Ingestion / Power Hungry

Dining with the Committee of Public Safety

Ben Kafka

“Ingestion” is a column that explores food within a framework informed by aesthetics, history, and philosophy.

In the final years of the eighteenth century, the Göttingen physicist, tinkerer, and man-about-town G. C. Lichtenberg—whose habit of procrastination, Wikipedia helpfully tells us, led to his “failure to launch the first ever hydrogen balloon”—recorded a series of observations on human nature. Among these was a proposal for a “Compass of Motives,” which would allow intrepid explorers of individual character to chart human inclinations with a greater degree of precision. “The motives that lead us to do anything might be arranged like the thirty-two winds, and might be given names accordingly, for instance, ‘food-food-fame’ or ‘fame-fame-food.’”[1]

This observation was a favorite of Freud’s, who took it up twice, the first time as farce, the second time as tragedy. In Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious (1905), he offered Lichtenberg’s proposal as an example of the role of absurdity in the formation of jokes. The juxtaposition of fame and food, ambition and appetite, struck him as ridiculous, at least at the time. But he was no longer laughing when he returned to Lichtenberg’s observation in an open exchange of letters with Albert Einstein, published by the League of Nations’ International Institute for Intellectual Cooperation as Why War? (1933). This time Freud invoked Lichtenberg’s compass of motives as a genuine psychological insight. Our drives, our motives, are never pure, he suggested. They are always mixed, fused, alloyed. The “food” in the Lichtenberg allusion seemed to be a nod to Einstein’s suggestion that there was a deadly “power hunger” at work in the world.

“Power hunger” is almost always taken metaphorically, that is to say, as mankind’s supposedly immutable appetite for power. What if we took it literally? What if we took it to mean the kind of appetite you work up after a long day at the office making decisions about national security or monetary policy? This can be exhausting. Indeed, physiologists have spent considerable time and government research funds quantifying the amount of energy expended on various office tasks, from sitting at one’s desk writing memos to the various subcategories of standing (“light/moderate,” “duplicating machine”). The standard reference on this subject makes no mention of how much energy it takes to order a bunch of people around, but it does tell us that “sitting-meetings, general, and/or with talking involved” consume 1.5 METs—a unit representing the ratio of working metabolic rate to a resting metabolic rate—while conducting an orchestra consumes 2.5 METs.[2] Such measurements can’t be taken too seriously, of course. But they nevertheless signal something important about the kinds of material resources—some abundant, others scarce—that make state power possible on a daily basis. The hunger for fame, perhaps. The hunger for lunch, definitely.

As usual, to reinvigorate our understanding of the history and theory of power, we can turn to the French Revolution. More than two centuries later, it remains both eerily familiar and irreducibly strange. The Committee of Public Safety is remembered more for the blood on its hands than for the grease on its fingers. During the revolutionary Terror of 1793–1794, its twelve (later eleven) members implemented a series of more or less ruthless measures designed to protect the young republic from its enemies, internal and external, real and imaginary. “If the mainspring of popular government in peacetime is virtue,” Robespierre said in his famous discourse on political morality, “the mainspring of popular government in revolution is virtue and terror both: virtue, without which terror is disastrous; terror, without which virtue is powerless.”[3] Of course it took a lot of effort to maintain virtue and terror both in a nation of twenty-eight million people. The republic was at war with the British, the Austrians, the Prussians, the Spanish, and the Dutch. And it was at war with itself, as angry royalists, refractory priests, and their sympathizers in the Vendée fought against Parisian control. Bad harvests, sabotage, hoarding, and profiteering added to the difficulty of supplying the troops, feeding the populace, and managing the nation.

What’s more, office hours were brutal; during the daytime, committee members would work in their separate bureaus, overseeing large staffs of clerks and copyists, handling hundreds of reports, circulars, memos, and other documents. In the evening, they would assemble in a chamber high up in the Tuileries, the palace once located between the Louvre and what is now known as the Place de la Concorde, but at the time was known as the Place de la Revolution. The chamber, which had formerly served Louis XVI as a private office, was called the “Green Room,” after the color scheme of its wallpaper and conference table. Here, Robespierre, Saint-Just, Carnot, and the other committee members—who didn’t much like one another—would report on their respective departments, argue about proper procedure, come to agreements, and plot courses of action. These meetings usually lasted until three or four in the morning. Then they got to go to bed.

