Mont Blanc Montage

Up the mountains, in fiction and in fact

Colby Chamberlain

“I think it may be assumed that most of us here know something about traveling,” begins Charles Dickens.[1] The scene, from December 1854, is the annual dinner commemorating the founding of the Commercial Travelers’ Schools. Dickens is playing host and introduces the evening’s honored guests: “So many travelers have been going up Mont Blanc lately, both in fiction and in fact, that I have heard recently of a proposal for the establishment of a Company to employ Sir Joseph Paxton to take it down,” he says, referring to the architect of the Crystal Palace, the celebrated steel-and-glass edifice that had housed the 1851 Great Exhibition. “Only one of those travelers, however, has been enabled to bring Mont Blanc to Piccadilly.”[2] That particular feat—accomplished through pluck and charm, not to mention panoramas, Edelweiss, wine bottles, St. Bernards, cannon fire, and musical routines—was the work of Albert Smith.

The son of a surgeon from the village of Chertsey, Smith was a medical student at the Hotel Dieu in Paris when he made his first steps towards a literary career, submitting to the Mirror a humorous series of “Sketches in Paris” in 1838. Becoming an early contributor to Punch starting in 1841, an editor of Puck in 1844, and a founding editor of The Man in the Moon in 1847, Smith demonstrated a talent for lighthearted social satire, his greatest literary successes being “natural histories” that vividly described stock characters of the London scene: The Gent, The Ballet-Girl, The Idler Upon the Town. Also a novelist, lyricist, and playwright, he adapted several works by Dickens for stage, including The Cricket on the Hearth. Smith also became fast friends with P. T. Barnum during the circus impresario’s European tour and wrote the playlet Hop o’My Thumb for Barnum’s biggest star, the Lilliputian performer Tom Thumb.

These diverse literary pursuits notwithstanding, the persistent theme of Smith’s work is travel. In 1849, he quit his editorial responsibilities to take a trip to Constantinople and upon his return in 1850 presented The Overland Mail, “a Literary, Pictorial, and Musical Entertainment.”[3] For the purpose of illustration, Smith devised an early version of the moving panorama, a series of drawings stitched into a single long scroll that shifted from scene to scene as he narrated his journey. In reviews of The Overland Mail, this method of presentation received praise for its combination of “the instructive diorama, which has of late, become so much the rage, and the humourous song and character sketch,” as did the lightweight charm of Smith himself.[4] “Verily, a pleasant evening may be spent in the company of Mr. Albert Smith, who, if not very instructive, is very entertaining.”[5] A forerunner of the vacation slideshow, the format’s itinerary of images permitted Smith to skip nimbly among destinations, shuttling from anecdote to anecdote.

The Overland Mail fared well enough to merit a second season, but its audiences thinned when in May 1851 Paxton’s Crystal Palace first opened its glass doors. The Great Exhibition was nothing less than a new way of experiencing the world: a gathering of objects, representing the industrial and artisanal accomplishments of all nations, collapsed into a single sparkling setting. Attracting some six million visitors during its run, the exhibition was both reason and inspiration for Smith to raise his entertainment to a new level: in August he announced his intention to climb Mont Blanc. When told by a friend that his physique was “rather heavy for a mountain climber,” Smith replied, “Never mind ... Pluck will serve me instead of training; and I haven’t the slightest fear.”[6] The next morning, he and the scene-painter William Beverley departed for Chamonix, the small French town at the base of Europe’s highest peak.

The story of Smith’s ascent of Mont Blanc is a singular contribution to the lore of mountaineers. He had read the narratives of Alpine climbs as a child and was knowledgeable enough to summarize them in a bit of light verse written for Bentley’s Miscellany in 1841. Entitled “Ascents of Mont Blanc” and set to the air of a popular tune, the rhyme surveys the major figures in Mont Blanc’s history: Jacques Balmat, who completed the first successful ascent in 1786; Swiss aristocrat Horace-Bénédict de Saussure, who “we’re told / climbed in a full suit of scarlet and gold”; John Auldjo, who gained fame though his combined knack for mountaineering and publishing. After scanning a wide range of noted explorers, the ditty ends with an unexpected twist:

Full forty gentlemen wealthy and bold,

Have climbed up in spite of labour and cold;

But of that number there lives not one,

Who speaks of the journey as very good fun.[7]

Preoccupied with recording scientific observations or grasping at the sublime, the mountaineers of Mont Blanc, Smith argued, paid insufficient attention to merriment—a deficiency he would handily overcome.

