The Celestographs of August Strindberg

Collaborating with the weather

Douglas Feuk

Few outside of Sweden know that the playwright August Strindberg had periods of intense engagement with painting and photography in the 1890s, when his literary creativity had reached a deadlock. In an essay from 1894 called “Chance in Artistic Creation,” he describes the methods that he employs, speaking about his wish to “imitate […] nature’s way of creating.”[1] This text is strangely prophetic, foreboding the automatic techniques of the twentieth century. His method is to start more or less at random, trusting nature’s inherent desire for form (what he calls “matter’s drive towards representation”) to eventually make the picture develop out of the paint, almost by itself.

In his paintings there is always a “motif”—often stormy skies, agitated waves, perhaps a lonely rock by the sea. But these landscapes or seascapes are still half-embedded in the material, like a world in the process of being created. Boundaries and differences are fluid: Air might have the same density as stone, and the rock seems mysteriously fused with the water—as if they were all but different manifestations of the same matter. In fact, the tactile surface in Strindberg’s paintings is at times emphasized so much that not only does it provide an image of nature, it also, in part, gives the impression of being nature. In the painting High Sea, for example, there are sections that Strindberg has blackened with a burner, but also patches of a brownish-gray, rough structure that seem to be not so much painted as oxidized, or in other ways created by some elementary process of nature.

Convinced that he had changed the development of painting in a progressive direction, Strindberg published his essay on chance and artistic production in a Parisian journal. And in his experimental photography from the same year, there are examples of images that are even more in line with what he called “natural art.” I am thinking of his “celestographs,” where the surfaces not only look weathered with an atmospherically-created patina, but even seem to have been made in physical collaboration with the weather.

Strindberg distrusted camera lenses, since he considered them to give a distorted representation of reality. Over the years he built several simple lens-less cameras made from cigar boxes or similar containers with a cardboard front in which he had used a needle to prick a minute hole. But the celestographs were produced by an even more direct method using neither lens nor camera. The experiments involved quite simply placing his photographic plates on a window sill or perhaps directly on the ground (sometimes, he tells us, already lying in the developing bath) and letting them be exposed to the starry sky.

