Perspective Correction

The beguiling stagecraft of American politics

Greg Allen

When donor disputes and protests from neighboring monks upset the original plan for a dome over the nave in Rome’s Church of Sant’Ignazio, the Jesuits turned to one of their own: the architect, painter, and stage designer Andrea Pozzo. Already renowned for his work in the illusionistic architectural painting style known as quadratura, Pozzo created a masterpiece of the High Baroque era: a fantastical painting on canvas seventeen meters across, depicting an illusory, coffered dome and a towering architecture open to the heavens. Foreshortened figures from the life of St. Ignatius flew among columns and arches rendered in severe perspective. The pictorial distortions resolve to a single vantage point below, the punctum oculi, which Pozzo marked with a disc of yellow marble embedded in the church floor.

Two key elements of Pozzo’s Sant’Ignazio—the severing of the connection between the facade, or the presented exterior, and the interior, and the imperative of setting the punctum oculi—are core to Gilles Deleuze’s definition of the Baroque and its implications for “the new optical model of perception.”[1] In a perspectivist system, power resides in controlling the point of view, which is “a condition for the manifestation of reality.”[2]

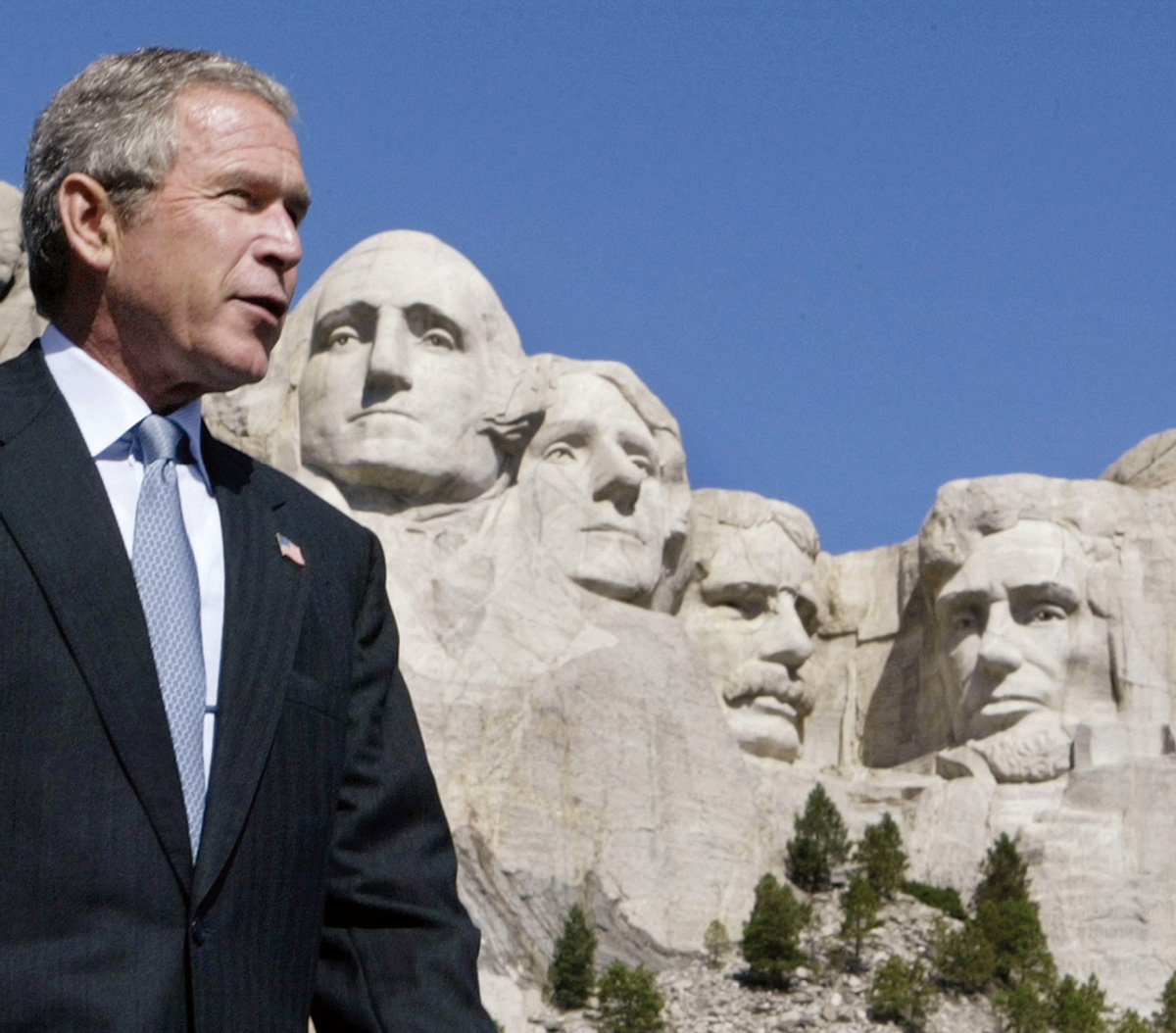

These same Baroque tenets characterize the image-making strategy of another organization that mingles the spiritual with globe-spanning secular authority: the White House of George W. Bush. In what may be deemed “a new optical model of governing,” the Bush Administration have deployed sophisticated stagecraft and visual tricks in a far-sighted and unprecedentedly assertive approach to shaping media coverage and to disseminating their desired messages on a daily basis.

