Smoke

Something in the air

Implicasphere

The cloud of associations around a single word is, we assume, contained by a clear perimeter. “Smoke,” though, like its material nature, is roiling and unstable, its boundary perpetually on the move. With interpretations drifting from humors or essences to colored vapors or carboniferous particles in suspension, and from the materialization of the soul to a polluting by-product of the industrial era, smoke’s ever-shifting significance suggests an epistemology that fogs and dissipates. We have followed trails, deciphered signals, read letters in the sky, sniffed bonfires, sampled sweet-salty savories, pumped dry ice at rock gigs, bungled chemistry experiments, been cleansed by smudging and magically vaporized; we’ve rendered our eyes smoky with makeup, had our thatch fumigated and our pests smoked out; we’ve peered into the mouths of dragons and rubbed lamps and wished ... only to clutch at air every time.

Perhaps smoke’s sole reliable qualities are inconstancy and contradiction. It represents immateriality and dissolution, yet its effects are tangible in blackened buildings and lung disease. It is an inconstant ally, a double agent that disappears not quite without trace, as it coats the surfaces of its passage with telltale smears. In novels and movies, bad guys hide behind smoke screens, to be given away by the smoking gun discovered by a detective who smokes out the truth. And although smoke is not exactly formless, the unpredictable logic of its eddies and whorls have occupied geophysicists and computer graphics programmers for decades.

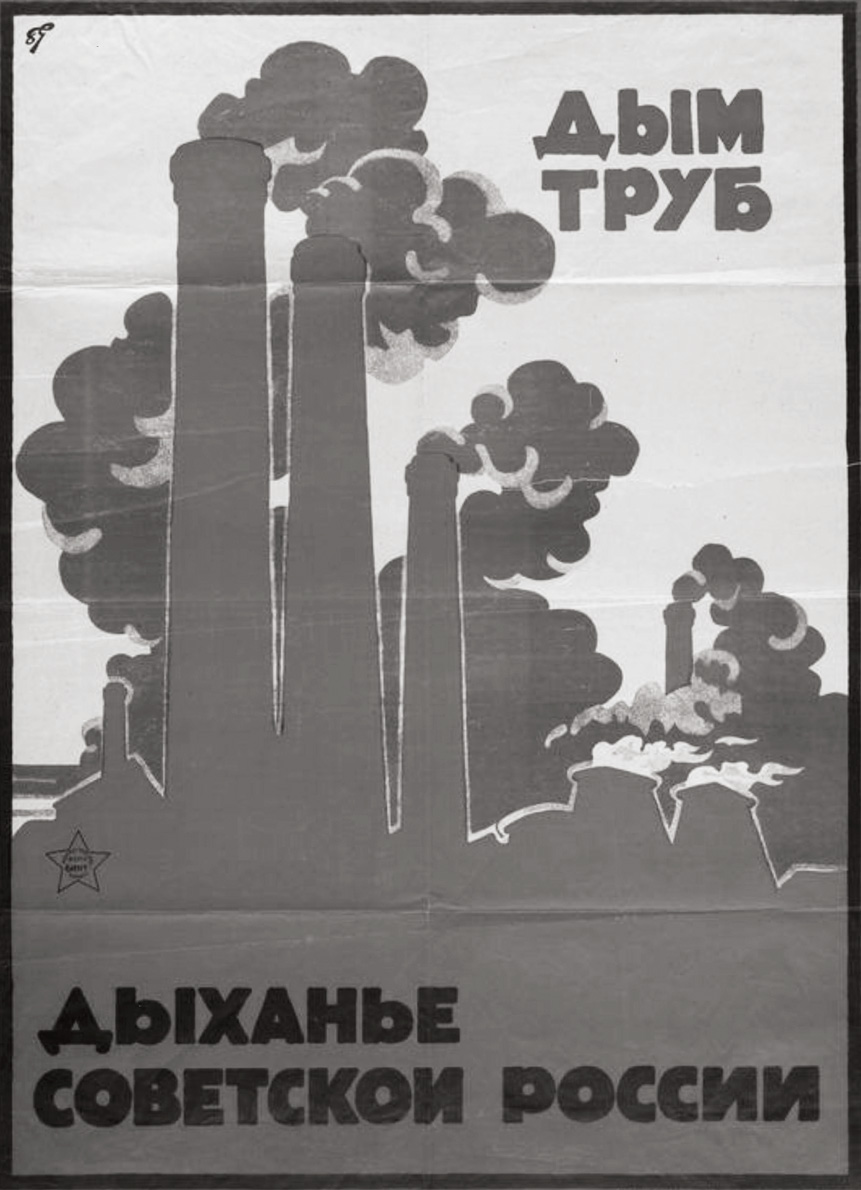

Smoke has plumed and swirled since the beginning of time, but perhaps never more in human history than the modern age of empire. In London, smoke was once a symbol of progress, from the fug of its Enlightenment coffee salons through to its mighty industrial-imperial moniker “The Big Smoke.” But it recently reached a suffocating density: even as late as 1952, thousands died from the effects of the capital’s last great pea-souper smog. Now, in certain old industrial cities, with their smokeless fuels and smoking bans, smoke is gradually vanishing from fireplaces and fingertips: smoke seems to be going up in smoke, becoming its own metaphor. But while smoke fades over some European metropolises, it rises in vast volumes from Amazon forest clearance fires, from China’s new coal power plants, and from war zones around the world.

This issue of Implicasphere seeks to rescue the neglected smokes that threaten to get lost in the miasmic pall: the puffs and wisps that issue from marginal quarters such as stage illusions, deep ocean lava beds, and the names of plants. We have found smoke to be a sign of life—from the belching volcano or comforting cottage chimney—as well as a billowing flag in the winds of destruction.

The original settlers had to find names for the fields and streams and mountains of their new land. They named some for the places they had left in Norway, used a few Celtic names such as Patreksfjördur, and coined others to fit the characteristics of the new land. For example, they used reyk, actually smoke, to name the places where, in this land of volcanoes and geothermal vents, they saw steam rising from the earth, as in Reykholt (smoke hill) and Reykjavík (smoke bay/cove).

—Terry G. Lacy, Ring of Seasons: Iceland—Its Culture and History (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2000).

A locomotive is moving. Someone asks: “What moves it?” A peasant says the devil moves it. Another man says the locomotive moves because its wheels go round. A third asserts that the cause of its movement lies in the smoke which the wind carries away.

The peasant is irrefutable. He has devised a complete explanation. To refute him someone would have to prove to him that there is no devil, or another peasant would have to explain to him that it is not the devil but a German, who moves the locomotive. Only then, as a result of the contradiction, will they see that they are both wrong. But the man who says that the movement of the wheels is the cause refutes himself, for having once begun to analyze he ought to go on and explain further why the wheels go round; and till he has reached the ultimate cause of the movement of the locomotive in the pressure of steam in the boiler, he has no right to stop in his search for the cause. The man who explains the movement of the locomotive by the smoke that is carried back has noticed that the wheels do not supply an explanation and has taken the first sign that occurs to him and in his turn has offered that as an explanation.

The only conception that can explain the movement of the locomotive is that of a force commensurate with the movement observed. The only conception that can explain the movement of the peoples is that of some force commensurate with the whole movement of the peoples.

Yet to supply this conception various historians take forces of different kinds, all of which are incommensurate with the movement observed. Some see it as a force directly inherent in heroes, as the peasant sees the devil in the locomotive; others as a force resulting from several other forces, like the movement of the wheels; others again as an intellectual influence, like the smoke that is blown away.

So long as histories are written of separate individuals, whether Caesars, Alexanders, Luthers, or Voltaires, and not the histories of all, absolutely all those who take part in an event, it is quite impossible to describe the movement of humanity without the conception of a force compelling men to direct their activity toward a certain end. And the only such conception known to historians is that of power.

—Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace, trans. Rosemary Edmonds (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1978).

Our Author expresses himself with proper warmth and indignation against the absurd policy of allowing Brewers, Dyers, Soap-boilers and Lime-burners to intermix their noisome works amongst the dwelling-houses of the City and Suburbs: But since his time we have a great increase of Glass-houses, Founderies, and Sugar-bakers to add to the black catalogue at the head of which must be placed the Fire-engines of the Water-works at London Bridge and York Buildings, which (whilst they are working) leave the astonished spectator at a loss to determine whether they do not tend to poison and destroy more of the inhabitants by their Smoke and Stench than they supply with their Water. ...

Till more effectual method can take place, it would be of great service, to oblige all those Trades who make use of large Fires, to carry their Chimneys much higher into the air than they are at present; this expedient would frequently help to convey the Smoke away above the buildings, and in a great measure disperse it into distant parts without its falling on the houses below. ...

A method of charring sea-coal, so as to divest it of its Smoke, and yet leave it serviceable for many purposes, should be made the object of a very strict inquiry and Premiums should be given to those that were successful in it. Proper indulgences might be made to such Sugar, Glass, Brew-houses, &c. as should be built at the desired distance from town; and the building of more within the City and Suburbs prevented by law: This method, vigorously persisted in, would in time remove them all.

—John Evelyn, Fumifugium: or, The Inconvenience of the Aer, and Smoake of London Dissipated. Together with some Remedies humbly proposed by J.E. Esq; To His Sacred Majestie, and To the Parliament now Assembled (London: Gabriel Bedel & Thomas Collins, 1661).

Episode

Holy...

Detail

1–16

Smoke (officer)

as police find the duo, Robin repeats “… or that’s just what we will be, just Holy Smokes!”

