Five O’Clock Shadows

Losing by a razor-thin margin

Colby Chamberlain

“Don’t Let ‘5 O’clock Shadow’ Start a Whispering Campaign,” warns a 1937 print advertisement for Gem Razors and Blades. “Let down a little in your personal appearance and it’s just human nature for others to surmise that things aren’t so good with you!”[1] In the accompanying image, two women point and look askance at someone unseen but presumably hapless—and indubitably ill-shaven. Defining five o’clock shadow as “that unsightly beard growth which appears prematurely at about 5 P.M.,’” Gem Blades used the variation “Avoid 5 O’clock Shadow” as its company slogan well into the 1940s.[2] It was an advertising campaign aimed squarely at social anxiety, invoking the shadow to conjure up everything ominous and unwelcome about a day’s worth of facial hair. Today, in an age distant enough from the last episode of the 1980s television series Miami Vice to have absorbed in full the impact of Don Johnson’s designer stubble, five o’clock shadow has lost any such sinister implications. At one time, however, it was the very specter of personal and professional calamity—so much so that one case of five o’clock shadow left an indelible mark on the face of US politics.

The 1960 presidential contest between Vice President Richard Nixon and Senator John Kennedy was the first to feature a series of televised debates. “Never before have so many people seen the major candidates for President of the United States at the same time,” NBC newsman Frank McGee put it when he introduced the second debate on October 7, “and never until this series have Americans seen the candidates in face-to-face exchange.”[3] The debates were a nod to the growing importance of television, which by then already reached nine out of ten households in the United States. Nixon had previously enjoyed some success with the medium, such as when he rescued his 1952 Vice Presidential candidacy from allegations of corruption with his “Checkers” speech. Television cameras, however, hardly flattered his appearance—particularly given his naturally pale skin and heavy beard. Just two weeks prior to the first debate, he discussed his predicament with television anchor Walter Cronkite: “I get letters from women, for example, sometimes—and men—who support me, and they say, ‘Why do you wear that heavy beard when you are on television?’ Actually, I don’t try, but I can shave within thirty seconds before I go on television and still have a beard, unless we put some powder on, as we have done today.”[4] The dark shadow also dogged Nixon in print thanks to his frequent appearances in the work of Washington Post cartoonist “Herblock” (Herbert Block), whose caricature of the politician had badly needed a shave since 1948.[5]

The first of the debates took place at a CBS studio in Chicago on 26 September. Nixon typically depended on a special blend of powders for television appearances, but when Kennedy declined makeup, an intimidated Nixon did likewise—evidently giving greater weight to the insinuations that using cosmetics might invite than the importance of his appearance onscreen. It was a gross miscalculation. Kennedy had recently been campaigning in California, and a fresh tan burnished his already photogenic features. Nixon, on the other hand, was recovering from a serious knee infection that had left him twenty pounds lighter than usual. Nevertheless, with an audience of 70 million about to tune in, Nixon refused the network’s cosmetics and instead sent an aide to a nearby drugstore to pick up a package of Lazy Shave.[6]

Lazy Shave “Hides the Beard!” claimed the box copy. A “color-cake for between shaves,” it was essentially a powder makeup thick enough to mask a five o’clock shadow for a few extra hours.[7] Its creator, Max Factor, packaged the powder as part of its Hollywood Signature line of “grooming essentials” for men. Just as the Gillette Company had done since 1946 through its sponsorship of The Gillette Cavalcade of Sports, Max Factor took out advertisements featuring ballplayer spokesmen in newspaper sports pages to help obscure their products’ essentially cosmetic function, which might begin to explain why Lazy Shave so regretfully eluded Nixon’s definition of makeup.[8] Oddly enough, the Max Factor brand first came to prominence as a fixture of Hollywood, where its eponymous founder developed cosmetics exclusively for actors and actresses appearing before the camera.[9] Lazy Shave, needless to say, was a later invention. During the debate, Nixon began to sweat under the studio lights, and the makeup melted off his cheeks.

