Ingestion / Folded Allegories

Unfurling to infinity

Daniel Birnbaum

“Ingestion” is a column that explores food within a framework informed by aesthetics, history, and philosophy.

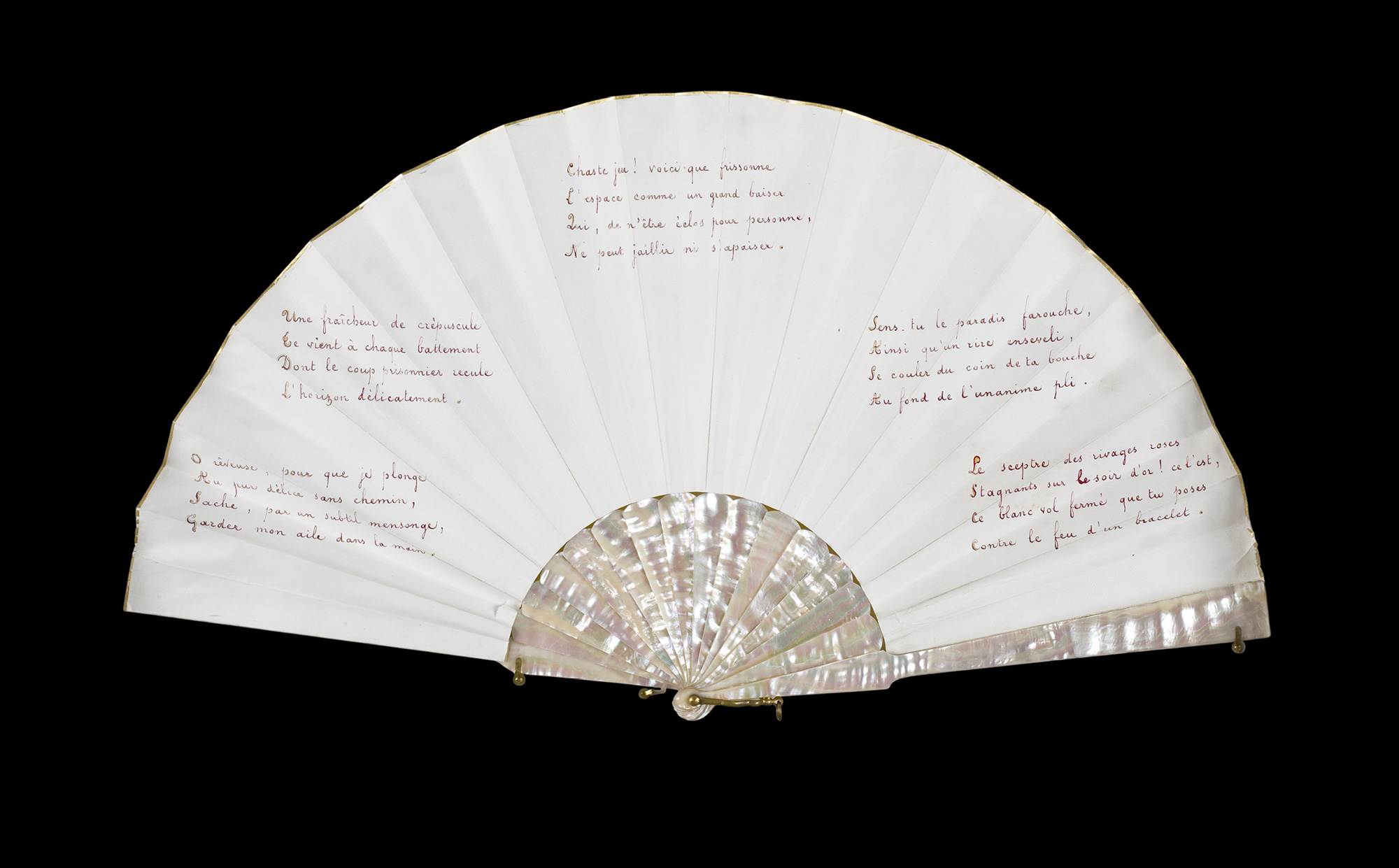

Those familiar with Gilles Deleuze’s book The Fold: Leibniz and the Baroque know that Baroque ideas did not end with the Baroque epoch. Leibniz saw in the monad an endless folded structure in which the whole universe is mirrored. The literature of Jorge Luis Borges, Pierre Boulez’s composition Pli selon pli, and especially Stéphane Mallarmé’s symbolist poetry all gently reflect such ideas. Mallarmé composed several poems about folds that he inscribed on ladies’ fans, verses he dedicated to special women in his life, such as his daughter or the beautiful pianist Misia Natanson. This fondness for glamorous pleats lends a Baroque quality to his writings. And maybe Mallarmé, who was also the anonymous publisher of the newspaper La dernière mode, paved the way for modern artists like Issey Miyake, the most famous contemporary creator of pleats. Of course, folds were not a seventeenth-century invention but, writes Deleuze, “the Baroque trait twists and turns its folds, pushing them to infinity, fold over fold, one upon the other. The Baroque fold unfurls all the way to infinity.”

