Square Watermelons and Leg Art

Exploring the Associated Press Photo Library

Jocko Weyland

(For D.B.)

When I started working at the Associated Press in 1991, the organization—founded in 1848 when six New York City papers agreed to pool efforts in collecting international news—bore little resemblance to the one that began with a single office in Halifax, Nova Scotia, located there to telegraph to New York incoming news brought by ship from Europe. In 1900, the modern AP was incorporated as a not-for-profit cooperative. Mailed photo service began in 1927; this was followed eight years later by wire photos, thus enabling papers to publish pictures the same day they were taken. In 1938, the AP moved into its own building at Rockefeller Center decorated with Isamu Noguchi’s News sculpture above its entrance, and concurrently the photo library was established to store negatives coming to headquarters from around the world. News photos were first transmitted by satellite in 1967 and by 1982 transmission by phone line was replaced by a satellite color photo network called Laser Photo II. Since 1996, all AP photos have been transmitted digitally, and today the AP’s website posts upwards of 1,000 photographs a day.

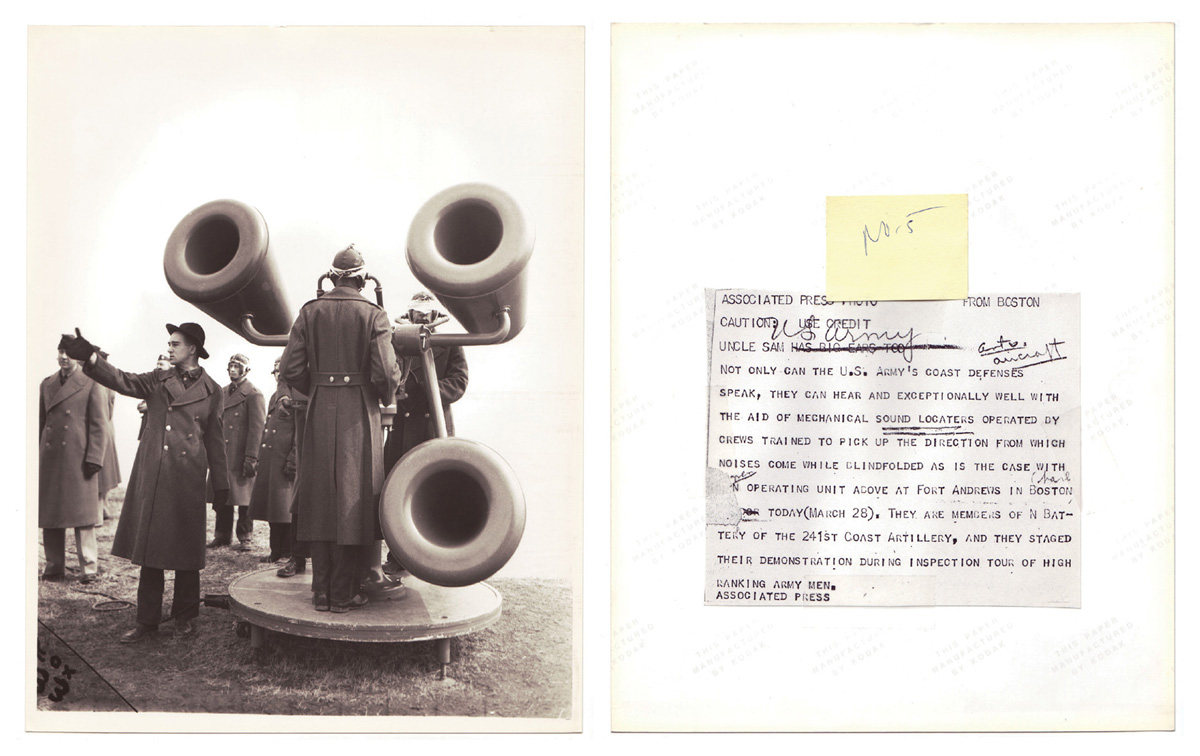

The Associated Press Photo Library serves thousands of newspaper, television network, and magazine members whose editors call the library to ask for a photo that is not currently available on the AP website. Today, virtually all material, including a small fraction of the library’s “historical” images, is available digitally. Negatives are no longer admitted to the library, though requests are still made for older negatives that have not yet been digitized. The photographs shown here come from the bygone era when negatives still flooded into the sixth floor of 50 Rockefeller Center, before the AP left for its current home on Manhattan’s far west side in 2002. When I first started working as a photo researcher at 50 Rock, the Library was a room about 200 feet long by 60 feet wide crammed full of forty-year-old steel file cabinets, temporary cardboard files, miscellaneous boxes, manual and electric typewriters, photocopiers, phones, many and sundry inscrutable scraps of paper covered in scribbled requests, and roughly thirty million negatives and prints. The floor literally sagged from the weight of the file cabinets that stood a little under six feet high, with approximately ten rows stretching to the back of the room, each row about twenty-five feet long emanating from a central aisle. On one side were “Personality” files and on the other were “Subjects.” In the back were boxes of discarded film, the “Old Color” files (separated from the rest before papers were printed in color), and an anteroom overflowing with millions of images from World War II and other twentieth-century conflicts.