In explaining the strategy for managing the White House press operations in early 2001, presidential adviser Karl Rove told Professor Martha Kumar of Towson University, “What you want to do is to set up the picture so that if the television sound is turned down, that it gets across what it is the President wants.”[3] Kumar examined the White House’s three-tiered communications management structure: strategists such as Rove and longtime Bush confidante Karen Hughes map out the desired messages or “thematics” several months in advance; next, operations people scout out events, locations, and commemorations to serve as suitable venues for each thematic; finally, implementers prep and stage the event, paying attention to details grand and minute with an eye towards crafting not the event itself but the precise images and sound bites the White House press corps would produce as they cover it.[4]

The chief implementer, and thus the man responsible for staging and constructing most of the images of George W. Bush’s first six years as president, was Scott Sforza. (Sforza reportedly left his White House position in 2006. Attempts to contact him for this article were unsuccessful.) A former producer for ABC News who joined the Bush campaign in 2000, Sforza’s stagecraft leveraged his own television production expertise and his understanding of the conventions of editors, producers, camera crews, and photographers. Sforza and his advance team would optimize each venue on the President’s schedule for image production, pre-composing their thematic-driven shots by using props, lighting, and visually arresting backdrops, dubbed “Sforzian Backgrounds” by the New York Times’ reporter Elizabeth Bumiller.[5]

