Photoagentur Potemkin

Out of the picture

Adam Jasper

At the northern extremity of Bedford Avenue, in the largely Eastern European enclave of Greenpoint, Brooklyn, an unprepossessing shop sits facing McCarren Park. At first glance, it appears to be a typical small photo studio, a relic of the pre-digital era, the sort of place that promises one-hour developing and optimistic family portraits. In the window, pictures of smiling grandmothers and tennis stars jostle each other against a black velvet background, all of them slowly discoloring and warping in the light.

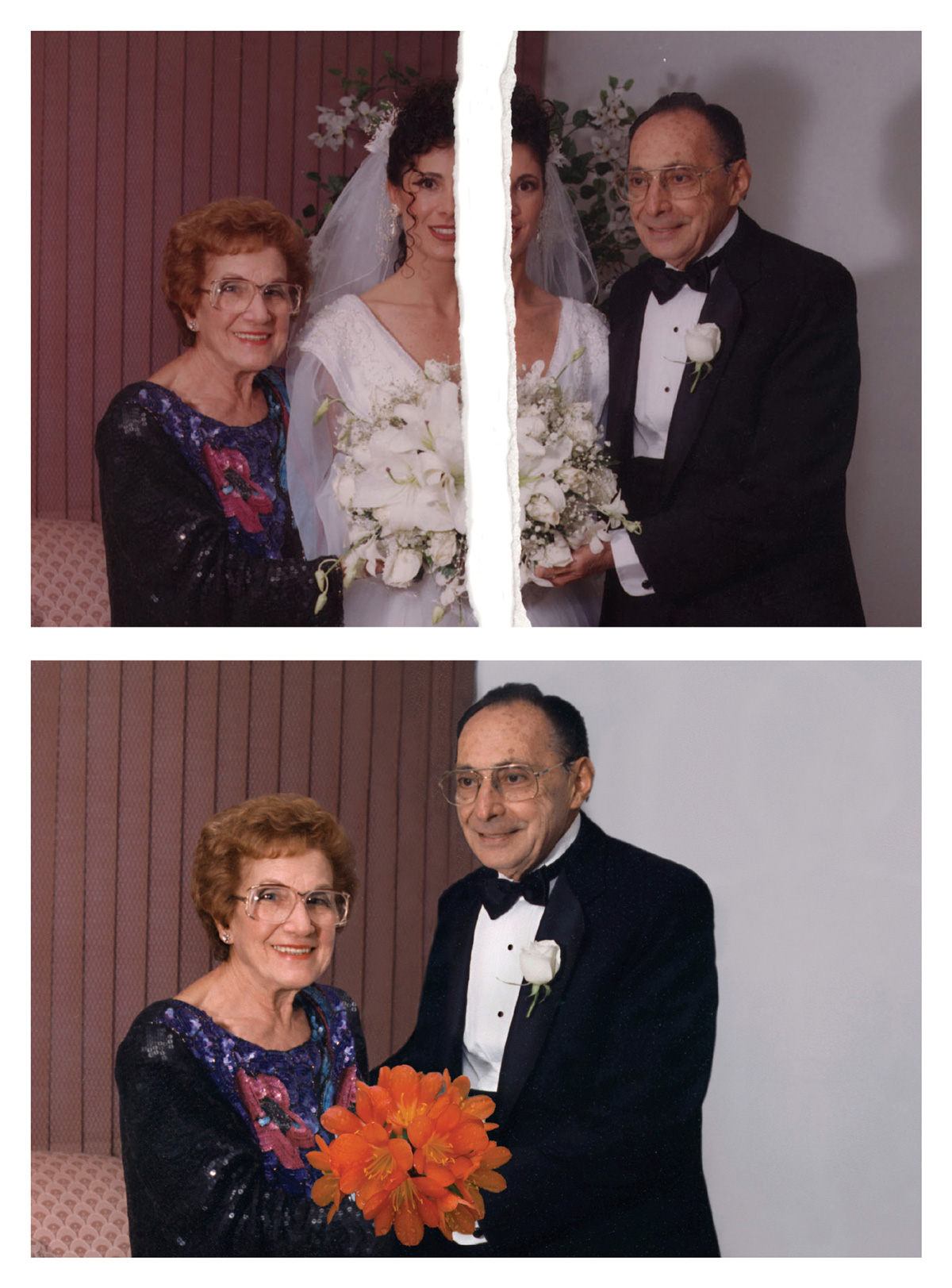

A second glance, however, reveals that not all the pictures are dusty or damaged, and that these recent additions are arranged in pairs—the flawed on one side, the perfected on the other. A small, stained, wartime passport image of someone’s grandma is enlarged and repaired to make a fine black-and-white portrait. Unnervingly, not only has the identity photograph been transformed into a portrait, but, via some strange necrocosmetics, the simple flannel shirt and overcoat in the original have been replaced by a starched white blouse and a jacket. The grandmother’s hair is fuller, and the “care lines”—visible even in the tiny smudged original—have been ironed out. A wedding photo of a young bride flanked by her two benevolently smiling parents is torn down the middle, vertically bisecting the bride. To its right, the image has been seamlessly rejoined, the reunited elderly couple now smiling over a large bouquet of purple orchids where their daughter once stood.

Where is the bride?

Marek and Eva Janikowski, the friendly couple who have run Marek Photo Services for over twenty years, are happy to comment on their window display. The smiling parents are not, in fact, the father and mother of the bride but her parents-in-law. The mother-in-law tore the picture in half after her son’s marriage disintegrated but she quickly realized that she had not only dismembered her former daughter-in-law, but also separated herself and her husband. What is joined in the house of God should not be torn asunder. Perturbed, she took the photograph, now fifteen years old and not unflattering, to be repaired. With the prodigal daughter replaced by the orchids, the wedding photo now celebrates the older couple’s anniversary instead.

