Making Sense at the Movies

Habit and memory by the light of the silver screen

Amelie Hastie

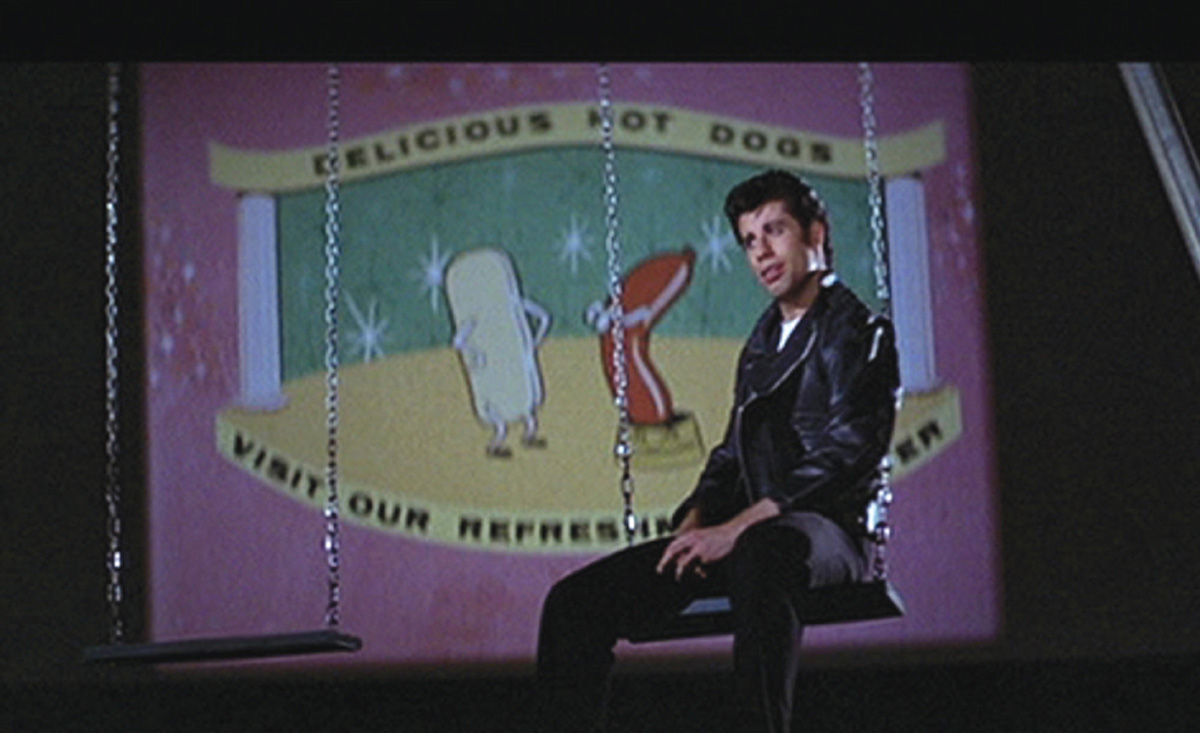

In the early pages of his philosophical musings on eating and its accompanying experiences, Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin maps out the five senses in order to begin to get at the meaning of taste in particular. Our senses together examine different elements of “external objects,” he suggests, but ultimately “taste decides” what these objects are. Moreover, through the state of tasting and eating, he writes, “an unknown languor is felt, objects seem less vivid, the body bends, the eyes are closed, everything disappears, and the senses are in an absolute repose.”[1] Taste—for Brillat-Savarin, the dominant sense—can be frequently overpowering so that at times, in the act of eating, our other senses virtually cease to exist. To close one’s eyes or to gaze on an unfixed object at the moment of eating is surely a sensation everyone has experienced. So why on earth would we want to eat at the movies—a space, it would seem, that is so dependent upon visual and auditory concentration?

The answer is necessarily complicated, dependent upon the context of the experience itself: what we eat, where we eat, and, of course, what we see while we’re eating. Food is alternately complementary and distracting in the movie theater. Like other material aspects of the cinema, food preserves and transforms our experiences at the movies: in a sense, food’s ability to preserve our experience transforms it precisely by thwarting our complete “transportation” into the world of the film. Food might remind us of where we are: in a specific social space, in a foreign city, next to someone we want to touch. Or it might reiterate the ways we experience time at the movies, itself a kind of double-temporality: film’s time is in the present tense and therefore inevitably ephemeral, yet its temporality is also that of recollection. As part of the mise-en-scène at the movies itself, food can invoke both difference and repetition, the continuous present and our unconscious recalling of it. From theater to theater, city to city, our experience is revealed as malleable through the multiple senses engaged in the cinema’s space and time. I encountered and tested these ideas through a tour of four different eating experiences in four different cities—an attempt, therefore, to “research” my senses.

The musty sensation of the Vine immediately reminded me of the theaters in the Times Square of old where I used to go watch secondhand flicks and drink 40s, usually with a couple of bulky male friends flanking me like bodyguards in the dark. This recollection was reinforced when I went upstairs to the bathroom. The door was wide open, the water would not stop running in the sink, and I’m pretty sure there wasn’t any toilet paper. Details upstairs and down together made this one creepy cinema. I hurried downstairs and met my companion at the concessions stand. Pickings were slim—and questionable—and somehow we decided on Milk Duds. We joined the three other patrons (each alone) in the theater. The movie began without any previews.