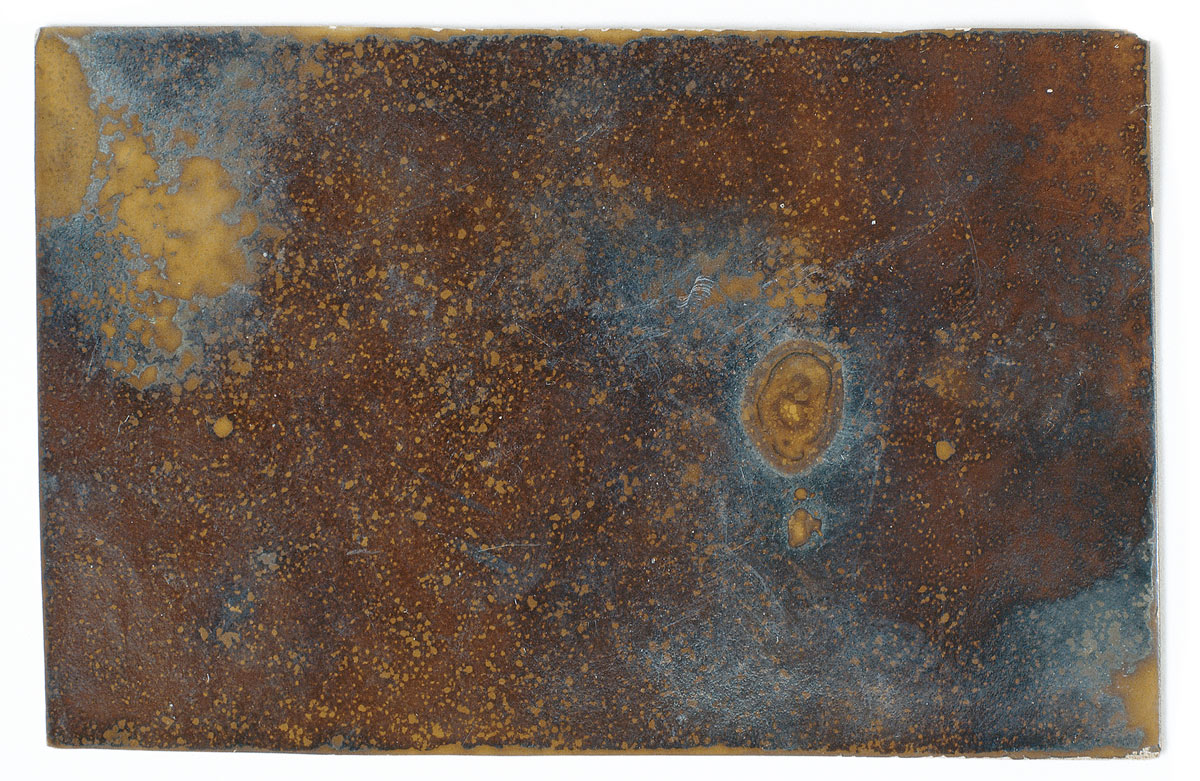

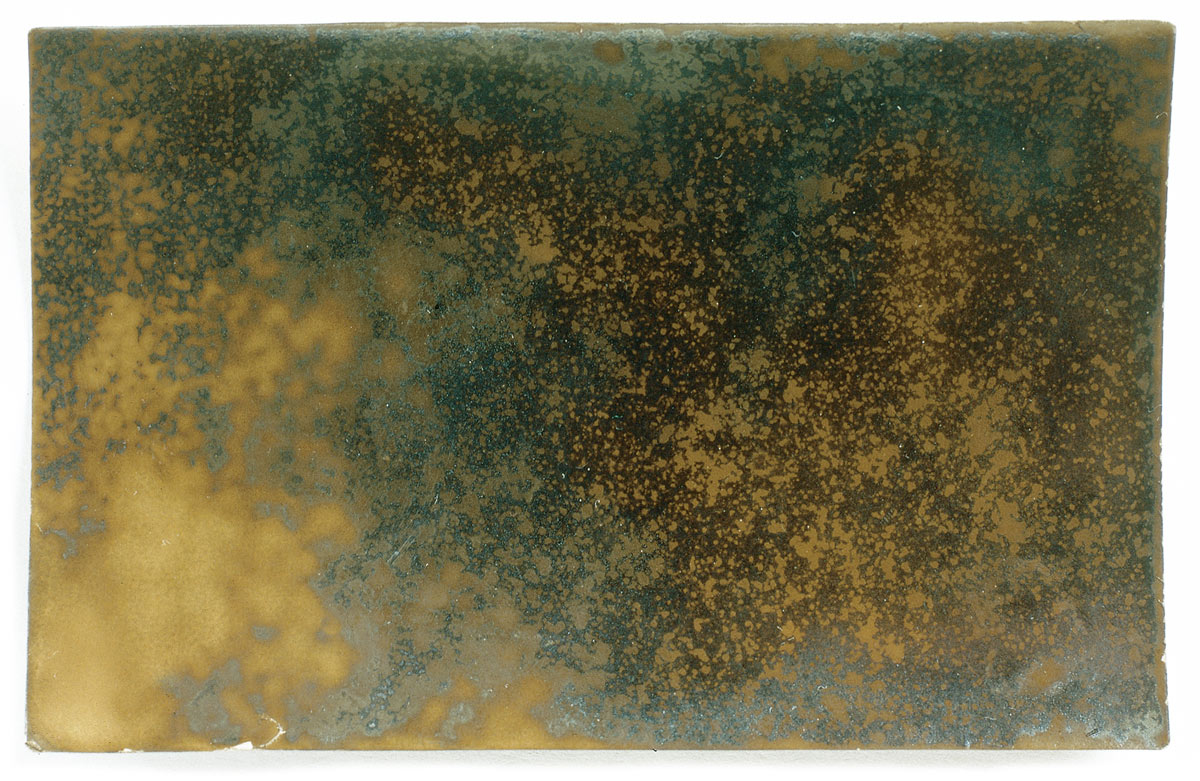

The black or darkly earth-colored pictures that eventually appeared are strewn with a myriad small, lighter dots that Strindberg thought were stars. That they might have been drops of dew, some kind of atmospheric particles, or just some dirt in the developer cannot be ruled out. As soon as the experiments were finished, Strindberg sent both photographs and a written account to the famous astronomer, Camille Flammarion, in Paris. But despite his own mystical inclinations, Flammarion must have considered this photographic method all too absurd and Strindberg never received the official recognition for which he was yearning. Indeed, as a contribution to science or as a representation of nature, these pictures are of course worthless. Their imaginary value, however, is an entirely different question.