During that diluvian age before email, the phones would ring, sometimes off the hook like a clichéd scene of a busy newsroom in the movies, and a librarian would answer. An AP editor on a different floor or someone calling from the Honolulu Advertiser or the Des Moines Register (or Newsweek or 60 Minutes) would ask for a photograph to be transmitted or a print mailed to them. It could be any photo in the library, and the requests ran the gamut from the comically ludicrous and/or vague (“Do you have any actual negatives from the Revolutionary War?” or “A nice scene setter, like maybe someone in a canoe on a lake in the spring”) to the exactingly precise. In the latter case, the editor had a subject or a name, a date, a trans-reference number (such as LA102 of 10/21/1988, which denoted the second color photo sent out by the Los Angeles Bureau on that particular date), and maybe a photographer’s name. My job as a librarian was to find those photos, often in little or no time. (“When’s your deadline?” “Yesterday!”) Considering the multiple possibilities of human error, unreliability, misinformation, theft, loss, misplacement, or the negative being in someone else’s possession at that instant, it borders on the miraculous that eight times out of ten the pictures were found.

Since the AP is an organization devoted to the news, the majority of pictures were news photos—photojournalism depicting wars, crime, elections, mudslides, football games, and award ceremonies. That is, the News. When I started, I was mostly retrieving either mundane news-of-the-day photos or what could be considered the “hits”—the Iwo Jima flag raising, the girl running from the napalm strike in Vietnam, Ronald Reagan being shoved into the limousine after John Hinckley’s assassination attempt, Michael Jordan flying through the air to dunk. These “Free Birds” of news photography were pictures with an undeniable news component, broad appeal, and a literal relation to generally agreed-upon history.

After a few months of working within this rather narrow spectrum, however, I discovered an entirely different layer of imagery that didn’t have much to do with the news and nobody ever requested. The members didn’t know these gems existed, and even if they did, they wouldn’t have wanted them. It started with a co-worker saying, “Check this out,” and showing me something that made us laugh or go, “Whoa!” Pictures resplendent with a wide range of “human interest”—all beguilingly esoteric, and all completely not newsworthy. Spurred on by these examples, I started looking for more oddities and unwanted cast-offs, and that’s when the Library really got interesting. Delving deeper into the dusty cardboard Oxford files with their faded pink labels, my first eureka moment occurred when I came upon a picture of a woman holding two square watermelons. The photo was odd, intriguing, a little unsettling, and also funny. I don’t remember how or why I stumbled onto the “Fruits: Watermelons” file, but when I found that picture, the Library took on a whole new meaning and was transformed into an unfathomably deep well of eccentric people and outmoded ideas. I was hooked, and ended up spending much of the next five years mining those chemically odiferous files for pictures that, for pure visual thrill, might match the excitement I felt when I first saw those square watermelons.