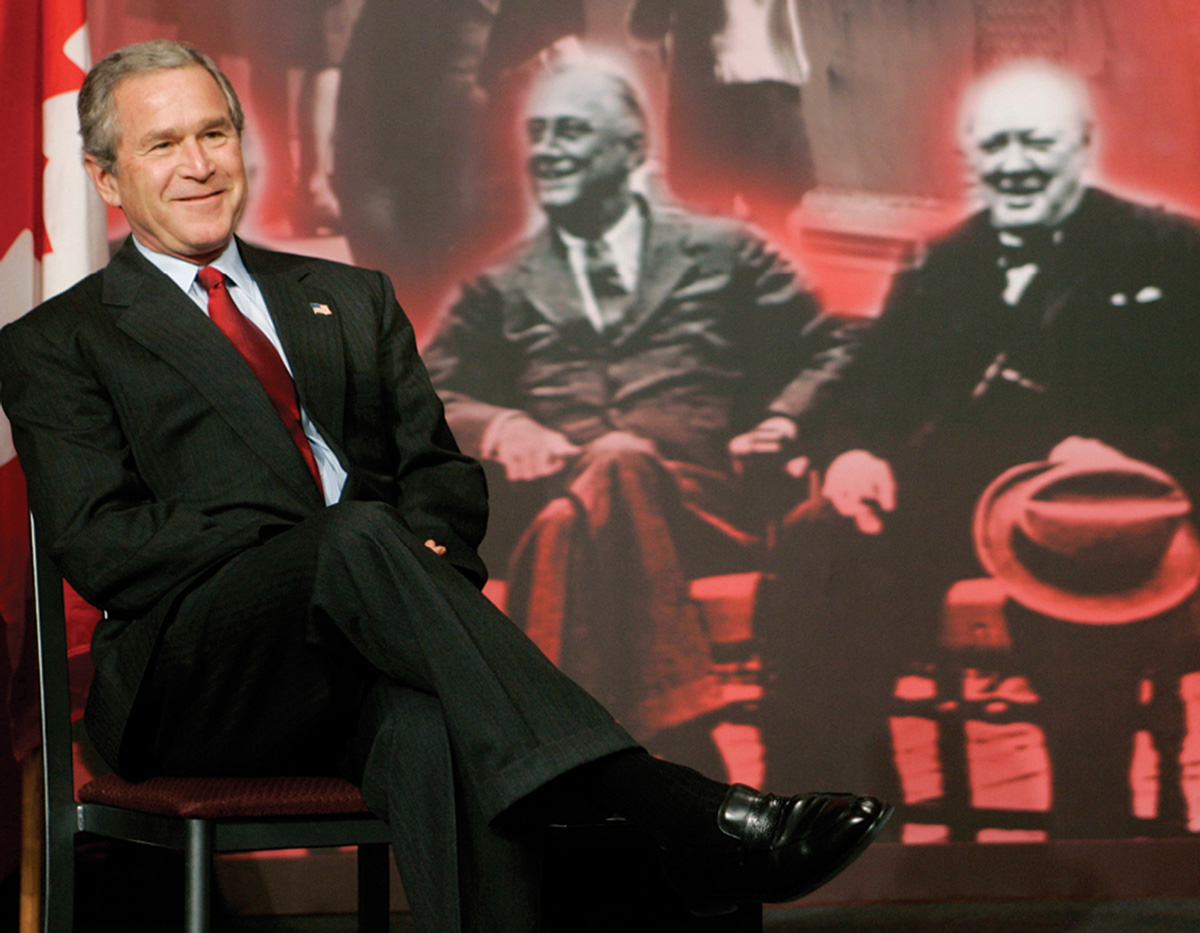

Like the most controversial of Sforza’s productions—the “Mission Accomplished” banner on the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln under which George W. Bush prematurely declared victory in Iraq—many of his PowerPoint-inspired backdrops feature slogans and maxims in clichéd typefaces: “Strengthening America’s Schools” on a faux chalkboard; “Plan For Victory” in beveled, heraldic gold. Some backdrops included symbolic personages, such as the soft-focused figures of Winston Churchill or Ronald and Nancy Reagan, which were positioned so as to hover behind Bush’s shoulder, like the beneficent presence of the dearly departed in the double-exposed images of nineteenth-century spirit photographer, William H. Mumler. (It should be noted that as this essay goes to print, Nancy Reagan is alive and still enjoys good health.) Sforza also deployed real people as human wallpaper by carefully lighting sections of the auditorium, or by positioning blocks of audience members on or behind the podium. The technique is particularly noticeable when Bush addresses a uniformed military audience or the non-white beneficiaries of some governmental largesse, such as African-American community development groups in Philadelphia or refugees from Hurricane Katrina. At one event, the Republican VIP supporters in the background were instructed to remove their ties so as to appear “ more like the ordinary folk the president said would benefit from his tax cut.”[6]

Success in achieving a Deleuzian “manifestation of reality,” or the dissemination of the White House’s desired thematic, necessitates controlling the point of view, or the “geometry of perception.”[7] For Sforza and his fellow White House implementers, however, the target is not any punctum oculi, but the positions and angles from which the journalists’ cameras would be trained on the presidential spectacle—a punctum lenticulae.

Manipulating the punctum lenticulae does not involve coercive or restrictive techniques that might risk raising the ire of journalists. Instead, the combination of Sforza’s own understanding of editorial conventions of utility and aesthetic interest, the pressure on journalists on location to “get the shot,” and the production design exertions of the White House advance team enabled something short of collusion, but akin to the relationship between a magician and his anticipatory audience. Deleuze couched this type of interaction in musical terms; the prescribed, synchronized accord between the perceived subject and the viewer within the closed system of production is “concertation,” or acting “in concert.”[8] And the end game of concertation is “harmony”: for the illusionist’s audience, this means astonishment, and for the photographer, “getting the shot.”