Certainly, the photographs often look like nocturnal celestial scenes. But you could just as easily see gravel or dust, a close-ups of worn asphalt, or a patch of dark soil. Actually, the pictures are not totally unlike the topographical earth studies that much later, in the 1950s, engaged Jean Dubuffet, which he named texturologies. The greatness of Strindberg’s photographs lies precisely in that they offer this double view, where starry sky and earthly matter seem to move within and through one another.

Today, science believes that this is actually so. All elements heavier than hydrogen and helium are created in nuclear reactions inside stars and then thrown out into space, especially in the gigantic eruptions of supernovas. Almost every atom that makes up our material world of stones, plants, and human beings must once have been inside of exploding giant stars. This would mean, in a dizzyingly material sense, that we are actually made out of stardust. But more symbolically, the celestographs also seem to meditate on the links between the dark earth and the celestial light and life force. I understand them as a reverie on correspondences between micro- and macrocosmos—or between light and dark, high and low, gold and dirt.

This sounds like very traditional idealistic symbolism. But what is remarkable, and what makes these images so “modern,” is that they also concrete examples of a kind of chemical naturalism (as in the work of Polke, Kiefer, and many other recent artists). Strindberg insisted that art should try to “imitate […] nature’s way of creating,” and in these celestographs the image and the world have approached each other to the extent that they more or less merge. Whatever the coincidences were that created these pictures, the subject matter appears less as a photographic image than as a “work” by nature itself.

The transforming processes of nature have continued to develop the photographs during the century that has passed since they were made. Thumbprints have left traces, and grease or ink stains on the back have in time wandered through the paper. Strangely enough, this has not ruined, but rather perfected these images of night—sometimes with light veils of bluish precipitates, sometimes with rusty brown oxidized spots that could possibly be interstellar dust clouds or just ordinary earthly skies lit up from below.

It is highly likely that these “clouds” or this “circular nebula” are details that Strindberg himself never saw, and that they only appeared much later. But it is just as likely that this was a metamorphosis that would have been to his taste. After the mid-1890s he increasingly believed that nature is of a spiritual character and, in line with much of the Romantic nature philosophy of the time, he claimed that nature tended to manifest itself to man in signs and symbols that are difficult to interpret. During the last years of his life he was very preoccupied with clouds, and during 1907 and 1908 he often noticed cloud formations that returned in the same shapes and to the same places around Stockholm. In an attempt to understand what they could “mean,” he photographed and made a lot of drawings of these cloud banks, and he also described the phenomenon in A Blue Book.

Goethe and Constable were early practitioners of an analytic, quasi-scientific study of clouds, and studying clouds was of enormous interest for many other nineteenth-century landscape painters. But Strindberg is not an open air painter. He reads the clouds less meteorologically than metaphorically. What they have to say about air pressure and weather changes interests him less than the fact that they sometimes look like mountains or a pile of boulders. It happens more than once in his paintings that the motif oscillates between images of clouds and images of the “Alps.”

Earth and sky communicate with one another. “Everything is created in analogies, the inferior with the superior,” writes Strindberg. And for Strindberg as draftsman and painter and experimental photographer, the true subject is primarily these “correspondences” that the pictures seem to reveal. Even clouds that he draws become in some sense a celestograph; a kind of “heavenly script,” and yet another example of what he saw as nature’s artistic striving for form: an inherent cipher, hard to understand but still hopeful, like a glimpse of a great other, “boundless” totality.

Translated by Birgitta Danielsson

An English translation of Strindberg’s essay “Chance in Artistic Creation”

- Strindberg’s text was written in French and printed in the Paris journal Revue des Revues under the title “Du hasard dans la production artistique.” It is available in English in Douglas Feuk, August Strindberg: Inferno Painting and Pictures of Paradise (Copenhagen: Edition Bløndal, 1991).

Douglas Feuk is an art critic and a freelance curator living in Stockholm. His books on Swedish artists include August Strindberg: Inferno Paintings and Pictures of Paradise (Copenhagen: Edition Bløndal, 1991).

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.