Utopia on the Roof of the World

The search for Shambhala

Chris Wiley

Somewhere high up in the Himalayas, surrounded by a range of snow-capped peaks treacherous enough to defeat even the most intrepid mountaineer, lies a kingdom of unparalleled splendor, peace, and tranquility. This place, known as Shambhala, is home to palaces built of rare stone and pure gold and bedecked with a lapidary’s laundry list of precious gems, glasses, and colored corals. There are lakes where Shambhala’s noble, healthy, and prosperous subjects cavort in boats carved from jewels, and a lush sandalwood grove where they can peacefully contemplate an enormous, three-dimensional Mandala of unparalleled opulence. But beyond this bountiful earthly splendor, Shambhala is also a privileged spiritual realm—those who are born there are guaranteed to achieve Enlightenment in the span of a single lifetime. It is, in short, a paradise—a utopia cordoned off from the world not by water, like Sir Thomas More’s famous island, but by tectonic eruptions of stone.

It is also, of course, a myth, though one that has been, and continues to be, taken as serious, geographic fact by both Eastern and Western Buddhists, as well as a cavalcade of mystics, occultists, ufologists, New Agers, and Neo-Nazis. This credulous attitude towards the Shambhala myth may seem absurd, but it has furnished history with some of the oddest stories of the West’s fantasies about, and interactions with, the Far East.

The Shambhala myth is derived from a number of esoteric Buddhist texts, primarily the Kalachakra Tantra. Taken together, these texts provide detailed descriptions of the kingdom, trace the arc of its history, and prophesy its future. We are told that the enormous, lotus-shaped, mountain kingdom is ruled by a lineage of wise, august monarchs, who each reign for a hundred years. They serve as the keepers of the sacred Kalachakra teachings, which were passed down by the Buddha to Shambhala’s first king, King Suchandra. By living according to these esoteric teachings, all of Shambhala’s millions of villagers have fulfilling, enlightened lives. Despite the relative humbleness of their villages when compared to the extravagances of the capital city, they are left wanting for nothing.

While the Kalachakra Tantra describes Shambhala as a perpetual bastion of peace and wisdom, it also foretells the decline of the world beyond its borders, where the Buddha’s teachings will gradually be forgotten. The climax of the kingdom’s history arrives when the outside world has reached its spiritual nadir: then, Shambhala’s last king, Rudra Chakrin, and the kingdom’s vast armies will mount their horses and gallop over the mountains, cleansing the world of blight and ushering in a thousand-year Golden Age.

It is an evocative eschatology, a fantastic ending to a fantastic tale. It is not surprising, then, that during the heyday of Western imperialism, as the Orientalist-minded began to mine the exotic religious traditions of the Far East for new sources of spiritual expression, Shambhala should make its way into the vocabularies of such seekers. But, of course, the Shambhala myth did not just appear, ex nihilo, in the drawing rooms of the West’s occultist elite. Instead, it was placed there—almost single-handedly—by Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, the eccentric matriarch of the Theosophical Society.

Madame Blavatsky, or HPB, as she was commonly referred to, was a self-described “hippopotamus of an old woman” who, despite frequent accusations of charlatanism and allegations made by the British government of spying for the Russians, managed to establish a worldwide network of devotees to her particular brand of esotericism. A spiritual vocation of Byzantine complexity, Theosophy may be understood as a unique bricolage of spiritualism, ancient mythology, Eastern religion, and the legendarily turgid mystical novels of Edward Bulwer-Lytton. The Shambhala myth made its way into Blavatsky’s mystical stew through an account of anthropogenesis offered in her most famous book, The Secret Doctrine (1888).

Put briefly, The Secret Doctrine retells human evolution as a progression of five distinct “Root Races.” Each of the historical Root Races (with the exception of the first, which had no physical form) inhabited a different mythological continent: the second inhabited Hyperborea; the third, Lemuria; the fourth, Atlantis. According to HPB’s account, Shambhala became the place where surviving Atlanteans fled after their homeland sank into the ocean. From there, the Atlanteans shared their culture and wisdom with a fifth, overlapping Root Race, which has since spread out across most of the known world: the Aryans.

Theosophy’s fantastical tales turned Shambhala into fodder for those already hungry for the occult. But some were not content to let the stories of this mythical land simply rattle about in their parlors. With its intoxicating blend of utopianism, exotic religion, and potential adventure in far-flung lands, the Shambhala myth proved too compelling to let lie.