1–02

Smoke

Batman blows a hole into Riddler’s lair

1–28

Smoke

Tut turned on the Batsmoke

1– 25

Smokestack

The duo are placed in a room with a 50-foot smokestack

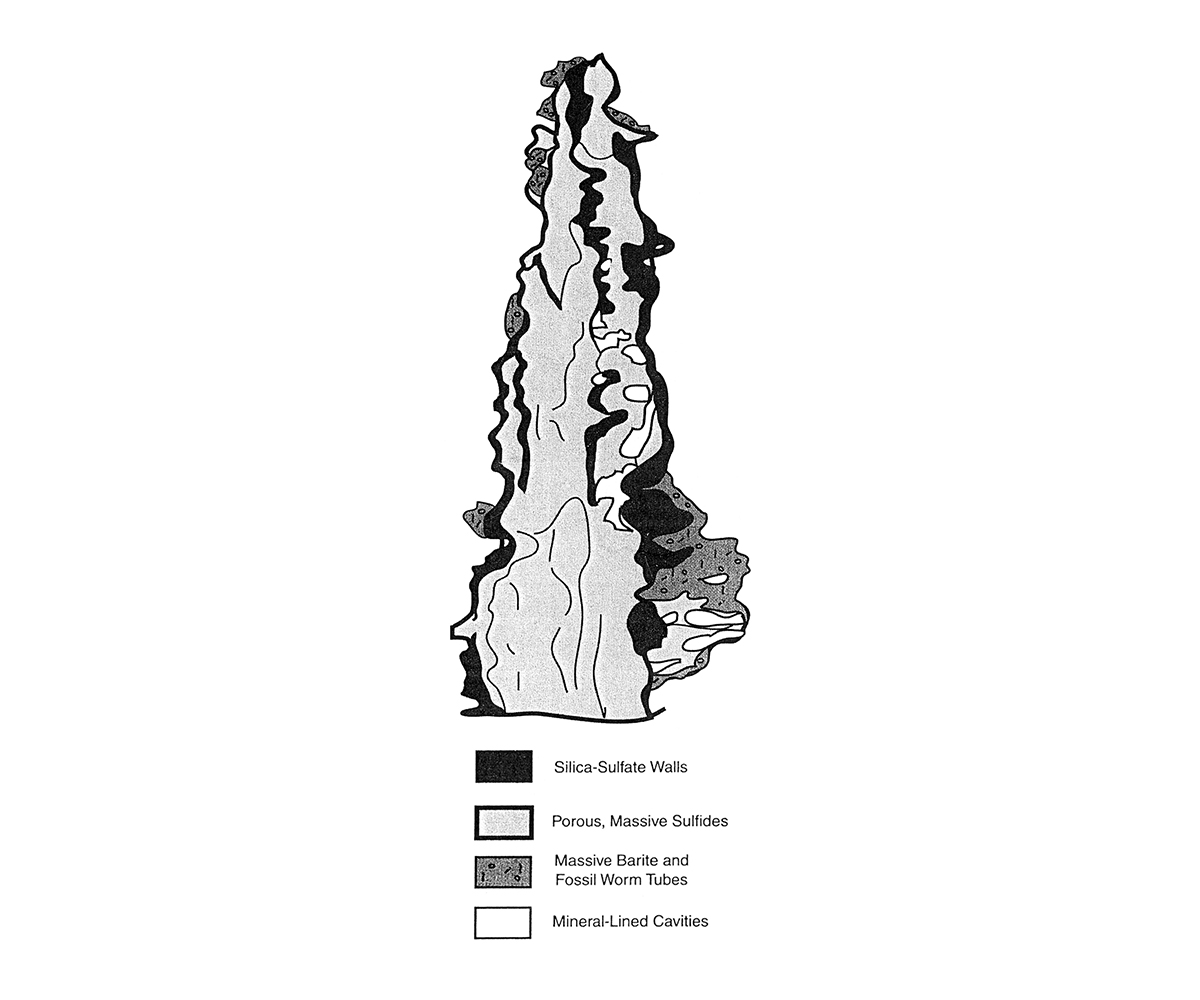

At the first site dew sulphide deposits, obviously the work of hot water, excited the two geologists. Foster did not want to linger; he had seen better examples on previous dives. As he drove over fresh lava flows toward the next site, he began to notice small white crabs on the horizon. They reminded him of similar scenes he had witnessed in the Galápagos Rift. Yet as he entered this second vent field, it didn’t feel the same as others he had seen. He passed a cluster of dead clams; there were not as many living creatures as usual. The water seemed cloudier than usual. Suddenly, a chimney-like spire about six feet tall came into view, with a dense black fluid billowing from its top. Foster told the surface crew it looked like a locomotive “blasting out” stuff, which resembled black smoke. Clearly the water nearby was warm, and maybe hot; it shimmered. But how hot?

As Foster brought [the submersible] Alvin closer, he found the manoeuvring difficult. Something was pulling him into the roiling black cloud.

That pulling force proved to be the updraft, or chimney effect, caused by the rising black fluid. As this heated water gushed upward, the “black smoker” was pulling cooler ocean water in from all sides. And since Alvin was neutrally buoyant, it was also going along for the ride—straight towards the center of this strange volcanic outburst.

—Robert D. Ballard with Will Hively, The Eternal Darkness: A Personal History of Deep-Sea Exploration (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000).

The big chimney said to the little chimney, “You’re too young to smoke.”