There are no records of what was said or eaten in the Green Room during the Terror. What scant evidence I’ve been able to find suggests that the committee members were largely left to fend for themselves. Carnot later recounted: “I worked so hard that I did not even give myself time to go dine with my wife, even though I lived on rue Florentin [just a few blocks away]. I dined each evening on the terrace of the Feuillants, with food from a caterer named Gervais.”[4] After one especially bitter argument with Robespierre, the latter had Carnot’s caterer arrested, just for the heck of it. Or so Carnot later claimed—he was facing accusations of colluding with the terrorists and was doing everything he could to distance himself from the “Incorruptible.”

On the night of 27 July 1794, the regime’s opponents staged a coup, invading the Green Room and arresting several committee members. Robespierre shot himself in the face as he was being wrestled to the ground; with no linen on hand to make bandages, his captors tried to staunch the bleeding with sheets of paper. The Committee of Public Safety, which had been functioning as a largely autonomous executive power, deciding everything from postal routes to peace treaties, was purged of its most militant elements. The night is best known by its date on the revolutionary calendar, 9 Thermidor—and in French “Thermidorian” is immediately associated with “reactionary.” Not only were Jacobins hunted down and punished—Jacobin women, for example, were stripped naked and flogged in the streets by gangs of so-called “gilded youth”—but the entire culture took on a gothic cast, with flourishes of extreme luxury, even decadence, framed by a general morbidity.

• • •

At this point, the archives suddenly get very interesting, at least from a culinary perspective. I was going through old payroll records in France’s National Archives when I came across a series of bills and receipts showing, in splendid detail, how the committee fed itself from one day to the next. Instead of forcing its members to find dinner on their own, the reformed Committee of Public Safety began to order its meals in.

Food made its way into the committee by three routes. The first was a supply of snacks and beverages brought in by the committee’s clerks, who were reimbursed for the cost. One receipt is titled “Itemized Expenses Incurred both for the Bureaus and the Central Office of the Committee of Public Safety during the month of Brumaire Year III of the Republic One and Indivisible”—roughly November 1794. In it, we see that the committee and its bureaus consumed 178 livres‘ worth of “syrups”—sweet concentrates to be mixed with water—and “victuals,” which could mean pretty much anything. To give some sense of relative prices, this was approximately a month’s salary for a low-level clerk. Another seventy-five livres and change went to cheese and fruit; half as much again to biscuits and little cakes. These were mainly provided by a certain Madame Uzépy, the only woman to find employment as a clerk in the Committee of Public Safety; she was hired after her husband was killed on an official mission. It seems that her son worked there too—it was not uncommon for boys as young as twelve to perform various ancillary office tasks. And then there was the wine. The offices of the subcommittee responsible for military affairs consumed sixty-six bottles over the course of the month; thirty-one more went to the conference room where the committee itself met; eighteen more to the library.