In the written account of his journey, published in book form in 1853, Smith displays a determination to reach the top while also relishing the climb. Upon arriving in Chamonix, Smith pooled his resources with three gentlemen staying at his hotel who also intended to make the ascent. Together they enlisted no fewer than twenty guides and twenty porters to shoulder a staggering quantity of provisions: sixty bottles of table wine, six of Bordeaux, two of champagne, ten cheeses, twenty loaves, four legs of mutton, eleven large fowls, etc. The ledger marches steadily on, tethering a test of endurance to an exercise in consumption. Smith comments sparingly on the arduous passages of the climb in favor of the convivial moments afforded to such a large and well-lardered party. Arriving amid the glaciers by late afternoon, the party struck up an impromptu “high festival” and requisitioned the icy landscape for fairground competition: “A fine diversion was afforded by racing the empty bottles down the glacier. … Whenever they chanced to point neck first down the slope, they started off with inconceivable velocity, leaping the crevices by their own impetus, until they were lost in the distance.”[8]

The expedition’s arrival at the summit prompted a near-simultaneous discharge of champagne corks on high and cannon fire below in Chamonix, where the citizens had spied the climbers by telescope. Descending rapidly—“sliding, tumbling, and staggering about … sitting down at the top of the snow slopes, and launching ourselves off, feet first”[9]—Smith and his compatriots returned to a town transfixed and transformed by their achievement: “The whole population was in the streets, and on the bridge,” Smith writes, “the ladies at the hotels waving their handkerchiefs, and the men cheering.”[10] Congratulations, however, were not quite in order, as the true accomplishment was yet to come. Smith had made a perilous ascent for the most curious of motives—“Not for the fun of the thing,” as Harper’s put it later that year “but for the fun of telling it.”[11]

• • •

Seven months later in March 1852, Ascent of Mont Blanc opened at the Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly. William Beverley painted a series of large scenic views that, when pieced together, formed a single moving panorama similar to the one employed for The Overland Mail. Smith himself stood upon the stage behind a lectern speaking in tandem with the changing vistas and occasionally breaking into song, sharing scraps of the hurdy-gurdy music he had learned from his Alpine guides, or presenting original compositions. Like his “natural histories” of the 1840s, these songs were light satires of English society, in particular the tourists he had encountered en route to and from Chamonix—the elderly dowager constantly losing her luggage, the young gentleman struggling with a French phrasebook to order a meal. Just as he claimed for his climb nothing more grandiose than the enjoyment of an Englishman abroad, however, Smith did little to differentiate himself from these hapless travelers. Rather, he played simultaneously the role of lecturer and touring companion, permitting his audiences to imagine themselves as tagalongs to his expedition. “The whole was highly interesting, and thrown off in a genial mood … and full of bonhomie,” read the review in the Illustrated London News, “while the vivacity of the speaker never wearied either himself or his hearers. The performance must become highly popular.”[12]

And highly popular it became, quickly earning back Smith’s initial investment (not to mention the ballyhooed expense of his climb). For the second season, Smith put much of these earnings back into the entertainment. He commissioned new paintings from Beverley, added musical numbers, and, most substantially, improved upon the lecture hall itself. Taking a cue from the Great Exhibition, Smith conjured an Alpine sense-of-place through a dizzying concentration of goods and crafts from the region. Working off a model commissioned from an accomplished Chamonix woodworker, Smith converted the stage of the Egyptian Hall into the facade of a mountain chalet, featuring shuttered windows, carved banisters, and balconies ornamented with fretwork, all beneath a steep-sloping, straw-thatched roof. Live fish swam among water lilies in a pond that gurgled with fountains, and Edelweiss hung from the rafters. Chamois skins, alpenstocks, heraldic banners, knapsacks, and woven baskets festooned the walls. For the third season, Smith brought over a pack of St. Bernard dogs to be paraded through the audience during intermission. John MacGregor, who had met Smith just prior to his own ascent of the mountain in 1853, remarked that Smith had left little else to see in Chamonix, apart from Mont Blanc: “All the rest has been transferred to the Egyptian Hall in London.”[13]