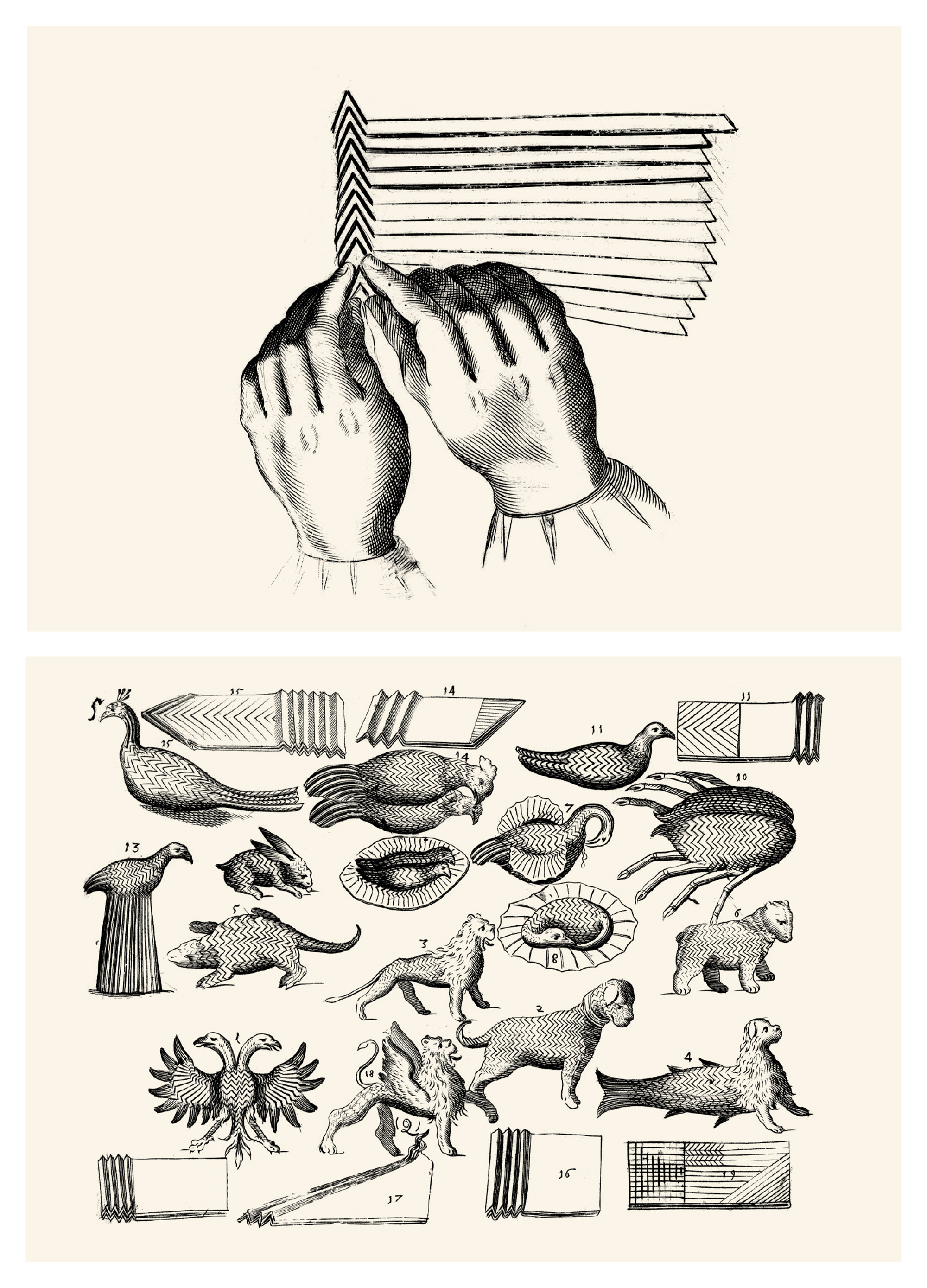

If it weren’t for the methodical spirit of Matthias Jager of Bavaria, the Leon Battista Alberti of the folding arts, we would have almost no knowledge of how the Baroque vogue for folding extended to the dinner table. Jager taught under the Italianized name Mattia Giegher at the University in Padua, and in 1639 published Li tre trattati, a set of three treatises, one of which constitutes the first instructional manual for the artistic folding of napkins. Alongside basic techniques, the book also introduced terminology—such as “mountain fold” and “valley fold”—which is used to this day. Although Giegher starts with basic folding skills, he goes on to elaborate the full extent of the Baroque imagination, turning simple cloth into fish, castles, ships, monsters, and other fantastic forms.