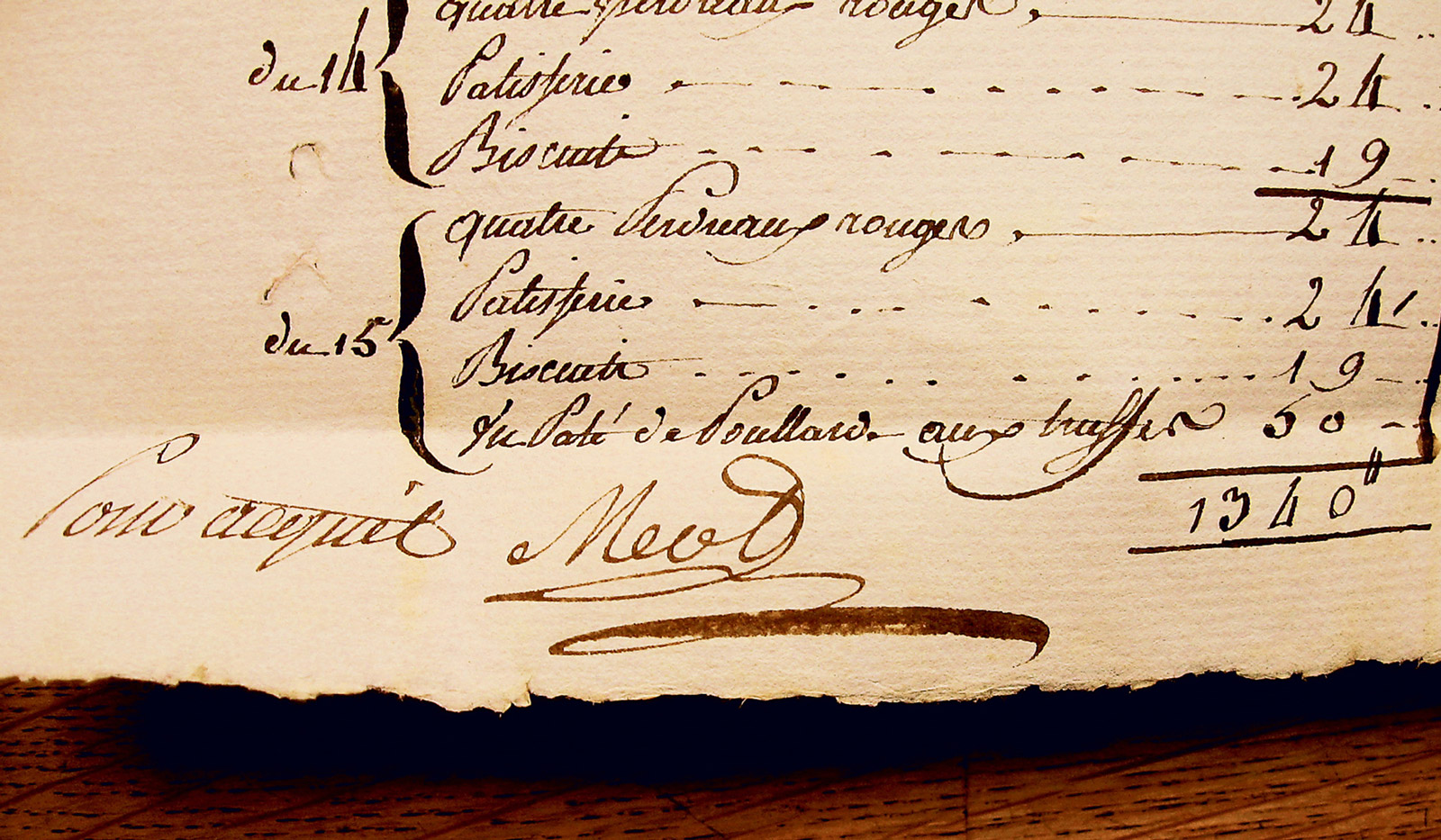

This is routine stuff, not that much different from what any workplace might consume, except maybe a bit boozier. Far more interesting is what the committee itself ate on a daily basis. And this we can determine in still more detail. Another document, from the revolutionary month of Pluviose Year III, or approximately February 1795, shows a day-by-day inventory of the catered meals at the post-Thermidor Committee of Public Safety. On the first of the month, a ham in aspic, four red partridges, pastries, and biscuits. On the second, pastries and biscuits. On the third, a veal tongue, four more red partridges, and the ubiquitous pastries and biscuits. And so on.

Now granted, these inventories aren’t menus, and don’t tell us much about how the dishes were actually prepared and presented. I was particularly curious about all these red partridges—a relatively banal game bird that could not have been that much fun to eat day after day. (Alexandre Dumas’s culinary dictionary, published in 1873, explains that the grey partridge was much preferred in the eighteenth century.)[5] What we can say with some certainty is that the execution of these meals must have been creative enough and elaborate enough to compensate for the monotony of the main ingredients. This can be gathered from the signature on these bills, which belonged to Méot, one of the most celebrated restaurateurs of the revolutionary era. He had opened his restaurant in 1791 after his former employer, the Prince de Condé, fled to Coblenz to organize a counter-revolutionary army allied with the Austrians.

