Inventory / Keep It Déclassé

The world according to the Surrealists

Colby Chamberlain

“Inventory” is a column that examines or presents a list, catalogue, or register.

It’s January 2010, and I’ve just returned from a newsstand with evidence of an industry-wide conspiracy to teach Americans remedial math. Not since Sesame Street have I encountered so many entreaties to count to ten: the year’s ten best action movies, tech companies, and art exhibitions; the ten worst television shows, sports gaffes, and celebrity dresses. As usual, print media has papered over the holiday lull with list upon list, leaving the indelible impression that our collective understanding of cultural achievement has been predetermined by our total number of fingers.

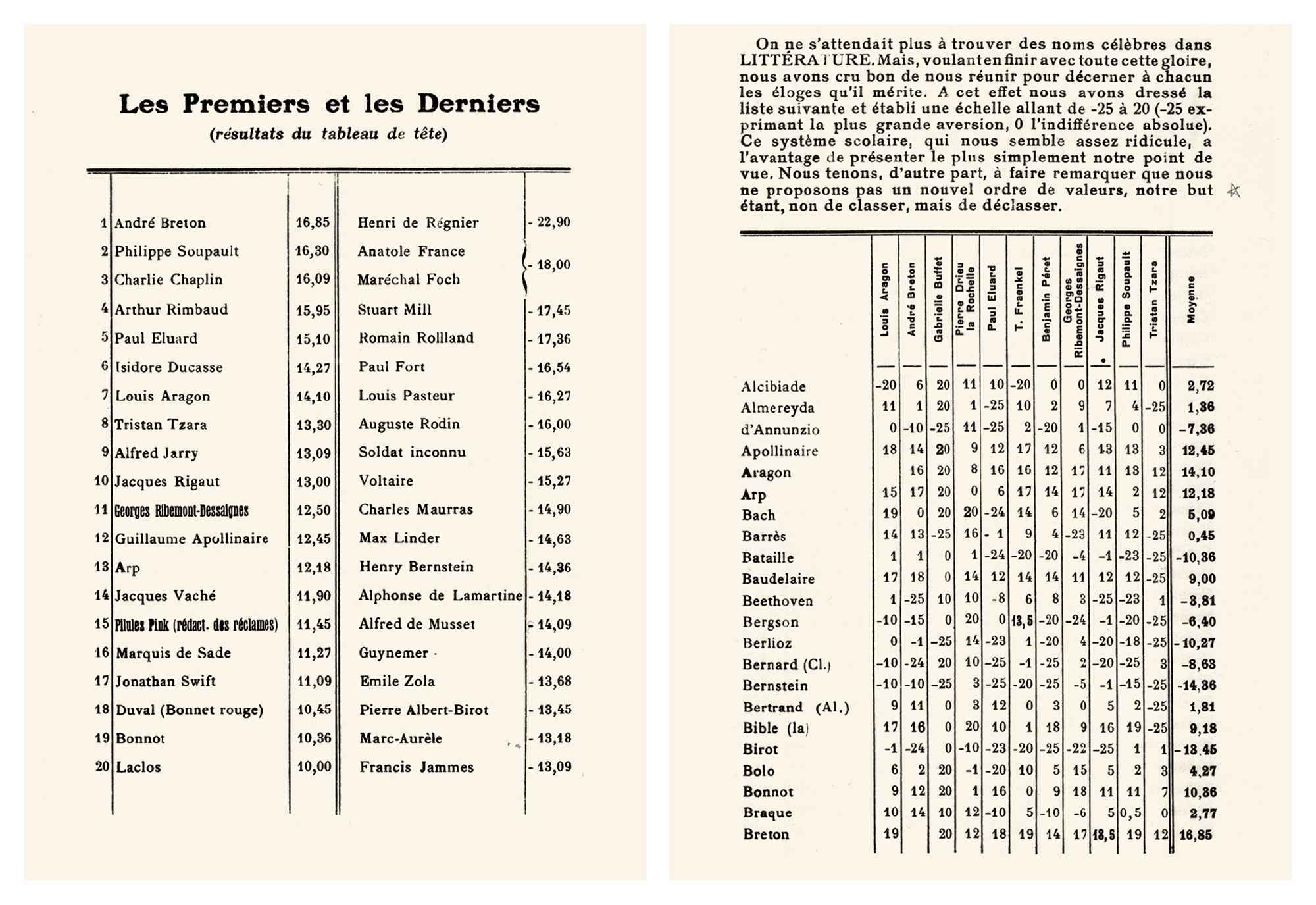

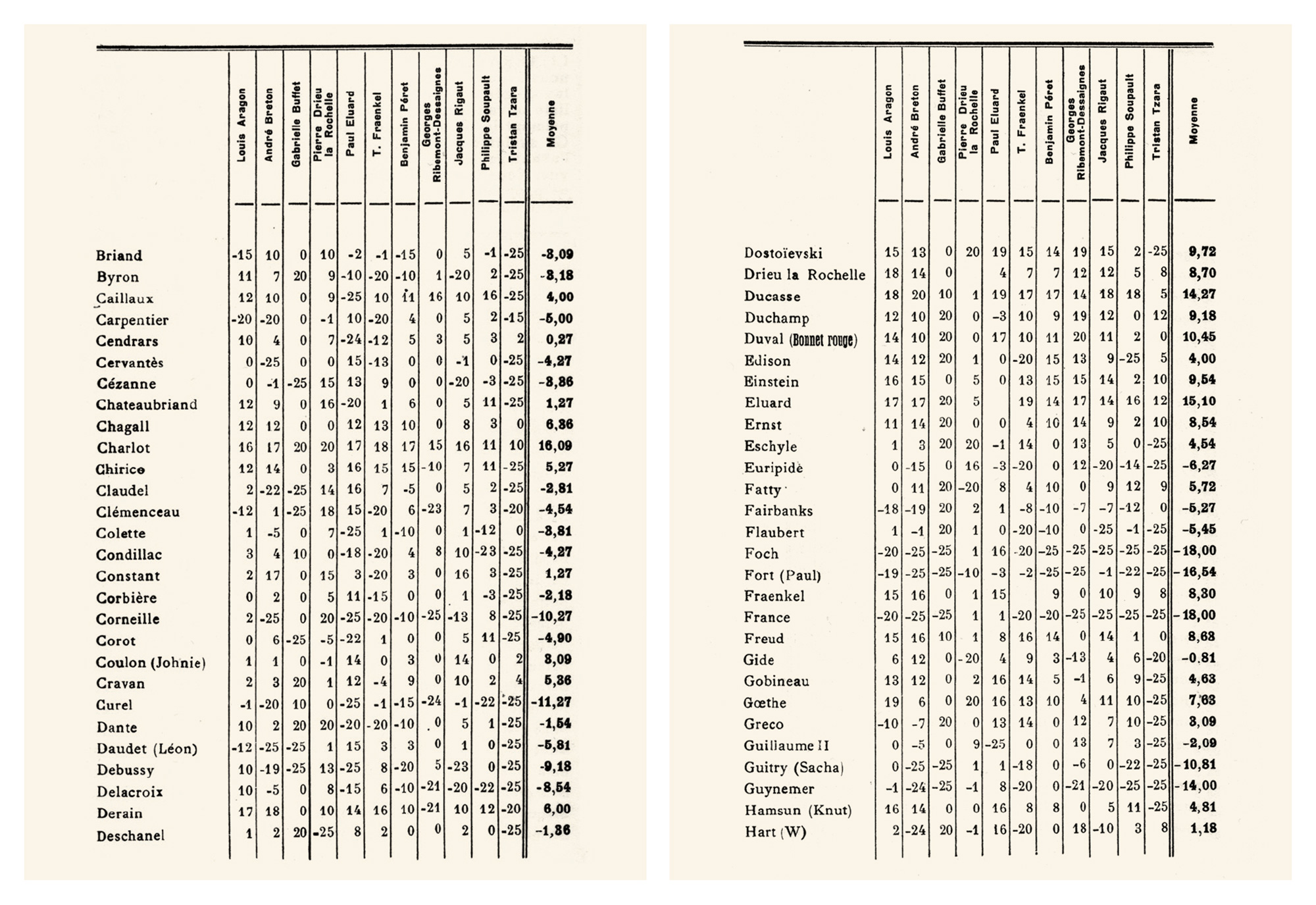

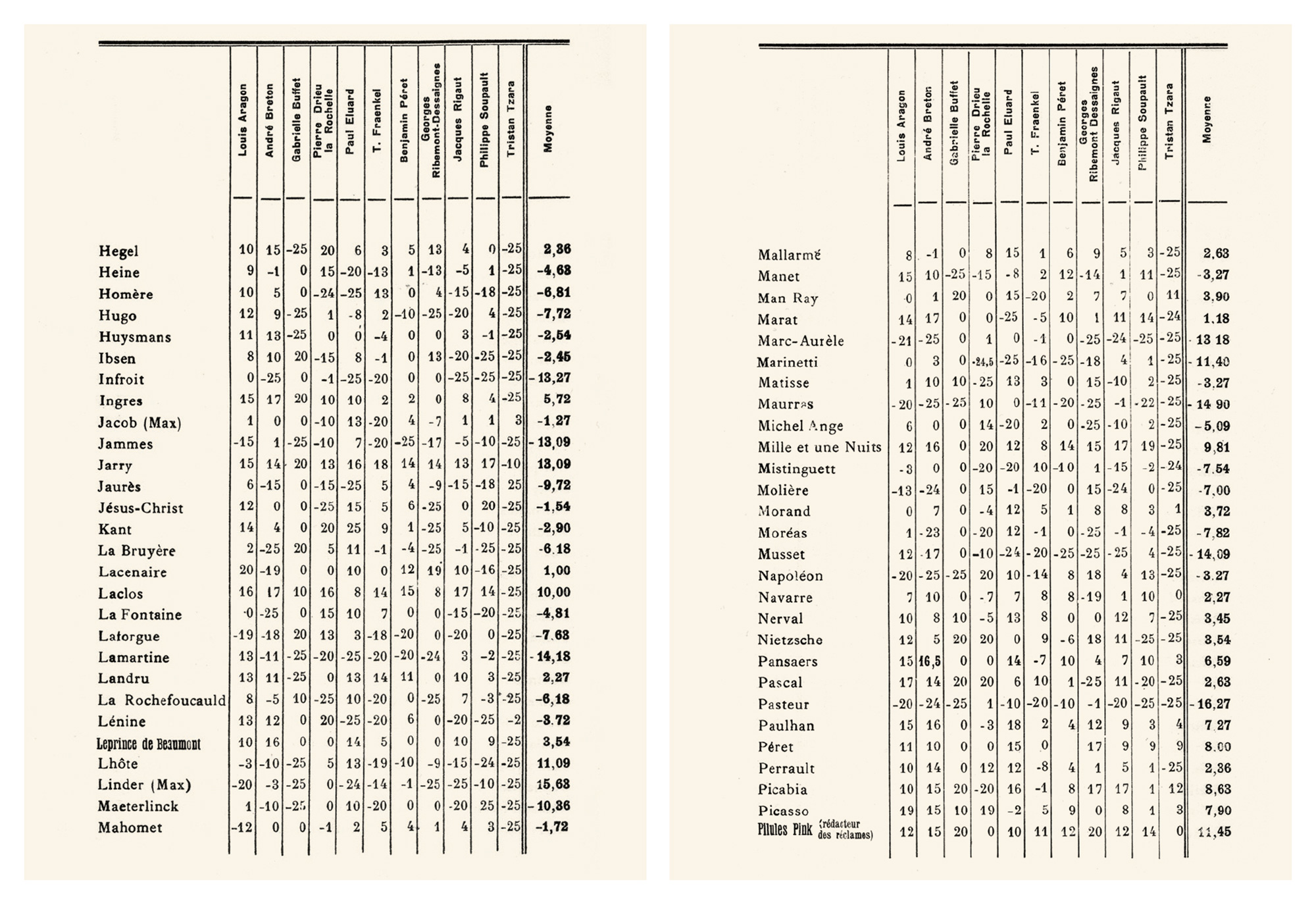

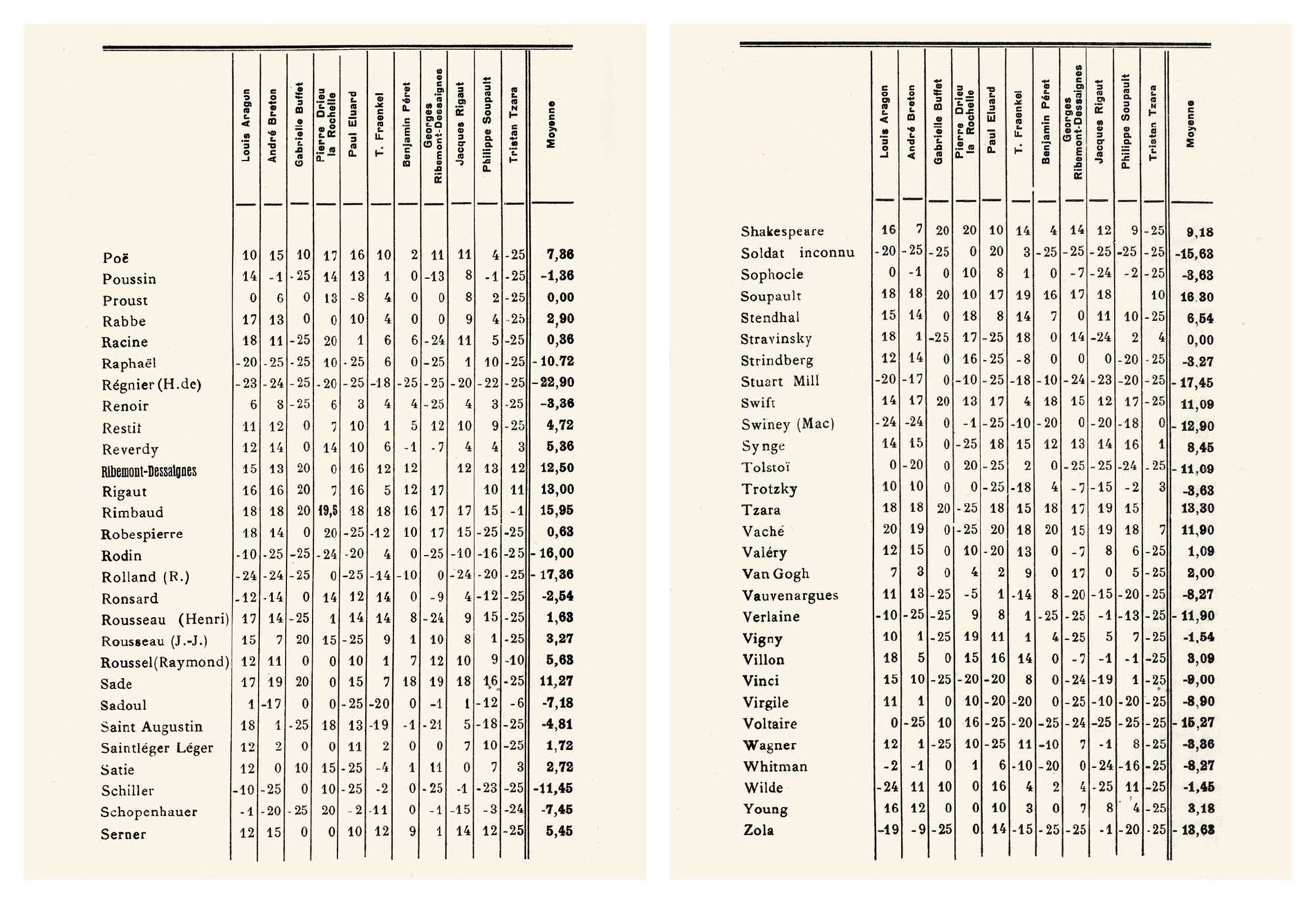