—Traditional

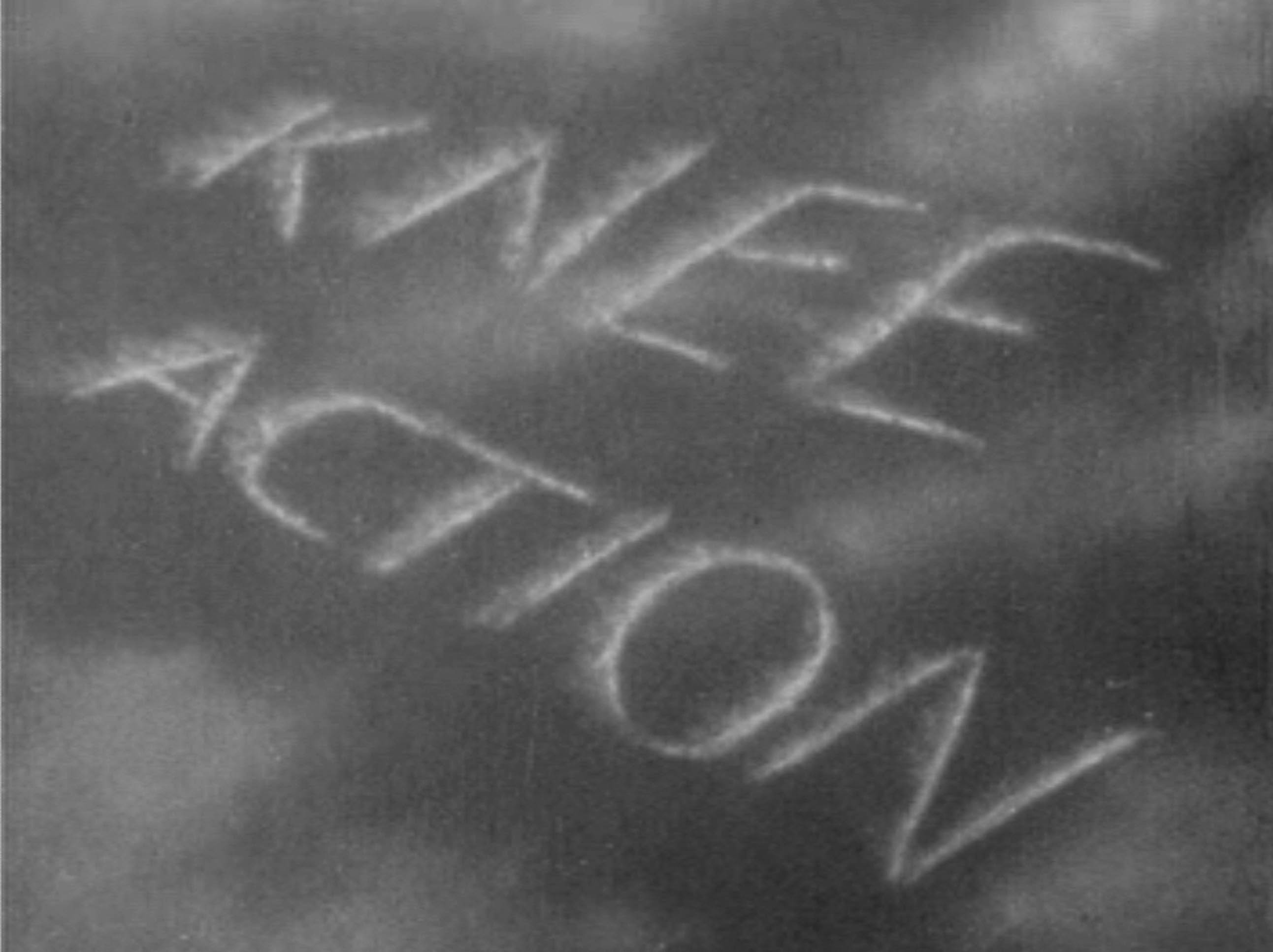

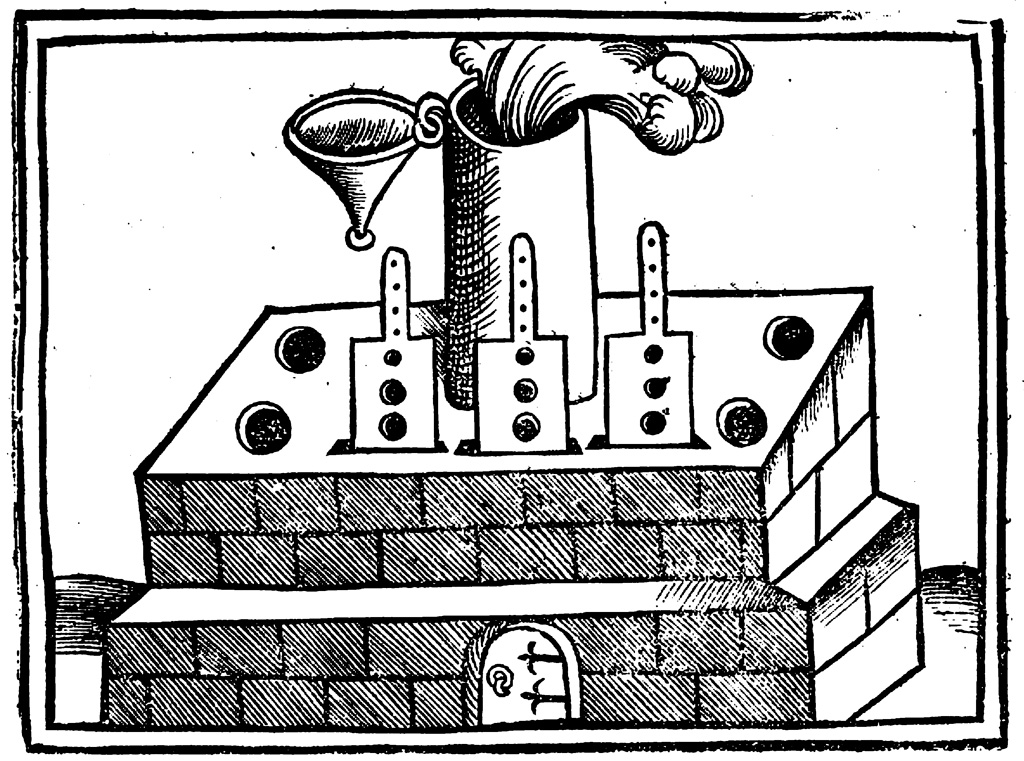

The ancient projection methods which were to influence the phantasmagoria showmen also included the use of mirrors and the camera obscura. In the book of Daniel we are presented with an Old Testament account of the sudden appearance of strange writing on a wall during a banquet held by the Babylonian king, Balshazzar. The “letters of fire” slowly revealed itself as though written by an invisible hand, but is now universally thought to be the result of a simple trick with a mirror, the prophecy of doom being the reflection made by a bright light on the surface of a smoke-blackened mirror as the sooty deposit was deftly removed by a shadowy finger.

—Mervyn Heard, “The History of Phantasmagoria,” PhD dissertation, University of Exeter, 2001. Available at uk.bl.ethos.366617.

The story of perfume begins with the birth of urban life in the ancient Near East some five thousand years ago. The word “perfume,” from the Latin per fumum, means “through smoke,” and the first perfumes were aromatics kindled as incense to the gods and ancestors. Scented smoke was thought to attract good influences.

Burning incense was believed to connect humans with deities in the heavens by providing a means of carrying prayers aloft. It was also believed that incense’s perfume was pleasing to the gods and that one’s ancestors could derive sustenance from the fumes. For the Mesopotamians, the most prized of all incense varieties was the fragrant cedar of Lebanon (Cedrus libani). Vast quantities of the wood and resin of the tree were imported to Mesopotamia from the forests of the Lebanon, far to the northwest. The ancient Akkadian word lubbunu, meaning “incense,” still lingers in the word “Lebanon.”

The resinous woods of pine, cypress, and fir trees were also burned in public ceremonies and private devotions. All of these woods possess a clean, refreshing scent. Although not a conifer, the evergreen myrtle shrub has a similar clean aroma that was enjoyed in incense. ... Juniper berries, familiar to us today as the source of the odor and flavor of gin, were also prized and used in incense.

—Edwin T. Morris, Scents of Time: Perfume from Ancient Egypt to the 21st Century (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Prestel Publishing, 1999).

London. Michaelmas term lately over, and the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln’s Inn Hall. Implacable November weather. As much mud in the streets as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth, and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holborn Hill. Smoke lowering down from chimney-pots, making a soft black drizzle, with flakes of soot in it as big as full-grown snowflakes—gone into mourning, one might imagine, for the death of the sun.

—Charles Dickens, Bleak House (London: Bradbury and Evans, 1853).

