Fantastic City

Engineering ruins in Cold War America

Joseph Masco

Few societies have invested as thoroughly in ruins as Cold War America. While most civilizations have experienced moments of self-doubt about their future, perhaps even contemplating the ruins that might be left behind as a testament to their existence, it took American ingenuity to transform ruination into a form of nation-building. The invention of the atomic bomb in 1945, with its potential to transform the earth into intergalactic rubble, proved to be utterly transformative for American society. Nuclear fear would soon provide not only the rationale for a new US geopolitical strategy, which ultimately enveloped the Earth in advanced military technology; it also provided officials with a new means of engaging and disciplining American citizens in everyday life. For US policymakers, the Cold War arms race transformed the apocalypse into both a techno-scientific project and a political resource.

Linked to the new global project of Soviet containment was thus the creation of an entirely new kind of social contract in the US, one based not on the protection and improvement of everyday life but rather on the contemplation of ruins. In the 1950s, the mock evacuation of cities under the rubric of “civil defense,” as well as the scientific project of testing America’s industrial and material wealth against the power of the exploding bomb, produced a new commitment to engineering ruins as a form of national theater. Civic leaders and politicians led evacuations of the city for television cameras; the media compared blast damage to fire damage to fallout, and estimated the expected casualty rates had the attack been “real.” It was no longer a perverse exercise to imagine one’s own home and city devastated, on fire and in ruins; it was a formidable public ritual, a core act of official governance, techno-scientific practice, and democratic participation. Indeed, in early Cold War America it became a civic obligation to collectively imagine, and at times theatrically enact, the physical destruction of the nation-state.

Cold War ruins are, consequently, not the end of the story, but rather always offer a new beginning, becoming the markers of a new kind of social intimacy grounded in highly detailed renderings of theatrically rehearsed mass violence. The intent of these public spectacles was not defense in the classic sense of avoiding violence or destruction but rather a psychological reprogramming of the American public for life in a nuclear age. After the Soviets became the world’s second nuclear power in 1949, US policy makers were concerned that nuclear terror would become so profound that the American public would be unwilling to support the military and geopolitical agenda of the expanding Cold War. The immediate challenge, as US nuclear strategists saw it, was to avoid an apathetic public (which might just give up) on the one hand or a terrorized public (unable to function cognitively) on the other. For the Eisenhower administration, the solution was a new kind of social engineering project, pursued with help from the advertising industry, to teach citizens a specific kind of nuclear fear.