The rest, as they say, is history. Nixon’s pale complexion and dark jowls unnerved audiences, and Kennedy won the crucial first debate on the strength of his good looks and composure. His success that evening carried him into the White House by a razor-thin margin. It was not, however, total victory. Those who listened to the debate on the radio (among them Kennedy’s running mate, Lyndon Johnson) awarded the win to Nixon. A debate champion since his high school years, Nixon had kept his discussion of the issues focused even as his appearance unraveled. “Nixon ... suffered a handicap that was serious only on television,” observed Daniel Boorstin in his prescient 1962 book The Image: or, What Happened to the American Dream. Boorstin used the term “pseudo-event” to describe the increasing dramatization of society and politics through their transformation into a series of televised spectacles. “If we test Presidential candidates by their talents on TV quiz performances,” he argued, “we will, of course, choose presidents for precisely these qualifications. In a democracy, reality tends to conform to the pseudo-event. Nature imitates art.”[10] To Boorstin, Nixon was the first major victim of the pseudo-event’s up-ending of politics, a presidential candidate judged on the basis of his audition as a television personality. As the writer Hunter S. Thompson put it, “The mushrooming TV audience saw [Nixon] as a truthless used-car salesman, and they voted accordingly.”[11]

That label of salesman dogged Nixon through his career, alternately as praise for his abilities or doubt of his good intentions. The quip “Would you buy a used car from this man?”, usually attributed to the humorist Mort Sahl, was in equal measures comedic and genuinely concerned.[12] In effect, Nixon provoked the same ambivalence as professional salesmen themselves, who, as a class, traded on an aura of trustworthiness and for whom a clean shave was an essential outward manifestation of their integrity. Henry Babbitt, the real estate salesman in Sinclair Lewis’s satire of the 1920s, begins the day struggling with his razor: “Furiously he snatched up his tube of shaving-cream, furiously he lathered with a belligerent slapping of the unctuous brush, furiously he raked his plump cheeks with a safety-razor. It pulled. The blade was dull. He said ‘Damn—oh—oh—damn it!’”[13] Willy Loman, Babbitt’s cultural successor, lives in a house that “smells of shaving lotion.”[14]

What Nixon shared with the average salesman— fictional or otherwise—was membership in the expanding ranks of the middle class. Just as the phrase five o’clock shadow made pointed reference to the 9-to-5 schedule of the typical worker, the contest between Nixon and Kennedy was as much a drama of origins as it was of political positions. The son of a California lemon farmer, Nixon had made his way through government by virtue of a fierce—and fiercely adversarial—Quaker work ethic. “I won my share of scholarships, and of speaking and debating prizes in school,” Nixon wrote of his time at Whittier College “not because I was smarter but because I worked longer and harder than some of my gifted colleagues.”[15] The same competitive spirit that won Nixon accolades, however, also gained him a reputation for expendable principles and calculated ruthlessness. His ambitions were as plainly evident as his beard. Kennedy’s, by contrast, came packaged in an air of privilege and public service. Aristocratic in upbringing and demeanor, Kennedy expressed his dislike of Nixon by claiming he lacked taste.[16]

