Shamefaced: An Interview with Paul Ekman

The anatomy of an emotion

Christopher Turner and Paul Ekman

Thirty years ago, Paul Ekman, who runs the Human Interaction Lab at the University of California, San Francisco, co-published the Facial Action Coding System (1978), a 500-page catalogue of 3,000 “meaningful” facial expressions that is used by organizations as varied as Pixar and the CIA. Ekman is the world authority on facial expression, about which he has since written numerous books, including The Nature of Emotion (1994), What the Face Reveals (1997), Face of Man (1980), Telling Lies (1985), and Emotions Revealed (2003). He is currently working to help the Department of Homeland Security identify “expressions of immediate deadly intent” with CCTV systems, and, before he met with Cabinet in New York, he had just spent a week in Washington DC coaching government employees in the subtleties of the human face. The seventy-four-year-old psychologist sat down to talk with Christopher Turner about shame, blushing, lie-detection, his research in the jungles of Papua New Guinea, and his work as a counter-terrorist consultant.

Cabinet: How and when did you come to study facial expression?

Paul Ekman: In the mid-1960s, the Defense Department, of all things, got caught doing research that it shouldn’t have been doing, and it had to get rid of a lot of money quickly. By accident, I bumped into the guy with the job of distributing it, and he awarded me a grant. He was married to a woman from Thailand and thought that the problems in their marriage had to do with her misunderstanding his expression and gestures.

At the time, there were two schools of thought concerning expression. The psychologist Silvan Tomkins followed Charles Darwin in thinking that expressions are innate and universal. Darwin had written in The Voyage of the Beagle that when he met the Fuegeans, a wild people, he couldn’t understand what they said but he thought he could understand their emotions. The anthropologist Margaret Mead, on the other hand, thought that a smile meant a totally different thing in another culture, that it’s a symbolic, totally cultural product. She showed that in some cultures people smile at funerals, so clearly a smile represents grief in some places, whereas it means happiness in others, and she therefore concluded that expression is a purely cultural product. She thought that any agreement about what expressions mean was a result of cultural contamination, of people watching the same movies and TV shows.

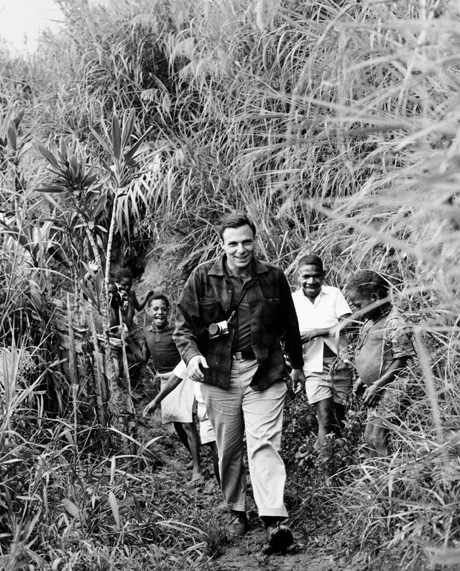

It was clear to me that the way to settle the issue was to find a people who had had no contact with the outside world. In 1967 and ‘68, I went to Papua New Guinea, and spent time in the jungle there with one of the few surviving stone-age cultures. I would show them photographs—they’d obviously never seen photographs before—and ask them to make up a story, to tell me what happened before and after the picture was taken. They did it because I would give them a bar of soap or a cigarette, and they like both.

The next year I went back, and this time, to refine my results, I told them a story and asked them to choose a picture depicting the expression that best represented that story. I returned a hero; I had left a lot of audiotape that I’d not used and they had woven it into jewelry—it was all over, they loved the audiotape. And I was a respected man because they had said that if I died, they would eat me, and they only ate people they respected.

If expressions are universal and innate, what is the expression for shame?

As best as I can determine, shame doesn’t have its own signal. And neither does guilt. They’re very hard to reliably distinguish from the family of emotions: sadness, disappointment, grief, discouragement, and anguish. It’s not that I think shame and guilt are the same; it’s just that they are the same in signal. Now, if I was an evolutionary psychologist, I could make up a story as to why shame wouldn’t have evolved its own signal. The last thing you want when you’re ashamed is for others to know you’re ashamed, because if they discover it, they will be disgusted with you. Guilt is about an action: I can undo guilt by confessing, by doing penance of various kinds. You can excuse guilt. But disgust is about the person. And you’re never going to forgive me if you really are going to be disgusted—you’re going to want to get away from me. Shame is a response to prevent the other person’s disgust, and there is a lot of self-disgust intermingled with that shame.