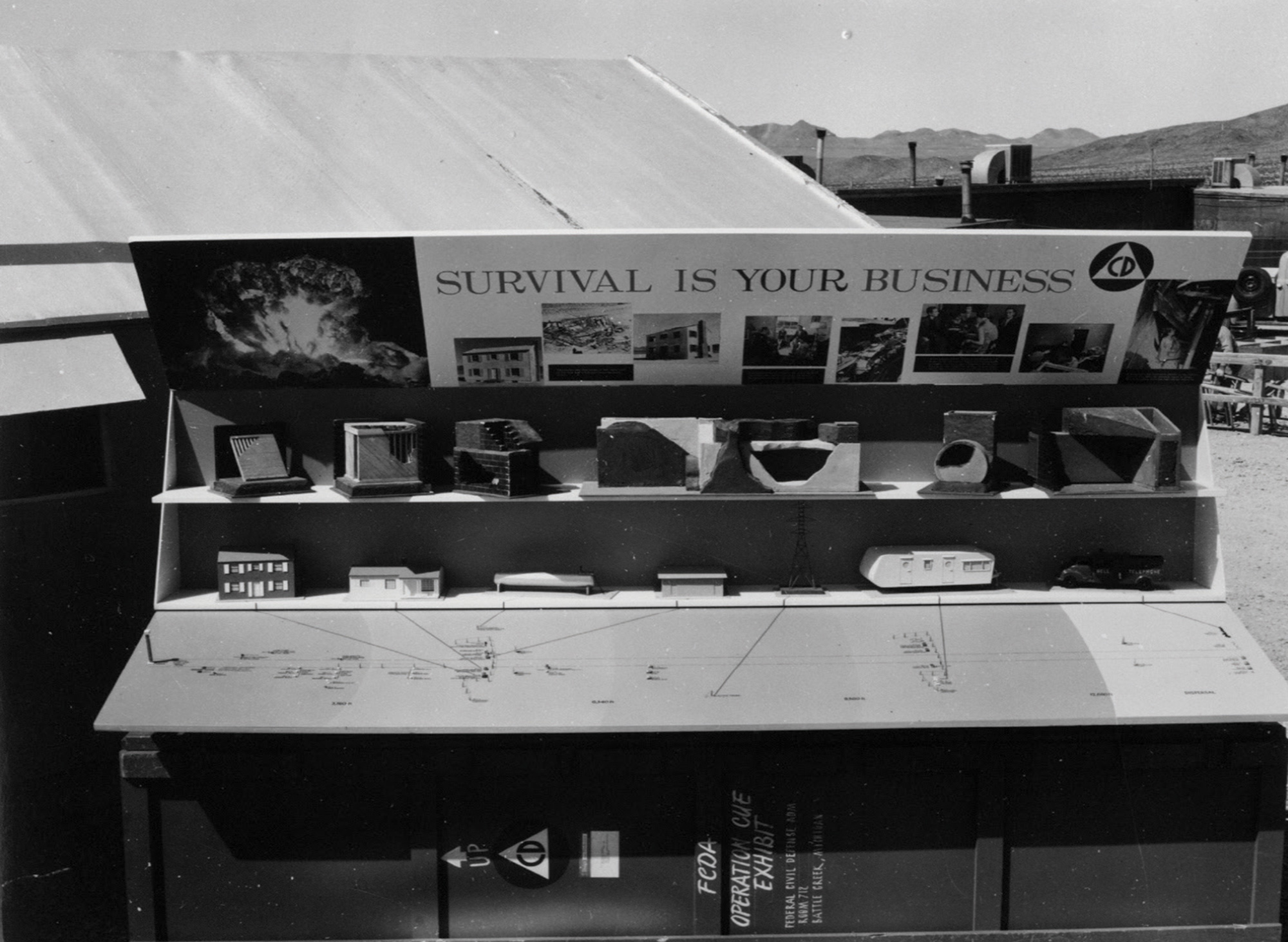

As Guy Oakes argues in The Imaginary War, the Civil Defense programs of the 1950s and 60s were designed to “emotionally manage” US citizens. The formal goal of this state program, he notes, was to transform “nuclear terror,” which was interpreted by officials as a paralyzing emotion, into “nuclear fear,” an affective state that would theoretically allow citizens to function in a time of crisis. In addition to turning the domestic space of the home into the front line of the Cold War, Civil Defense argued that citizens should be prepared every second of the day to deal with a potential nuclear attack. In doing so, the Civil Defense program shifted responsibility for nuclear war from the state to its citizens by making public panic the enemy, not nuclear war itself. The Civil Defense slogan—“Survival is your business”—sums up the new colonization of everyday life with nuclear logics and fear.

But as one key policy manual from the RAND Corporation cautioned, this “psychological inoculation” needed to be finely calibrated: the destruction had to be real enough to mobilize the public but not so real as to invalidate the concept of defense altogether (a distinct challenge in an age of increasingly powerful thermonuclear weapons which offered no hope of survival to urban residents). The federal response was an elaborate propaganda campaign aimed at producing a new generation of Americans psychologically prepared to fight a long cold war, or a very short nuclear one.

