Subterranean Foes

The fighting women of the Cu Chi tunnels

Erik Pauser

Right next to the highway, some miles from Cu Chi, stands a small green house with a yard paved with stones. Next to it, under a bamboo awning, is a store that sells canned food, fruit, combs, dried squid, and a bit of everything else. An older woman, Nho, sits with her young daughter beside her, teaching her a song. It is hard to imagine that this woman was once a highly decorated soldier in one of the few women guerilla groups that fought in the American War. During the war, Americans were not the only ones to tally the body count. The National Liberation Front, for which the US Information Agency coined the disparaging name “Viet Cong,” had passed a decree that anyone who killed three American soldiers would be awarded a “One-Star Military Victory Medal”; a two-star medal for six kills; and a three-star medal for nine. Later, when the young girl sings me her new song, someone translates it for me and I find out that it was a popular war song about killing the enemy at whatever cost.

Nho is waiting for her friends Houng and Suong. For eight years, they lived and fought together in the approximately 250-kilometer-long Cu Chi tunnel system just outside Saigon. Together, they are planning a memorial for their friend Ne, who died in 1968 at the age of twenty. They have chosen the anniversary of her death to remember all their friends from the women guerilla group who did not survive the war.

Nho serves green tea to her guests. “Our women’s division was established in November 1965,” she tells me. “The first two to join were Ne and me. We then went to all the villages in the Cu Chi district and looked for women who were brave enough to join our guerilla group. The first person we asked was Suong here. We went to her house and asked her mother for permission. That’s how Suong became the first to join us.”

When Nho tells of asking Suong’s mother for permission, Suong smiles shyly and is momentarily transformed from an older woman into a young girl. Nho continues: “We fought together for a long time, and Ne and I promised to be sisters forever. After the war, I asked her family for a photo to put on an altar at home. And tomorrow we will commemorate her death.”

Women fighters are not new in Vietnam. They occupy an important role in Vietnamese history and have also generated a number of myths. Trung Trac, for example, led the first great uprising against the Chinese in 40 AD together with her sister and Phung Thi Chinh, another female warrior. According to legend, the latter gave birth during a battle and then continued to fight with the child on her back.

In reality, however, the women in the American War had to endure many hardships in order to be seen as equals to their male counterparts. They needed to prove that they were as skilled, and as ruthless. They were teased by the men for having “soft hands and legs.”

We walk slowly through the forest to see a part of the tunnel system that served as their base during the war. Nho says, “I often get so sad that I can’t sleep when I think of the women who fought with us and are now buried in the ground. We sacrificed our youths fighting here in Cu Chi. We were all between eighteen and twenty when we joined the group. Normally, fighters received military training, but many of the girls were shown how to aim and shoot with a rifle and then sent right into battle two weeks later. Many of them died on their first mission.”

The women study the only existing photo of their guerilla group. A war photographer took the picture close to a tunnel that at that time functioned as their base. In the photo, a group of young women sit in a circle, guns over their shoulders; hand grenades lie on the ground in front of them.