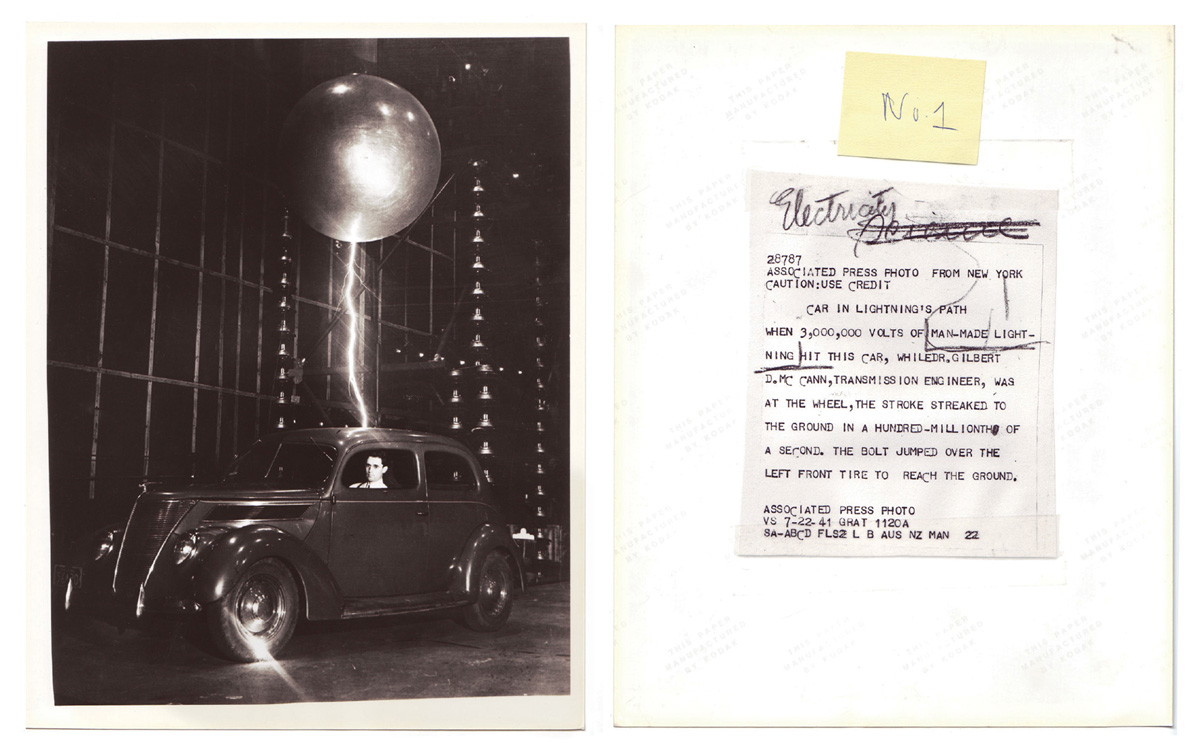

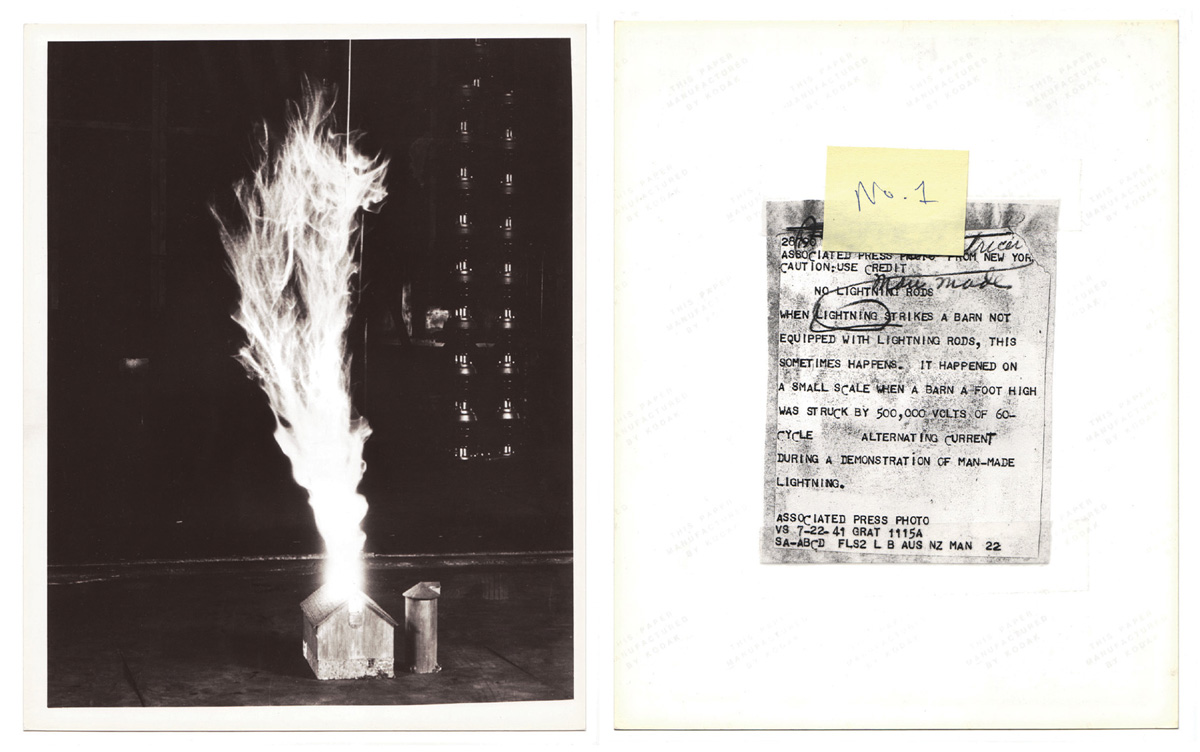

Ostensibly, the Library was about news and history—Stalin, Roosevelt, and Churchill at Yalta, that kind of thing. Parallel to that official “image-world,” there existed an alternative picture made up of untold numbers of singular photographs representing a less-examined outside world, all resting peacefully inside yellowing manila envelopes in the form of black-and-white negatives, mostly glorious 4 x 5s. After 10 pm, when the phone rang less frequently, the real exploring commenced. I dove headlong into every envelope of interest, which was then sent down to the darkroom to come back the next day via dumbwaiter from two floors below as a non-archival 8 x 10 inch print. The guys in the darkroom jokingly called this “G-work” and it was understood that it didn’t pertain to regular AP business. As I started amassing these images, a photographic map emerged of what had been momentarily seized upon and then dropped from public consciousness and the generally accepted version of history. Almost every weird, foolhardy, visionary, misguided, quietly heroic, or insane manifestation of human nature was commemorated by a photograph somewhere in that room.