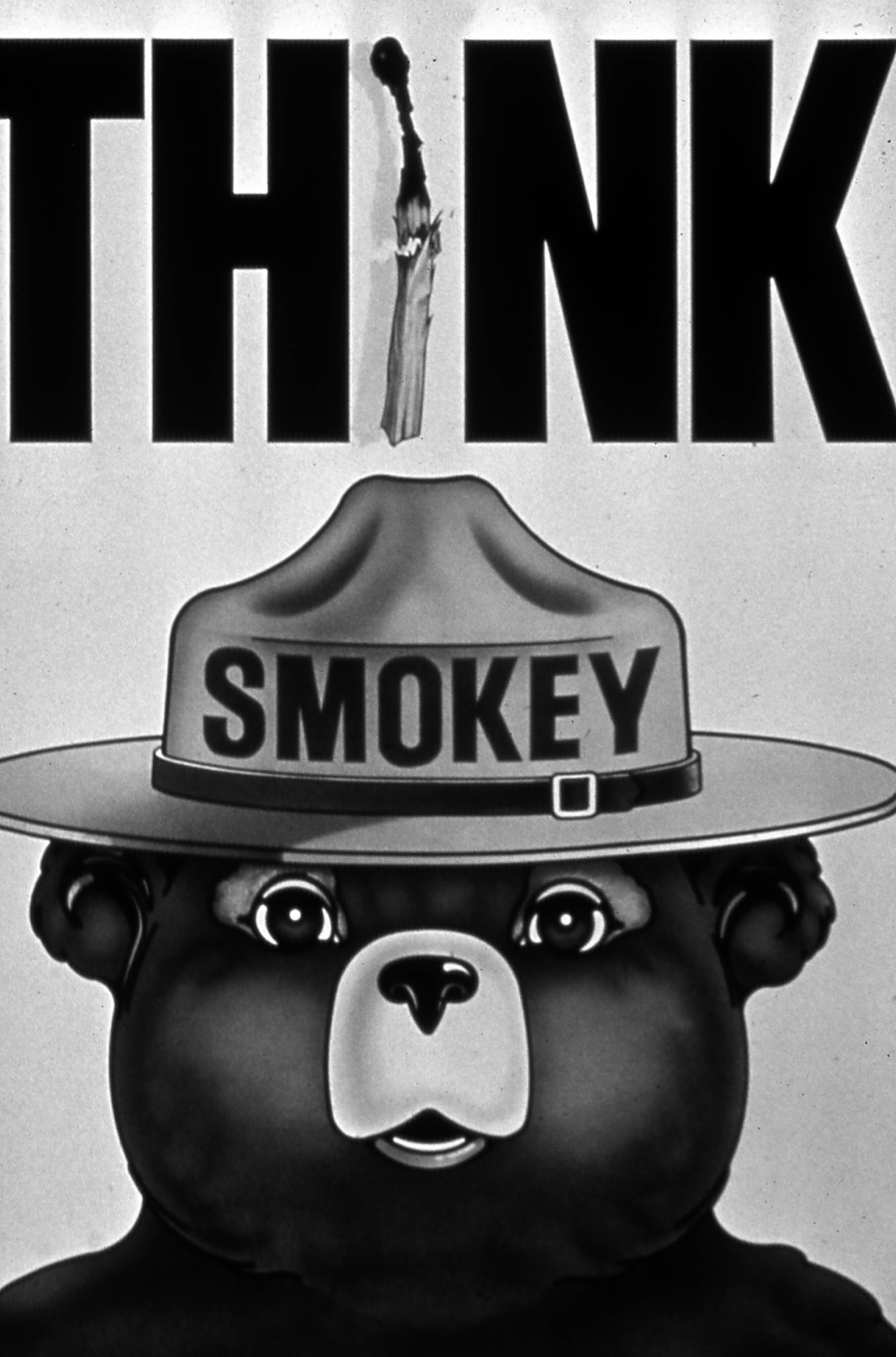

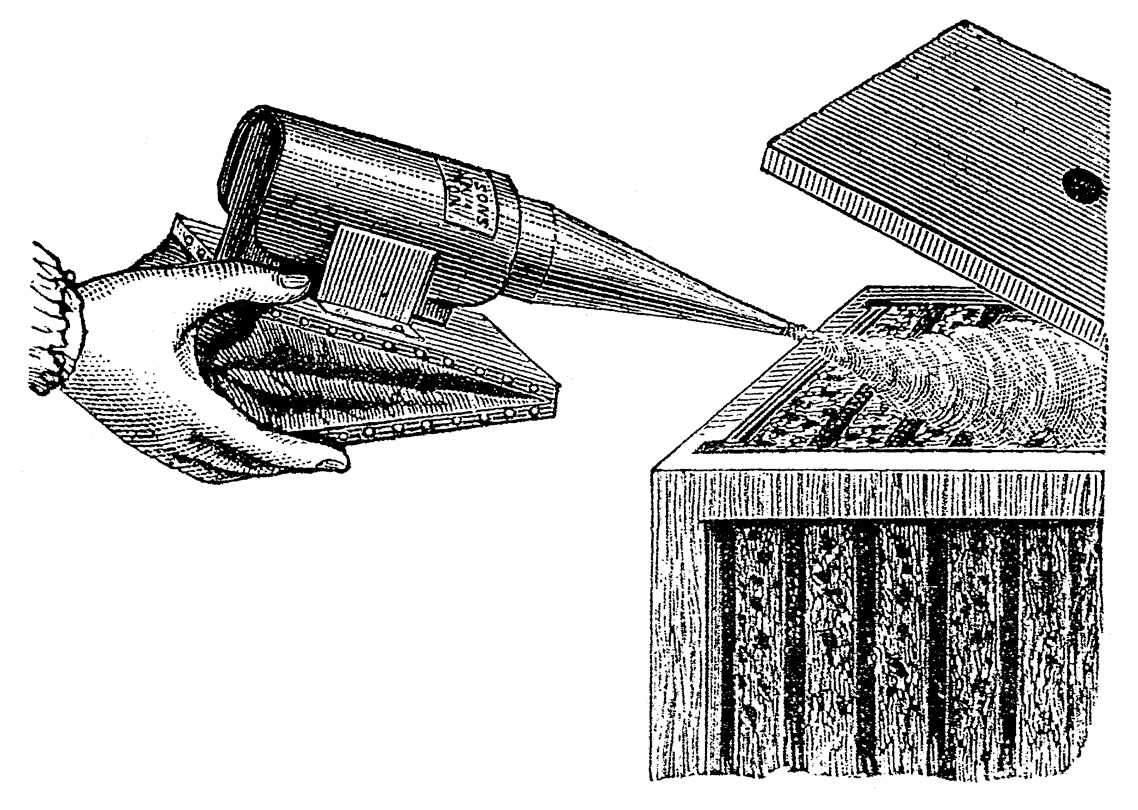

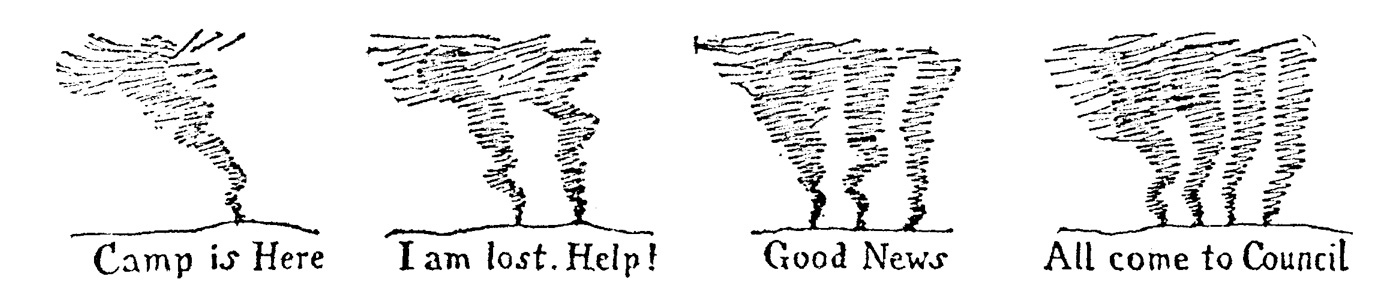

The rows of cards [similar to but much larger than those shown] are hung in line with the chimney under observation at a point of about 50 feet distant from the observer, at which distance the lines of the cards become invisible and the cards appear to be of different shades of gray to almost black. The observer glances alternately at the smoke and at the cards, makes observations continuously for 1 minute, and decides which card most nearly corresponds with the color of the smoke. The record is then made accordingly, noting the time.

SCALE FOR GRADING SMOKE DENSITY:

—James F. Cosgrove, Coal: Its Economical and Smokeless Combustion (Philadelphia: Technical-Book Publishing, 1916).

Infallibility is expected of popes and television anchors, so there was something arresting about the confused scramble to interpret the first creamy wisps of smoke floating from the Vatican chimney yesterday.

“Darned if it doesn’t look darker,” said Charles Gibson of ABC, trying to square the appearance of white smoke with the absence of confirmation from the Vatican bell tower. All the networks went live at the first puff of smoke and as they waited, watched and deliberated (beige? charcoal?), none of the anchors could be certain of what they were seeing.

—Alessandra Stanley, “White or Black? Maybe Beige? As Smoke Detectors, the Anchors Were All Too Fallible,” The New York Times, 20 April 2005.

If ... I’m looking to create dramatic, smokey eyes, I’ll use a dark color, maybe even black, in the eye creases and along the lashes, and then shade outward in gradations of black or gray. Bedroom eyes, or dark, smokey, sexy eyes, are best achieved with pale colours on the lids and a darker colour running into the crease and along the upper and lower lashline. This makes the eyes look bigger.

—Kevyn Aucoin, The Art of Makeup (London: Prion, 1994).

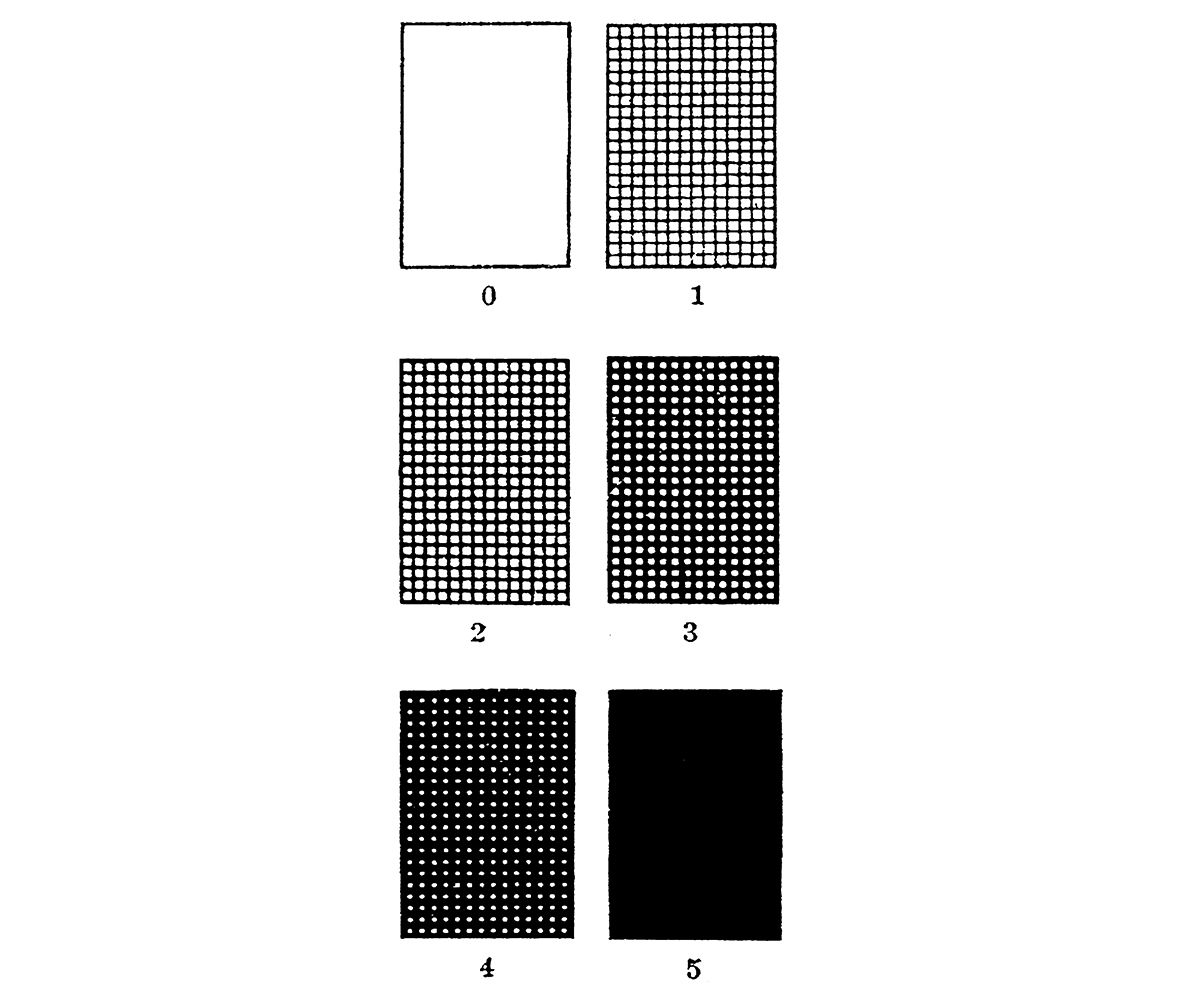

Some gardeners will go to great lengths to evict their unwelcome underground neighbours, setting traps, putting down poison and even trying to smoke them out. But with its antennae-like whiskers sensing every vibration in the earth, the mole has more tricks up its velvety sleeves than might at first be thought. To avoid smoke, it simply manoeuvers itself at right angles into the tunnel wall and uses its fat bottom as a stopper.

—Bill Mouland, “Did the Earth Move for You?,” Daily Mail Weekend, 12 April 2008.

In 1956 the British government passed the Clean Air Act, which succeeded in its goals. “We didn’t mess about with soot trading or breathing credits,” Labour MP Alan Simpson recalls. “We just told industry it had to change to smokeless fuel.” But the situation today is less tractable than in 1956, for three reasons. First, and most obviously, the problem is on a vastly greater scale. Second, neoliberal ideology places the greatest emphasis upon the least effective, even counterproductive, measures: carbon markets and individual lifestyle change. Third, whereas the British state could impose a law upon corporations in 1956, tackling global warming requires transnational regulation.