Considering the importance of Blavatsky’s phylogeny for those interested in Aryans and Aryanism, it should come as no surprise that some of those stirred to action by the Shambhala myth were members of the Nazi party—in particular, those working under Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler in a branch of the SS called the Ahnenerbe, which served as the organization’s “Ancestral Heritage” office. The Ahnenerbe was Himmler’s pet project, established to trace the heritage of the “master race” back to its origins. It was to this end that, in 1938, five SS officers were sent on an expedition to Tibet.

The Ahnenerbe’s “scientific” endeavors were colored by Himmler’s library of bizarre beliefs, which ranged from the pseudoscientific (he was an advocate of Hans Hörbiger’s World Ice Theory, which posited that the universe is shaped by the continual battle between fire and ice), to the merely egomaniacal (he was convinced that he was the reincarnation of the tenth-century Saxon king Henry the Fowler, and organized expeditions to prove this). As a result, the Ahnenerbe was staffed by an assortment of cranks, amateurs, and, in the case of Karl Maria Wiligut, often referred to as “Himmler’s Rasputin,” the clinically insane. This made for a combustible mix of occult belief and all manner of contemporary pseudoscience. And so it was that the Shambhala myth, filtered through Theosophy, came to meet phrenology and physiognomy on the Tibetan plateau.

The main players in the SS expedition were Ernst Schäfer, a famous explorer and zoologist who served as the expedition’s leader, and Bruno Berger, who served as the team’s anthropologist. Unlike many in the Ahnenerbe, Schäfer was a respected scientist, and it remains unclear whether his allegiance to the SS was ideological or, as he later claimed, merely opportunistic. Berger’s alliances were slightly more clear-cut. During his time on the “Roof of the World,” he measured the heads of Tibetans with menacing calipers that pinched and prodded, and made physiognomic facial casts out of torturously slow-drying plaster, all in hopes of finding traces of the master race. Berger would later be involved in gathering anatomical specimens from among the prisoners in Auschwitz, in preparation for a never-realized expedition to the Caucasus with Schäfer’s then-newly established Sven Hedin Institute for Inner Asian Research.

When the members of the Ahnenerbe’s “German Tibet Expedition” returned in 1939, laden with animal skins, artifacts, holy texts, photographs and film reels, and, of course, the facial casts and phrenological data collected by Berger, Himmler declared the expedition an unqualified success. Though in this case Shambhala served as merely a catalyst for the journey rather than its destination, the “German Tibet Expedition” sparked later assertions—despite lack of evidence—that the Nazis made frequent, secretive trips to Tibet in search of the utopian kingdom itself. These rumors have made Shambhala central to a branch of contemporary Neo-Nazi thought known as “Esoteric Hitlerism.” Miguel Serrano, a former Chilean diplomat and major figure in the Esoteric Hitlerist movement, in fact asserts that Hitler did not die in Berlin but rather fled to Shambhala (in Serrano’s account, relocated from the Tibetan Himalayas to the center of the earth), whence he will soon emerge, astride a white steed and flanked by an army of UFOs, to inaugurate the “Fourth Reich.”