I recently found a curious precedent to all this rampant rating in the March 1921 issue of a Paris journal with the resolutely bland title Littérature. Over the course of seven pages ran a reasonably comprehensive roster of the Western canon—from Alcibiades to Zola—beside a block of numbers resembling the statistical charts on the back of baseball cards. Further examination indicated these figures were scores awarded by eleven individual judges, whose names dangled over each column; a twelfth column tallied the averages. A separate page, entitled Les Premiers et les Derniers, offered a list of the twenty highest- and twenty lowest-rated entries. The rating system was rigged to favor disdain: admiration topped out at 20, yet aversion dipped as low as -25. Zero expressed absolute indifference. Two of the judges themselves, the poets André Breton and Philippe Soupault, garnered the highest scores, 16.85 and 16.30, respectively; Proust and Stravinsky each managed a perfect 0. Comprising writers, painters, composers, philosophers, and film stars, Littérature’s chart seems to anticipate and exceed the top-ten lists clogging my local newsstand, yet it also rejects their very premise. “We are not proposing a new order of values,” the editors wrote, “our goal being not to classify [classer] but to downgrade [déclasser].” I’ve come to think of this chart, entitled “Liquidation,” as a preemptive parody.

The story behind “Liquidation” begins somewhere between Paris and Zurich, in the exchange between two publications, Littérature and Dada. Littérature was the fledgling enterprise of the ambitious Breton and Soupault, along with their friend and fellow poet Louis Aragon. For their first issue, published in March 1919, they secured contributions from the eminent André Gide and Paul Valéry; the back cover, printed on the yellow card-stock consistent across Littérature’s entire run, promised additional luminaries for future issues. By paying homage to the existing establishment, the young editors in turn received its praise. (Proust ordered his subscription with a twelve-page letter of