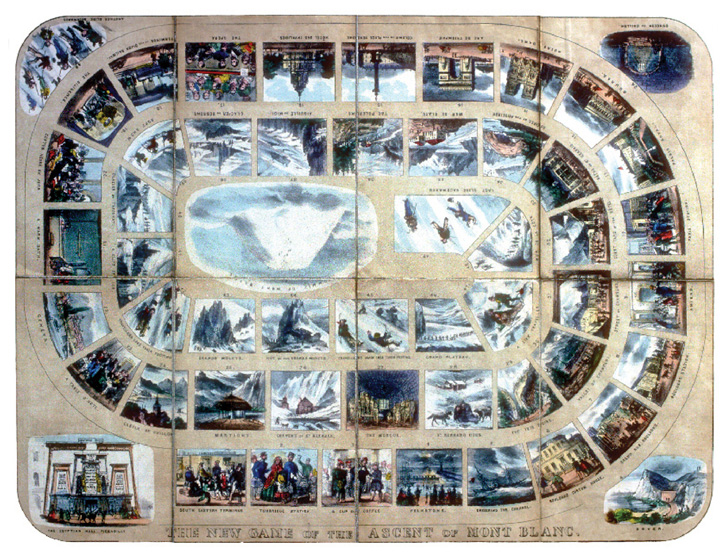

Audiences too had ample opportunity to take home a bit of the mountain. Smith proved an able purveyor of merchandise, producing sheet music for “The Mont Blanc Quadrille” and “The Chamouni Polka,” decorated fans for the hotter months, and even a board-game version of the ascent. For the exclusive inaugural performance of the 1855–1856 Christmas season, guests received an invitation in the form of a passport issued by an illustriously titled Smith, the “Baron Galignani of Piccadilly” and “Member of the Society for the Confusion of Useless Knowledge.”[14] Collected at the entrance to the Egyptian Hall by a ticket-taker dressed as a French gendarme, these passports played up Ascent’s abiding conceit: that patrons were in fact crossing a threshold into an annexed territory of Chamonix, presided over by “His Majesty the Monarch of Mountains.”

Smith’s gesture toward eliminating the distance between Piccadilly and Mont Blanc dramatizes the nineteenth century’s signal technological transformation: the large-scale expansion of Europe’s railroad system. For the price of a seat, Smith brought his audience from stop to stop along a preordained route, simulating the tourist’s itinerary to Chamonix—though not without consequences. As Wolfgang Schivelbusch notes, the railroad’s mechanized transport is a significant corollary to Walter Benjamin’s 1936 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Just as mechanical reproduction diminished a work of art’s “aura”—defined by Benjamin as “its unique existence at the place where it happens to be”—by enabling “the original to meet the beholder halfway,” the proliferation of railroads made possible Smith’s wholesale displacement of Chamonix wares from their original setting, transforming them from local products into theatrical props.[15] The phenomenon of diminishing aura, Schivelbusch argues, may be equally applicable to entire regions, since the railroad brought tourism to areas previously valued for their remote location.[16] About sixty hours away from London by train in the 1850s, Chamonix became host to such a flurry of climbs that in 1856 an exasperated editorial in the Times groused, “Mont Blanc has become a positive nuisance. As the summer months pass over our heads we are pestered with accounts of ascent after ascent, until patience itself is tired out. ... Its majesty is stale, its “diadem of snow” a mere theatrical gimcrack.”[17]