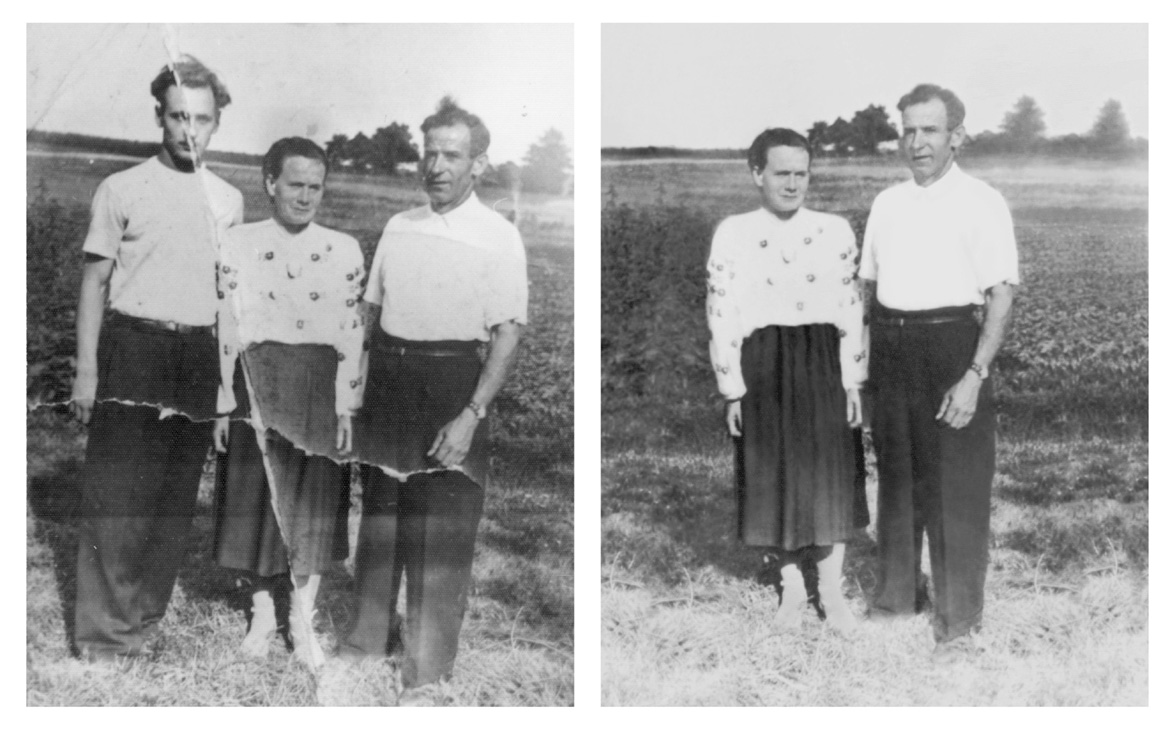

That the bisected bride is not an isolated incident becomes clear on entering the shop. A creased black-and-white image shows a young man and his two elderly parents in front of a farm in eastern Poland. Next to it, the same image appears with the young man removed, a perfect void of mud and horizon where he previously stood. His sister had emigrated to America decades before and taken the first image with her as a memento. On the death of her parents, her brother refused to hand over her share of the farm on the pretext that she was, as an American citizen, prosperous enough. She reacted by having him expunged, from the picture and from her memories.

In some cases, the act of erasure seems much sadder than the event that motivated it. In one heavily abraded photograph, a mother stands with her two daughters on the day of their first communion. It is somewhere in the old country, sometime in the late 1940s. The year is uncertain, but from the bouquets the girls are holding, one suspects that it is spring. The two girls are wearing prim, white communion dresses, the mother an embroidered shawl. One of the girls, pretty and alert, is shod in marvelous, white patent leather shoes. Round-toed kitten heels, they would now be called, with a strap over the foot. On her sister’s feet, in an injustice that remains incomprehensible to this day, are dark, scuffed farm shoes, not buckle-ups, and in all likelihood laced with string. Many decades pass, and the sister less favored brings the photo to Marek Photo Services. She is now over eighty. She points to her sister and says, “She is dead, take her out. Take her out, but give me her shoes.” In the edited image, her sibling has vanished, and the surviving sister’s ugly black boots have been replaced by the marvelous white shoes. The mother now looks even more confiding—her gaze now settles more directly on the viewer—and the unloved daughter stands unsteadily on her new feet, looking as consternated as ever before. White shoes or not, the unlucky child will always be trapped in that photograph, but her older self can now catch her mother’s glance without her sister in the frame.

