The Broken Circuit: An Interview with Lauren Berlant

The political economy of shame

Sina Najafi, David Serlin, and Lauren Berlant

According to psychologist Silvan Tomkins, the child experiences shame when the object of desire, for example the mother, does not reciprocate and breaks the circuit of attachment. This leads to an emotional disorientation in which the child internalizes disconnection, thus creating the conditions for embarrassment and self-loathing. Many cultural theorists have adopted the notion of the “broken circuit” as a way of examining how specific social relations could shame members of marginalized groups and determine their experience as shamed subjects. But does the breaking of the circuit—some form of emotional disconnection—necessarily lead to self-loathing?

Lauren Berlant, the George M. Pullman Professor of English at the University of Chicago, has written extensively about the relationship between affective investments, practices of sociability, and questions of citizenship and community. For her, the self-loathing that we typically associate with the concept of shame is only one of many possible outcomes of the “broken circuit.” Sina Najafi and David Serlin spoke with Berlant by phone in July 2008.

Cabinet: When did contemporary cultural criticism begin grappling with the category of shame?

Lauren Berlant: In terms of charting a contemporary genealogy (i.e., one that doesn’t look to Erving Goffman’s Stigma (1963) or the modernist ethnographic convention of nominating shame and guilt cultures), we might begin with Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s Epistemology of the Closet, published in 1990, which asked questions about the relationship between socially marginalized identity categories and modes of psychological or affective subjectivity. In Sedgwick’s rephrasing of margin-center relations, populations that were associated with non-normative modes of life—in this case, queer and non-normative sexualities—were deemed to be shamed populations. I want to say something precise about what her revisionary operation entailed. What Sedgwick was saying was that a structural social relation—enacted by stipulated and administrative laws and norms—was shaming. She was adapting an affective language to a political analysis. At the same time, the shame of being deemed a member of that population was said to produce a shamed subjectivity, which meant a subjectivity that felt a lot of shame.

This particular arc of thinking about shame is probably related to St. Augustine’s claim that sexuality is at the center of the subject, that sexuality is definitively shameful, and that shamed sexualities produce shamed subjects who then have to negotiate life from a perspective of already being fallen and unworthy. Foucault criticized the model of sexuality that posits it as the subject’s truth, of course. As for Sedgwick, I think that this spreading mimeticism around shame (oppression works through shaming, and produces subjects organized by shame) is a very controversial claim about persons. At the time her ideas were first circulating, it was not deemed controversial but incredibly emancipatory, because they proposed an affective structure for a political relation. It explained how it would be possible to think of the structural subordination of a population in terms of an emotional map of the very identities of the people who were being named by it.

I wouldn’t want to misrecognize the interest in shame as only coming from Epistemology of the Closet, however. There was also a lot of feminist work on interrupting sexuality as the site for the reproduction of gendered shame that is never acknowledged enough. Angela Davis, Gloria Anzaldúa, Shulamith Firestone, and Pat Califia, for example, had long been busy trying to invent ways of thinking about how sexual shame is actually a powerful register for trying to understand what it means to be identified, or not identified, with the normativity of a nation. Yet it was also incredibly dramatic for Sedgwick—and Judith Butler, too, but Sedgwick especially—to make a claim that what looks like a political structure is fundamentally an affective structure that forms our subjectivity. I don’t think it can be overestimated how big that shift was, but it was also a shift that came out of a long discussion.

How does Sedgwick’s work fit within explorations of shame by psychology?

In the mid-1990s, Sedgwick and Adam Frank recovered the work of psychologist Silvan Tomkins (1911–1991) and reintroduced it for scholars interested in the concept of shame. Following Tomkins’s work, Sedgwick and Frank describe the experience of shame structurally as the experience of a “broken circuit” of attachment and desire that ought to circulate between the subject and its treasured object. (Their presumption, I think, is that one can make demands for reciprocity on both persons and worlds.) So if somebody has a form of longing that gets attached to a person or world, the moment of shame is when the person/world breaks its relation of reciprocity with the subject. For Tomkins, shame occurs when a child experiences the refusal of their attachment. When the child looks away because it feels that it’s been refused or rejected by its mother, that is the exemplary moment of shame.

