Breathable Food

Tastes for the new mouth

David Gissen

In the history of architecture and design there have only been a few “effects”—electric light, forced air—that have had the capacity to cause massive environmental and behavioral shifts. Last year at Barcelona’s annual design fair, the Catalonian designer Marti Guixe presented another—breathable food. “Pharma-food, a system of nourishment by breathing,” is an appliance that was developed by Guixe to explore the transformation of food into pure information.

Pharma-food joins the work of other, primarily European, designers who are exploring alternative regimens for such activities as washing or eating. One of Guixe’s Catalonian contemporaries, Ana Mir, is exploring a technology that allows one to wash without water. Like Guixe’s approach, this project would allow washing to occur anywhere. In their work, these designers not only free regimens from their fixed location in relation to certain products; they also free these activities from their traditional engagement with the body. Unlike designers such as Philippe Starck or Richard Sapper, who strive to revise traditional technologies, Guixe has discovered that the problem of eating does not involve the design of a new type of stove, sink, or refrigerator—the problem of eating requires finding a new mouth.

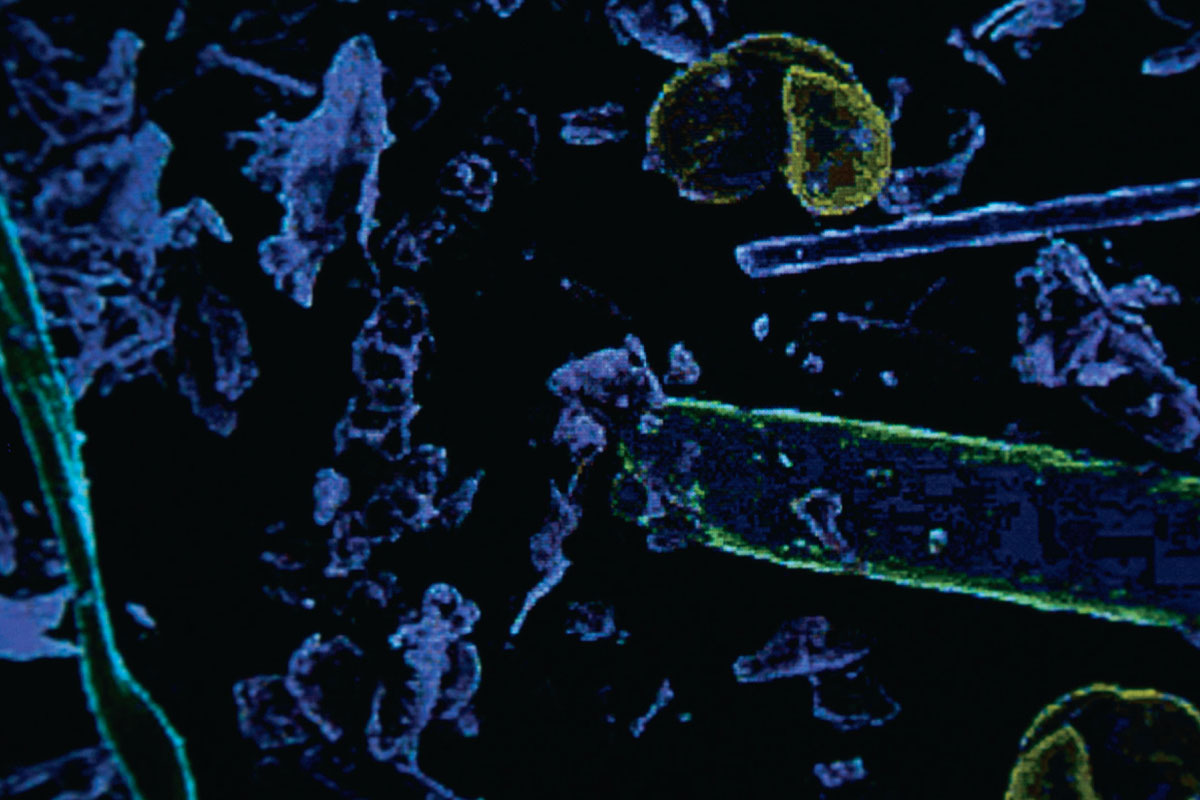

Guixe, who has been studying alternative forms of eating for several years, realized that the breathing of “food” already occurs via the inhalation of dust that hangs in the air at work and at home. Guixe hypothesized that this form of eating, from which one gains a miniscule amount of minerals and vitamins, could be trans-formed into a more potent meal, a “dust-muesli,” that would supply a powerful dose of nutrients. The Pharma-Food appliance, which sprays this ærosolized nutrition, connects to a computer and requires Microsoft Excel to enter exact values for such things as riboflavin, vitamin C, and protein. The combination of these nutrients are saved on the computer as documents with names such as “SPAMT,” which has the nutrient “language” of tomatoes and bread, and “Costa Brova,” a “seafood” dish that is heavy on the iodine and light on carbohydrates. Guixe imagines diners composing these “meals” and sending them as email attachments to other owners of the Pharma-food emitter. “Like MP3,” says Guixe.

While Guixe has explored the experience of eating this information, less explored and of equal significance is where this type of eating can now take place. Guixe imagines Pharma-food in a special “Pharma-bar,” essentially a simple room with tables and chairs and several emitters. But why is this necessary when he has liberated food from kitchens and from forms of ingestion that require utensils and dishes? Pharma-food will allow eating to occur anywhere at any time; on subways, in cars, in our beds, while exercising, sleeping, or making love. Most interesting is what effect this device will have on the home, particularly the American home, which is dominated by the kitchen. While technologies are given free range at work and in other public spheres, the home is typically the place where devices such as Pharma-food are tamed and held in balance by a previous technology that the new device is meant to replace. Central heat did not eliminate the fireplace; it allowed this formerly grimy, soot-filled artifact to become an æsthetic symbol and heart of the American home. People began using fireplaces less, but when they did, they burned wood in them again instead of coal. Similarly, cooking the monthly meal may involve stoking a wood-fueled, cast-iron stove while simultaneously breathing a few appetizers with friends.

David Gissen is associate curator for architecture and design at the National Building Museum in Washington, D.C. He is currently developing an exhibition on human conveyance (elevators, escalators, and moving sidewalks) and one on flying buildings.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.