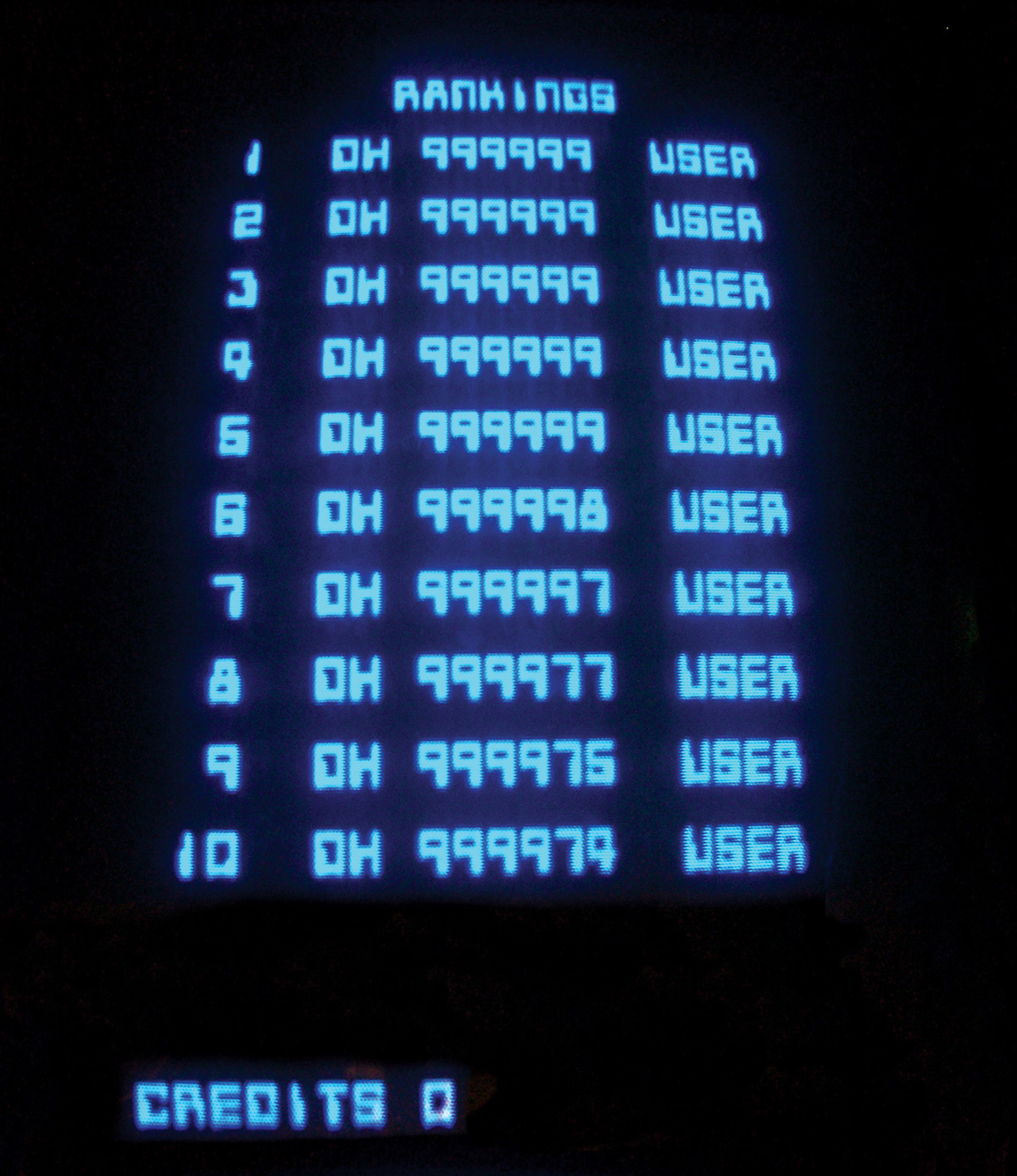

09.

All that counts here is the score. As for who owns

the teams and who runs the league, best not to ask. As for who is

excluded from the big leagues and high scores, best not to ask. As for

who keeps the score and who makes the rules, best not to ask. As for

what ruling body does the handicapping and on what basis, best not to

ask. All is for the best in the best—and only—possible world. There

is—to give it a name—a military entertainment complex, and it

rules. Its triumphs affirm the rule of the game and the rules of the game.

10.

