Inventory / Cigninota

The mark of the swan

Christopher Turner

“Inventory” is a column that examines or presents a list, catalogue, or register.

Julius Caesar remarked that Celtic tribes in Britain considered it “unlawful” to eat swans, which were sacred birds. However, by the twelfth century they were thought to be a delicacy and were being hunted to extinction. A medieval banquet was incomplete without a swan, “stuffed with herbs and pork fat, sealed in a paste of flour and water and roasted for 2–3 hours until tender”; in 1251, Henry III celebrated Christmas with a feast consisting of 125 of them. So, to protect the species from commoners, laws were imposed forbidding anyone from killing swans except with permission of the crown. Stealing swan eggs was punished by a year’s imprisonment, and poaching birds even more severely.

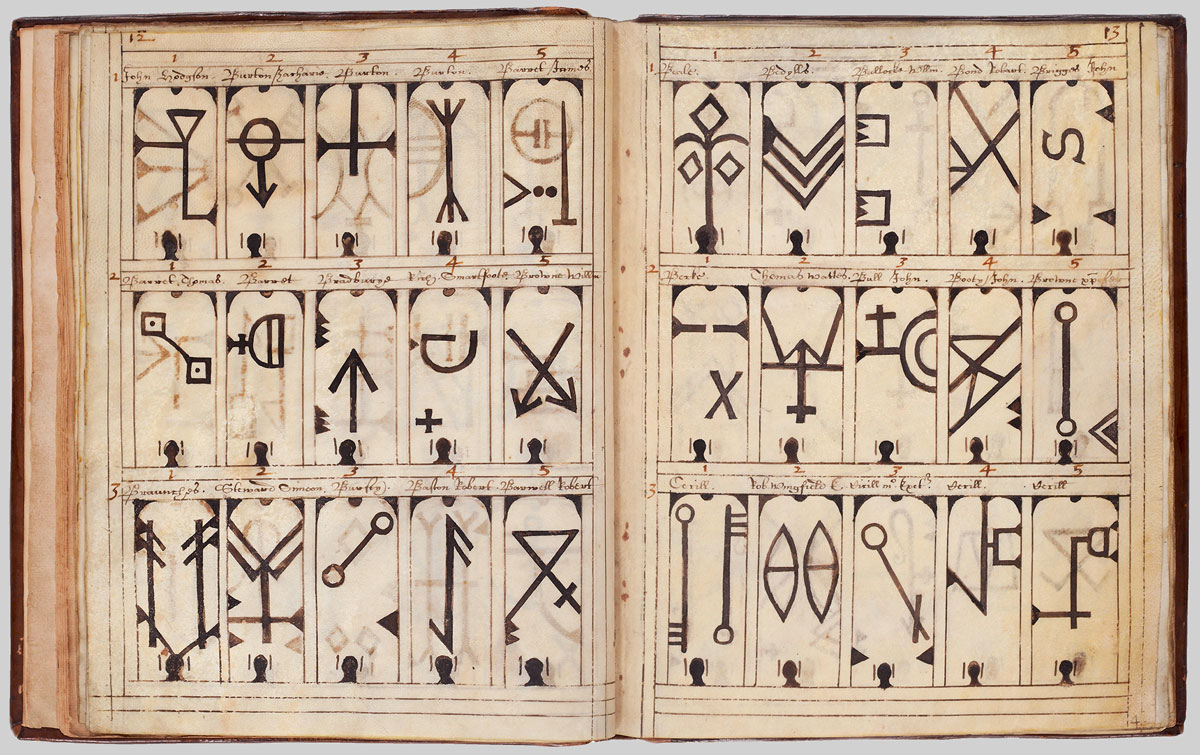

The privileged few who were allowed to breed and own swans were granted a “swan mark,” the oldest of which dates to 1230. Eventually, nine hundred members of the landed gentry were granted these proprietary badges, which were cut into their swans’ bills with a sharp knife. The combinations of rings, chevrons, keys, nicks, crosses, and letters, which often made reference to the coat of arms of the owner, were catalogued in special books of swan marks. In the sixteenth-century example shown above, each page looks like a board game decorated with Nordic runes—only the small circles that represent the black fleshy knob that mute swans, the species most common in England, have over their nostrils (referred to as the “berry”) and the black tip of each beak give a clue to their true meaning.

Once a year, all the swans on a river were rounded up and, in the presence of the King’s swanherd (who kept the index of bills), cygnets were marked with the heraldic insignia of their parents. Any unmarked swan discovered on open waters automatically belonged to the Crown and was scarred with the royal emblem, and those young birds destined for the table were taken away to ponds, or “swan pits,” where they were fattened up. When the black bills of the cygnets turned orange during maturation, their dramatic markings—sometimes referred to as cigninota—would become as visible as tattoos.

Swan, considered very tough meat, is no longer eaten in Britain. However, the Queen still retains rights to all unmarked swans, even though she only exercises her royal prerogative on a seventy-eight-mile stretch of the Thames. Since the fifteenth century, the Vintners’ and the Dyers’ livery companies have also been allowed to own swans in this jurisdiction. Every July, in an anachronistic, eight-hundred-year-old ritual known as “Swan Upping,” six boats embark on a five-day rowing trip upriver from Eton to Oxford to count and mark swans (at this time of year the mature swans are molting and unable to fly). The passengers of the royal skiff, captained by the Sovereign’s Swan Marker, are outfitted in bright scarlet blazers; when they pass Windsor Castle, they raise a toast to “Her Majesty the Queen, Seigneur of the Swans.”

The ill-tempered, hissing birds are corralled, caught with long crooks, hauled aboard by their necks, bound, taken to shore, weighed, and examined. Twenty-five years ago their bills were still chiseled with small nicks (one for the Dyers and two for the Vintners), but they now ring their legs instead. In 1964, the census recorded 1,300 birds, a number that by 1980 had dwindled to only 120—the swans were ingesting lead fishing weights, which have now been banned. There are now about 1,000 swans on this stretch of river.

Swans remain a royally protected species: the maximum penalty for killing or injuring a swan is a £5,000 fine and/or six months in prison. The last person to be prosecuted for this crime was a Welsh Muslim, Shamshu Miah. In 2006, he chose to break his Ramadan fast with a feast of swan. He stabbed one by a boating pond with a knife and was caught carrying it home in a plastic bag. “I was so hungry,” he told police, adding, “I hate the Queen.” He received a two-month prison sentence.

Christopher Turner is an editor of Cabinet. His book, Adventures in the Orgasmatron: How the Sexual Revolution Came to America, is forthcoming from Farrar, Strauss and Giroux.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.