In my own work, I argue that the feeling of the world withdrawing from you and therefore throwing you back on yourself could be described as shame, but that says nothing about the experience of it. The broken circuit could also involve anger, numbness, hunger, a desire to self-stimulate, a compulsion to repeat, the pleasure of a recognition, grief, and/or curiosity, and these wouldn’t merely be defenses against the impact of the pure feeling of shame, but actually different responses to being affectively cut off.

Although the structure of shame for Sedgwick and for Tomkins isn’t necessarily aligned with the experience of shame, much work by scholars using shame as an analytical category assumes that the structure and the experience of shame are always aligned, that the broken circuit would be felt as shame, a shame we would recognize as the conventional emotion. But this is a mistake, and I think it occurs because the language of emotion often produces a sense of generality and transparency that enables things that aren’t very like each other to seem as if they are. So, let’s ask again: what does it mean to shame X? Is de-shaming X the same thing as de-repressing it? If I used to be ashamed of my queerness and had to produce defenses around that shame, does delaminating shame from my queerness also emancipate my sexuality? Is that emancipation the same thing as being shameless? Is de-shaming queerness the same thing as having pride? (This is what the Gay Shame movement is always asking.) My point is that I want our discussions of affect and emotion not to presume their clarity, coherence, or intensity of drama, nor to see them as grounding the subject for better or worse in an identity or a social population. The leveling effect of biopower (everyone in the shamed population is alike defined by the shaming quality) is not lived a priori coherently or homogeneously. But that’s an empirical question.

For you, is this incoherence productive or counter-productive?

What’s not productive is when people aspire to an explanation of a social relation through the fantasy that the emotional event tells a simple, clear, visceral truth about something. One way my claims revise Foucault’s is that I think emotions, and not sexuality, are what took up the place as the “truth” of the modern subject. What we understand as sexuality was one among many scenes of installing conventionality in the people who were defined according to projections about their capacity to manage appetites and affects. So if I say I’m a “shamed subject,” that represents me as someone who is grounded by my own emotional self-understanding. On the other hand, this concept of myself as affectively simple makes me seem more open to change. If only! Also, if my shame is to represent injustice, then my lack of shame should represent justice—and you know that’s not true, because shamelessness can be a bullying mechanism or a defense too.

Negative political feelings provide important openings for measuring injustice but their presence or absence isn’t really evidence of anything. I might be a bourgeois who thinks that the world owes people like me who work hard an unprecarious life that will add up to something, too, but then my sense of injury isn’t objectively a measure of injustice. It’s a measure of wounded privilege. This is why I work against the idea that emotions actually ground you somewhere in true justiceland. Emotion doesn’t produce clarity but destabilizes you, messes you up, and makes you epistemologically incoherent—you don’t know what you think, you think a lot of different kinds of things, you feel a lot of different kinds of things, and you make the sense of it all that you can. The pressure on emotion to reveal truth produces all sorts of misrecognition of what one’s own motives are, and the world’s. People feel relations of identification and revenge that they don’t admire, and attachments and aversions to things that they wouldn’t necessarily want people to know that they have.

It’s part of my queer optimism to say that people are affectively and emotionally incoherent. This suggests that we can produce new ways of imagining what it means to be attached and to build lives and worlds from what there already is—a heap of conventionally prioritized but incoherent affective concepts of the world that we carry around. We are just at the beginning of understanding emotion politically.

In your article “Unfeeling Kerry,” you discuss how John Kerry lost the 2004 election in part because of his shame over and subsequent disavowal of a certain part of his own life, namely his post-Vietnam protests against the war, which he imagined rejected his previous patriotic behavior as a soldier in Vietnam. You argue that the electorate was not comfortable with the lack of unity in Kerry evidenced by this shameful disavowal.