Kiss Kiss Bang Bang was a favorite film of indie-lovers. But I had very little patience for it, and my companion had even less. To add to our displeasure, when we opened up the Milk Duds, we found that the contents had merged into one large Dud. This did not bespeak the freshness of goods normally available at movie theaters; I wished I had brought in contraband candy that night. I could not possibly eat any of it. After much squirming on either side of the divider, I suggested to my friend that we could leave, and he quickly agreed. “Shall we toss the Dud?” I asked. He confessed that he had eaten the whole thing and showed me the empty package.

This experience of horror at the movies—seedy bathroom, handwritten signs, lack of previews, lack of patrons, crappy food (and a companion who would eat it)—showed me how elements of the moviegoing experience are intimately connected. I am not above suggesting my interest waned in the film because we didn’t have anything good to eat, although the surroundings—both inside and outside the theater space proper—also distracted from the screen. But this distracted viewing mode paradoxically also enhanced the scene in the way it conjured my memories of Times Square in the late 1980s. At the Vine, I moved between these two experiences. In this particular case, their similarity triggered a coalescence that is always potentially present when we go to the movies. Recognizing one experience embedded in the other, I wondered if each film-going experience is in fact a culmination of those that come before it. Do these experiences accumulate into one (like the Milk Duds in our box), or do they occur on a continuous line? Are they, in Henri Bergson’s terms, a form of “habit interpreted by memory” or “memory itself”?[2] “Habit interpreted by memory” is an embodied form of recollection, enabled by repetition of bodily gesture or movement. Such “learned recollection,” Bergson suggests, “passes out of time.”[3] That is, it does not exist in terms of discrete moments we remember separately, but rather takes place in an atemporal state of repetition. “Memory itself,” on the other hand, is represented by a “memory-image” and is enabled by perception rather than repetition. A moment is mentally conjured rather than physically repeated. In the realm of cinematic experience, I see these two forms as inevitably intertwined, so that habitual repetition can lead to an understanding of the differences between the things repeated; this realization, in turn, evokes a memory-image. Going to the movies can become automatic, even “outside of time,” but the slight differences we experience (not just in terms of what we see but where we are and even what we eat) help us to form memories set in time.

Cheap to produce in mass quantity, it can also be eaten in bulk without too much caloric intake (depending on the condiments one chooses) and without much thought, but it is also, as everyone knows, a noisy food that potentially always distracts those around us. For me, the sweetened corn in Shanghai was perfect: I prefer sweet to salty anyway, and the syrup slightly dampened the crunch so that I was less self-conscious of the racket I was making. Most importantly, in this case the rhythm of my eating perfectly matched the affective rhythm of my viewing, for I was seeing an American thriller. Raising and lowering my hand to put piece after piece in my mouth, I ate the popcorn as a response to and a symptom of the anxiety caused by the film: a threat to a family from outside forces.

Taking further license with Bergson, I might say that eating popcorn is a form of “habit interpreted by memory.” Writing several years after Bergson, Sigmund Freud shifts these terms somewhat, though surely they can be productively set alongside one another. Repeating, Freud tells us, is a way of remembering.[5] Though initially it is an indication of repressed material (for Freud, this almost always has to do with childhood trauma and sexual identity), repetition becomes a form of remembering because sometimes it’s the only way to remember. But what might be repressed at the movies, replacing the Bergsonian instance of “memory itself”? The repetitive eating of popcorn at a thriller is, to be sure, a management of anxiety—in this case, part of an anxiety caused by a thriller. But the habit of this repetition is also functioning as a different sort of memory. As bodily “habit,” in Bergson’s terms, it provides a sense of continuity between different films, different spaces. This gesture might give us the impression of being nowhere (and maybe being “timeless”) at the movies, in the dark, so that it potentially represses the fact that we are somewhere. Yet, even while the repeated act of eating it allowed me to “remember” I was in a familiar space—“at the movies”—the taste of Shanghainese popcorn ultimately functioned as a reminder that I was in a national space new to me. Functioning as a kind of contingency factor, the popcorn burst the sense of nowhereness and timelessness that cinematic memory-formed-by-habit seeks to produce. The sense of taste therefore evoked a perception of where I was—a space that is timeless and placeless but also nationally and temporally specific. In effect, my experience was destined now to become “memory itself.”

It was the third week in May, smack in the middle of Cannes. This made the offerings in Paris fairly meagre—primarily films that seemingly couldn’t make it into the festival. This point was made evident by the ads that preceded the screening, which included ones for the festival itself as well as for movies being screened there: Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette and Pedro Almodovar’s Volver. As it turned out, Quatres Etoiles took place in Cannes, but it seemed to me that was the closest it could get to the festival. Cherries, cookies, and a crummy French film I could only half-understand (my language skills being still trapped, embarrassingly, in second-year college and graduate translation courses) conspired against me. A mild interest in the plotline and an attempt to test my comprehension partly kept me watching, but my fascination with the cherries, the cookies, and the space of my viewing in this cinema and in this city commanded most of my attention. The cherries took me back to Rue Mouffetard, back to other potential theaters and missed films, back to the moment in California when I later saw the street in the film with the central character whose name I shared (and woke up the friend beside me to share my recognition not of my own name but of the street I’d visited months before). I wished I were in another theater, or at least with another film. Exhausted by these desires, eventually I shut down my senses and fell asleep.