congratulations.) They regarded their success warily. Their arriviste impulses were dampened by their impression that the French literary scene—even those figures they once valorized as rebellious—had buckled beneath the country’s postwar mood of violent, reactionary nationalism. (Guillaume Apollinaire, for instance, refused to contribute to any journal that also published Germans.) The young editors’ dissatisfaction with their former heroes increased as they heard more from the editor of the Zurich-based Dada, a Romanian born with the name Samuel Rosenstock but known to all as Tristan Tzara.

By 1919, details pertaining to the so-called Dada movement had spread across Europe: its beginnings as the Cabaret Voltaire, an eccentric performance act at the Meierei Café in Zurich; the cabaret’s founder Hugo Ball intoning sound poetry dressed in a cardboard costume of gleaming blue cylinders and a flapping collar, “like a magical bishop”; the erratic typography riddling its event posters and poetry collections; the murky origins of the word Dada itself, a concentrated blast of infantilism and absurdity. When the war ended in 1918, Dada’s members dispersed, many of them starting offshoots of the movement in new cities. Tzara mostly stayed in Zurich, yet he was everywhere. Ostensibly a poet, he worked best as a publicist: distributing the movement’s journal, Dada; writing letters to members of every city’s avant-garde circle; and sending out sensationalist press releases that blithely preyed on the credulity of newspapers. In January 1919, Tzara mailed Breton a copy of Dada’s third issue; their ensuing correspondence quickly established an intense, if geographically far-flung, friendship. In Littérature’s second issue, the young editors started publishing Tzara’s poetry and ran an advertisement for Dada soon thereafter. Their esteem for Tzara was further bolstered by a meeting with his friend Francis Picabia, a French artist of Spanish descent graced with independent wealth and hypnotic charm.