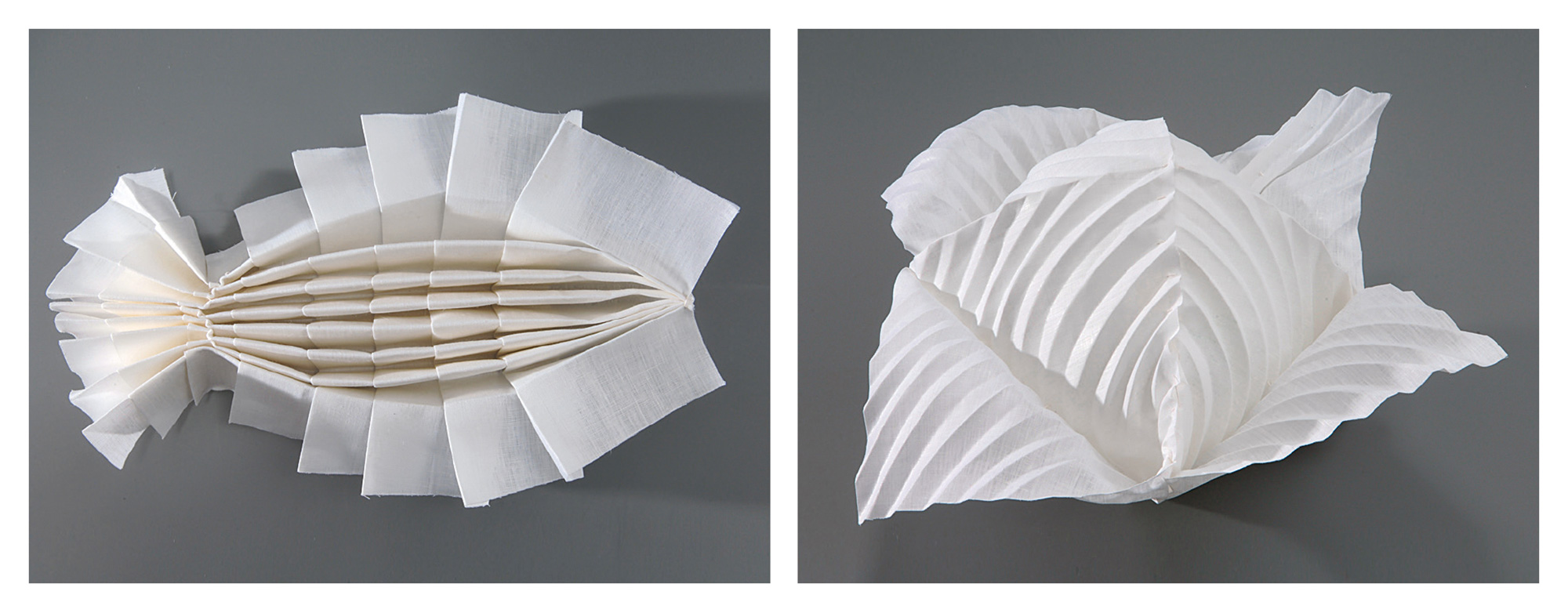

European folding culture may never be as resplendent as it was in the seventeenth century, when Nuremberg was the home of an entire school devoted to the art of folding napkins, but there are still masters of the art. Joan Sallas, a Catalan who has lived for years in Freiburg, Germany, is one of the few people in the world who knows how to fold a napkin into the lily that once decorated the tables of the Hapsburgian Kaisers, or has decoded the secret method by which the servants of the current king of Sweden, Carl XVI Gustaf, fold the royal napkins in the old manner. Having deciphered the most convoluted examples of this esoteric art, he now draws on these foundational folding techniques to develop his own unique designs and shapes. The tradition that Gieger pioneered, and that Sallas’s folded allegories keep alive today, echoes Leibniz’s conviction that every part of matter contains a garden full of plants and trees, a lake full of fish, and every part of an animal, and every drop of water, is again such a garden and such a lake.

Translated from German by David Willrich and Alexandra Zsigmond

Daniel Birnbaum is the director of the Städelschule Art Academy in Frankfurt and its Portikus Gallery. He was a co-curator of the 50th Venice Biennale in 2003 and the director of the 53rd Venice Biennale in 2009.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.