• • •

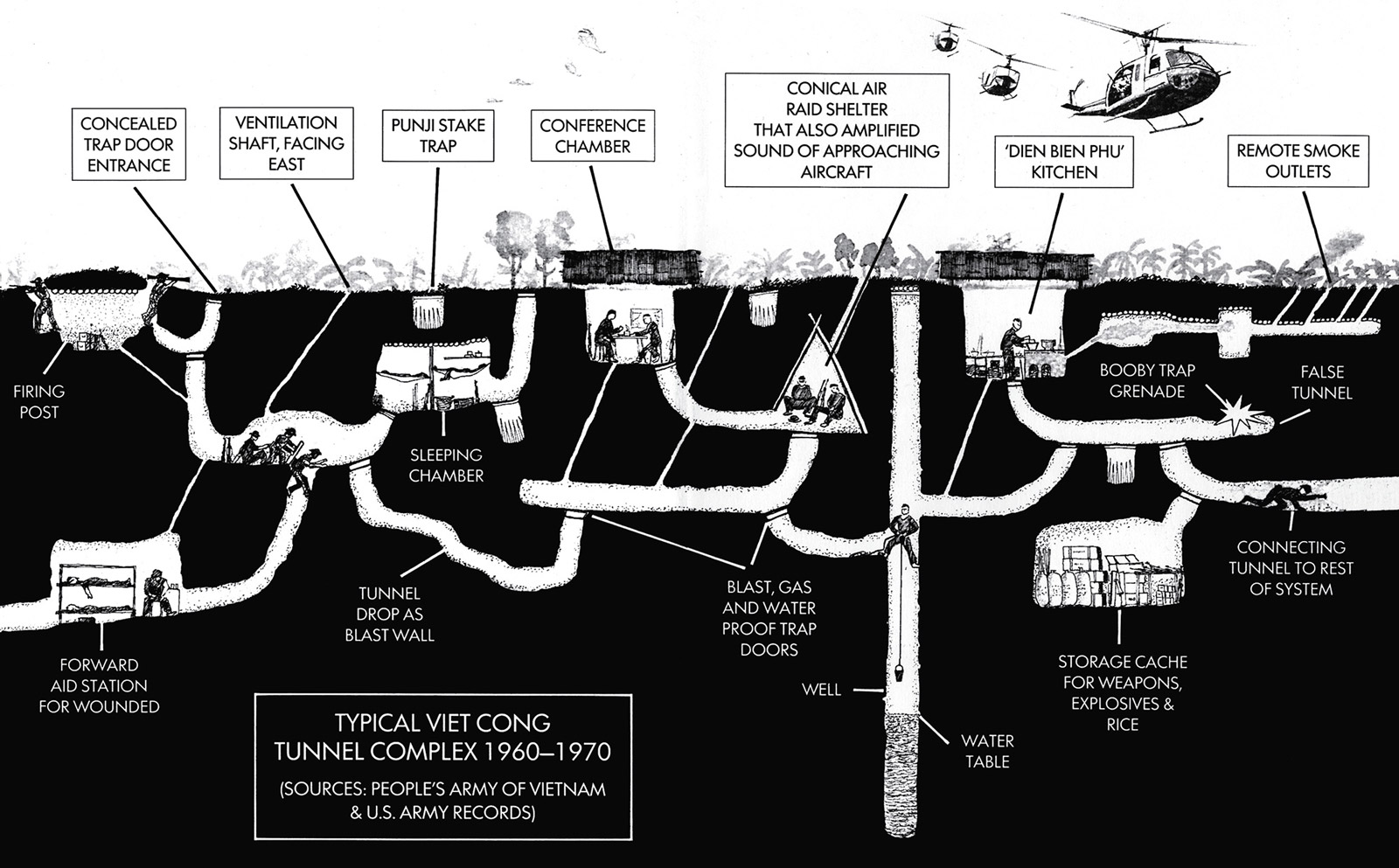

The district of Cu Chi was of crucial strategic importance in the war because the major supply routes in and out of Saigon passed through it. The tunnels in Cu Chi were the most developed part of a gigantic underground network that, at the height of the war in the mid-1960s, stretched from the outskirts of Saigon almost to the Cambodian border. Thousands of kilometers of tunnels connected villages and provinces. Some tunnel networks contained operating rooms, weapons factories, arsenals: everything one needed to wage war. Some were even equipped with kitchens, schools, and theaters. But most of the tunnels were just narrow winding corridors without any amenities. Life in the tunnels was difficult. Air quality was poor, and sometimes combatants stayed below ground for days and weeks without light or sufficient nourishment. Originally dug as hiding places for nationalist guerillas fighting the French in the 1940s and 1950s, the old tunnels were repaired and put back into use after 1960. There was no overall plan for the tunnels; they grew organically in response to the changing needs of the local guerillas who struggled to meet the threat of a highly technologized superpower with comparatively unlimited stores of airplanes, bombs, artillery, and chemical weapons.

In 1965, General Westmoreland decided that a series of strongly fortified bases were needed around Saigon. The areas for proposed sites of the camps had to be cleared and secured first, and so early on the morning of Friday, 7 January 1966, US forces kick-started Operation Crimp. At the time, it was the war’s single largest military operation. It was preceded, as usual, by artillery fire and bombing. Westmoreland’s plan was to deploy helicopters, tanks, and over 8,000 men to overwhelm and eliminate the NLF in the Cu Chi region and in the adjacent “Iron Triangle,” a stronghold of the resistance against the French and later against the Americans. This turned out to be easier said than done. From the moment US soldiers alighted from their helicopters, they were shot at and killed by an enemy whom they could not locate. From bunkers that held one or two people, the guerillas could fire off shots through a small peephole, escape through a tunnel, and then pop up elsewhere.

The US Army transformed large areas of Cu Chi into a desert. Farms and harvests were burnt; bulldozers felled the forest. Chemical weapons poisoned the streams and made it impossible to grow anything edible in substantial quantities. Save for a few strategically located villages, the land was scorched to produce a “free-fire zone” in which US military personnel could fire their weapons without permission from headquarters.

US forces proceeded quickly to build their fortified bases, protected by impenetrable barbed wire barriers. Much to their surprise and frustration, however, the guerilla attacks continued. The tunnel system ran right beneath several of their bases. The NLF could choose where and when they wanted to strike. Their tactics were dictated by their technological and material inferiority: ambushes, sniper attacks, and booby traps became their way of meeting the threat. The tunnels was the network through which these activities could be maintained.