That essay argues that one of the things that people are purchasing when they decide to go with their “gut feelings” about a candidate—a phrase about affective discernment that has wide currency now from Malcom Gladwell and Stephen Colbert to Gerd Gigerenzer and George Lakoff—is some sense of whether the candidate is affectively intelligible to them at all. So what Bush represented—it was totally fictive, but he’s a good actor—was a coherent masculinity at ease with itself, whereas Kerry represented an incredible disavowal of the magnificent performance of sovereignty and freedom from the need to be respected that he manifested at the end of the Vietnam War. As a candidate he had to pretend that he had just been a good soldier all along. Maybe he was a good soldier all along, but that wasn’t the point. The reason that he was worthy of respect wasn’t that he was a good soldier; it was that he used the knowledge that he gained in Vietnam actually to break with the system.

He was what Foucault might call a specific intellectual.

Exactly. And when the system tells you it doesn’t respect you, you owe nothing to it and can make yourself free. That sounds kind of hokey, but it’s an important lesson about possible responses to the broken circuit other than trying to reason with it, convince it, be a good teacher of it, re-seduce it, or be pragmatic in a depressive collaboration. Anyway, Kerry was proud of his freedom after the war, and then during his presidential run he had to pretend that all along he was conventionally patriotic, when actually he had been interfering with the terms of the reproduction of patriotism itself.

We are interested in pursuing shamelessness. Are you?

Not so much, because I am in the middle of working through an almost antithetical theoretical problem about sensing the historical present. It’s a kind of proprioceptive history about the present as a relatively affectively formless space: this project articulates models of affect management (anxious attachment disorder and the like) with Lacanian conceptions of fantasy that see life as a comedy of misrecognition and the Deleuzian project of fomenting potentiality as the subject’s undoing. In contrast, shamelessness is structured as a moment of clarity within normative frames. But for you, I’m game!

You may be asking about shamelessness as a political end and as a political tactic. These are two different things. As a political end, I want the end of erotophobia, the fear of sexuality as such that produces so much shaming pedagogy around it. As a political tactic, shamelessness is the performative act of refusing the foreclosure on action that a shamer tries to induce. Stop masturbating, you idiot! But if I act shamelessly, I also might be daring you to shame me again, and come to love the encounter with shame. This shapes the hyperbolic spaces of outraged shamelessness in the right-wing media. Bring shame on, they say, we’re shameless; so give us your best shot!

Shamelessness as political tactic might also perform freedom in the way I described before, the freedom to give up getting legitimacy in normal terms. This may be what people respond to in Barack Obama: there are things that he feels strongly about that he’s not interested in justifying to anyone. Obama’s claim is a pretty sentimental, practically contentless formal claim about “America” as the name for the possibility of a social world, not one made of individuals but one that’s fundamentally collective, interdependent, and politically self-organized. He uses civil society language to say that people should understand themselves and act fundamentally as members of a public. He’s claiming that to commit to the process of an active debate within a field of solidarity is what’s best about politics, and that the idiom of policy is practically another scene altogether. So he doesn’t care so much when people don’t like his particular political decisions. He’s more invested in the process of fomenting publics that desire the political. It’s a pretty shameless strategy, in the sense that he is refusing the normative ideological contracts that have shaped mainstream politics over the last 40 years.

Could one identify shamelessness, then, as an affect of neo-liberalism?

No, I wouldn’t go there at all. I mean, think about civil rights actions. Look at, for example, the class/biopolitics of the distribution of composure. Whose forms of self-regulation get legitimated, whose forms of self-regulation are ways of going under the radar, and whose forms of self-regulation are in-your-face messages? For example, you go and sit at a lunch counter where you’re not allowed and you refuse to act as though you shouldn’t be there. And it freaks everybody out because you’re not having the affect that they need you to have in order for them to be outraged by it. So I think that shamelessness doesn’t always have to be exuberant or confrontational. It can be a form of the performance of composure in places where people don’t expect it.

We often think of shamelessness in its most outrageous manifestation.