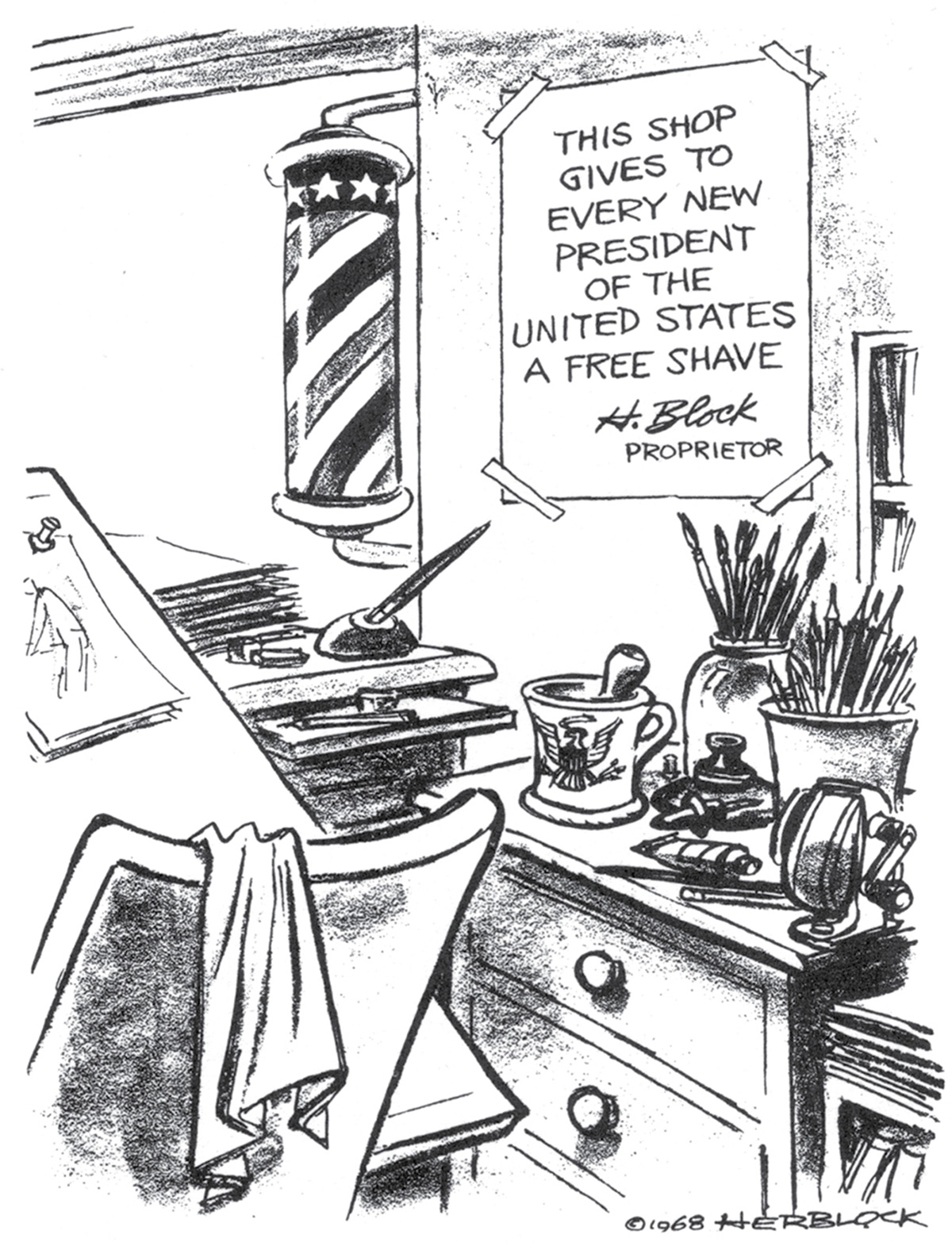

The lessons of that first debate—Lazy Shave and all—were quickly learned, and the significance of television to political practice has seldom since been underestimated. After losing the presidency in 1960 and the governorship of California in 1962, Nixon joined a law firm in New York City and bought property in Florida and California, in part to maintain the sort of tan that Kennedy had sported that fateful night. Meanwhile, a perusal of the October 1960 issue of Gentleman’s Quarterly reveals a single beard among the clean-cut profiles in tweed and houndstooth, a harbinger of an emerging counter-culture that, among other accomplishments, transformed facial hair’s relationship to class, politics, respectability, and cool. All of this did little, however, to rehabilitate Nixon’s shadow, whose superficial suggestion of deviousness and double dealing lingered on (and eventually proved, ironically enough, wholly accurate and entirely warranted). In fact, on the day Nixon won the presidency in 1968, the shrewdest observer of Nixon’s perpetual stubble, Herblock, made a congratulatory if back-handed gesture toward the president-elect. His comic that morning depicted the cartoonist’s own studio, with a few choice additions: a barber’s pole, a shaving brush mug emblazoned with the presidential seal, and a sign on the wall reading: “This shop gives to every new president of the United States a free shave.”

- Advertisement for Gem Razor and Blades, Time, 11 October 1937, p. 33. According to the OED, this advertisement is the first recorded usage of this term.

- “Advertising News and Notes,” The New York Times, 13 February 1943, p. 20.

- Footage of the debate available at www.veoh.com/videoDetails.html?v=e87521tQJWkN7S [link defunct—Eds.].

- Christopher Matthews, Kennedy and Nixon (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), p. 144.

- Stephen J. Whitfield, “Nixon as a Comic Figure,” American Quarterly, vol. 37, no. 1 (Spring 1985), p. 116.

- Theodore H. White, The Making of the President, 1960 (New York: Atheneum, 1961), p. 293.

- Advertisement for May Company, The Los Angeles Times, 15 June 1951, p. 20.

- Advertisement for Max Factor Hollywood Signature, The New York Times, 4 March 1953, p. 34.

- “Cosmetics Bid for Fame,” The Los Angeles Times, 26 April 1925, p. B6.

- Daniel Boorstin, The Image: or, What Happened to the American Dream (New York: Atheneum, 1962). Citation from later edition, re-titled The Image: A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America (New York: Vintage Books, 1992), p. 43.

- Hunter S. Thompson, Better than Sex: Confessions of a Political Junkie (New York: Random House, 1994), p. 243.

- Whitfield, op. cit., p. 116.

- Sinclair Lewis, Babbitt (New York: Penguin Group, Signet Classics, 1998), p. 5.

- Arthur Miller, Death of a Salesman (New York: Penguin Group, Penguin Twentieth-Century Classics Edition, 1998), p. 3.

- Tom Wicker, One of Us: Richard Nixon and the American Dream (New York: Random House, 1995), p. 9.

- Arthur M. Schlesinger, A Thousand Days (Boston: Mariner Books, 2002), p. 65.

Colby Chamberlain is managing editor of Cabinet.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.