Mannequins, Manners, and Mutilation

Window-shopping in Iran

Nina Power

The human form is, at best, an eerie object. At one remove, however—the doll, the mannequin, the puppet—it becomes even stranger. The more lifelike the representation, the more likely we are to flinch when we realize that there’s no human content to the misleading form. Despite this power to disrupt our need to categorize—human, not human—we have become used to these static projections of ourselves. The horror felt toward the golem, the toy gone insane, or the statue brought to life belongs to another time, an age when the animisms of the heart hadn’t been replaced by the realization that fear comes far less from beyond than from the monstrousness of humanity itself.

In a sense, we have become accustomed to these plastic, fiberglass, and rubber impersonations, even if Hans Bellmer’s poupée, in its disturbing anatomical impossibility, occasionally reminds us of what we’re trying to ignore. Little girls push strollers containing miniature versions of themselves; adults keep remnants of their childhoods on shelves, as if reassured by their presence. Most familiar of all, perhaps, are the grown-up dolls used to sell us both the clothes they silently advertise and the image of the body beneath. The mannequins in the shop window are not there to be seen as such, which is why we laugh when we catch a shop worker in the middle of changing a mannequin’s outfit—how silly the sexless dolls look! The moment of catching commerce in the act also has a kind of obscene dimension—the Emperor’s new clothes look even dafter on human copies.