—Gareth Dale, “On the Menu or at the Table: Corporations and Climate Change,” International Socialism, vol. 2 no. 116 (Autumn 2007).

3 tbsp olive oil

3 tsp balsamic vinegar 3 tbsp granulated sugar

2 tbsp soy sauce

2 large red onions, cut into wedges

Combine the olive oil, balsamic vinegar, sugar, and soy sauce in a large bowl and blend with a wire whisk until the sugar dissolves. Add the onion wedges and toss to coat. Pour all the ingredients in a shallow 23 × 32.5-centimetre / 9 × 3-inch baking dish and place on your cooker.

Smoke-roast, stirring every 20 minutes, for 2 hours or until the onions are soft and coated with a thick glaze.

—Paul Kirk, The Smoked Food Cookbook: Revolutionary Recipes for Smoking and Barbecue Cooking (London: Apple Press, 2001).

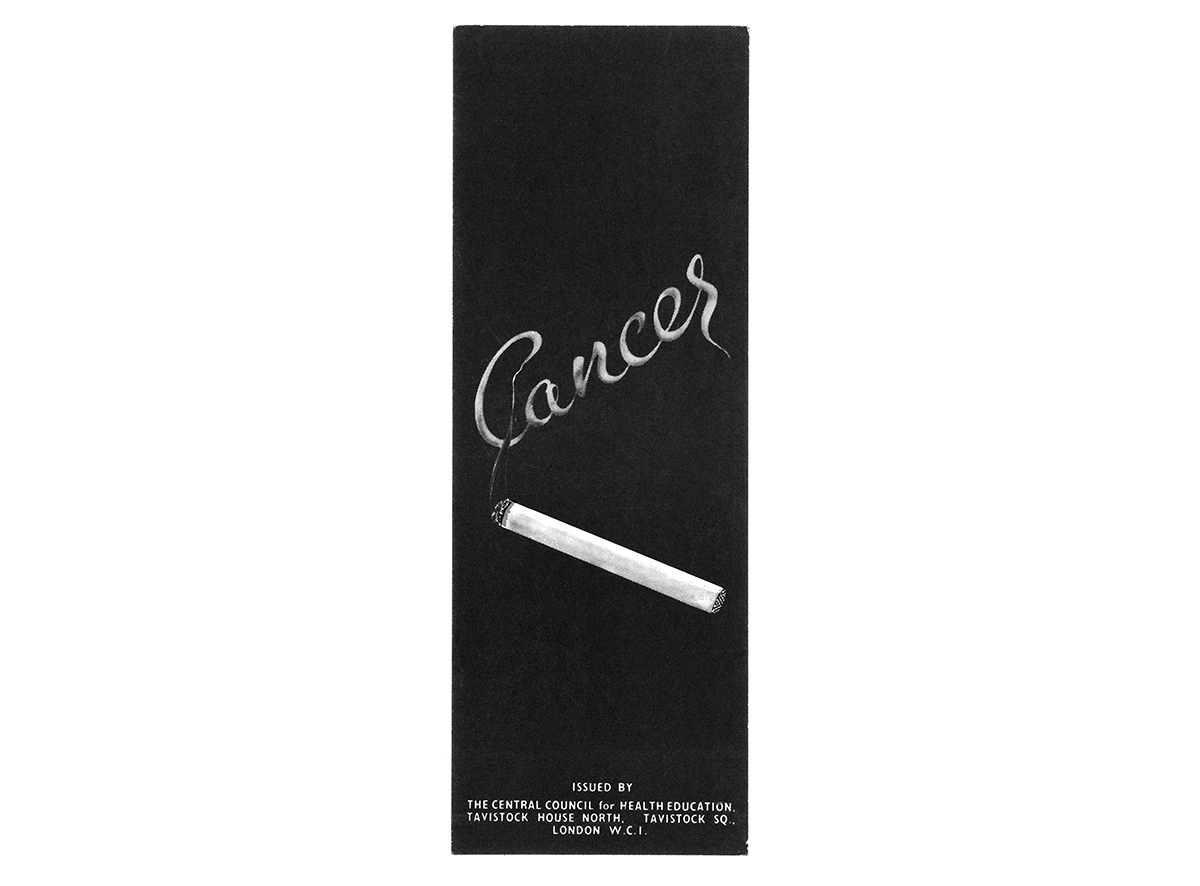

Charcoal found in Southern African caves indicate that humans have been able to use fire [for] 1.5 million years. ... Since then, the fires managed to escape from the caves and have regularly swept through vegetation all over the world. Wildfires can be started both by people and by acts of nature. Whatever the origin, people and animals die, crops and resources are destroyed, and smoke adversely affects the health of many more people outside the immediate area of wildfire. …

In developing countries, vegetation fires increase the risk of acute respiratory infections, a major killer of young children. The health of women is also adversely affected, as they are already exposed to high levels of air pollution in the home as a result of spending many hours cooking over non-vented indoor stoves. …

In 1997–98, forest fires in South-east Asia affected some 200 million people in Brunei Darussalam, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand. Massive movements of population fleeing the fires and smoke added to the emergency, while the increase in the number of emergency visits to hospitals during the crisis demonstrated its severity.

—“Vegetation Fires,” World Health Organization fact sheet no. 254, August 2000. A version is available at medbc.com/annals/review/vol_13/num_3/text/vol13n3p178.htm.

There was a kind of smoke in the air between himself and a line of hedges. It waved, billowed, and altered: a very thin smoke. He blinked his eyes, then shook his head, but it was still there.

He swallowed hastily, closed his lunch box, and slung it over his shoulder by its strap. He stood up.

He felt no fear. He was only excited—and curious.

The smoke was vaguely growing thicker, and taking on a shape. Vaguely, it looked like a cow, a smoky, insubstantial shape that could be seen through. Was it a hallucination? A creation of his mind? He had just been thinking of a cow.

Hallucination or not, he was going to investigate.

With determination, he stepped toward the shape.

—Isaac Asimov, “Hallucination,” Gold: The Final Science Fiction Collection (London: Voyager, 1996).

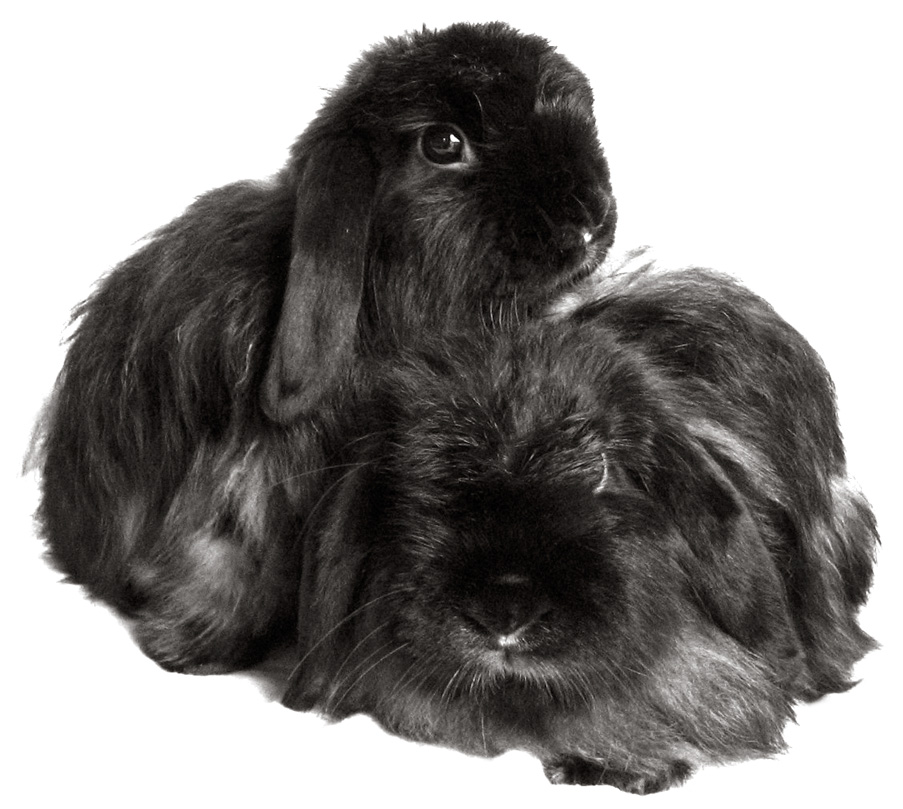

Bollywood must kick its nicotine habit. The Indian government announced this week that tobacco would be banned from the nation’s screens, leaving health campaigners sceptical, and incensing Mumbai’s powerful film industry. The law will forbid the display or use of tobacco products in films and television programmes made after August 1.

All films and television shows made before this date, including foreign ones, must either be censored with the pixellated fuzz that normally covers genitalia and bloody body parts, or flash up a “prominent” health warning at the bottom of the screen for as long as the evil weed remains in view.

Bollywood stars have warned of the threat to freedom of expression. Anupam Kher, a leading actor, says the government’s plan is “ridiculous” and will stifle creativity. “Tomorrow, the government can turn around and say: ‘Don’t show guns in movies as it will encourage violence.’”

The government took the step after a recent World Health Organisation study held Bollywood responsible for glamorising smoking. Dr. Anbumani Ramadoss, health minister, said actors had a “lasting impact on the minds of children and young adults.”...

With more than 200m tobacco users, of whom nearly 17m are under the age of 25, India is the last big emerging market still overwhelmingly ignorant of the health risks of smoking. ...

If the ban is ever enforced, which is unlikely, it will have little or no impact on the health of the millions of Indians who chew cheap tobacco rather than smoke it, do not own televisions and never come close to going to the cinema.