I would like to say that this brief snooze led to a reverie about cinema—perhaps about Paris after the war, when publicly watching American films, banned in the years of Nazi occupation, was a political act—but in fact it was just a moment of sensory overload coupled with a sense of boredom. The following afternoon, a rainy Saturday, I consciously sought just such a waking reverie, when my companion and I went to a small repertory cinema that was playing a new print of Mildred Pierce to a seemingly sold-out crowd and Magnificent Ambersons to the rest of us. Bathrooms were attached to each theater (rather than the lobby), and no concessions were sold; these details suggested to me that we were not to be distracted from the film (at least not for long) by any other corporeal pleasures or requirements. Even though, or perhaps because, Paris is a center not only of cinephilia but also of haute cuisine, intellectual art-house cinema is not normally complemented by junk food (or, really, eating of any sort). Turning to Paris in the twenty-first century, I was acknowledging it as the space of origin of a particular kind of post-war cinephilia sixty years prior that also led to the study of cinema as an object worthy of analysis, as in the journal Cahiers du Cinema. At L’Action Christine I entered this space of history—or of feigned recollection—in which popular French film was abandoned in favor of Hollywood and B-movie productions. It was, in fact, my own pattern of viewing in the previous two days.

But of course I was here on a different sort of mission—perhaps inside and outside of the history that haunted this theater. After all, the post-war Cahiers writers who originally defined film “auteurs” never wrote about what they ate—just the images they loved. And so I wondered: is my travel from Shanghai to Paris a kind of nostalgia for cinephilia itself, moving from the place of contemporary “new waves” to those past? Is it a means of taking seriously that other thing I love at the movies, the treats I eat alongside them?

The concessions stand out front sells typical fare such as popcorn and sweets, as well as what’s become the standard offerings at other theater-pubs: pizza and beer (ten different microbrews), as well as salads and hotdogs. Dylan and I each chose a slice along with a glass of beer. Perhaps most exciting were the trays which held the goods: complete with a cup holder that in turn fit into the cup holder on the armrests in the theater. This way the trays could be set on the viewer’s lap without even the distraction a box of popcorn in our hands might produce. As we sat with our goods, Dylan’s friends filed in; two sat in front of us but then swiveled their bodies in their seats to face us instead of the screen (at least before the movie began to play). Food in laps, beer in hands, eyes partly on me, the theater became a social space before us.

The theater-pub is an acknowledgment of what takes place at the movies. Designated as a space in which we eat and watch, it would seem to be the ultimate form of a movie house. However, this explicit admission that movie viewers have become trained to eat while watching alters rather than defines the fundamentals of the experience. Eating a meal is certainly different than repetitive nibbling; hardly a force of habit at the movies (unlike at the television screen, perhaps), it distracts the senses rather than engages them simultaneously. The film, in effect, becomes an accompaniment to eating rather than the other way around. Multiple senses are indeed engaged but, as Brillat-Savarin suggests, they also, momentarily, “disappear.” Rather than time not passing—as happens in the act of habitual recollection—questions of cinematic time are altogether irrelevant, as we lose sight even of the movie itself with each sentient bite of pizza or sip of beer. The very novelty of this food takes me out of the visual space of the film, almost out of the cinematic space itself, and it also illuminates the social nature of the space we’re in.

Of course, repeated trips to theater-pubs might change all that as well. And for now, the Red Vines (sweet red licorice, packed in strips in white boxes wrapped in blue cellophane) do the trick. My favorite sweets at the movies—often smuggled in since they are a third of the cost at the drugstore than they are at the theater—they return me to the force of habit: my hand reaches into the box, grabs a strip, raises it to my mouth, and I bite. My chewing might distract me ever so slightly as I view, but this familiar, even routinized practice lodges me at the cinema.

- Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, The Physiology of Taste: Meditations on Transcendental Gastronomy (New York: Liveright, 1970), p. 9.

- Henri Bergson, Matter and Memory (New York: Zone Books, 1990), p. 85.

- Ibid., p. 83.

- James Lyons, “What about the Popcorn? Food and the Film-Watching Experience,” in Anne L. Bower, ed., Reel Food: Essays on Food and Film (New York & London: Routledge, 2004), pp. 311–333.

- Sigmund Freud, “Remembering, Repeating, and Working Through,” in Beyond the Pleasure Principle and Other Writings (London: Penguin Books, 2003), p. 36.

Amelie Hastie teaches at the University of California-Santa Cruz. She is the author of Cupboards of Curiosity: Women, Recollection, and Film History (Duke University Press, 2007) and has recently edited an issue of Journal of Visual Culture on “Detritus and the Moving Image.”

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.