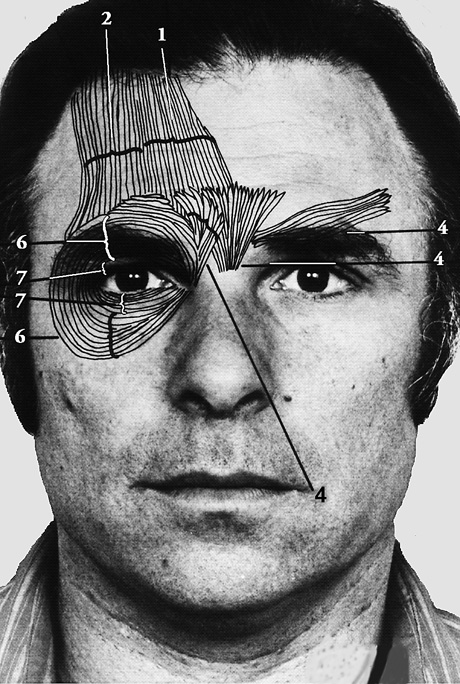

Can you say what a sad expression, the expression you describe as most closely related to shame, would be in terms of the Facial Action Coding System, in which you assigned numbers to the forty-three muscles of the face, and itemized which are used to create a given expression?

Yes, it’s a one-four-six-fifteen, sometimes with a slight seventeen. There are 10,000 combinations of facial muscles that can occur, of which about 3,000 I have identified as meaningful. And we’ve catalogued all of them. It’s amazing that, before my study [co-authored with Wallace Friesen], people didn’t know the answer to the question of how many different expressions a human being can make. It’s as if nobody had climbed Mount Wilson; it’s there, how could you not know it? The face is so interesting.

There are certain muscles that are much harder to activate than others, even for someone practiced like me. When we were codifying the expressions, I often had to ask a surgeon in the anatomy department to stimulate my facial muscles with a pin in order to verify that I was actually moving the muscle I thought I was moving, because the muscles lay one on top of each other. I’ll show you one expression that’s very difficult—Woody Allen does this all the time [Ekman contorts his eyebrows into an angst-ridden circumflex]. Most people can’t do it.

Can I do it? [The interviewer attempts to make the same face.]

With a mirror, you’d be able to learn to do it. You’re on the way. Now you have to learn to stop blushing! There is a great chapter on blushing in Darwin’s book on expression [Ekman edited the third edition of Charles Darwin’s The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, 1872]. He doesn’t use the word embarrassment. Embarrassment is very interesting. The seven core emotions—anger, disgust, fear, joy, sadness, surprise, and contempt—have a snapshot expression; cameras can capture them easily, but you can only pick up embarrassment if you can watch someone over a series of three to five seconds. It’s not a snapshot. Of course there’s blushing, and as Darwin pointed out, blushing is not shown in every race of mankind; blacks blush but you can’t see it. There is no other emotion that you can’t see on blacks but you can see on whites.

Darwin also wrote that blushing was a kind of veil of love. He connected it with piety, and with shame. He cited a Chinese expression, “to redden with shame.” What role would blushing have in relation to shame?

One of my big arguments with a lot of psychologists, linguists, and anthropologists is that words are representations of emotion and it’s very hard to represent the same emotion precisely with the same word in different cultures. There are emotions like schadenfreude, which Germans have a word for, and we don’t. Does that mean we don’t enjoy the suffering of our enemies? No, we just don’t have a word for it. Tahitians don’t have a word for sadness or grief, but you’ll see the same pattern of behavior occur in the same social context. So one has to be very careful not to be misled by words, particularly when they are translated from another cultural setting. That’s why in the field I prefer to use stories than words. When I ask someone how they would respond to the death of a healthy male child, I know there isn’t a culture I could go into where they wouldn’t understand that idea, and they’ll associate it with a particular expression.

