Colors / Ash

An emphasis on repose

Meghan Dailey

“Colors” is a column in which a writer responds to a specific color assigned by the editors of Cabinet.

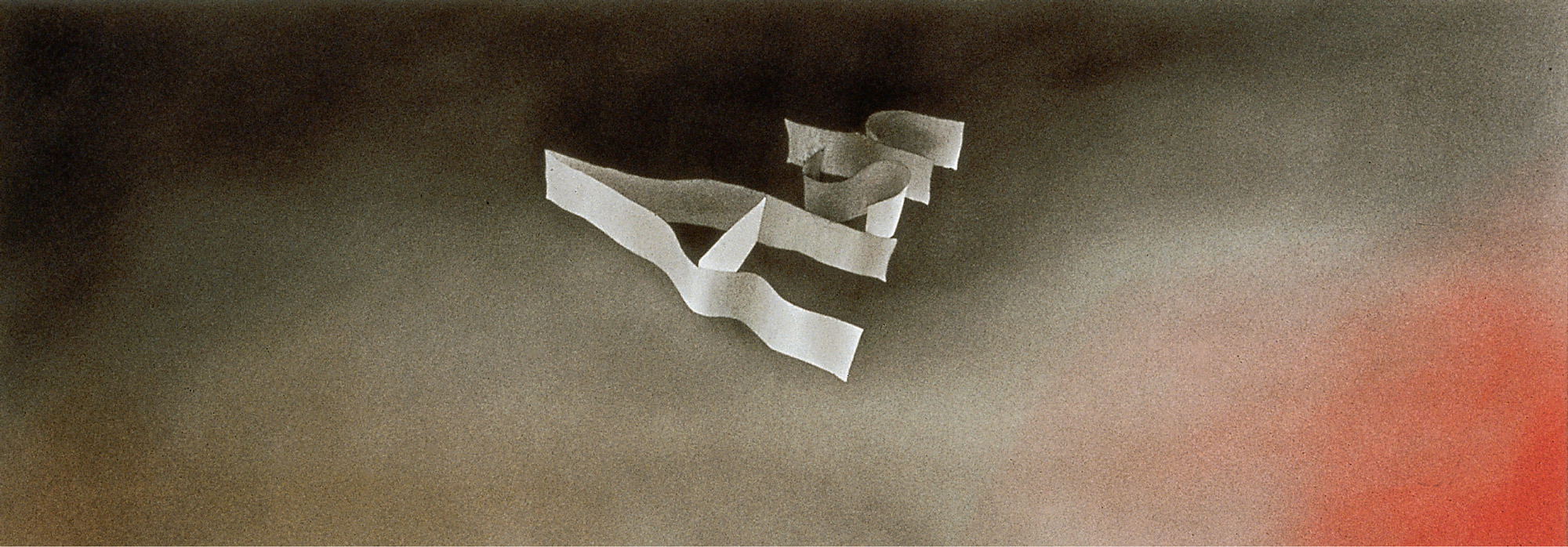

The identity of ash as a color is questionable. Ash is not ashen—drained of color—but variously gray, whitish, black-like, flecked, dirty, streaked. It can be steely and cold, or the harsh, smoky yield of raging flames. Intangible, abstract, but also very much there, even if only in trace form, ash is an absolute result. Elsewhere, ash is a mood. It speaks of melancholy, New England maybe—turning leaves on ash trees under overcast skies in damp autumn air, that sort of thing. Ed Ruscha’s drawing Ash (1971), rendered in gunpowder and pastel, perfectly crystallizes its valences and free–floating (literally) signification. For Ruscha, words are ever the stuff of extended reflection, of puns and hidden meanings, presented as plain as day. I like to think that he must have enjoyed the particular convergence between word and medium (a combustible substance in its pre-asheous state).