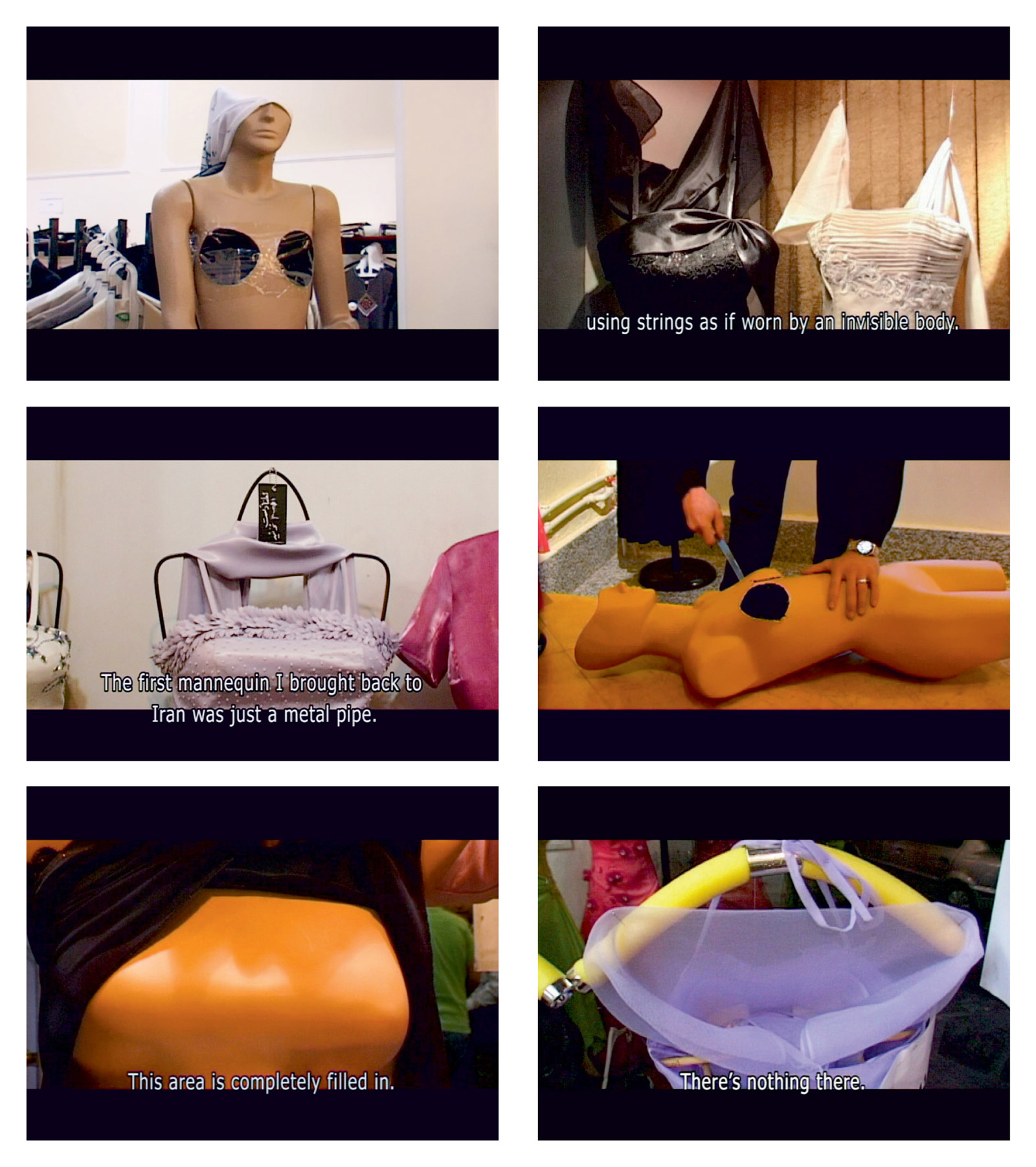

But what if the mannequin of everyday commerce became an object of contention, of controversy, even? This is the story behind Firouzeh Khosrovani’s 2007 documentary, Rough Cut, which recounts the agitation that mannequins are causing in Iran. Although there are no strict rules about how the human form may be represented in the Islamic Republic, government officials charged with defending “morality in public places” have found fault with displays in shop windows, accusing retailers of breaching Koranic edicts against the display of the human, particularly female, form. Stores are closed down for days on end, and the government makes endless demands that mannequins be removed or adjusted in order not to arouse.

Rough Cut traces the post-revolutionary history of the shop-front dummy, from the metal pipes with cross-bar shoulders used in the 1980s to the fiberglass dolls of the post Iran-Iraq war period when “things opened up a bit,” according to the narrator. But the more realistic the mannequins became, beginning with heads and torsos and followed by detailed legs and hands, the more trouble they caused. Rumblings from on high began to be heard about legal regulation of these fiberglass replicas of the human form, and soon the more realistic designs began to change, either by explicit order or from fear of reprisal: the half-heads, absent limbs, and, most significant of all, sawn-off breasts everywhere drew attention to the non-realism of these artificial bodies. The acceptable version of the female form became a kind of damaged man.

The “ghost mannequin” can’t eliminate the discomfort created by the empty inhuman form. It is this same desire to fill in the reflection with knowledge that haunts Heinrich von Kleist’s 1810 short story “On the Marionette Theater,” where the narrator’s friend, who has recently been appointed principal dancer at the local theater, tries to convince his interlocutor that the movement of the marionettes is infinitely more graceful than that of human beings. The piece concludes with the following reflection on the part of the dancer:

“Now, my excellent friend,” said my companion, “you are in possession of all you need to follow my argument. We see that in the organic world, as thought grows dimmer and weaker, grace emerges more brilliantly and decisively. But just as a section drawn through two lines suddenly reappears on the other side after passing through infinity, or as the image in a concave mirror turns up again right in front of us after dwindling into the distance, so grace itself returns when knowledge has, as it were, gone through an infinity. Grace appears most purely in that human form which either has no consciousness or an infinite consciousness. That is, in the puppet or in the god.”

Between the puppet and the god, between the absence of consciousness and infinite thought, lie the finite reflections and creations of man—the puppet-maker, doll-maker, and mannequin designer who nevertheless do not always feel at home in the world of their inventions. The shop-front dummy offers a vision of a humanity devoid of knowledge, a pure statue embodying the absence of thought. As Kleist’s narrator puts it: “Certainly, I thought, the human spirit can’t be in error when it is non-existent.”