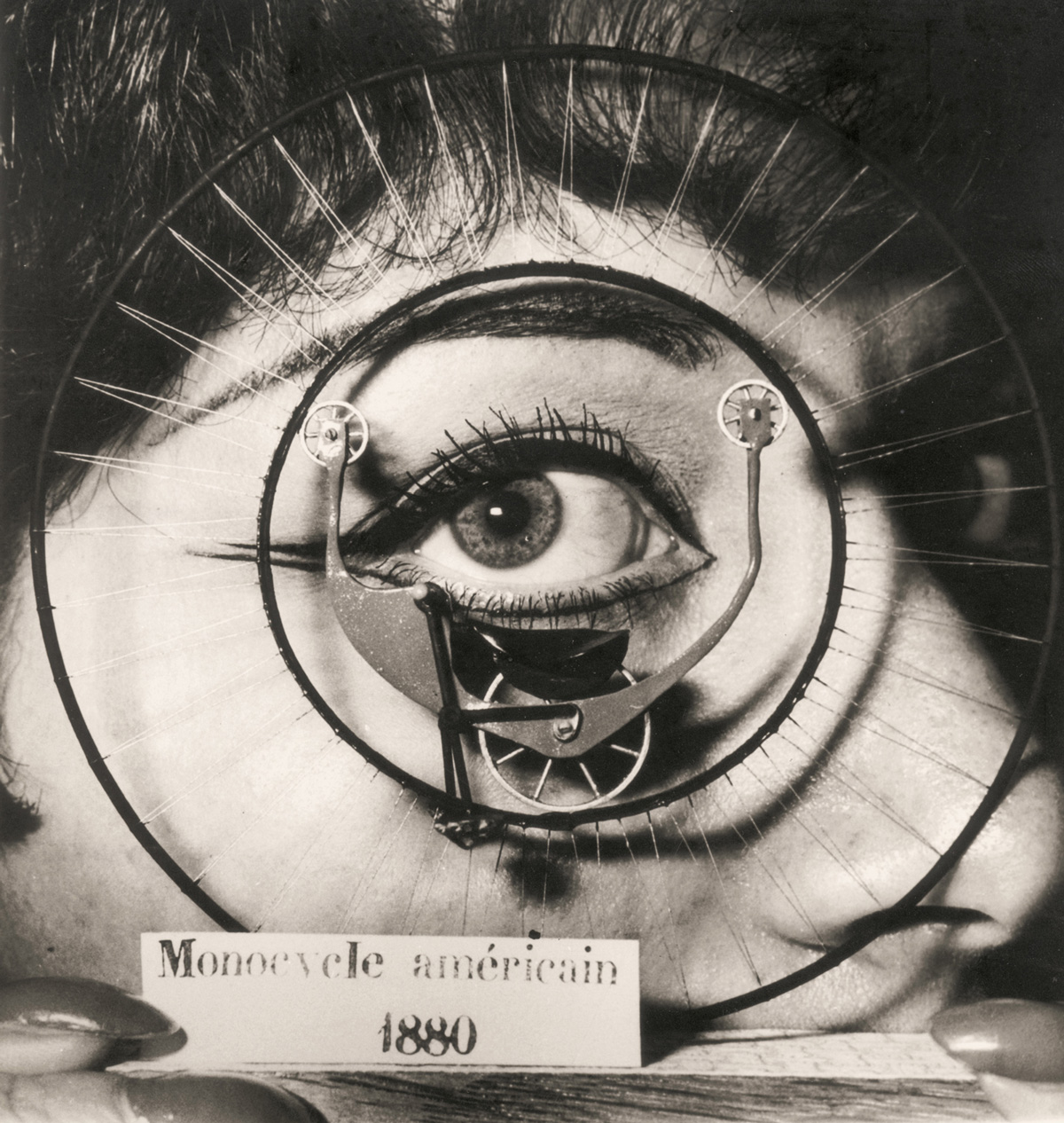

Rolling open with a satisfying whoosh, the solid overstuffed drawers would reveal upright cardboard files whose condition ranged from crispy brand new to disintegrating scraps. “Schauffler, Jr; William G. Col. Airforce D E A D 10/22/51,” for instance, on the Personality side; or, more desirable and in sync with my tastes, on the Subject side: “Toys: Historical,” “Models: Ships and Submarines,” or “Portugal: Industry: Misc.” There were “Hands,” “Magicians and Mind Readers,” “Brushes,” and “Monocycles.” Everything was broken down into a thousand, a hundred thousand, a million different categories, subgroups, subsets, and variations. There were wild unfulfilled notions that had been photographed in the planning, the making, the testing, or the aftermath; curious pursuits, causes, philosophies, social issues, ideas, and adventures I had never dreamed of.

Unlike most libraries, there wasn’t an official methodology, no Dewey Decimal System under which to organize these fragments. Instead, my research was governed by an accumulation of personal, unscientific categorizations devised by individual librarians that over the years had become the archive’s de facto filing, cataloging, and naming system. And therein lay the Library’s charm, a vagueness and lack of specificity perfectly appropriate to a reality full of messiness and confusion. Some of these ad hoc systems made sense and some were incomprehensible. For example, “Birds” had their own files as opposed to being included in “Animals.” “Fish” were separate too. Aren’t birds and fish animals? Why did there need to be a file for “Monocycles?” Couldn’t it have been included in the “Bicycles” file? Some seemed commonsensical, at least to me: “Storms: Hurricanes: Foreign: 1970” or “Movies: Props.” But “Sleep”? “Beauty Culture”? What did those mean? Pictures of people sleeping? And what, exactly, is “Beauty Culture”?