The shift to punctum lenticulae is not trivial. The Dutch conceptual artist Jan Dibbets, for example, exposed the distortions of the camera’s monocular point of view as it transmutes three-dimensional space onto a two-dimensional picture plane. In his Perspective Correction series of the late 1960s and early 1970s, Dibbets created trapezoids in physical spaces—his studio, on grassy fields, against walls—of such dimensions that, when photographed from a pre-calculated vantage point, they appeared as non-perspectival squares. The artist’s “corrections” at once highlight the camera’s susceptibility to premeditated manipulations of its vantage point and “undermine our confidence in the transparency of the photographic index.”[9]

Such self-criticality is all but invisible, however, in the Sforza-inflected images executed by photographers from the major news organizations and wire services. Editors, producers, and journalists have not been particularly forthcoming in acknowledging to their own viewers, the media-consuming public, the degree to which the object of their reporting dictates its content and composition. To the extent they accede decisions of framing and the inclusion of content, they perform as a sort of visual ventriloquist for the White House’s own chosen thematics.

It falls, then, to observers outside the closed subject-viewer system that is the White House press pool (and the mainstream domestic television and print media for which it is proxy) to expose the mechanisms and calculations of the Sforzian geometry of perception. These observers are not subject to the same demands and conventions as the major media; the shots they need to get are different. One unlikely category of observers at a distance actually reside within the ropelines. Official White House photographers enjoy greater freedom of movement at presidential events, and from their vantage points “backstage” and in the figurative “control room,” they can capture the extent of Sforza’s perspectivist manipulations, limning the edges and positions of backdrops, and producing aesthetically suboptimal but information-rich, contextualized images. These pictures are published in official channels such as the White House website, where their inadvertent revelations of Sforzian stagecraft apparently do not create sufficient dissonance to wake the censors. (One notable exception: all photos of the “Mission Accomplished” event have been scrubbed from the site.)

Independent and foreign reporters also often resist the Baroque manipulations of the official points of view. The intended thematic of the president’s four-hour visit to Mongolia in November 2005 was to let Bush stand with other brave warriors in the Coalition of the Willing. The photos taken by Dutch journalist Iwan Baan tell a somewhat different story. Invited by the president of Mongolia, Nambaryn Enkhbayar, to cover the first visit of a sitting US president to the vast, impoverished country, Baan was unconstrained by conventional editorial shotlists or dictates. His photographs of Bush’s visit to an archetypal nomad family forefront the incongruity and absurdities of the presidential photo-op process—staircases and Porta-potties dropped into the middle of a vast Mongolian landscape, and warriors on horseback running alongside the presidential convoy bristling with antennas. Similarly, when Bush took the stage to praise the Mongolian parliament as a model of nascent democracy, a wide shot revealed the dingy auditorium of Ulaanbaatar High School, unadorned save for the isolated Sforzian backdrop panels and a pair of potted ferns.

The compositional power of the White House’s meticulous stagecraft can also be exposed by its conspicuous absence. When President Hu Jintao visited the White House in April 2006, US media reports focused on the importance of symbolism to the Chinese and the Bush Administration’s decision to not grant the occasion official “state visit” status. Although the crowds of invited guests looking on as drum-and-bugle corps in 1776-style tri-cornered hats paraded across the South Lawn of the White House might have imagined diplomatic pomp ruled the day, the photo and video images of President Hu’s otherwise elaborately staged reception betrayed no trace of Sforzian pre-composition. Instead of having vantage points that captured the statesmanlike grandeur visible from President Hu’s vantage point, press photographers were stationed at an oblique angle to the rather barebones dais where the two presidents stood and were thus precluded from getting an easy, imposing shot with the White House portico in the background.