Everything

the military entertainment complex touches turns to digits. Everything

is digital and yet the digital is as nothing. It just beeps and blinks

and reports itself in glowing alphanumerics, spouting stock quotes on

your cell phone. Sure, there may be vivid 3-D graphics. There may be

pie charts and bar graphs. There may be swirls and whorls of brightly

colored polygons blazing from screen to screen. But these are just

decoration. The jitter of your thumb on the button or the flicker of

your wrist on the mouse connect directly to an invisible, intangible

gamespace of pure contest, pure

agon. It doesn’t matter if your

cave comes equipped with a Playstation or Bloomberg terminal. It is all

just an algorithm with enough unknowns to make a game of it.

11.

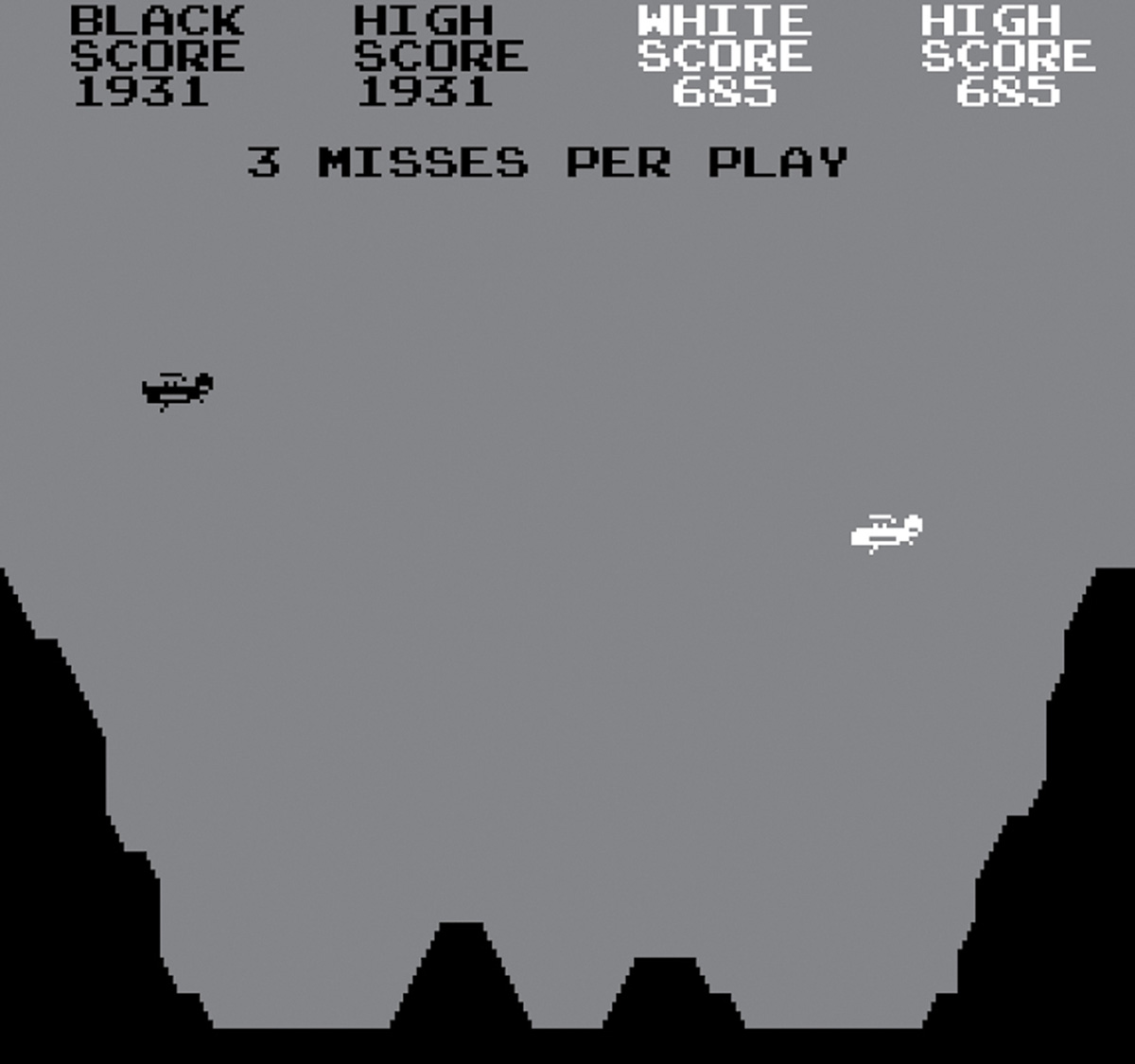

Once

games required an actual place to play them, whether on the chessboard

or the football field. Even wars had battlefields. Now global

positioning satellites grid the whole earth and put all of space and

time in play. Warfare, they say, now looks like video games. Well,

don’t kid yourself. War is a video game—for the military entertainment

complex. To them, it doesn’t matter what happens “on the ground.” The

ground—the old-fashioned battlefield itself—is just a necessary

externality to the game. Zizek: “It is thus not the fantasy of a purely

aseptic war run as a video game behind computer screens that protects

us from the reality of the face-to-face killing of another person; on

the contrary it is this fantasy of face-to-face encounter with an enemy

killed bloodily that we construct in order to escape the Real of the

depersonalized war turned into an anonymous technological

operation.”[3]

12.