—Jo Johnson, “Screen Test for Indian Tobacco,” The Financial Times, 3 June 2005.

After the seventh week at sea Maskelyne began producing a nightly variety. His own contribution to the show was a makeshift version of the Aladdin story, in which he was assisted by Frank Knox, who donned a yellow mop wig to become a blonde temptress. By rubbing a ship’s lantern, Jasper conjured up a turbaned djinn floating on a cloud of white smoke. This genie offered to grant three wishes. Jasper took suggestions from his audience and, in response to the inevitable requests, materialized Knox as a ghostly pin-up girl, a turkey dinner and, most popular, a kettle that supplied an endless variety of beverages upon request.

—David Fisher, The War Magician (London: Corgi Books, 1983).

It looked just like smoke but with shapes round and squarish.

Though hard to light touch, touch it hard—it will perish!

Dioxide of silica makes just one little part of it,

But nine ninety-nine parts of air is the heart of it.

—“Ode to Aerogel,” originally published on NASA’s children’s site Space Place, undated. Available at www.utc.edu/challenger-stem-learning-center/pdfs/comet-mission-prep-with-activities.pdf [link defunct—Eds.].

This is the transcript of the recording of a meeting between President Nixon and H. R. Haldeman in the Oval Office on 23 June 1972 from 10:04 am to 11:39 am.

HALDEMAN: Okay—that’s fine. Now, on the investigation, you know, the Democratic break-in thing, we’re back to the—in the, the problem area because the FBI is not under control, because Gray doesn’t exactly know how to control them, and they have, their investigation is now leading into some productive areas, because they’ve been able to trace the money, not through the money itself, but through the bank, you know, sources—the banker himself. And, and it goes in some directions we don’t want it to go. Ah, also there have been some things, like an informant came in off the street to the FBI in Miami, who was a photographer or has a friend who is a photographer who developed some films through this guy, Barker, and the films had pictures of Democratic National Committee letterhead documents and things. So I guess, so it’s things like that that are gonna, that are filtering in. Mitchell came up with yesterday, and John Dean analyzed very carefully last night and concludes, concurs now with Mitchell’s recommendation that the only way to solve this, and we’re set up beautifully to do it, ah, in that and that ... the only network that paid any attention to it last night was NBC ... they did a massive story on the Cuban ...

NIXON: That’s right.

HALDEMAN: thing.

NIXON: Right. ...When you get in these people when you ... get these people in, say: “Look, the problem is that this will open the whole, the whole Bay of Pigs thing, and the President just feels that” ah, without going into the details ... don’t, don’t lie to them to the extent to say there is no involvement, but just say this is sort of a comedy of errors, bizarre, without getting into it, “the President believes that it is going to open the whole Bay of Pigs thing up again. And, ah, because these people are plugging for, for keeps and that they should call the FBI in and say that we wish for the country, don’t go any further into this case,” period!

—“The Smoking Gun Tape,” 23 June 1972. Transcript available at watergate.info/1972/06/23/the-smoking-gun-tape.html.

One of the leading causes of statistics.

Fletcher Knebel

—Aubrey Dillon-Malone, The Cynic’s Dictionary (London: Prion, 1999).

Explanation: Very bright in infrared light, well-known starburst galaxy M82’s popular name describes its suggestive shape seen at visible wavelengths—The Cigar Galaxy. Ironically, M82’s fantastic appearance in this Spitzer Space Telescope image really is due to cosmic “smoke”—the infrared emission of extended dust features blown by stellar winds from M82’s luminous, central star forming regions. The false-color view highlights a component of dust emission from complex carbon molecules called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons or PAHs. PAHs are also seen in star forming regions throughout our own, much calmer, Milky Way Galaxy and are products of combustion on planet Earth. Likely triggered by interactions with nearby galaxy M81, M82’s intense star formation activity appears to be blowing out immense clouds of dust and PAHs extending nearly 20,000 light-years both above and below the galactic plane. M82 is about 12 million light- years away in the constellation Ursa Major.

—Chris Engelbracht et al., “Astronomy Picture of the Day,” nasa.gov, 14 April 2006. Available at apod.nasa.gov/apod/ap060414.html.

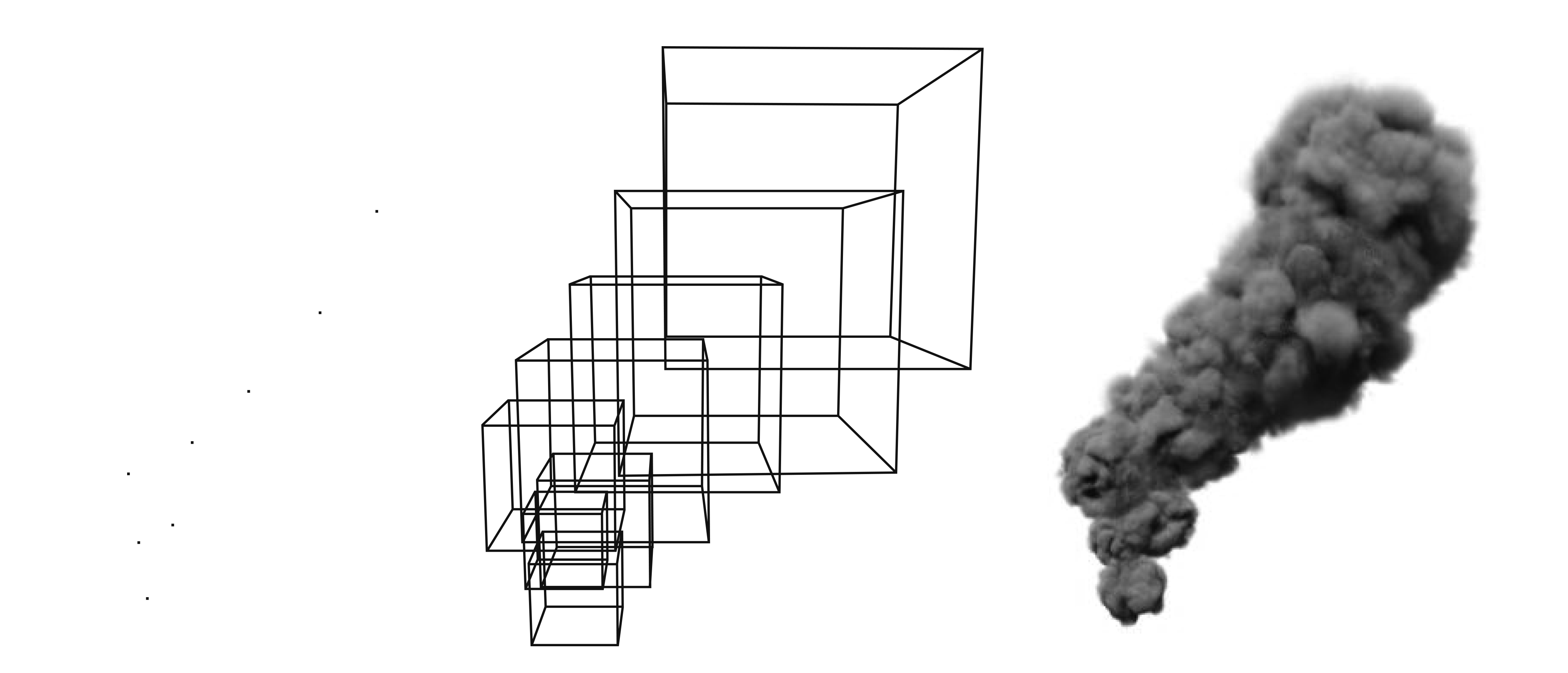

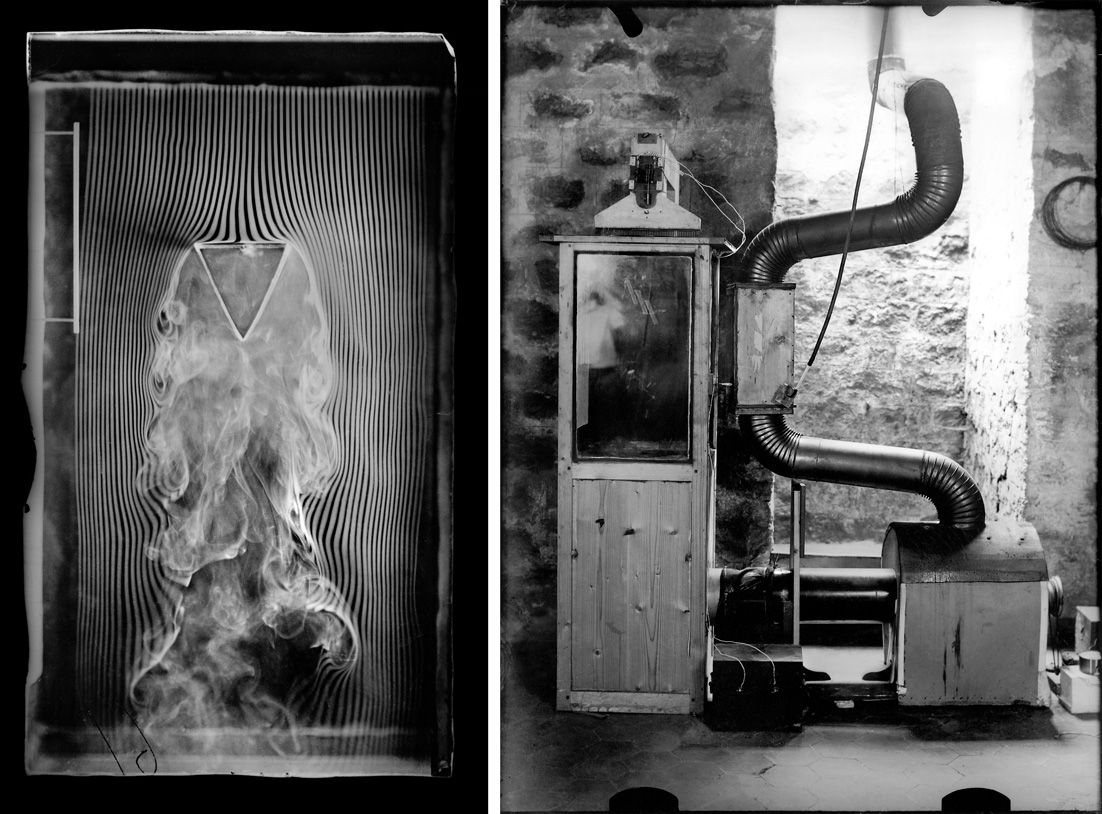

The modeling of smoke and other gaseous phenomena has received a lot of attention from the computer graphics community over the last two decades. Early models focused on a particular phenomenon and animated the smoke’s density directly without modeling its velocity. Additional detail was added using solid textures whose parameters were animated over time. Subsequently, random velocity fields based on a Kolmogoroff spectrum were used to model the complex motion characteristic of smoke. A common trait shared by all of these early models is that they lack any dynamical feedback. Creating a convincing dynamic smoke simulation is a time-consuming task if left to the animator.