Here is how a US Civil Defense film from 1956 entitled, Let’s Face It, described the problem posed by nuclear warfare:

The tremendous effects of heat and blast on modern structures raise important questions concerning their durability and safety. Likewise, the amount of damage done to our industrial potential will have a serious effect upon our ability to recover from an atomic attack. Transportation facilities are vital to a modern city. The nation’s lifeblood could be cut if its traffic arteries were severed. These questions are of great interest not only to citizens in metropolitan centers but also to those in rural areas who may be in a danger zone because of radioactive fallout from today’s larger weapons. We could get many of the answers to these questions by constructing a complete city at our Nevada Proving Ground and then exploding a nuclear bomb over it. We could study the effects of damage over a wide area, under all conditions, and plan civil defense measures accordingly. But such a giantic undertaking is not feasible.

In this form of Cold War thinking, one must destroy the city to understand how to protect it: ruins, in other words, hold the key to national survival. The narrator then reveals that they have built, not a metropolis, but rather “representative units of a test city” for just that purpose:

With steel and stone and brick and mortar, with precision and skill—as though it were to last a thousand years. But it is a weird, fantastic city. A creation right out of science fiction. A city like no other on the face of the earth. Homes, neat and clean and completely furnished, that will never be occupied. Bridges, massive girders of steel spanning the empty desert. Railway tracks that lead to nowhere, for this is the end of the line. But every element in these tests is carefully planned as to its design and location in the area. A variety of materials and building techniques are often represented in a single structure. Every brick, beam, and board will have its story to tell. When pieced together these will give some of the answers, and some of the information we need to survive in the nuclear age.

A weird, fantastic city, indeed. The Nevada Test Site was the location not of simulated nuclear war but of the real thing—as the Atomic Energy Commission built homes, industrial plants, roads, bridges, railroads, forests, and farms to test against the bomb.

The images presented here are from 1955’s Operation Cue—the largest Civil Defense spectacle of its time. The mannequins that populated the test site’s houses and cars are stand-ins for the American public, who watched the destruction live on television. The state-of-the-art consumer items donated from American industry (cars, furniture, clothing, appliances, radios, and televisions) turned this weird city into a capitalist dream space; an idealized American suburb, fresh off the assembly line.

The mannequin families that were intact after the explosion were soon on a national tour, complete with tattered and scorched clothing. J.C. Penney’s Department store, which provided the garments, displayed these post-nuclear families in its stores around the country with a sign declaring, “This could be you!” Inverting a standard advertising appeal, it was not the blue suit or polka dot dress that was to be the focal point of viewer’s identification. It was the mannequin as survivor, whose very existence seemed to illustrate that you could indeed “beat the a-bomb,” as one Civil Defense film of the era promised. Invited to contemplate their life among the ruins or as mannequins, the national audience for Operation Cue was caught in a sea of mixed messages about the power of the state to control the bomb. These melodramas of the nuclear age did not resolve the problem of the bomb, but rather, focused citizens on emotional self-discipline. It asked them to live on the knife’s edge of psychotic contradiction, with the stakes being nothing less than survival itself.

One afterimage of Cold War emotional management campaigns is found in our continued pleasure in and commitment to making ruins and then searching the wreckage like tea leaves for signs about our future. While we no longer detonate atomic bombs on fabricated cities populated with mannequins, we do have yearly spectacles in which America’s cities are reduced to smoldering ruins all in the name of fun. The Hollywood blockbuster today—with its fearsome life-ending asteroids, aliens, earthquakes, floods, and wars—allows us to rehearse our own destruction much as our parents and grandparents did in the 1950s. These techno-aesthetic displays of finely rendered destruction are a unique form of American expressive culture, the product of a Cold War nuclear logic that continues to haunt America—to inform how it experiences acts of mass violence and how it then engages the world. When contemplating these black-and-white images from 1955, imagine if it were otherwise, imagine if we had no such use for ruins.

The source of the photographs accompanying this article was given incorrectly as the film Let’s Face It in the print edition of this issue.

Joseph Masco teaches anthropology at the University of Chicago, where he writes about technology, politics, aesthetics, and US national security culture.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.