Now, is shame related to embarrassment? Darwin said, and there’s no reason to question it, that embarrassment is caused by undue attention to the self. It can be caused by flattery; you could say, “Oh, what a smart young fellow you are,” and it gets you to blush. With a woman, if she’s a blusher, just tell her how attractive and beautiful she is. But shame is really, in my thinking, something you ought to hide.

Darwin does say that a man who feels thoroughly ashamed at having lied can feel thoroughly ashamed without blushing. But if he’s detected, if he’s suspected of having lied by someone he respects, he will blush.

He’s wrong. I have an article, “Darwin, Deception, and Facial Expression,” in which I review the six sentences in Darwin’s expression book where he talks about deception. Most of what he writes is wrong. It’s interesting, but it’s wrong. I’ve done a lot of original research on that question, and people who are ashamed don’t blush.

He’s almost trying to distinguish, I thought, between shame and guilt, because he connects blushing with shame. He says that if you feel guilty before God, if you’re very religious, and you feel that God is omnipotent and watching you all the time, you won’t blush. So blushing is a signal of shame and not guilt.

I don’t think that’s right, either. It’s nice that Darwin was wrong about a few things—in the Expression book he was working with mainly anecdotal rather than observational data. If you look at his other major works, he relied upon an enormous amount of raw data, but in the expression book all he had were the responses to the photographs he sent to various correspondents around the world. And, regrettably, he fed them the answers he wanted to know, which is not the right way to proceed.

I’ve spent a lot of time studying serious liars, that is, ones who could lose their freedom if they get caught, or certainly their reputation, or their job. One can lie about almost anything. If you take the example, which is the one I use most often with police, that you suspect someone of being a child rapist, there’s a reasonable likelihood that most child rapists are ashamed, and they are concerned that you’ll be totally disgusted with them if they admit it. So what you want to do is shift them from shame to guilt, because when you’re guilty, you can expiate it, and if you confess and say how sorry you are, even go to jail, you can make up for it and get a clean bill of health.

How can someone steer a person from shame to guilt by observing facial cues?

You don’t need the facial cues at all. You just need to understand shame and guilt. You say to the suspect, “You know, the way those mothers dress up those little girls in those sexy outfits, I mean, I’ve had those fantasies too, I haven’t acted on them, but I could understand how, in a moment of weakness—I mean, they’re just trying to get you to feel sexual about those little girls, they shouldn’t do that. And if you tell me about it, you’re going to feel a lot better.” As long as there’s shame there, let me tell you, you’ll get a confession if you shift it to guilt.

That’s interesting, because psychotherapists often talk about the shame/guilt cycle, and how to break it, how to stop shame turning into humiliated fury or whatever. For Freud, shame is a reaction-formation and a defense against excessive pleasure, against libidinous feelings. Silvan Tomkins talks about shame in that way in his book The Faces of Shame. He says that shame is deployed to diminish interest and excitement when it would be socially unacceptable. Do you think that’s true?

I don’t know. It seems to me unlikely that that’s the only source of shame. Tomkins was a philosopher, but he was psychoanalyzed according to Freudian analysis. You can see a little Freud in there, which doesn’t mean it’s wrong, but is that a sufficient explanation of all the circumstances in which shame occurs?

Do you think the face never lies?

No, it lies all the time. It lies more often than it tells the truth. But micro-expressions, the very fast signs of concealed emotion that occur in 1/25th of a second, never lie. Most people miss them. But we are, much to my surprise, learning that we can teach people to recognize them very quickly, even after an hour of training. People find out what I do at a party or something and they say, “Oh, you can read my mind.” I can’t read your thoughts, I can’t know what triggered your emotions, but I probably know what you’re feeling even if you don’t want me to know. Because the face reveals it in a number of ways, probably in a micro-expression that you can’t prevent. Most people won’t see it, but I will—I’ve learned how to see them.

How has having that skill changed your life?

Sometimes I know more than I would like to know, but you can’t turn it off. It’s like when you learn to read music, you hear music differently. You’ll never hear it like you heard it before you could read music.