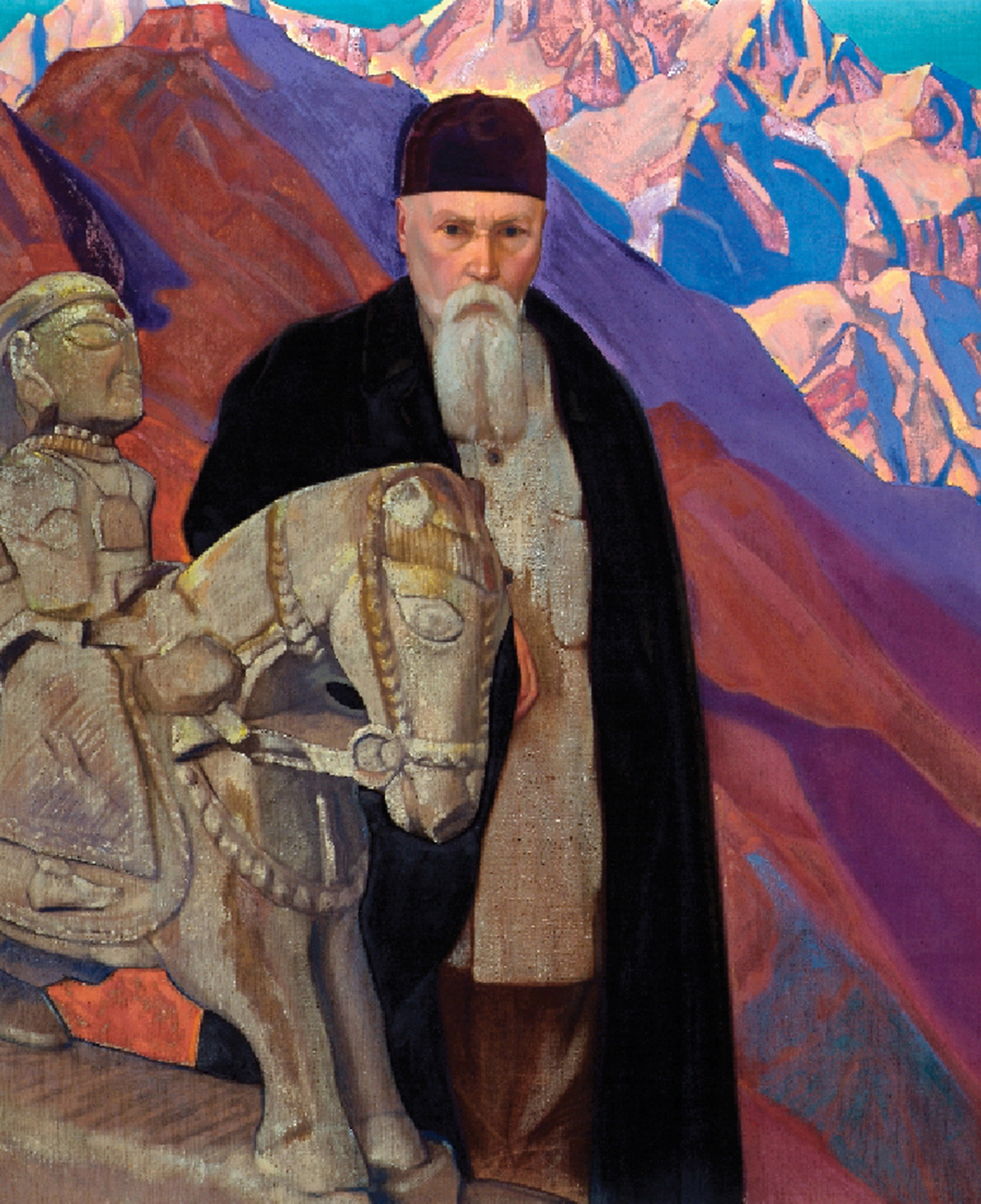

Despite scant evidence that the Nazis journeyed to Tibet in search of Shambhala itself, the “German Tibet Expedition” was preceded by two Tibetan expeditions led by a man who most certainly was: Nicholas Roerich, once a world-famous painter and renowned mystic who lent his name to a major international treaty, was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize three times, and played a behind-the-scenes role in the Roosevelt administration. Roerich rose to fame at the beginning of the twentieth century in his native Russia where, in addition to his painting practice, he designed sets and costumes for the theater, most notably for the Ballets Russes’s staging of Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps. He was also involved in Moscow’s flourishing occult movement, which orbited around HPB’s Theosophical teachings. It was through his involvement in the construction of a Theosophical-Buddhist Temple in Moscow in 1909 that he met Agvan Dorjiev, a major player in Russian-Tibetan relations and tutor to the thirteenth Dalai Lama. Dorjiev’s fascination with the location of Shambhala would inspire Roerich’s epic quest.

By the time Roerich moved to New York City in 1920, he had developed a complex system of beliefs surrounding Shambhala, which he concluded was located in the Himalayas. For Roerich, Shambhala was linked not only to the myth of the Holy Grail but literally connected to the Altay Mountains in Central Asia via a series of underground tunnels that joined it to Belovod’e, the “Land of White Waters” from Siberian mythology. However, Roerich’s most outlandish belief, which he hid from all but his closest confidants, was that he and his family were fated to play an integral role in bringing about the dawn of the Golden Age.