But the journalists did not lack for newsworthy images. During Hu’s speech, a Chinese reporter from a Falun Gong newspaper unfurled a protest banner and began shouting from her perch among the television cameras. (Despite a history of disrupting official events, she had somehow received press credentials from the White House.) After several minutes’ delay, Secret Service agents frogmarched the protestor away; their route passed directly in front of the assembled media. And photographers’ sideways view of the dais proved auspicious for capturing a shot of a different sort: when President Hu seemed about to flub his stage directions by going down the wrong stairs, Bush unceremoniously grabbed him by the suit sleeve and gave him a corrective tug, in case there was any doubt about who was running the show.

The conflux of conspiratorial camera angles and Chinese diplomatic affronts recalls an incident discussed in “The Image-World,” the final essay in Susan Sontag’s 1977 book, On Photography. In 1972, to commemorate the restoration of diplomatic relations between Italy and the People’s Republic of China, Premier Zhou Enlai invited the director Michelangelo Antonioni to travel the country and shoot a film. By the time the four-hour documentary, Chung Kuo Cina, was released, however, the political winds had changed, and the Communist Party, under the sway of Mao Zedong’s wife, Jiang Qing, condemned it as an “anti-China film.” Tens of millions of people were organized into repudiation sessions, where the particulars of Antonioni’s sympathetic, naturalistic, slice-of-Cultural-Revolutionary-life movie were criticized at length. (The film was banned and not screened in China until 2004.) Among Antonioni’s most egregious cinematic crimes, Sontag explained, was his manipulative camera placement. In one scene, a Chinese newspaper complained, “The camera was intentionally turned on this magnificent modern bridge from very bad angles in order to make it appear crooked and tottering.”[10] Sontag attributed this critique of photographic “tricks” to China’s essentially premodern notion “about the moral order of space” that favors images created “from the point of view of a single, ideally placed observer” over the “photographic dismemberment of reality” performed by, say, an edited montage of long, establishing shots and revealing close-ups.[11] It was an unsophisticated, even uncivilized, visual taste that was, as she put it, characteristic “of those at the first stage of camera culture.” By her unironic use of subjects such as “we,” “they,” and “the Chinese,” Sontag’s essay exults in a Cold-War-hardened confidence that American culture and politics were defined in diametric contraposition to the totalitarian Other:

Photography for us is a double-edged instrument for producing clichés (the French word that means both trite expression and photographic negative) and for serving up “fresh” views. For the Chinese authorities, there are only clichés—which they consider not to be clichés but “correct” views.

In China today, only two realities are acknowledged. We see reality as hopelessly and interestingly plural. In China, what is defined as an issue for debate is one about which there are “two lines,” a right one and a wrong one. Our society proposes a spectrum of discontinuous choices and perceptions. Theirs is constructed around a single, ideal observer; and photographs contribute their bit to the Great Monologue.[12]

It’s a worldview that, from this observer’s angle, at least, the Bush Administration has rendered quaint and obsolete.

- Gilles Deleuze, The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque [1988], trans. Tom Conley (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1993), p. 21.

- Ibid.

- Martha Kumar, panel transcript, “The George W. Bush Presidency: An Early Assessment,” 25–26 April 2003, Woodrow Wilson School, Princeton University, p. 5. Available at wws.princeton.edu/bushconf/Transcript%204-26-03.pdf [link defunct—Eds.].

- Ibid., p. 3.

- Elizabeth Bumiller, “Keepers of Bush Image Lift Stagecraft to New Heights,” The New York Times, 16 May 2003, p. A1.

- Ibid.

- Deleuze, p. 124.

- Ibid., p. 21.

- Lucy Soutter, “The Photographic Idea: Reconsidering Conceptual Photography,” Afterimage, vol. 26, no. 5, March–April 1999, pp. 8–10.

- “A Vicious Motive, Despicable Tricks: A Criticism of M. Antonioni’s Anti-China Film ‘China,’” Peking Foreign Language Press, 1974; quoted in Susan Sontag, On Photography (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1977), p.171.

- Sontag, p. 170.

- Ibid., p. 173.

Greg Allen is a writer and filmmaker in New York City and Washington, DC. He contributes to the New York Times and publishes two blogs: “the making of” at www.greg.org, and “the weblog for new dads” at www.daddytypes.com. His celebrity parenting handbook will be published by Riverhead Books.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.