“So many travelers have been going up Mont Blanc lately, both in fiction and in fact,” observes Dickens. On the top of a mountain there is always some fog between the two. Perhaps it is no coincidence that the markers of traditional plot structure—rising action, climax, denouement—accord to the slope of a mountain, for making a climb means constructing a narrative, one that, for his part, Smith could never quite escape. Sitting with Dickens at a dinner of commercial travelers, he is not even halfway through the six-year run of Ascent of Mont Blanc. In total, he will rehearse the climb he made over the course of two days in August 1851 two thousand times, often changing the route, stopping in Amsterdam, or proceeding down the Rhine, but always returning to the same summit. In 1858, he will announce the production’s final performance and set sail to gather material for Mr. Albert Smith’s China, though his “pagoda” theatrical set will bear an uncanny likeness to an Alpine chalet, and in planning the second season Smith will capitulate to audience demand and cap his trip to China with a return to Mont Blanc—even as scores of young gentlemen reenact his climb on the glaciers themselves. Whenever one of these adventurers reaches the top, the citizens of Chamonix play their perfunctory role in the production. As the Times dryly put it: “The bells are set ajingling, the band strikes up, ‘See the conquering heroes, &c.’ A little powder is blazed away and a hot bath and a supper very appropriately wind up the performance.”[18]

Dickens continues with his toast, setting up a favorable comparison between Joseph Paxton’s technical accomplishments and Smith’s showmanship. The pairing is perhaps more apt than Dickens can imagine, for inasmuch as Paxton’s manipulations of glass and steel spur on the train station, the skyscraper, and the shopping mall, Smith’s entertainment—with its screen of moving images, its musical accompaniment, its push towards sensory overload to evoke distant climes—anticipates the all-encompassing environment of cinema. His attempt to recreate the experience of the mountain through the composite parts of narrative, song, alternating vistas, and a multitude of props is a strategy of “multiple fragments which are assembled under a new law”—Benjamin’s description for the filmmaker’s technique of montage.[19] Smith, shifting in his chair, anticipates that he will soon be called upon to perform. Dickens invites him to sing his famous patter-song, “Galignani’s Messenger,” and Smith clears his throat. He rises as an honored guest among travelers, a mountaineer who has walked over glaciers straight into panoramic illustrations, an engineer devising a connecting route between summit and stage, a showman who, at the height of popularity, feels a mountain beneath his feet.

- Charles Dickens, Speeches Literary and Social (London: John Camden Hotten, 1870), p. 117.

- Ibid., p. 123.

- The Illustrated London News, 25 May 1850, p. 366.

- “Mr. Albert Smith’s Entertainment,” The Times, 29 May 1850, p. 5.

- “Mr. Albert Smith’s Overland Mail,” The Illustrated London News, 1 June 1850, p. 390.

- Richard Harris Barham, William Harness, and George Hodder, Personal Reminiscences, ed. Richard Henry Stoddard (New York: Scribner, Armstrong, and Company, 1875), p. 311.

- Albert Smith, “Loose Leaves from the Travellers Album at Chamouni,” Bentley’s Miscellany, vol. x. (London: Richard Bentley, 1841), pp. 579–580.

- Albert Smith, The Story of Mont Blanc (London: David Bogue, 1953), p. 177.

- Ibid, p. 208.

- Ibid, p. 214.

- “Editor’s Easy Chair,” Harper’s, November 1851, p. 851.

- “Mr. Smith’s Ascent of Mont Blanc,” The Illustrated London News, 20 March 1852, p. 243.

- John MacGregor, “An Ascent of Mont Blanc,” The Times, 30 September 1853, p. 6. When MacGregor climbed Mont Blanc in 1853, he met Albert Smith, who happened to be in Chamonix gathering more artifacts for his show. George Baxter’s prints for Smith’s book were based on sketches that MacGregor made during his trip.

- Edmund Yates, His Recollections and Experiences (London: Richard Bentley and Son, 118), pp. 297–298.

- Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Random House 1988), p. 220.

- Wolfgang Schivelbusch, The Railway Journey (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1986), pp. 41–42.

- “Mont Blanc Has Become a Positive Nuisance,” The Times, 6 October 1856, p. 8.

- Ibid.

- Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, p. 234.

Colby Chamberlain is managing editor of Cabinet.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.