A more natural way to model the motion of smoke is to simulate the equations of fluid dynamics directly. Kajiya and Von Herzen were the first in CG to do this. Unfortunately, the computer power available at the time (1984) only allowed them to produce results on very coarse grids. Except for some models specific to two dimensions, no progress was made in this direction until the work of Foster and Metaxas. Their simulations used relatively coarse grids but produced nice swirling smoke motions in three dimensions. Because their model uses an explicit integration scheme, their simulations are only stable if the time step chosen is small enough. This makes their simulations relatively slow, especially when the fluid velocity is large anywhere in the domain of interest. To alleviate this problem, Stam introduced a model which is unconditionally stable and consequently could be run at any speed. This was achieved using a combination of a semi-Lagrangian advection schemes and implicit solvers. Because a first-order integration scheme was used, the simulations suffered from too much numerical dissipation. Although the overall motion looks fluid-like, small-scale vortices typical of smoke vanish too rapidly.

—Ronald Fedkiw, Jos Stam, and Henrik Wann Jensen, “Visual Simulation of Smoke,” SIGGRAPH '01: Proceedings of the 28th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques (New York: Association for Computing, 2001). Available at www.graphics.stanford.edu/papers/smoke.

Here we can see the steps involved in combining particles and hypertextures. On the left is the basic particle system, which needs to contain only a few points. Each point will determine the movement of the entirety of smoke parented to it. The middle image shows the bounding boxes of the hypertextures, which are parented to the particles. On the right is the final image where the hypertextures have been raymarched with selfshadowing.

The result is very convincing, due to the volumetric nature of the smoke. This means that the intersecting volumes of different hypertextures will interface in a visually correct manner.

—David Stopford, “Representing Smoke in Computer Graphics,” National Centre for Computer Animation, Bournemouth University, undated.

Commonly at powwows and other public events, sage, sweet grass and/or cedar are burned to purify one’s self, one’s space, and one’s spiritual or healing tools. After lighting the smudge, we offer it to the cardinal directions, or hold it near our hearts. We wash or fan the smoke over our bodies by first bringing it towards the heart, then inhaling, pulling it up over the head, washing it down the arms, etc.

We also burn herbs during healing work and prayer. This helps one to connect to one’s higher power. The smoke carries one’s intention to the Sky World, where the Spirit Beings and our ancestors live.

During healing work, the smoke may be directed over the patient by blowing, or fanning either with the hand or with feathers. This clears out old unhealthy energy and brings in the special attributes of the herbs.

—Harvest McCampbell, Sacred Smoke: The Ancient Art of Smudging for Modern Times (Summertown, TN: Native Voices Books, 2002).

The Pythagorean Hippasus and his disciple Heraclitus (ca. 540–475 B.C.) believed that fire was the ultimate matter from which everything else could be obtained or into which it could finally be resolved. Combustion to them therefore was simply the resolution of a body into its elementary form, and this idea that during combustion something complex turns into something of more simple constitution, was to persist right through to the time of the Phlogiston Theory. Later, Empedocles (ca. 465 B.C.) originated the doctrine of four essential elements—earth, air, fire, and water, which was extended and developed by Aristotle (384–322 B.C.) into a complete philosophy of nature that dominated the world of science up to the time of Lavoisier. To an Aristotelian, combustion was explained on the four element theory something in this way: Any vapour given off is its air escaping, any moisture its water, any flame its fire, and any residue its earth. According to Empedocles, for example, when wood burns the smoke given off is its air, the visible flame is its fire, the exuded moisture is its water, and the ash left behind is its earth: in other words the resolution of a complex body into its components.

—J. H. White, The History of the Phlogiston Theory (London: Edward Arnold, 1932).

Where a Chimney smokes only when a fire is first lighted, it may be guarded against by allowing the fire to kindle gradually, or by heating the chimney by burning straw or paper in the grate previous to laying in the fire.

—[Robert Kemp Philp], Enquire Within Upon Everything (London: Houlston & Sons, 1886).

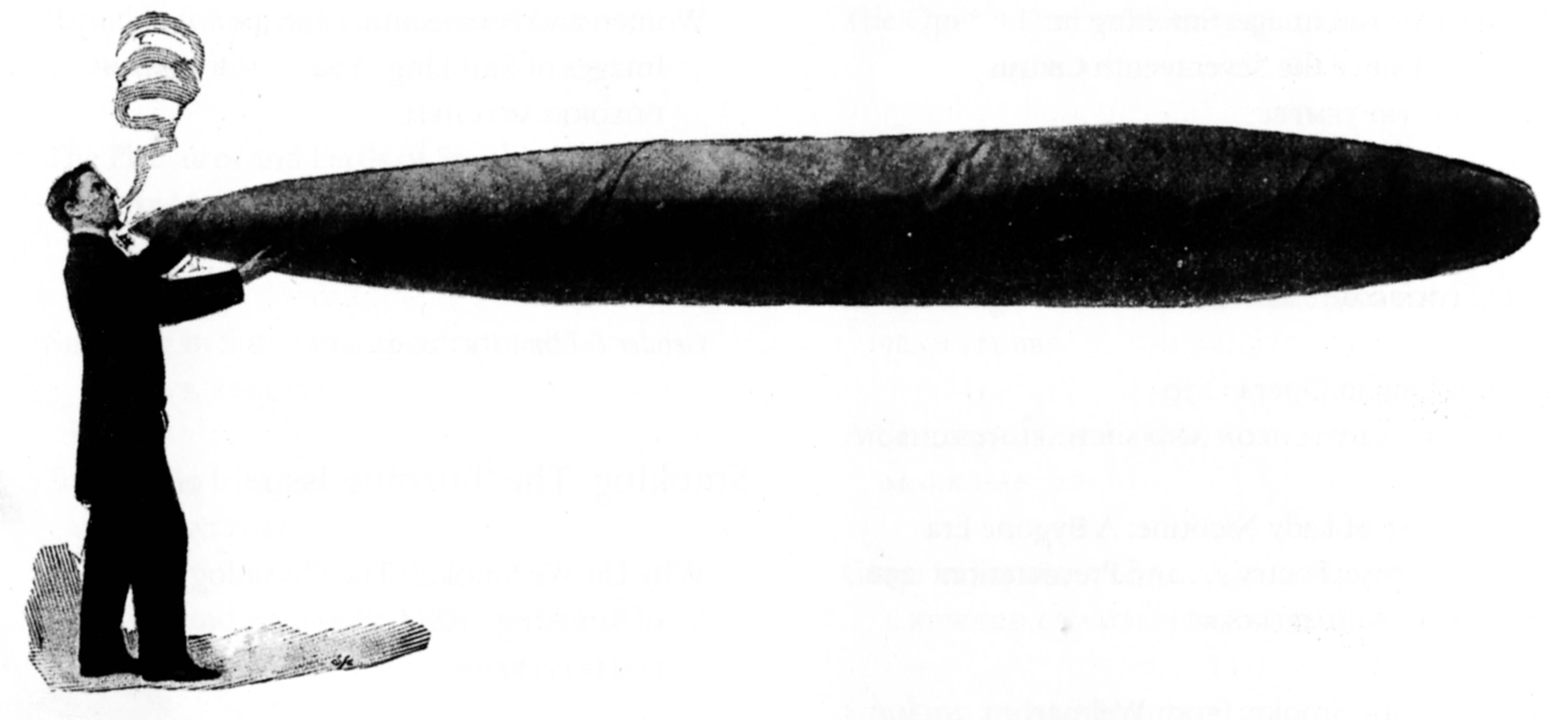

PAUL: I suppose it all goes back to Queen Elizabeth.

AUGGIE: The Queen of England?

PAUL: Not Elizabeth the Second, Elizabeth the First. (Pause.) Did you ever hear of Sir Walter Raleigh?

TOMMY: Sure. He’s the guy who threw his cloak down over the puddle.

PAUL: That’s the man. Well, Raleigh was the person who introduced tobacco in England, and since he was a favorite of the Queen’s—Queen Bess, he used to call her—smoking caught on as a fashion at court. I’m sure Old Bess must have shared a stogie or two with Sir Walter. Once, he made a bet with her that he could measure the weight of smoke.

DENNIS: You mean, weigh smoke?