For all the disquieting properties of mannequins, the temptation to render oneself doll-like is a strange but persistent theme in our past, and perhaps even more so in our present. Iran’s concern over the mannequins coincides with high levels of plastic surgery in the country, as young women attempt to wrest control over their bodies by way of oddly homogeneous rhinoplasties. The battle over the doll-like tendencies of women, and their naturalness or otherwise, is not a new debate, of course. At the end of the eighteenth century, we find Enlightenment giants squabbling over the suitability of toys as a model for female subjectivity. Kant seems firmly set on the alignment of women with their playthings. Women, according to Kant, barely get beyond tying ribbons, prettifying the domestic sphere, and entertaining an overwhelmingly aesthetic understanding of the world. As he claims in Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and Sublime (1764), “Women will avoid the wicked not because it isn’t right, but because it is ugly. ... Nothing of duty, nothing of compulsion, nothing of obligation. ... I hardly believe that the fair sex is capable of principles.”

Incapable of appreciating the sublime, and consigned to the realm of the boringly beautiful alone, it takes a different (von) Kant, the Petra of Fassbinder’s 1972 film, to restore menace both to relations between women, and, perhaps more profoundly, between women and the mannequins that they resemble and emulate. The cruelty of the girl to her doll in a fit of boredom becomes the model (in both senses) for a sinister adult game of appearance and domination.

While Kant the elder is happy to imagine women as bigger versions of their amoral, if decorative, toys, Mary Wollstonecraft, writing a couple of decades later, is most certainly not. In a section of her Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792) entitled “Animadversions on Some of the Writers Who Have Rendered Women Objects of Pity, Bordering on Contempt,” she takes Rousseau, in particular, to task for his claim in Émile that “the doll is the peculiar amusement of the females; from whence we see their taste plainly adapted to their destination.” Rousseau’s approval of the patterns of child-doll relations nevertheless points to the core strangeness in the supposedly natural relation between girls and their likenesses. As he writes in Émile:

“But she is dressing her doll, not herself,” you will say. Of course; she sees her doll, she cannot see herself; she cannot do anything for herself, she has neither the training, nor the talent, nor the strength. So far she herself is nothing, she is engrossed in her doll and all her coquetry is devoted to it. This will not always be so; in due time she will be her own doll.

“She herself is nothing ... she will be her own doll.” Isn’t this the uncanny suggestion behind the mannequin, that the insubstantial might somehow coincide with a convincing external façade? As a political tactic, the more recent actions carried out by the Barbie Liberation Organization, where the voice boxes of Barbie dolls were replaced with those of G.I. Joe, might smack of infantile (if amusing) frivolity on a par with the toys themselves. On the other hand, pulling the string of a pretty doll and hearing “Vengeance is mine!” could easily be the basis for a whole new genre of schlock horror films, if not a new political education rather different from the one that Rousseau envisaged. Wollstonecraft might even approve.

Another interviewee reports that when he told the authorities, “If we’re going to have a tree trunk instead of a mannequin, why not put a crate of oranges in the window?” they got upset and closed the shop for a few days. The surreal image of a dress covering a crate of oranges points not only to the absurdity of the Iranian situation, but also to the inherent strangeness of mannequins as a whole. Rough Cut finishes with an extract from a poem by Forugh Farrokhzad, perhaps Iran’s best-known female poet of the twentieth century, entitled “The Wind-Up Doll”:

One can be like a wind-up doll

and look at the

world with eyes of glass,

one can lie for years in lace and tinsel

a

body stuffed with straw

inside a felt-lined box,

at every lustful

touch

for no reason at all

one can give out a cry

“Ah, so happy am I!”

The mannequins of Iran are anything but happy, but perhaps this is the fate of all toys forced to bear such a weight of responsibility, be they human or otherwise.

Nina Power is a lecturer in philosophy at Roehampton University, London. She is the co-editor of Alain Badiou’s writings on Samuel Beckett (Clinamen Press, 2003) and has published numerous articles on contemporary politics and philosophy. She is currently writing a book on feminism and capitalism for the newly founded Zero Books, and she is also a member of the film collective Kino Fist.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.