The old class antagonisms have not gone away, but are hidden beneath levels of rank, where each measures their worth against others in the size and price of their house, the size and price of their vehicle, and where, perversely, working longer and longer hours is a sign of winning the game. Work becomes play. Work demands not just one’s mind and body but also one’s soul. You have to be a

team player. Your work has to be creative, inventive, playful—ludic, but not ludicrous.

13.

No

games are freely chosen any more. Not least for children, who if they

are to be the successful offspring of successful parents, find

themselves drafted into endless evening shifts of team sport. The

purpose of which is to build character, of course. Which character? The

character of the

good sport. Character for what? For the

workplace, with its team camaraderie and peer-enforced discipline. For

others, work is still just dull, repetitive work, but the dream is to

escape into the commerce of play—to make it into the major leagues, or

compete for record deals as a

diva or a

playa in the

rap game.

And for still others, there is only the game of survival. Biggie: “If I

wasn’t in the rap game / I’d probably have a key knee-deep in the

crack

game.”[4] Play becomes everything to which it was once opposed. It is work, it is serious, it is morality, it is necessity.

14.

The

old identities peter out. Nobody has the time. The gamer is not

interested in playing the citizen. The gamer elects to choose sides

only for the purpose of the game. This week it might be as the Germans

vs. the Americans. Next week it might be as a gangster against the law.

If the gamer chooses to be a soldier and play with real weapons, it is

as an

Army of One, testing and refining personal skill points.

The shrill and constant patriotic noise you hear through the speakers

masks the slow erosion of any coherent fellow feeling within the

remnants of a national space. This gamespace escapes all borders. All

that is left of the nation is an everywhere that is nowhere, an atopia

of noisy, righteous victories and quiet, sinister failures. Manifest

destiny—the right to rule through virtue—gives way to its latent

destiny—the virtue of right through rule.

15.

The

gamer is not really interested in faith, although a heightened rhetoric

of faith may fill the void carved out in the soul by the insinuations

of gamespace. The gamer’s God is a game designer. He implants in

everything a hidden algorithm. Faith is a matter of the ability to

intuit the parameters of this intelligent design and score accordingly.

All that is righteous wins; all that wins is righteous. To be a

loser or a

lamer

is the mark of damnation. Gamers confront each other in games of skill

that reveal who has been chosen by the game as the one who has most

fully internalized its algorithm. For those who despair of their

abilities, there are games of chance, where grace reveals itself in the

roll of the dice. Caillois: “Chance is courted because hard work and

personal qualifications are powerless to bring such success

about.”[5] The gambler may know what the gamer’s faith refuses to countenance.

16.

To be a gamer is to live by nothing but

level,

which has meaning only in relation to the levels ranked above or below.

Identity loses its qualitative dimension. Gamespace leaves its mark on

the gamer in the reduction of self to score. Questions of ethnicity,

sexuality, gender, or race, nation, tribe, or even species become

purely arbitrary. Play as whoever or whatever you like. Choose your

skin. Gamers don’t care. It’s all an agon of competing abilities, and

abilities all have their measure. It all ends in a summary decision:

That’s Hot! One hopes, or if not,

You’re Fired! Got questions about qualities of Being?

Whatever.

17.

So

this is the world as it appears to the gamer: a matrix of endlessly

varying games, all reducible to the same principles, all producing the

same kind of subject who belongs to this gamespace in the same way—as a

gamer to a game. What would it mean to lift one’s eye from the target,

to pause on the trigger, to unclench one’s ever-clicking finger? Is it

even possible to think outside The Cave™? Perhaps with the triumph of

gamespace, what the gamer as theorist needs is to reconstruct the

deleted files on those who opposed gamespace with their revolutionary

playdates. Debord, for example, who declared: “I have scarcely begun to

make you understand that I don’t intend to play the

game.”[6] Now there was a player unconcerned with an

exit strategy.