The power to take revenge even upon the dead is normally considered the prerogative of despots. David King’s 1997 book, The Commissar Vanishes, documented the many ways in which the victims of Stalin’s purges were expunged from the public records, their images removed with scissors, scalpels, and air brushes from the documentary photographs of events. The most famous instance of this policy in action was the disappearance of Trotsky from Lenin’s side in photographs of the revolution in newspapers, university archives, and school textbooks across the Soviet Union.

If the power to change the past via its image is a distinguishing feature of totalitarian regimes, at what point did the instruments of dictators become the weapon of choice for family feuds? Or, inversely, were Stalin’s actions themselves the extension of accepted private practice onto a public stage? The photographs from Marek Photo Services suggest a new interpretation of Stalinist erasure. As King shows, the erasures were not perfectly conducted, and nor were they meant to be. It is often possible to see evidence that the photos had been tampered with, the trace of removal signifying the power of the sovereign. While the identities of those purged were erased, the memory of their purging had to be preserved as a warning. In this way, the purges functioned as public show trials, but they went one step further insofar as the erasures required the active participation of the public itself, who clipped or inked out the missing person from their documents, photographs, books, and archives. Even schoolchildren were inducted into the ritual, as they scratched out the faces of purged historical figures from their textbooks on their teachers’ instructions. This large-scale complicity is what makes it terrifying—and modern. We might like to think that mass complicity is no longer possible, but the customers of Marek Photo Services show that securing our willingness to participate in such national rituals may be less difficult than we might believe. As it turns out, the best feuds are a family business.

Since this article was written, Marek Photo Services has closed its shop, instead offering its services online at www.photoprofix.com [link defunct—Eds.].

Adam Jasper is completing his doctorate in art history and theory at the University of Sydney on minor aesthetic categories, such as kitsch and the gross. At the time of writing, he is in the Philippines, attempting to get into prison for Vice magazine.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.