Object Lesson / Lost Object

What can be said about what Breton loved?

Celeste Olalquiaga

“Object Lesson,” a column by Celeste Olalquiaga, reads culture against the grain to identify the striking illustrations of a historical process of principle.

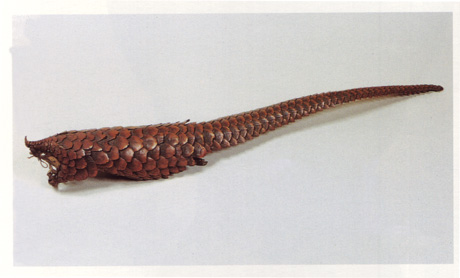

The event is the famous auction of André Breton’s collection in Paris during the spring of 2003, a complete scandal: the dispersion of one of the most astonishing modern collections, put together by the father of surrealism over half a century of roaming flea markets, auctions, artists’ ateliers, and the world at large. Rather than a classic “cabinet of wonders” (whose study has become so fashionable these days), Breton’s collection may be considered a “cabinet of wanders.” Beyond the apparently random selection and fortuitous disposition of natural, artificial, and in-between objects (objet trouvés, objets interpretés, objets mathématiques, objets naturels, objets ready-made, objets mobiles…), staple processes for assembling any curio cabinet worth its name, the collection that Breton amassed from 1922 to 1966 attests to his multiple interests and restless spirit, to the capacity to change (political alliances, love partners, objects) in order to remain true to oneself, and, above all, to a subversive desire that chose representation as its privileged territory of combat.

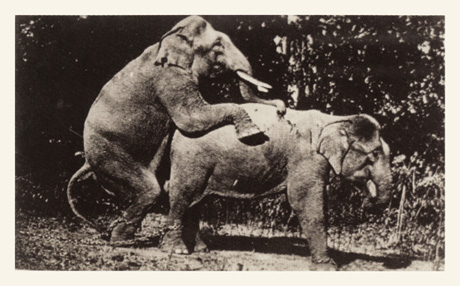

At once departure and landing point, refuge and escape, Breton’s collection was a “magical continent” that contained his heart and mind in fragments, much like a domestic shrine where relatives’ photos are placed side by side with saints’ effigies and votive objects, except that in Breton’s case, the latter two were replaced by the quintessential artists of his time— European and “primitive” alike—and the residues of an organic universe animistically invested by both Western and non-Western cultures: De Chirico and Ernst alongside Hopi dolls and Polynesian fetishes, insect collections and African totems, a Victorian bird-tree and a photograph of Elisa Claro (his third wife, whom he met during his five-year World War II exile in New York). In the midst of it all, Breton himself, sitting at his desk like a ruling divinity for whom the whole universe is at hand.

The object of my desire at the auction is a 10" x 15" glass box containing eighteen roundish stones with slight starry marks: fossilized sea urchins whose spiny carcasses were gradually polished by water and time—relics of a fragile existence whose paradoxical endurance elicits the kind of daydreaming cherished by surrealism. My fascination with them is partly about time, a time that never ceases to roam, a time continually seeking its ultimate resting place, lost time; perhaps this is the same or du temps, or “gold of time,” that Breton declared in his proposed epitaph to be the object of his quest. “What can be said about what we love and how can we make others love it?,” he asks in the catalogue of a 1939 exhibit on Mexico. By applying what he elsewhere refers to as the “will to objectify” (volonté d’objectivation), which grants objects an autonomous existence free of intellectual abstraction and practical use and yet filled with the intensity of whatever made us experience them as unique and alive. Breton warns against fetishizing found objects, however, claiming they are but a means to an end—the experience they furnish. Yet it is hard to avoid doing so, since objects incorporate emotions as readily as people, providing the basis for what psychoanalysis was articulating during Breton’s time as “object relation,” or the infinite ability of human beings to make others—creatures or things—the vehicles of fantasies.