Méot’s eponymous restaurant was famous for its superb cuisine, sumptuous decor, and, above all, its powerful clientele. Louis Sébastien Mercier, the great chronicler of Parisian life in the final decades of the eighteenth century, described the meals at Méot as the best in Paris, and thus anywhere in the world. The food was “warm, prompt, well-made,” the dining rooms “gilded, sculpted, theatrical.” Finally, the prices were the highest in Paris.[6] Méot’s bill for the month of Pluviose Year III, for instance, came to 2623 livres, or about fifteen times a clerk’s monthly salary. In the decades following the French Revolution, Méot would be lauded as a pioneer by both Grimod de La Reynière and Brillat-Savarin. In addition to members of the Committee of Public Safety, who are said to have drafted France’s first republican constitution over lunch at Méot in June 1793 (earning the document the nickname la constitution Méot), famous revolutionary customers included Marie-Antoinette’s judges, who celebrated her condemnation at the restaurant in October of the same year.

Given Méot’s legendary extravagance, how might the Committee’s red partridges have been prepared? Though we have no recipe from Méot himself, one of his greatest rivals, Antoine Beauvilliers, later published one in his Art of Cookery (1814). Chef Beauvilliers instructs the cook to take three partridges, remove the feathers, trim the claws, stuff them with a pound of truffles and a half pound of lard that’s been mixed with truffle pairings, sew the cavity, and truss the legs. Fill a pot with lard, ham, the fat of veal kidneys, a mirepoix, a bouquet garni, half a glass of white wine, a spoonful of consommé, and a little salt. Gently lay the partridges breast-down on top of this mixture, cover with slices of lemon and bacon, bring to a boil, lower to a simmer, and braise for forty-five minutes. Drain, carve, and serve with a Perigord sauce—a madeira-based sauce embellished with diced truffle.

