Behind the Shield

How the sheriff got his star

Jon Calame

In the autumn of 1941, young Petr Ginz of Prague wrote in his diary:

It is foggy. Jews must wear a badge, which looks more or less like this:

On the way to school, I spotted 69 ‘Sheriffs’....

The etymology of the Star of David in relation to diaspora Jews and eventually the state of Israel is well known. Yet no one is sure of the migratory path by which the hexagram traveled from the musty pages of the medieval Kabbalah onto the chests of American frontier lawmen in the middle of the nineteenth century, to be pinned there, a shiny scarab from exotic lands, in the form of a sheriff’s six-pointed star badge. Heading west across the Atlantic, across the trigonometries of Pierre-Charles L’Enfant’s Washington DC and passing close by the early masonic lodges and synagogues of the original colonies, the trail cools as the destination approaches. Who commissioned the first sheriff’s badges? Where were they used? Who designed and made them? Scholarly sources are nearly silent on these questions.

Some badge collectors suggest that early American sheriffs cut the simplest shapes they could by hand from scrap metal or Mexican coins. Such an immaculate conception of the hexagram as a sign of authority in the untamed western territories would constitute a profound and improbable coincidence. More probable is the notion that frontier lawmen imitated the star medallions of knights or English bobbies.

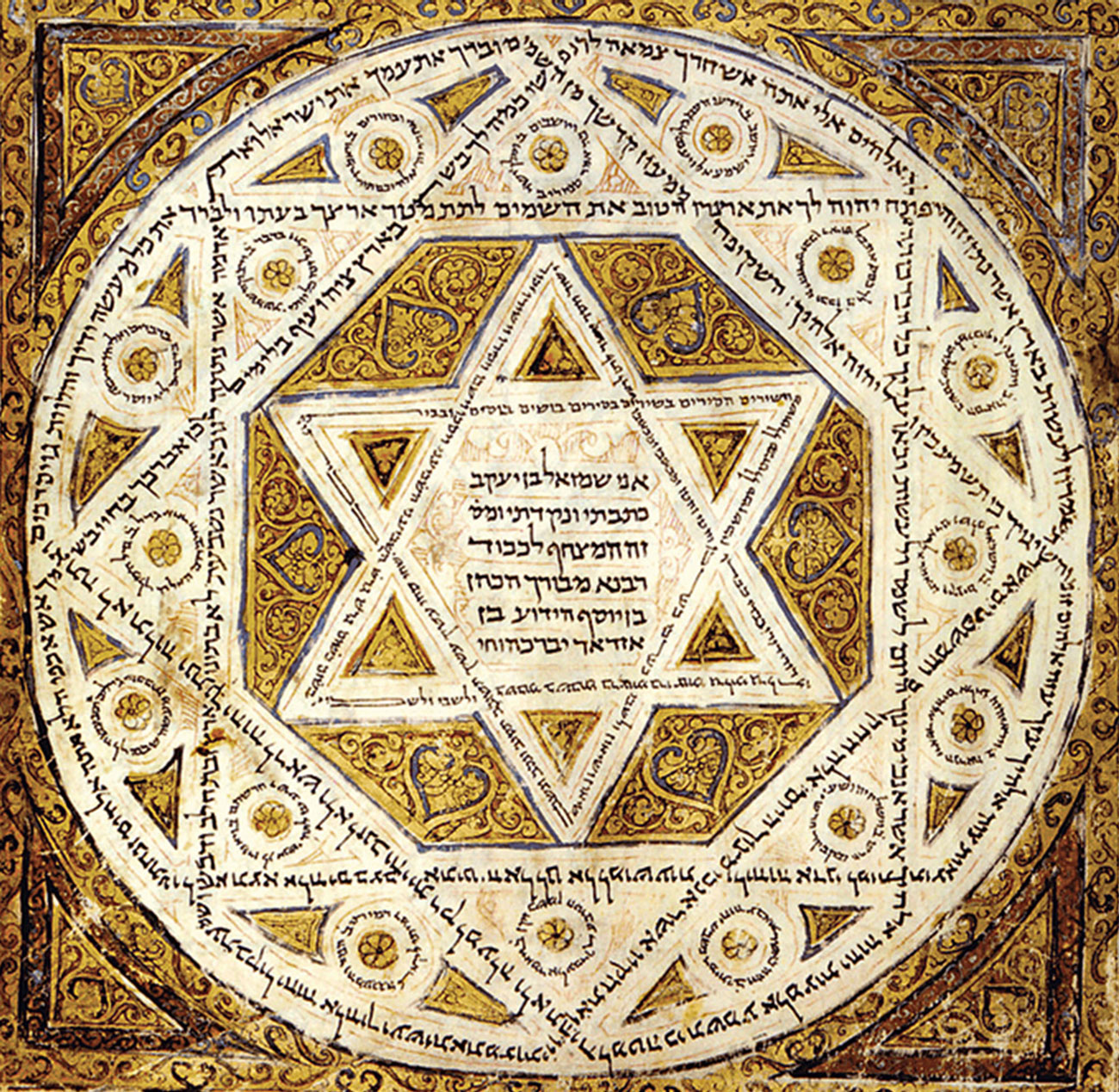

It is difficult to name a symbol more venerable or ubiquitous than the hexagram. Starting around 950 BC, it was put to use by every prominent monotheistic tradition long before it was fetishized by costumed American boys grasping cap guns. Sheriffs still wearing the six-pointed star might be amused to learn that it has been used on distant continents to control thunder, envy, poisoning, sudden death, evil spirits, despair, poverty, and snake bites—a “personal device” and magic diagram designed to keep natural and supernatural forces in check.

