett, Flann O’Brien, and others.

You would, presumably, need to include Wilde in that tradition; though with Wilde you have a complicated relation to the idea of genteel English humor: his aphoristic dandyism is appropriated from a cultivated English wit, but is also a scurrilous subversion of its conventions. He seems to conflate the two figures that English culture would like to keep separate: the witty fop and the humorous clown. Can one maintain a distinction between wit and humor?

The genealogy of foppery: that would make a good research project. As for wit and humor: I don’t think you can make a hard and fast distinction. One thing I discuss in the book is George Eliot’s article on Heine: a brilliant piece, where she makes a distinction between the English and the Germans. I think one of the interesting things about humor is that the ugly issue of national identity surfaces in a very powerful way, and I think it should. I think we have an easy and complacent internationalism which simply doesn’t acknowledge that we are, all of us, rooted in national traditions which are ugly and horrible and make us what we are. George Eliot divides it up into the English and the Germans, and she’s thinking of wit as Witz, as the putting together of unlikes in a momentary likeness, and that producing a laugh. And that’s indeed true; but then, that would also be true of humor or jokes. In terms of national characteristics, there’s a powerful tradition of Witz in German, which begins with the German Romantics. It’s also the word that Freud uses in his 1905 book on jokes. But, to make matters even worse, the Germanophones are taking the notion of Witz from the concept of esprit, which is what the French are meant to have; just think of Molière. So, according to this fantastic geography, what would distinguish the French and the English would be wit versus humor. My point is that in relation to non-serious concepts you can create all sorts of historical and geographical narratives in order to distinguish them, but basically they are just terribly muddled.

A good deal of critical or philosophical thinking about laughter seems to depend on this very idea of the actual, comic porousness of supposedly hard distinctions. Can you say something about the comedic opposition, for example, between thought and the body?

I think this distinction between thought and the body takes on a decisive form in modernity. Let’s consider Descartes. Descartes looks out of his window in his Meditations and wonders to himself whether what he sees are human beings like himself or automata, robots, dolls, puppets. This is the seed of the problem of skepticism: how can I know that these people are robots or are humans? The philosophical operation of thought that gives birth to the notion of skepticism is a comic operation, and it’s very similar to the operation that you find in Bergson’s definition of comedy. Bergson has two formulations of the same thought: comedy is the encrusting of the mechanical onto the organic, and comedy occurs when we take a person for a thing. Wyndham Lewis very amusingly turns that thought on its head and says what makes us laugh is not when a person becomes a thing but, on the contrary, when a thing becomes a person. A cabbage reading Flaubert: that’s funny. Humor takes place in that gap between the human and the inhuman, between the mechanical and the organic, the living and the dead. It’s a negotiation between those categories: something we do every day.

Although the theory of humor and comedy deals often with the failure of the body or the collapse of logic, it rarely tackles the failure of a joke itself (which is one formal difference from the discourse on taste. Taste is made up of distastes: to express aesthetic revulsion is one way of marking yourself as a connoisseur, but not laughing at a bad joke doesn’t immediately give you a reputation for having a keen sense of humor). Is that moment, of the failed joke, something that can be talked about philosophically?

I have much experience with failure myself: trying to talk about humor, with examples, and just not getting laughs, and that can be simply painful. For example, I gave the same talk on humor to a group of Cambridge graduate students and, three days later, to a group of psychoanalysts. You would have thought the psychoanalysts would understand humor, would have some investment in it. I got big laughs from the Cambridge graduate students and nothing—it was like a morgue—from the psychoanalysts. And I came to the conclusion that it was to do with a sort of intellectual security or assurance those graduate students had. Whether it was real or legitimate or not, they had it and felt comfortable laughing, and the analysts didn’t have that so didn’t feel comfortable laughing. Very odd. Maybe they were analyzing me.

Is there something to be said, then, not only about what we might learn from laughter, but about the place of humor in teaching?

This is a delicate matter because the way in which I work is very simple: if I had the ability, I’d do something else. I’d have been a novelist, or a musician, poet, or a dancer. Because I don’t have that ability, I can be a philosopher and write about those things. In relation to humor, there are people who are genuinely funny, who’ve got funny bones, who I laugh at. I’m not one of them, so I can write about humor, and if people don’t find me funny or don’t find my book amusing, that’s okay. But as a teacher, I suppose I’d like to think that I’m using laughter effectively. Such is vanity. The students might be thinking: he’s a total bloody idiot. And they should; at a certain point I want them to think I’m a total bloody idiot. Students should both admire you and then be repulsed by you. The art of teaching is managing that play of attraction and repulsion; in psychoanalytic terms, of making the transference and breaking it and not letting teaching turn into the crass discipleship one sees too much of in the United States. The interesting thing about the structure of laughter is that you’re opened up in the laugh and that’s when you can be hit. So I try to use humor in teaching to make serious points; it’s only when you’ve opened yourself up through humor that you can be wounded. That’s what it should do, and God knows we need that right now.

There’s a particular sort of tragedy about the teacher, or the philosopher, who tries to make us laugh and fails, as if the gulf between philosophy and the world is suddenly revealed. As a philosopher of humor, you have to court that failure to an even greater degree.

Take a great English comedian like Frankie Howerd: his entire humor was in the fact that he couldn’t tell jokes. But that’s only funny because he’s funny. I think there are people with funny bones: they can tell failed jokes, but it’s because they’re funny. Why are certain people funny? I don’t know. But there are people who are genuinely funny. We want to believe that those people are miserable. The only way we can bear the thought that there are people who are incredibly funny is that they’re miserable; think of the tradition of depressed comedians. But the terrifying thought is that there are people who are genuinely funny and lead quite happy lives, and I think we should resent them for that. As philosophers, the pedagogical task we face is forcing people out of their manic happiness and into normal human misery. We live in cultures of increasing mania and imaginary obsessions, where there’s lots of laughter but it’s deeply humorless.

In your work, Beckett is an important corrective in that regard.

Ah, Beckett. In Beckett’s Watt, you’ve got a distinction between three forms of laughter: the bitter, the hollow, and the mirthless. The bitter laugh laughs at that which is not good, the hollow laugh laughs at that which is not true, but it is the mirthless laugh that is the most interesting, what Beckett calls the “pure laugh,” the risus purus. The mirthless laugh is the highest laugh and it laughs at that which is unhappy. True humor is therapeutic insofar as it allows us to recover from the delusory happiness of ideology into the lucidity of seeing things for what they are. When we see things for what they are—and this is a very philosophical thought and it is the other item that I borrow from Beckett—then we do not laugh, we smile. I end my book on humor with a discussion of smiling, which I see as the final acknowledgment of our humanity. This happens when we look at ourselves from outside ourselves and find ourselves ridiculous. It’s the acknowledgment of one’s ridiculousness in a smile that finally interests me.

Simon Critchley is professor of philosophy at the New School for Social Research, New York and at the University of Essex. He is author of many books, including On Humour (Routledge, 2002), Very Little...Almost Nothing (second edition, Routledge, 2004) and Things Merely Are (Roultedge, 2005).

Brian Dillon is UK editor for Cabinet and writes regularly on art, books, and culture for Frieze, ArtReview, Scotland on Sunday and The Wire. His first book, In the Dark Room, will be published in October 2005. He lives in Canterbury.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.