The Weather over Germany

Heinrich Böll’s literature of ruins

Declan Clarke

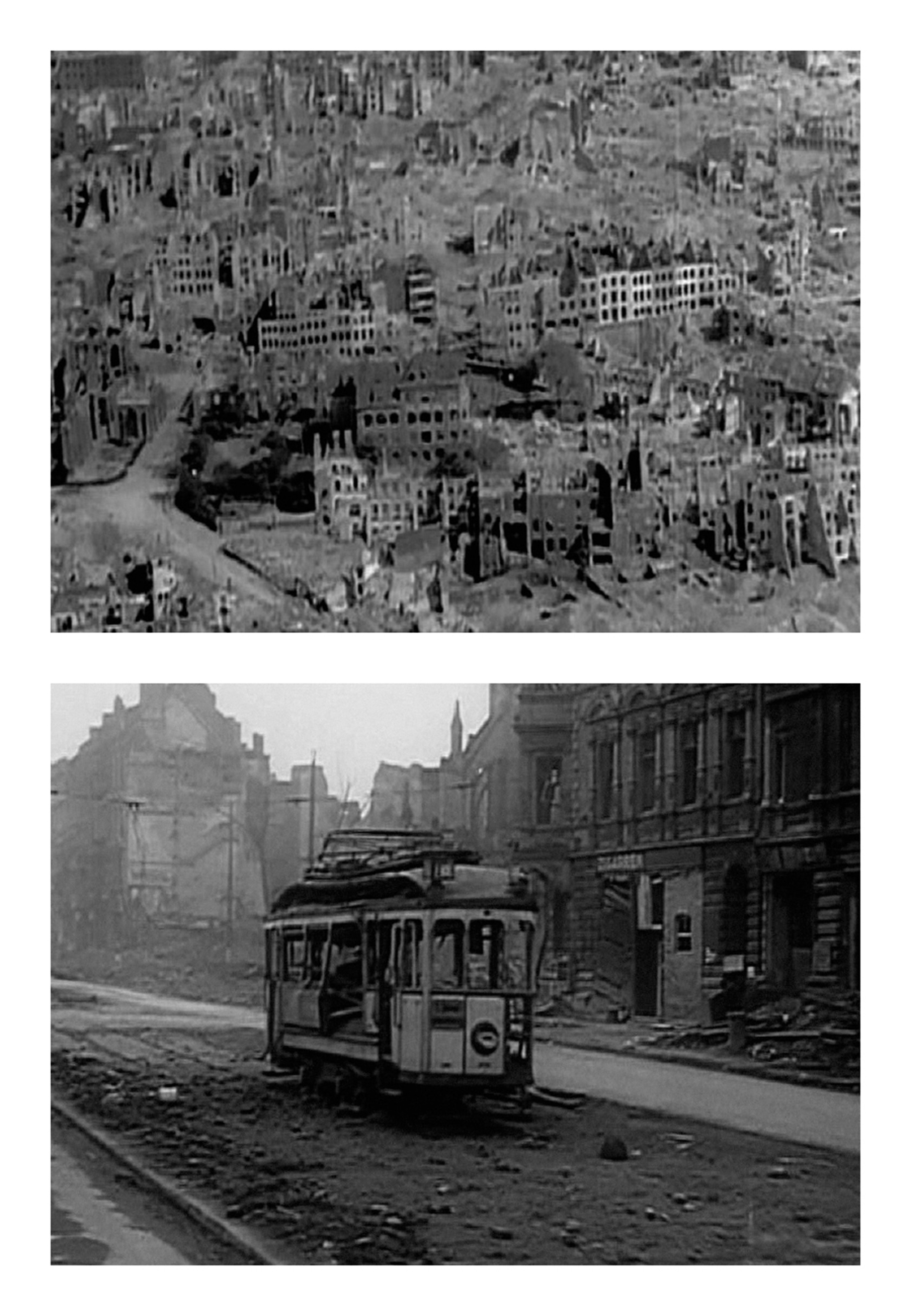

On the night of 30 May 1942, the last night of a full moon, poor weather conditions spared Hamburg the first ever Thousand Bomber Raid; the city would have to wait another 420 days. To identify a substitute, Arthur “Bomber” Harris—head of the bomber command of the Royal Air Force—surveyed the charts to find the largest possible target the weather over Germany would permit. He chose Cologne. Bomber crews reported that after the first hour they felt as if they were “flying over a spewing volcano.”[1] The following morning, the Kölner Zeitung wrote from their severely damaged offices that those “who survived the night and looked at the city the next morning were well aware that they would never again see their old Cologne.”[2] Two hundred and sixty-one air raids later, only five percent of the Old Town remained. By the end of the war, the population of Cologne had decreased from 770,000 to just 40,000, with 20,000 deaths attributed to the bombing campaign. The rest, rendered homeless, had fled.

Born in 1917, Heinrich Böll was conscripted into the Wehrmacht and fought in World War II. He served predominately in Eastern Europe and was wounded several times before being made a prisoner of war in 1945. An active opponent of Nazism, Böll returned after the war to his native Cologne to find seventy percent of the city’s buildings destroyed by Allied bombing (leaving behind 31.1 cubic meters of rubble per remaining inhabitant.)[3] He was deeply affected by this: though the duty of every returning soldier was to help clear the rubble from the streets, Böll refused to do so for reasons that he never explained.[4]

Becoming a professional writer in 1947, Böll became associated with the post-war German literature described as Trümmerliteratur—literally, the literature of the ruins. Ruins cast ominous shadows through much of his prolific output—most specifically in the posthumously published Der Engel Schweig (The Silent Angel), written in 1950 though not published until 1992. W.G. Sebald described the book as the most searingly accurate work of Trümmerliteratur, and went on to suggest that the rawness of the subject matter and the “irremediable gloom” with which it was told could have been the reason that the manuscript went unpublished in Böll’s lifetime.[5]

In the mid-1950s, Böll travelled to Ireland and was profoundly moved by the experience, finding that the country and its people reflected many of his ideals. He subsequently wrote a book entitled Irisches Tagebuch (translated as Irish Journal) that was published in 1957. Though not available in English until 1967, the book was hugely popular in Germany and is arguably still the most significant German publication on Ireland. In the immediate post-war era, when German nationals were viewed suspiciously by many of their European neighbors, the book prompted a huge wave of German tourism to Ireland and is still used as a selling point in German travel brochures.