This rich history makes it safe to assume that the US Sheriff’s hexagram badge does in fact have a pedigree, though one that has been obscured by poor record-keeping and pulp fiction static, leaving a sort of royal orphan on the doorstep. No predecessor has claimed paternity, but strong family resemblances are not difficult to find.

The astonishing powers of Jerusalem’s King Solomon—purported to control evil spirits, the weather, and animals—were so closely associated with his signet ring bearing a hexagram inscription that the symbol is widely known as the “Seal of Solomon.” Solomon’s father, King David, is also said to have benefited from the protective influence of the hexagram in his duel with Goliath, and likewise lent his name to the “Star of David” or “Magen [shield of] David.” Legends suggest that skillful exploitation of the six-pointed star helped both father and son to unify rival communities in a desert environment where armies and courts could not offer timely relief. Mystical rabbinical texts carried the hexagram forward as a sacred diagram meant to encrypt and preserve the unspeakable name of the Hebrew god.

Hinduism treats the sacred hexagram (satkona yantra) as a trap or container for demons and associates it with the Dionysian god Kataragama. Like David and Solomon, Kataragama had sovereignty in wild, insecure spaces beyond the margin of civilization where roguish behavior, intoxication, subversive activities, and a blurring of normal boundaries were commonplace. The two interpenetrating equilateral triangles of the hexagram resolve tensions between opposites—male and female, rational and instinctive, fire and water, human and divine. The same theme of integration and resolution explains the appearance of the hexagram in the Buddhist Tantric mandala of Vajravarahi.

When operating along the fluid edges of human experience, the need for mastery has been traditionally mediated by a six-pointed star. Often wielded as an engraved talisman in a permanent material, like Solomon’s famous ring, the hexagram can stamp itself onto other objects or bodies as an identifying seal or brand. German provides firm linguistic connections between supernatural powers (hexen: to cast a spell; Hexe: witch), the number six, and its geometric representations. When German settlers established farms in Pennsylvania, they shielded livestock from disease and fire by marking their barns with star-shaped “hex” signs, “as sure in their efficacy as anything in life may be,” one regional scholar suggested.

American freemasons shared this confidence in the hexagram’s utility, borrowing it frequently for ritual purposes and the design of advanced degree medallions—such as the Royal Arch degree of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry. By the late-eighteenth century, the Great Seal of the United States incorporated the hexagram, owing to the strong masonic affinities of the founding fathers.

By the first half of the nineteenth century, western expansion gained momentum due to the Louisiana Purchase and the promise of cheap farmland. Resources and property needed protection, but the terrain was vast, and development of a legal infrastructure lagged behind commercial investment. Interim solutions were needed; the sheriff’s office was a ready tool, and the nation’s most powerful men were familiar with the sacred geometry of the hexagram. Here, several branches of the orphan’s hypothetical family tree became intertwined.

Consider Baltimore, Maryland, where Scottish Rite Freemasonry was introduced in the late 1780s by Joseph H. Myers, a prominent Jewish member of the Royal Arch degree. A National Masonic Convention was hosted by that Royal Arch Chapter in 1843, about the same time America’s first architectural hexagram appeared on the city’s Lloyd Street Synagogue. By 1853, Baltimore police officers were among the first in American cities to wear star-shaped badges. The Baltimore & Ohio Railroad was completed in the same year, providing Baltimore’s traders—especially Jewish wholesale and retail merchants—with unprecedented access to expanding western markets. Hexagram, symbolism, medallion, and a keen interest in effective law enforcement on the frontier converged neatly in Baltimore, one of several possible points of departure for the westward migration of the six-pointed star. Whether the sheriff’s badge received complimentary one-way passage on the B&O may never be known.

For certain, it was precisely in the decades after 1850 that the six-pointed star made its western debut as hundreds of newly appointed sheriffs gamely confronted train robbers, horse thieves, fugitives, unreconstructed veterans of the Confederate Army, and natural hazards on the frontier. They did their work armed only with a six-shooter and a magical six-pointed star diagram. It was said then that there was more law in the Colt six-gun than in all the courts combined. Did sheriffs and their patrons hope that an ancient occult talisman might tip the balance? Did the snakes, rebels, and robbers feel some other kind of awe when the six-pointed star reappeared in the wilderness, with its immutable mandate?

Jon Calame is a partner with Minerva Partners, a non-profit consultancy group focused on quality in the built environment. He specializes in post-conflict urban rehabilitation. His book, Divided Cities: Belfast, Beirut, Jerusalem, Mostar & Nicosia, will be published by the University of Pennsylvania Press in early 2009.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.