When Tzara and the Littérature group finally met in person—Tzara having arrived penniless at Picabia’s doorstep on 17 January 1920—a degree of disappointment was inevitable. The editors’ outsized expectations were undercut by Tzara’s diminutive stature, as well as his rusty French, further battered by a Romanian accent. (Perhaps Breton also suspected that Tzara was younger than he had maintained in his initial letters—though both men were born in 1896, Tzara had claimed to be twenty-seven.) Yet their hopes that the spark of Zurich would find a tinderbox in Paris soon proved warranted. The following week, they collectively organized their first performance under the Dada moniker; its culminating moment was Tzara’s vigorous recitation of a speech by Léon Daudet, an ultra-right politician, accompanied by Aragon and Breton incessantly ringing bells. (The reading provoked angry insults from the audience—“Back to Zurich! Shoot him!”—a sure sign of success.) For an event at the Grand Palais in February, Tzara pulled off perhaps his most audacious media hoax: a widely reprinted press release claiming that Charlie Chaplin had declared himself a Dadaist and would join them onstage. The ensuing crush of excited attendees heard a medley of outlandish manifestos and nary a word acknowledging Chaplin’s glaring absence. These early coups inaugurated a string of Dada events as absurd as they were anticipated; shock, it turned out, could double as both an aesthetic strategy and a means for ensuring sufficient ticket sales to cover the cost of renting a hall.

Ceaseless activity and shared notoriety held the group together for a time, but their dispositions were fundamentally at odds. For Tzara and Picabia, Dada said it all—it was pure nonsense, a giddy cackle directed against systems of belief or value (art included). Breton couldn’t shake these things off so easily. Though committed to Dada’s dismantling efforts, he intended always to construct something new. “It is absurd that poetic or philosophical ideas should not be amendable to immediate application like scientific ideas,” wrote Breton in 1921. “Surrealism, psychoanalysis, the principle of relativity must lead us to build instruments as precise and as well adapted to our practical needs as the wireless [telegraph].” Already Breton was formulating the ideas that would lead him to found the Surrealist movement in December 1924. But in the meantime he was still a Dadaist, and rather than leave the movement he decided to hijack it. Along with Aragon, Soupault, and a few additional Dada inductees, he declared the Grande Saison Dada, which promised an odd assortment of events: plebiscites, commemorations, trials, congresses. This program, seemingly more bureaucratic than artistic, was intended to evoke the violence and grandeur of a revolutionary government. As Aragon wrote: “We compared our intellectual climate with that of the French Revolution. The issue was to prepare and suddenly decree the Terror. … We decided not to wait for 1793: the Terror right away, in ’89.”

Tzara and Picabia weren’t notified of the Grande Saison before it was announced publicly, and they reacted differently to the news. Picabia took it as a cue to distance himself from Dada entirely. Tzara was less willing to relinquish the Dada name, and so he energetically injected himself into the goings-on. If he couldn’t assume control of Dada’s new program, he would be sure to leave his mark on it. His contributions bordered on sabotage. Playing a witness at a mock trial that Breton and Aragon had initiated against the author Maurice Barrès, Tzara broke the proceedings’ solemn air with meandering fictions, a ditty about elevators, and—just before calling his fellow Dadaists bastards—a dismissal of the whole enterprise: “I haven’t any confidence in justice, even if this justice is done by Dada.” Within Breton’s attempts to “build instruments,” Tzara wedged a kernel of self-contradiction.