PAUL: Exactly. Weigh smoke.

TOMMY: You can’t do that. It’s like weighing air.

PAUL: I admit it’s strange. Almost like weighing someone’s soul. But Sir Walter was a clever guy. First, he took an unsmoked cigar and put it on a balance and weighed it. Then he lit up and smoked the cigar, carefully tapping the ashes into the balance pan. When he was finished, he put the butt into the pan along with the ashes and weighed what was there. Then he subtracted that number from the original weight of the unsmoked cigar. The difference was the weight of the smoke.

TOMMY: Not bad. That’s the kind of guy we need to take over the Mets.

—Dialogue from Smoke, 1995, written by Paul Auster and directed by Wayne Wang.

In the other gardens

And all up the vale,

From the autumn bonfires

See the smoke trail!

Pleasant summer over

And all the summer flowers,

The red fire blazes,

The grey smoke towers.

Sing a song of seasons!

Something bright in all!

Flowers in the summer,

Fires in the fall!

—Robert Louis Stevenson, “Autumn Fires,” A Child’s Garden of Verses (London: Longmans, 1885).

Recently, anti-smoking groups have also had some early successes at eroding the social acceptability of smoking. ... We [at the Phillip Morris tobacco company] must use every creative means at our disposal to reverse this destructive trend. I do feel heartened at the increasing number of occasions when I go to a movie and see a pack of cigarettes in the hands of a leading lady. This is in sharp contrast to the state of affairs just a few years ago when cigarettes rarely showed up in cinema. We must continue to exploit new opportunities to get cigarettes on screen and into the hands of smokers.

—Draft marketing meeting speech for Hamish Maxwell, president of Phillip Morris International, 24 June 1983. Available at industrydocuments.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/#id=mtbk0111.

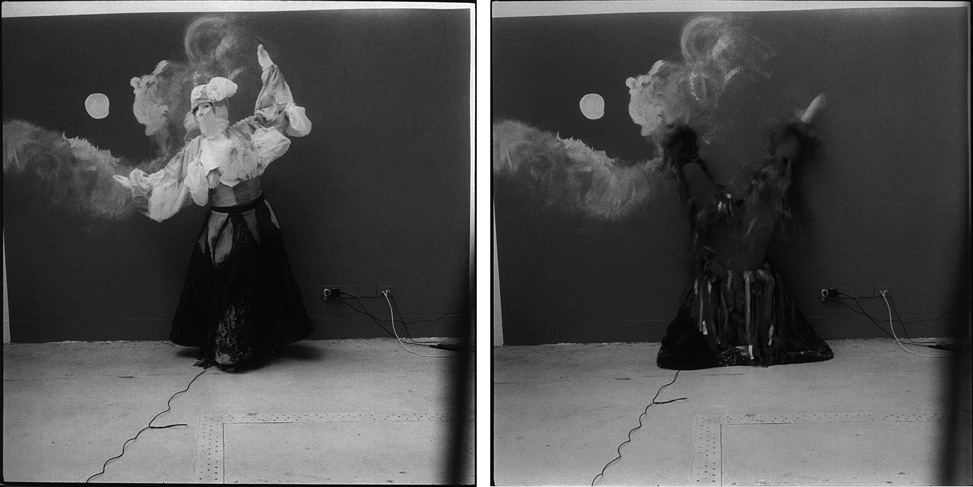

While I was the Helen Chadwick Arts Council of England Fellow at the British School at Rome, I made a series of studio photographs and a performance in a costume designed to resemble an erupting volcano. Interested in the erotic status of Vesuvius (one of the final destinations of The Grand Tour, the precursor of tourism), I commissioned an erupting volcano costume. Designed to invert: while I stand upright the top of the garment represents superheated gas and ash billowing from the cone of a volcano. As I do a headstand, I reveal red tights and flamed underskirts that resemble lava flow.

Bees are apt to be bad-tempered if there is robbing going on, or if queenless, or during a death, and after removal of harvest, and can be made bad-tempered at other times unless quietly handled and with consideration. Avoid all sudden movements and anything that jars the combs, and of course avoid crushing the bees. The bees over a fortnight old are the more disposed to be troublesome, and when they are out flying in the middle of the day the hive may be examined with greater ease, but an extensive examination during a honey flow may so disorganize the labours of the hive as to result in a dead loss of 5 lb. or more of nectar. The operator should stand behind or beside the hive and never in the line of flight.

When using the smoker, put in a puff or two of smoke at the entrance and wait a minute or two (not a moment or two, but 60 to 120 seconds) for it to take effect before opening the top of the hive; then use a little smoke at the top, the less the better. If bees in a normal condition do not answer readily to a little smoke and deliberate handling they should be re-queened.

—E. B. Wedmore, A Manual of Beekeeping for English-Speaking Beekeepers (London: Edward Arnold, 1932).

If smoking is so bad for you how come it cures herring?

—Traditional

Smoke, when no wind is present, moves steadily upward in a column, usually widening as it grows further from the flame. ... Starting off with a basic cone shape, you just build and stack semi-circles with varying sizes and you’ve got yourself a simplified version of smoke. If you would like to make a more realistic smoke stack, just as you would detail a tree, just add multiple short lines and straight lines to add the wispy look of smoke. ...

When there is a gust of wind, smoke will become engulfed and curl up in itself to form a sort of mushroom-like effect. This can also be used to display a tremendous explosion, but make sure to straighten out the “wind” lines and push the smoke up to become flatter.

—Rio, “Smoke and Explosions,” undated. Available at www.resoo.org/www/bd/manga/tut/smoke.htm.

MAGIC SMOKE: n.

A substance trapped inside IC packages that enables them to function (also called blue smoke; this is similar to the archaic phlogiston hypothesis about combustion). Its existence is demonstrated by what happens when a chip burns up—the magic smoke gets let out, so it doesn’t work anymore. ...

[A “USENETter”] tells the following story: “Once, while hacking on a dedicated Z80 system, I was testing code by blowing EPROMs and plugging them in the system, then seeing what happened. One time, I plugged one in backwards. I only discovered that after I realized that Intel didn’t put power-on lights under the quartz windows on the tops of their EPROMs—the die was glowing white-hot. Amazingly, the EPROM worked fine after I erased it, filled it full of zeros, then erased it again. For all I know, it’s still in service. Of course, this is because the magic smoke didn’t get let out.”

—From the compendium of hacker slang The Jargon File, undated. Available at catb.org/jargon/html/M/magic-smoke.html.

The belief that analysis by fire would duplicate the separation obtained by a slow natural putrefaction was widespread. ... [In] his theoretical introduction to the Basilica chymica, Oswald Crollius insisted that visible experiments by the spagyrists provided indisputable evidence that natural bodies could not be divided into more than three substances, “mercury or liquor, sulphur or oil, and salt.” Both Behuin and Crollius pointed to the example of the burning twig: here the smoke indicated the presence of mercury, the flame, sulphur, and the ash, salt. This was little comfort to the Aristotelians, who had traditionally utilized the same example to show the four elements: earth (ash), water (sap), air (smoke), and fire (visible in burning).

—Allen G. Debus, The Chemical Philosophy: Paracelsian Science and Medicine in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 1977).

[According to Eugene Pelletan in the 1860s, in] the sixteenth century the monsoon wafted to Manilla a vessel manned by apes of a singular species. Dressed up like men, they imitated human shape so well as to cause an illusion for the first few moments. But they ate fire-sticks, and ejected the smoke through a nasal protuberance of portentous length.

These curious animals were Spaniards, who had just learnt in America the art of smoking, and brought it piping hot to the coast of Asia. The inhabitants of the Indian Archipelago, accustomed to the small noses of the Mayan race, could not behold without secret horror the cornucopious aquiline of the Castilian type. The long noses got the upper hand of the short noses, thanks to the help of the arquebuse. The conquerors tamed the conquered race, reducing them to slavery. Do you know how? By stupefying and besotting them with cigars.

—[n.a.], An Arm-Chair in the Smoking-Room: Or, Fiction, Anecdote, Humour and Fancy for Dreamy Half-Hours (London: Stanley Rivers, 1870).

Implicasphere is an occasional publication. Past editions include “String,” “Mice,” “Folly,” “The Nose,” “Salt & Pepper,” “Stripes,” and “The Onion.”

For orders and information, and to give feedback, email info@implicasphere.org.uk or visit www.implicasphere.org.uk [link defunct—Eds.].

Texts have been reproduced as they appear in the original publications. Idiosyncrasies and house styles have been largely left intact. Considerable effort has been made to trace and contact copyright holders and to secure replies before publication, but this has not been possible in all instances, particularly with old material. We apologize for any inadvertent errors or omissions. If notified, the editors will endeavor to correct these at the earliest opportunity.

“String,” “Mice,” and “Folly” were commissioned by PEER and designed by Adam Hooper. All other issues are designed by Fraser Muggeridge. “The Nose” and “Salt & Pepper” were supported by the Moose Foundation for the Arts and the Elephant Trust. “Stripes” and “The Onion” were supported by the Henry Moore Foundation and the National Lottery through Arts Council England, London.

Implicasphere is edited by Cathy Haynes and Sally O’Reilly.

“Smoke” is supported by the National Lottery through Arts Council England, London. The editors are also grateful to Cabinet, New York, and the Pump House Gallery, London. Implicasphere’s exhibition “Smoke” is at the Pump House Gallery, London, from 8 October to 14 December 2008.

Designed by Fraser Muggeridge studio.

Printed in an edition of 13,000 on Cyclus Offset (recycled).

© Implicasphere Ltd, London, 2008 Registered company no. 5757303.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.