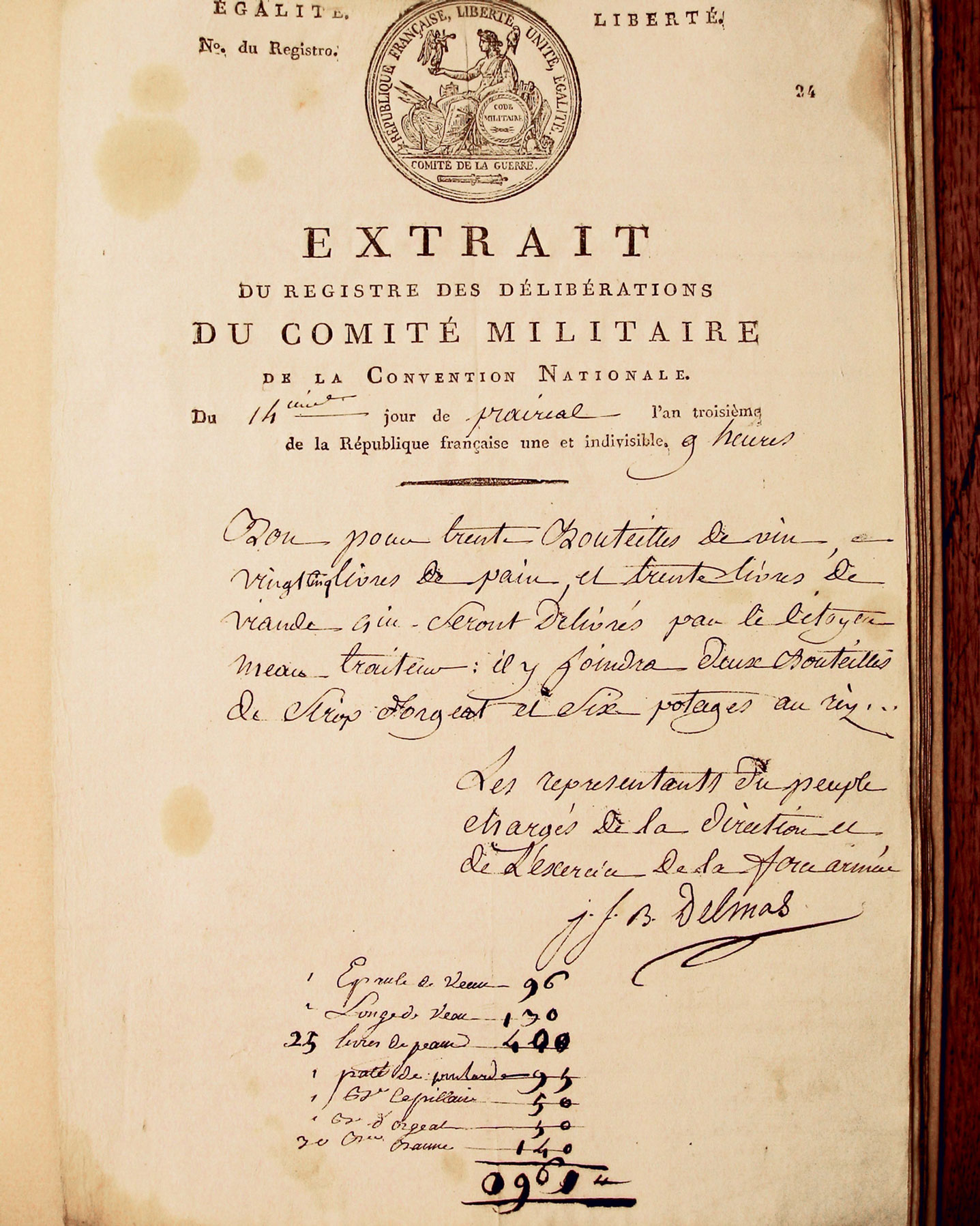

There is one final route that food took into the committee’s offices and stomachs, one that seems to be associated with special occasions, and that attests to power hunger at its most robust. Unlike the snacks supplied by the committee’s clerks, or the meals delivered daily by the caterer, these were ordered in advance, with the ingredients stipulated by the officials themselves. On a standard pre-printed form of the sort used for recording official decisions, we find a handwritten note, which says: “coupon for thirty bottles of wine, twenty-five pounds of bread, and thirty pounds of meat to be delivered by Citizen Méot, caterer. He will also include two bottles of barley syrup”—a sweet dessert sort of drink, generally non-alcoholic—“and ten rice porridges.” And it’s signed “The Representatives of the People Charged with the Direction of the Armed Forces, J. F. B. Delmas.” Beneath, tabulated in what appears to be Méot’s handwriting, though it may be that of one of his assistants, we read “one veal shoulder, one veal tongue, one paté of poulard,” and the rest of the items that Delmas had requested. Best of all—and it’s a nice touch—what look to me very much like grease stains.

- Lichtenberg, quoted in Sigmund Freud, Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious [1905], in Freud, The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, ed. and trans. James Strachey, with Alex Strachey (London: Hogarth, 1953–1974), vol. 8, p. 86. Translation slightly modified.

- Barbara E. Ainsworth, William L. Haskell, Melicia C. Whitt, et al., “Compendium of Physical Activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities,” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, vol. 32, no. 9, suppl. (2000).

- Maximilien Robespierre, “On the Principles of Political Morality that Should Guide the National Convention in the Domestic Administration of the Republic,” in Robespierre, Virtue and Terror, trans. John Howe (New York: Verso, 2007), p. 115.

- Réimpression de l’ancien Moniteur (Paris: Plon, 1863–1870), vol. 24, p. 74 (10 Germinal, Year III / March 30, 1795).

- Alexandre Dumas, Grand Dictionnaire de Cuisine (Paris: Alphone Lemerre, 1873), p. 814.

- Louis Sébastien Mercier, Le Nouveau Paris [1799], ed. Jean-Claude Bonnet (Paris: Mercure de France, 1994); pp. 608–609. On restaurant culture in the revolutionary era, see Rebecca Spang’s wonderful study, The Invention of the Restaurant: Paris and Modern Gastronomic Culture (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000).

Ben Kafka is an assistant professor of media studies and history at New York University. He is working on a history of paperwork.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.