That’s the problem in working on emotion—people always imagine it hyperbolically and melodramatically. The structure of shamelessness doesn’t necessarily involve in-your-faceness. It can involve any frank refusal to produce the affect for you that you need someone to have in order for you to feel in control of the situation of exchange. It is to take control over the making and breaking of the terms in which reciprocity will proceed, if at all. But it doesn’t have to be big. What often happens when you refuse to provide affective security for people is that they fall apart, get anxious, and start acting out, often not knowing why. The affective event of performative shamelessness initiates, therefore, the potential for unraveling normative defenses. On the other hand, people often thrash around like monsters in that situation, not having skills for maintaining composure amidst the deflation of their fantasy about how their world is organized. Take the whole question of academic gentility, for example. How does the fear of being shamed, exposed, or losing face foreclose potentiality (resistance, creativity) in any kind of workplace, and what is the relation between public and cloaked forms of control? Collaborative institutions are like big reality shows, theatres of emotional performance in the guise of something else.

Speaking of which, what role do you think reality TV programs play in making visible the culture of shame?

In my work, sentimentality operates when emotions communicate authenticity that enables identification and solidarity among strangers. It doesn’t only mean that if I cry on screen you feel sad; it also means that if I’m exuberant on screen, you feel exuberant, too, or if someone humiliates me on screen, you might not only feel schadenfreude, but you might also take pleasure in my survival. When I talk in general about sentimental culture, it’s a scene of emotional transmission that reveals the affective intensities of the everyday by showing what’s overwhelming and providing a gratifyingly simplified distillation of experience. So in that regard, reality TV is an extension of sentimental culture rather than its opposite. We’re used to thinking that sentimentality is about the risk of sociality and the need to survive suffering, but narratives about this can take place in many idioms—comedy, irony, romance, satire, and other genres of intensity with a pedagogical edge.