“Liquidation” emerges from the same contrary aims and fractious relations as the Grande Saison. Just take a look at Tzara’s scoring. Whereas other judges made an honest go at probing and quantifying their opinions, Tzara most frequently resorted to a scalding -25, an expression of disdain for both the authors and the exercise. The occasional Bach (2) or Trotsky (3) merited his lukewarm approval, but Tzara reserved his high score (12) for his fellow Dadaists (regardless of what personal enmities were simmering). A less overt act of sabotage came from Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, who assigned his scores according to chance. Despite such instances of recalcitrance, the scores and the list itself still yield insights into the historical avant-garde. For one, it registers the diminished regard for the star contributors to Littérature’s first issue two years prior, Gide (-0.81) and Valéry (1.09). Wildly oscillating scores level out to 0.45 for Maurice Barrès, the author whose dramatic transformation—from an anarchist aesthete Breton and Aragon greatly admired to an ultra-nationalist demagogue they detested—prompted the Grande Saison’s mock trial the following May. At that same trial, the Dadaist Benjamin Péret dressed in German military gear and claimed to be the Unknown Soldier (Soldat inconnu) buried in the World War I memorial at the Arc de Triomphe, stirring the audience to storm the stage and bellow “La Marseillaise.” A vivid symbol of nationalist fervor, the Unknown Soldier here receives -15.63.

Despite—or, indeed, because of—Dada’s poor regard for the mood in Paris, the list is overwhelmingly French, punctuated with only a few non-nationals. The paltry four English writers are Shakespeare (9.18), Lord Byron (-3.18), eighteenth-century poet Edward Young (3.18), and John Stuart Mill (a miserable -17.45), just slightly outnumbering their Irish neighbors, Jonathan Swift (11.09), John Synge (8.45), and Oscar Wilde (-1.45). There are a handful more Americans, mostly because the Dadaists were silent-film devotees: Fatty Arbuckle (5.72), Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. (-5.27), and William S. Hart (1.18). Also hailing from the US is Thomas Edison (4.00) who soundly thumps French scientist Louis Pasteur (-16.27) but is no match for Einstein (9.54). Jesus Christ (-1.54) runs neck-and-neck with Mohammed (-1.72). The Italian Renaissance suffers a beating—Michelangelo, Raphael, and Leonardo score -5.09, -10.72, and -9.00, respectively—as does the Italian Futurist Marinetti (-11.40). Englishman Charlie Chaplin (16.09), who appears only on the Les Premiers... list, stands third from the top—no surprise given his honorary Dada membership after Tzara’s Grand Palais hoax.

“Liquidation” also bears resemblance to the era’s highly unscientific newspaper reader surveys, of which the Dadaists were often a target. (Literally! From La Revue de l’époque: “Should the Dadaists be shot?”) Picabia (8.63) had recently been short-listed for La Merle Blanc’s “the most boring man in France” survey, a distinction he shared with Barrès and Charles Maurras (-14.90). Picabia refused to participate in “Liquidation,” and in his place sat his wife Gabrielle Buffet, the only judge who isn’t also rated, and the only woman anywhere on the chart other than the actress Jeanne Bourgeois, aka Mistinguett (-7.54), and the novelists Colette (-3.81) and Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont (3.54). Suspiciously absent is the writer Jean Cocteau, a friend of Tzara’s and Picabia’s, but anathema to Breton. “My opinion, completely disinterested, I swear,” Breton wrote Tzara in 1919, “is that he [Cocteau] is the most hateful person of our time.”

In short, “Liquidation” can and should be read from several perspectives. It’s a parody of publishing’s irrepressible urge to rate and register, an index of avant-garde opinion circa 1920, and a coded record of the affections and rivalries among a group of brilliant yet anxious young men. For those most interested in the latter angle, I heartily recommend Michel Sanouillet’s Dada in Paris, a cornerstone of Dada scholarship since 1965, finally translated into English this past year. It topped my list of the ten best books of 2009.

Colby Chamberlain is a Jacob K. Javits Fellow in the art history department at Columbia University and a senior editor for the online magazine Triple Canopy.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.