The US launched many other initiatives to destroy the tunnels, including using so-called “tunnel rats”—soldiers who would enter the tunnels, often alone because of the width of the passageways, and slowly make their way through them to either kill the enemy or to plant explosives. None of the initiatives was successful and the tunnels continued to function until the end of the war.

• • •

It is damp and warm, and we are immediately engulfed in total darkness when we climb down into the entrance of the tunnel system. Suong says, “It’s hard to describe, but what touches me most is that we are still alive and can gather here and think about the past. It awakens so many feelings when I think about how we lived and fought in these tunnels for so long. It’s the most precious and remarkable thing that has happened to me.”

“It was like magic,” adds Nho. “When the enemy came, we disappeared into a tunnel and came up somewhere else. That is how it was day after day. It felt like we would never live above ground again. Despite this, we were so happy when we managed to carry out our duties. Under the most difficult conditions, we, the women, managed to succeed in very difficult assignments. It made us very proud.”

I ask Nho how they handled bombings. “We could take on the B-52s. When we got news that they were about to bomb, we would all gather at the entrances of the tunnels. There was more room there, not like in here where we are under so much soil. If a bomb from a B-52 fell on a tunnel, it would cave in and bury us in there. But if we stayed by the entrance, we would not be buried alive. The danger was that the B-52 would score a direct hit on us, but then we would at least not die in a tunnel. After every bombing, when it was quiet again, a group of us would immediately run to help whoever was injured.”

“Sometimes the American reconnaissance units would come with their dogs,” Suong continues, “which had been trained to sniff for tunnels. When we would hear about the ‘tunnel rats’ coming, we’d scatter grilled chili peppers around the tunnels. When the dogs got the chili in their noses, they couldn’t distinguish between scents any more. We had many different strategies, including booby traps and tiger pits, which were pits with bamboo spikes at the bottom. Many of the ‘tunnel rats’ died before they got close.”

We sit in a circle outside a tunnel entrance. Nho hands me a bottle of water. “The tunnel system was already here when I was a little girl. I don’t now who started to dig them. When I was sixteen, I already knew about them because I’m from Du Duc. During the resistance against the French, the tunnels were wider and taller. We could even stand up in them and run. But the French didn’t have modern weapons and bombs. When we fought the Americans, we got orders to dig lower and narrower tunnels that would not cave in so easily when bombs fell on them. As a little girl, I helped dig the tunnels. The whole village gathered to dig, all the farmers, the young and the old, women and men. If we heard news that the enemy was close by, we all descended into one house and came up in another. You could go from house to house, village to village, commune to commune—the tunnels were interconnected. It’s hard to imagine how we lived. The Americans bombed and threw grenades non-stop. We would not change clothes for days. We ate rice balls and only drank the water we carried with us. Sometimes, we remained in certain positions in the tunnels for long periods of time.”

Suong remembers a time when a group of US soldiers stepped on a mine. “After the explosion, the American paramedics came running in. They were holding their dying friends who were screaming in pain. I remember thinking how young they all were and how they must have been forced to come to Vietnam. After they retreated, we came out to see if there was anything we could salvage. We were young and playful back then. We used to poke fun at each other a lot. We found an American soldier’s leg and we picked it up because we thought it would start to stink if we just left it there. The shoe was still on it; the foot was blue. Our skins crawled when we saw it, but we started to make jokes: ‘Someone forgot his leg!’ All the way back to camp, we made fun of the girl who was carrying the leg. ‘What kind of war booty do you have there! So much to pick up and you decide to take a leg!’ We laughed a lot. When we were scared, we usually joked around. And when one of us died, we would be so sad but we would not let ourselves cry. We called it ‘the tears that run within us.’”

• • •

Vo Nguyen Giap, North Vietnam’s legendary general in the American War, once said of the many casualties on his side that “every minute, hundreds of thousands of people die all over the world. The life or death of a hundred, a thousand, or tens of thousands of human beings, even if they are our compatriots, represents really very little.” In an interview in Hanoi after the war, he was asked how long the Vietnamese could have continued to fight. He answered, “Another twenty years, even a hundred years, as long as it took to win, regardless of cost.”

Erik Pauser is an artist and filmmaker based in Stockholm. His films have won awards at a number of festivals, including Nordic Panorama, the San Francisco International Film Festival, and FICA Brazil. He is currently working on The Face of the Enemy, a film and installation constructed from two hundred hours of interviews with Vietnamese veterans of the war with the United States. For more information, see www.erikpauser.com.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.