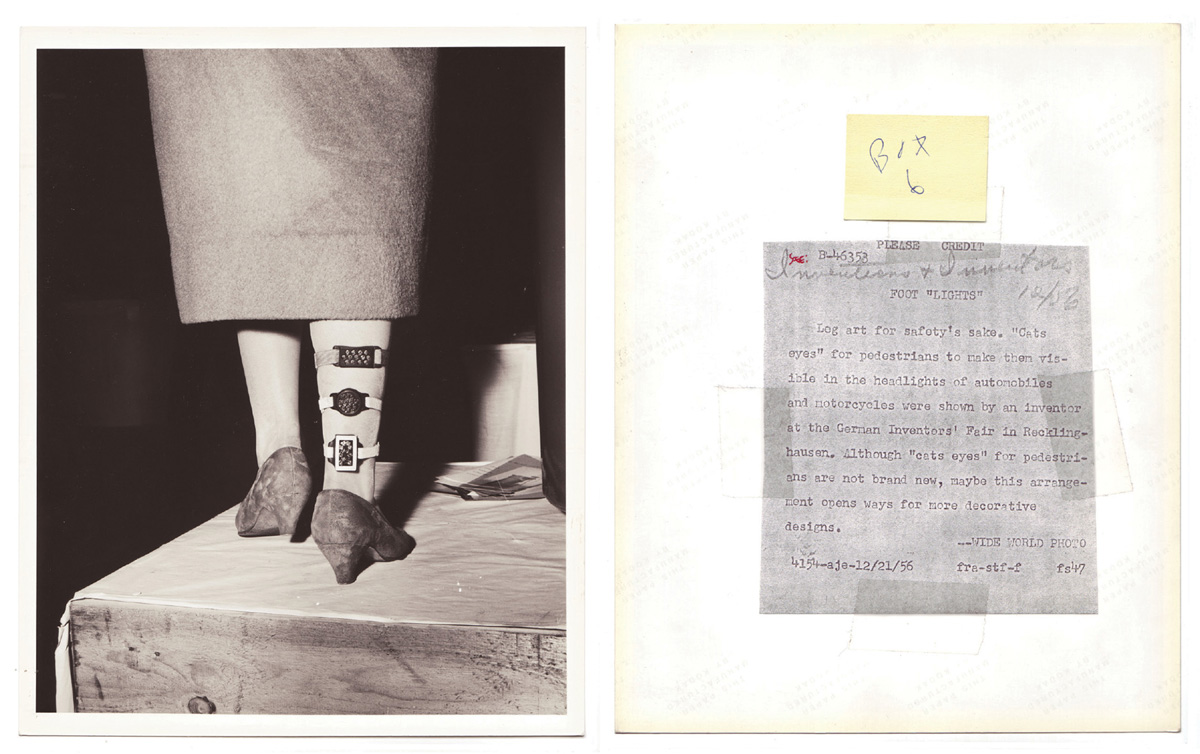

I wasn’t finding out about the World exactly, but it was certainly an education in how we act and present ourselves in the world (often with a lag of several decades, since the photos I liked were mostly drawn from the period between the 1940s and the early 1960s—the Golden Age). Running my fingers over the tops of files, I would stop at one like “Inventions and Inventors.” Jackpot. I was seduced time and again by the allure of that typewritten Courier font on those brownish yellow envelopes, the cryptic handwritten date and subject heading rendered in a cursive style no longer practiced except by retired librarians in old age homes. I would hold the negative up to the fluorescent light between thumb and forefinger: did it look like it might be part of my other, secret archive, that larger family of images that didn’t fit? A woman’s leg, standing on a bare platform, with odd bands like watches around her calves. An eldritch, disturbing picture. Then came the caption, which was at least half the fun. “Foot ‘Lights,’” read the headline, and an explanation: “Leg art for safety’s sake. ‘Cats eyes’ for pedestrians to make them visible in the headlights of automobiles and motorcycles were shown by an inventor at the German Inventors’ Fair in Recklinghausen.” The picture is dated “12/21/56.” Decorative jewelry-like reflectors that never really caught on, a piece of history—perhaps not significant, but who’s to judge?—gone missing.

“To possess the fundamental curiosity of the real explorer, who does not necessarily want to arrive at some goal but who is driven on and on, always eager to see the other side of the next hill, and only infinity is the end.” The quote, from the eighteenth-century adventurer Captain James Cook about exploring the far-off territories of the South Seas, is equally applicable to the Library, where the terra incognita is composed from the forgotten fragments of history. The examples depicted on these pages are just a tiny opening on a vast universe as seen by one besotted photo librarian under the spell of shorthand instructors, violins fashioned from Lumarith, monocycles américains, leg art, and square watermelons.

Jocko Weyland is the author of The Answer is Never: A Skateboarder’s History of the World (Grove Press, 2002) and has written for Thrasher, the New York Times, Busters, and other publications. He is the creator of Elk and an editor-at-large for Open City magazine.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.