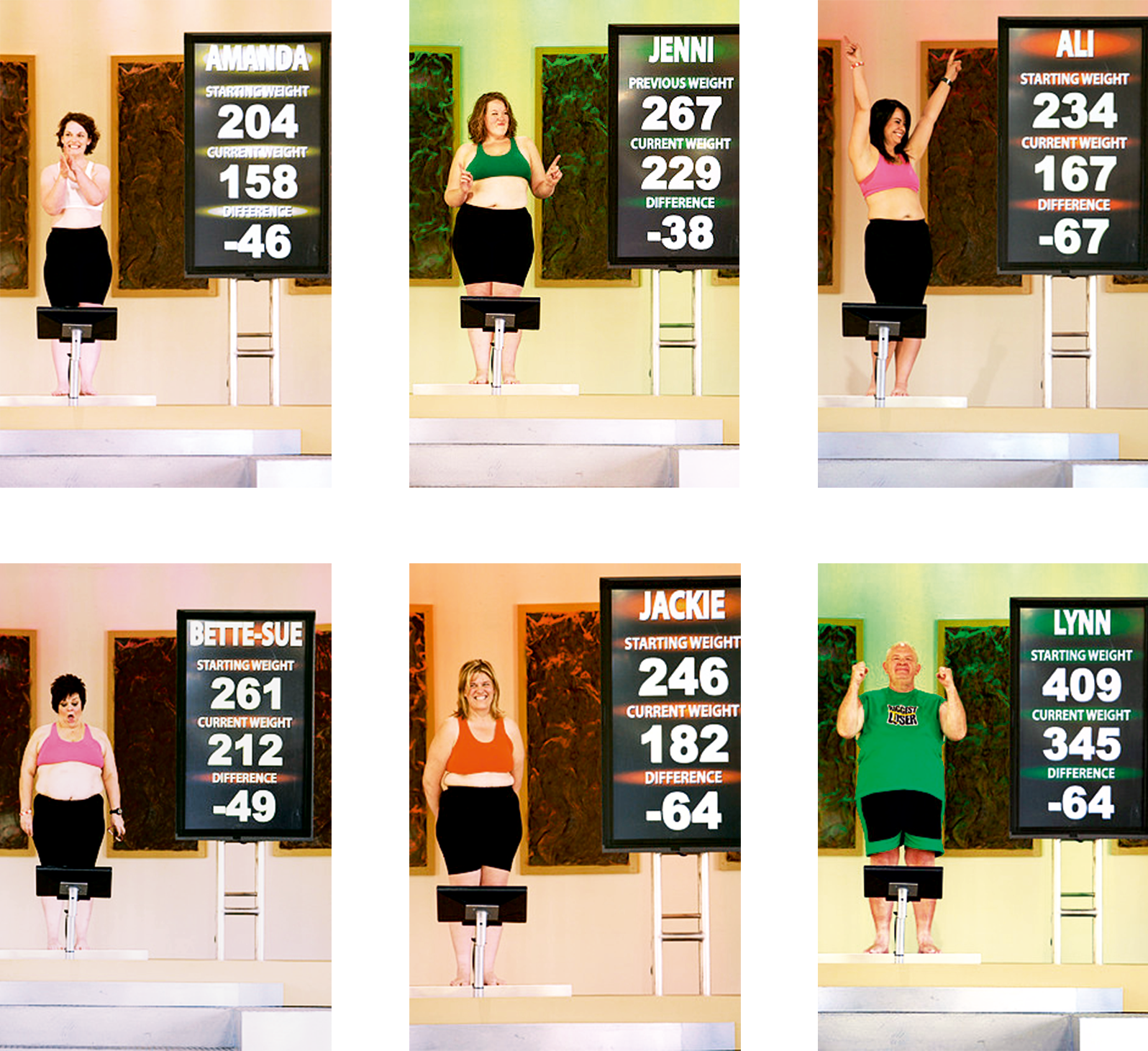

I don’t watch a lot of reality TV, but I have seen something recently that interested me—The Biggest Loser, which I had a student working on so I had to watch, and I wept while watching it, because people are so shockingly naked on it. This show is the only place in America where you get to be a loser and it’s a good thing. In a larger sense, it’s about managing people’s feelings of loss everywhere. But this show is also about a culture of shamed appetites, and in that sense it’s also about contemporary sexuality.

With shows like Survivor, you have the other problem of getting voted off if you’re too good at the game, so it’s also about strategies of mediocrity, about staying below the radar. That’s also really interesting. On The Biggest Loser, people actually cry when they vote a friend off because he or she was too good at the game. Therefore reality TV is not only about dramas of humiliation and victory, but about other forms of networking and collegiality in which you don’t try to be extra great—you just try to be competent so you’re perceived as reliable.

Being normal is a nervous place, because you can never finish performing your relation to it; on the other hand, being comfortable is also another way of thinking about what normativity provides, because if you can pass as normal then you can scoot under the radar. The whole question of how you lubricate the social never stops being difficult, and it never stops being a matter of shame, because when one confronts one’s ambivalence and incoherence one feels in a bad faith relation to the model of ethical solidity we expect from ourselves. But what if we just trained ourselves to accept that all of us are incoherent, subject to a variety of aversive and connective impulses that we are always managing? The social then would be a totally different space of intimacy and anxiety.

Lauren Berlant teaches English at the University of Chicago. Recent work related to affect, politics, and aesthetics includes The Queen of America Goes to Washington City (Duke University Press, 1997), The Female Complaint (Duke University Press, 2008), and, as contributor and editor, Intimacy (University of Chicago Press, 2000), Compassion (Routledge, 2004), and On the Case, a special issue of Critical Inquiry (2007). Her book, Cruel Optimism, is forthcoming. She can also be found at supervalentthought.wordpress.com.

Sina Najafi is editor-in-chief of Cabinet.

David Serlin is associate professor of communication and science studies at the University of California, San Diego, and an editor-at-large for Cabinet. He is the author of Replaceable You: Engineering the Body in Postwar America (University of Chicago Press, 2004).

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.