One can experience ash by wearing it. The LL Bean catalog sells “Bean’s Sloggs,” an outdoor shoe available in color ash as well as color black, and also some men’s casual trousers in ash—just one among many barely distinguishable neutrals the company offers: taupe, beige, moss, peat, stone, timber, fatigue. The clothing and colors signify the outdoors, and are situated and named as part of nature’s continuum. But peat and stone are going to outlive the whims of consumer taste. Ash’s relevance as something wearable is proven on Ash Wednesday when, out of humility and sacrifice, Catholics receive ashes on their foreheads as a sign of penitence. Before Mass, many blessings are bestowed upon the incinerated palm branches, then the priest smudges a little sign of the cross on your forehead and reminds you of your future state as dust. In early Christian times the faithful, in their hair shirts, would toil and seek penance and sacramental absolution for forty days. The contemporary equivalent? I contemplate wearing my ashes to an afternoon press preview at a New York museum. How long will I last before wiping them off? (Practically a sin.) St. Anthony’s church on Houston and Sullivan has a Mass every half-hour. Stop by, repent, get your ashes.

In France, ash is a verb. To envision life there (I’m thinking of Paris, specifically) as one comprised of a remarkable number of hours spent smoking and sitting or waiting or reading, but always smoking, is to conjure more than mere cliché. They love their cigarettes. There’s a tearoom in Paris, in the fifth arrondissement, in the Mosque de Paris. People arrive there early with nothing but a pack of Gauloises Blondes and a copy of that day’s Libération. Some remain there for leisurely stretches of time—the kind of open and unencumbered time that most people only jealously dream of possessing. But regardless of the circumstances under which they are smoked, cigarettes are ubiquitous, and Parisian hands seem never to be without one. Consider the sheer amount of ash produced (once all the butts have been sifted away) by the act of smoking down and flicking (only occasionally, however, for maximum ash length) all of those ciggies. One imagines a gently shifting range of ash dunes, soft as talc, on the outskirts of Paris, in the banlieue, or out on the suburban banks of the Seine, temporarily eroded by rain, but built up again by the endless supply of carbon cargo brought in by the fleet of Renault dump trucks that offer round-the-clock transport of the residue of that toxic, intoxicating daily habit.

Such imagery is doubtless a product of this non-smoker’s perverse fascination with a smoke-loving culture. It’s bigger, though. For me, ash has become a metaphor for the Parisian emphasis on repose. It has been transformed into something I call ashitude. In France, simple inquiries such as “Did you receive my letter?”, “Do you know when Mlle. Blanche will return?”, “Is it possible to purchase this item?” and so on, seem so often to elicit a “non.” Ashitude is a particular form of dismissal; don’t look for sympathy, expect shrugs. Example: If you leave your Filofax on a payphone at Orly Airport, don’t count on getting it back. Go ahead, call the bureau des objets trouvés, maybe they’ll be open. Maybe they will answer the phone. If they do, inquire in faltering French whether anyone has found un agenda in the terminal. Silence. Then a casual yet considered response: “Un agenda… non, non….” The shame and disbelief that the contents of your life are now possibly amongst cheese rinds and Café Kimbo grounds (and, yes, cigarette butts) in a French landfill, and the utter disregard with which your plea is met, prompt the following scene to flash across your brain: The gentleman on the other end of the phone is sitting, smoking the most aggressive cigarette ever rolled, thumbing through your Filofax and ashing on its pages. Non, non, non. Ash, ash, ash. You thank him anyway, wish him a very bon jour, and hang up, understanding that your concept of time has been refreshingly, maddeningly done away with. It is now as lost as the precious Filofax, which might as well be a pile of ash for how its log of days, activities, encounters, and numbers now exists only as a trace in your mind. This unknown French ash–man, having successfully killed time—just simply extinguished it like his last cigarette—has demonstrated something of how incidental language is. In the translation from one to the other, the particularities and references of your respective languages—more broadly, your sensibilities—were lost. Maybe a few cigarettes were not the only casualties of your exchange.

Meghan Dailey is an editor, writer, and art historian in New York and contributes frequently to Artforum and Time Out New York. Her first curatorial effort, “The Approximative,” opened in May at Galerie Ghislaine Hussenot, Paris.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.