My methods are now being used by everybody from Procter & Gamble to the State and Defense Departments: the primary thing people want to be able to understand using my techniques is what another person is feeling. I teach non-coercive methods of interviewing and surveillance of public places. Whether the person you’re talking to is a witness, an informant, or a perpetrator of something that’s already happened or is about to, you’re never going to get them to cooperate and open up to you unless you know how they’re feeling.

For example, even second-generation Japanese rarely maintain eye contact with someone who’s an authority. That doesn’t mean that they’re lying; it’s just that they’re being respectful, and we teach people to be aware of those sensitivities. There are also feelings that the other person is having that they might not even know they’re having. One of the interesting things about a micro-expression is that it occurs not just with deliberate concealment, but it occurs with repression. And so you could see on someone’s face an emotion they’re not aware they’re feeling. They may not ever become aware of it, but you may be able to take a counter-move and better guard how you talk with them.

And what are your boundaries? Do you worry that your teaching might ever be abused?

I get inquiries from the Chinese, the Iranians, and the Syrians on how to use my work, which I don’t respond to. I can’t know everything our government is doing, both because it’s too vast and because I don’t have a security classification, but, in the last three days, I’ve met people from secondary agencies who are using my work and they’re telling me they want to use it more because they feel they’re having such success with it in catching, as they put it, bad guys, people who are perpetrating crimes.

When you hear about interrogation techniques in Abu Ghraib and things like that, doesn’t that make you worry about the possible abuse of your system?

I think that’s the result of not teaching people effective non-coercive techniques— the chief ringleader of that business, where they were putting ropes around inmates’ heads and photographing them, was fired from his old job as a prison guard for abusing prisoners. And then they sent him to Abu Ghraib. He’s now in jail. The tragedy in my mind, the big tragedy, is that we’re not preparing people for the job we’re giving them. I can go on and on about that, but it’s not my area. I do worry about the misuse, but I operate on the assumption that the more we understand about each other, no matter what our context is, the better off we are. And although there will be occasions where that might not be the case, the side of the sword that facilitates mutual understanding is a sharper side than the one that facilitates exploitation.

Why wouldn’t you teach CIA officers to be better liars?

I don’t run a school for liars. I run a school for lie-catchers. And there are multiple reasons for doing that. One is, I don’t want more lying. I think it just makes the system noisier. I’ve been asked to train political candidates to make them more electable. I’m not going to do that, even if I like that candidate and want them to win. I don’t want to further distort the system. I won’t do jury selection for the same reason. Crooked lawyers do use my methods for jury selection; I’m opposed to such attempts to try and defeat the system by creating biased juries. There’s a second reason for not running a school for liars and that is, it probably won’t work. I know I can teach people to catch liars, but I have serious doubts if I can make people better liars unless they’re already natural actors. If they want my help, it’s probably because they’re pretty bad to begin with.

Why do you think your job exists? Why are we so bad at decoding the expressions of others?

We don’t always want to know the truth. Do you want to find out that you’ve hired someone who’s embezzling from your company? Do you want to find out that your children are using hard drugs? Do you want to find out that your spouse is cheating on you? This is the Chamberlain phenomenon. Chamberlain wrote, on the night after his first meeting with Hitler, “I could tell from the look on his face that he’d be telling me the truth.” And, of course, Hitler was lying as deliberately as he could—the order for the mobilization for the invasion of Poland had already been given. He just wanted to be sure that he caught everyone with their pants down, and it didn’t take long for Chamberlain to find out the truth. Most of us want to put off bad news. Why? The truth can be painful and you often avoid it.

It must be hard for your family not to succumb to the panopticon effect and feel that you’re permanently invading their privacy. Even if you don’t see it, they’ll think you have.

No, I think they really think I miss these things. I don’t make much use of it, because that’s not my job as a spouse or a parent, unless I see something that’s really troubling. And with my daughter, I’ll almost always say, what are you upset about? For years they think they’ve gotten away with things because I haven’t said anything about it. I think they feel more relaxed than they should.

Paul Ekman’s books include Why Kids Lie: How Parents Can Encourage Truthfulness (Penguin, 1991) and Emotions Revealed (Holt, 2007).

Christopher Turner is an editor of Cabinet. His book, Adventures in the Orgasmatron: How the Sexual Revolution Came To America, is forthcoming from Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.