Roerich referred to his project of bringing about the eschatological prophecies laid down in the Kalachakra Tantra as the “Great Plan.” He believed that it was his calling to found a pan-Buddhist state, which would unite areas of Russia, Mongolia, and China with Tibet, and whose creation would finally summon the armies of Shambhala from their mountain stronghold. For most, a plan this grandiose would flounder in the realm of delusion. But Nicholas Roerich had powerful and influential friends and two of them—Louis L. Horch, a successful Wall Street currency broker, and Henry A. Wallace, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s secretary of agriculture and, later, his vice president—would respectively fund Roerich’s two lengthy expeditions in the Far East. The exact details of what occurred on these expeditions remain somewhat cloudy, as Roerich, ever secretive about his geopolitical scheming, preferred to maintain in public the persona of an artist, scholar, and guru. However, his actions were public enough to garner the attention of at least a half-dozen governments that were convinced that he was a covert political operative.

Despite his best efforts, Roerich’s pursuit of his “Great Plan” finally ended in scandal and disappointment. His fall from grace was precipitated by his actions during his second journey east from 1934 to 1936, which was funded—with taxpayer dollars—by Wallace’s Department of Agriculture. While Roerich’s first expedition had, on the surface, been an artistic and scholarly one free from political significance, this second expedition was organized to gather drought-resistant grasses that would help combat the American Dust Bowl. Like Horch, Wallace was aware of Roerich’s ulterior motives—or at least some of them—as the two had maintained, in the years preceding the expedition, an extensive, mystically-oriented correspondence in which Wallace played the part of Roerich’s awed and obedient pupil. However, Wallace could not have predicted that Roerich would allow these secret motives to take total precedence over the serious mission with which he had been entrusted, and leave the exasperated botanists who had been put in his charge to chase him across Japan, China, and Mongolia.

Though it would take some time for Wallace to see Roerich as anything but infallible, the utter lack of botanical specimens returned for the purpose of erosion control (Roerich did send back a number of superfluous medicinal herbs) left Wallace increasingly disillusioned with his former guru. Roerich’s funding was suspended in 1935, and his expedition’s misadventures opened the way for Treasury Department allegations of tax evasion, as well as a lawsuit filed over old loans by a similarly disenchanted Horch, who had, in addition to the money he fronted for Roerich’s first expedition, funded the creation of the Roerich Museum in a palatial building on New York’s Upper West Side. After the calamitous end to his final Tibetan excursion, Roerich settled permanently with his family in India’s Kullu Valley and never returned to the United States. Though he and his family remained prominent figures in India, counting among their friends the future Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, Roerich’s fame in the West faded. Even the Roerich Museum, once ensconced in Horch’s imposing, twenty-seven-story Art Deco skyscraper, was relegated to a modest townhouse on a sleepy side street, where it remains today.

Similarly, the Shambhala myth itself has gradually slipped from its prominent place in the Western imagination. It now resides only in a few scattered outposts, maintained by groups with eclectic subcultural proclivities. It has, however, persisted as a vestigial cultural memory, sneaking into the popular lexicon in disguise. When the West dreams of a utopian mountain hideaway, it now dreams of Shangri-La. The name itself is enough to conjure visions of clear mountain streams, and lush, sequestered valleys in exotic locales. However, it is not a name that has its roots in some occluded, mythic past, as one might be led to suspect. Instead, Shangri-La arrived in our collective fantasy life through Lost Horizon, a 1933 novel by James Hilton, in which Shangri-La is the name of a utopian lamasery in the Tibetan Himalayas that seems to exist outside of time. Hilton’s Shangri-La is clearly based on the Shambhala myth, though he has Westernized some of its aspects (rather than acting as a storehouse for esoteric spiritual teachings, for instance, Shangri-La is fashioned as a modern-day Library of Alexandria, which will keep the world’s cultural treasures safe during the coming apocalypse), and it is this version that has seeped into our contemporary fantasies of the place. Thus Shambhala remains with us in a third-generation form—no longer the impetus for daring or dastardly exploration of far-flung lands, it has moved from myth, to fiction, to a mere passing daydream.

Chris Wiley, a former editorial assistant at Cabinet, is a Brooklyn-based photographer and writer. He recently received his MA in Contemporary Art Theory from Goldsmiths College, London, and is working as a researcher for Charley 05.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.