Like writers submerged amid piles of books, or antiquarians concealed among their precious items (how quickly can one find antiquarians in their stores? They seem to have the uncanny ability to merge with their merchandise…), true collectors live for their objects in a way perhaps only matched by the very first object relationship: fusional love. No boundaries, just an endless projection in a microcosm that acts like a hall of three-dimensional mirrors.

Nowadays, Le mur Breton at the Centre Georges Pompidou is all that is left of the magnificent collection that filled Breton’s atelier at 42 rue Fontaine at the foot of Montmartre, and that many believe should have been designated a national heritage, a cause for which Breton’s daughter, Aube, who donated the objects to the museum, struggled long and hard. The “Breton wall”—consisting of all the objects that the writer had carefully assembled on the wall behind his desk—was recreated for the reopening of the museum in 2000 as a memorial to this unique wall and as a tribute to objects, as well as to the man and to the movement he so acutely embodied.

Breton saw modernity’s attempt to rationalize things and render them functional as provoking a crisis of the object. In “Crise de l’objet” (1936), he writes: “It is important to strengthen at all costs the defenses which can resist the invasion of the feeling world by things that men use more out of habit than necessity. Here as elsewhere, the mad beast of custom must be hunted down.” In this sense, and despite all his avant-gardism, he was an avowed Romantic, opposing emotion to reason. But by the time Breton wrote this, objects had already joined battle with modernity, and lost. They had ceased to be, as Walter Benjamin could see in 1927, within the grasp of dreams, entering instead the phase of their industrial and capitalistic disintegration. They had become dust: “No one really dreams any longer of the Blue Flower,” writes Benjamin in his short text “Dream Kitsch.” ”The dream has grown gray. The gray coating of dust on things is its best part. Dreams are now a shortcut to banality. Technology consigns the outer image of things to a long farewell, like banknotes that are bound to lose their value.”

During the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, dust was kitsch, a new object domain where things could still survive as ruins of themselves and of the dreams that created them. But in the third millennium, dust has been blown away by the only force capable of dispelling concrete reality and its residues: the imaginary, in the form of virtual reality. Intangible and fantasmatic, objects now inhabit a parallel world whose striking similarity with the unconscious can render it either titillating or frightening, according to where one stands on the technological divide.

How Breton would have faced this almost-literal version of the imaginary, where everything and everyone is dematerialized to the limit is anyone’s guess. His was a struggle against the symbolic order that took place within the object itself, not outside it: “The total revolution of the object,” he said, consists in turning it away from its end (the “objet ready-made”), in showing how it is affected by natural or unnatural contingencies and allowing for the ambiguity that results from a casual encounter (the objet trouvé), in enabling the widest possible readings (the objet interprété), and in assembling disparate elements without an ultimate purpose (the objet surrealiste, properly speaking). “Disturbance and deformity are sought for themselves, in the understanding that one cannot expect anything from them but the continuous and revitalizing correction of the law.”

The scene is l’Hôtel Drouot, one of those horrifying buildings that make one wonder how Paris, the first modern capital and a city so proud of itself, could so diligently avoid the allure of modernist architecture and go from the nineteenth to the twenty-first century with just a skip and a hop of Art Deco and several splashes of 1970s sterile functionality, the only style ever worth demolishing. The time: 2:30 PM. A close inspection of Breton’s collection two days before had designated the sea urchins as my potential prey. My only hesitation is about their surface, too smooth for the ruin they ultimately are. The auction gets under way: lot #3140 comes, and goes. I sit there, in the middle of the crowded red room, stunned by my indecision, telling myself how the urchins were not textural enough and that my finances would have collapsed. I know, as I stand and leave a place that has suddenly become entirely superfluous, that the small glass box and its spineless treasures will prick at me for the longest time.

Celeste Olalquiaga is the author of Megalopolis: Contemporary Cultural Sensibilities (University of Minnesota Press, 1992) and The Artificial Kingdom: A Treasury of the Kitsch Experience (Pantheon, 1998). She is currently writing a book on petrification. For more information, visit celesteolalquiaga.com.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.