Animals on Trial

Fora and fauna

Jeffrey Kastner

Man is the only animal that blushes. Or needs to.

—Mark Twain

In the image, the crowd is thick around the gallows. Townspeople fill the foreground of the medieval view; some turned toward their neighbors in conversation, most focused on a raised platform in the middle distance and the three figures arrayed on it. At the left edge of the group stands an official of some sort—a prelate reciting the last rites for the condemned perhaps, or an officer of the court, reading out the charges. At right, the hunched and hooded shape of the executioner looms, knee bent and back arched as he sets to his task. And in the middle, the star of the entire scenario (and the narrative it illustrates): the doomed head thrown back in terminal agony; the mouth a thin frowning spasm beneath a blunt nose. A really blunt nose. A pig’s nose, actually—a sow’s, to be exact—attached to a porker that inexplicably seems to be sporting a man’s shirt.

The scene comes to us courtesy the frontispiece engraving for an oddball gem of social history, The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals. Written by Edward Payson Evans and drawn from a pair of articles he originally published in The Atlantic Monthly in 1884—“Bugs and Beasts before the Law” and “Modern and Mediæval Punishment”—the text (revised and expanded, utilizing both historical and contemporary research by other scholars) was first brought out in book form in 1906.[1] A remarkably detailed piece of research and interpretation, Evans’s volume includes dozens and dozens of documented proceedings brought against animals by either governmental or religious bodies—from his earliest citation, discovered in something called the Annales Ecclesiatici Francorum, noting the prosecution of a number of moles in the Valle D’Aosta in the year 824 to the charges lodged against a cow by the Parliament of Paris in 1546 to the 20th-century conviction of a Swiss dog for murder, reported in the New York Herald the same year the book came out.

The history of animals in the legal system sketched by Evans is rich and resonant; it provokes profound questions about the evolution of jurisprudential procedure, social and religious organization and notions of culpability and punishment, and fundamental philosophical questions regarding the place of man within the natural order. In Evans’s narrative, all creatures great and small have their moment before the bench. Grasshoppers and mice; flies and caterpillars; roosters, weevils, sheep, horses, turtle doves—each takes its turn in the dock, in many cases represented by counsel; each meets a fate in accordance with precedent, delivered by a duly appointed official.[2] Yet for all the import (both practical and metaphysical) of the issues on which they touch, in their details the tales Evans spins often seem to suggest nothing so much as a series of lost Monty Python sketches—from the story of the distinguished 16th-century French jurist Bartholomew Chassenée, who was said to have made his not inconsiderable reputation for creative argument and persistent advocacy on the strength of his representation of “some rats, which had been put on trial before the ecclesiastical court of Autun on the charge of having feloniously eaten up and wantonly destroyed the barley crop of that province,”[3] to the 1750 trial in Vanvres of a “she-ass, taken in the act of coition” with one Jacques Ferron. In the latter case, the unfortunate quadruped was sentenced to death along with her seducer and appeared headed for the gallows until a last minute reprieve was issued on behalf of the parish priest and citizenry of the village, who had “signed a certificate stating that they had known the said she-ass for four years, and that she had always shown herself to be virtuous and well-behaved both at home and abroad and had never given occasion of scandal to anyone…” Nudge, nudge; say no more.

Other less elaborated details also emerge from Evans’s extensive tabulation of the dates, locations, and defendants in various trials featuring non-human participants, made into a long list that appears among the book’s many appendices.[4] Its breadth, though said by the author to undoubtedly be incomplete, is awesome; its “ye olde” timeframe and quaintly exotic Continental locales (predominantly in Germany, France and Switzerland, but also extending to the British Isles, North and South America, Scandinavia, Russia and other areas) and often improbable casts (e.g. the “Cow, two Heifers, three sheep, and two Sows” on trial in one 1662 case) will have many contemporary readers filling in the numerous factual gaps with narrative scenarios that are equal parts Breughel and Gary Larson. What, for example, could have possibly inspired the judiciary of Marseilles to bring proceedings against a group of dolphins in 1596? How exactly did medieval Lausanne come to be so astonishingly pest-ridden? (Documents from the Swiss city record separate prosecutions of eels, worms, rats, numerous groups of vermin, and several collections of bloodsuckers between the 12th and 16th centuries on the shores of Lac Léman, after which things seem to have taken a turn for the better). And just what might have driven a lone goat to get mixed up with sixteen bovine troublemakers in the nefarious enterprise that brought them all before the court in the town of Rouvre in 1452? (Or was it, perhaps, the goat that was the mastermind, having enlisted the slow and trusting cows as the muscle behind some scheme?)[5]

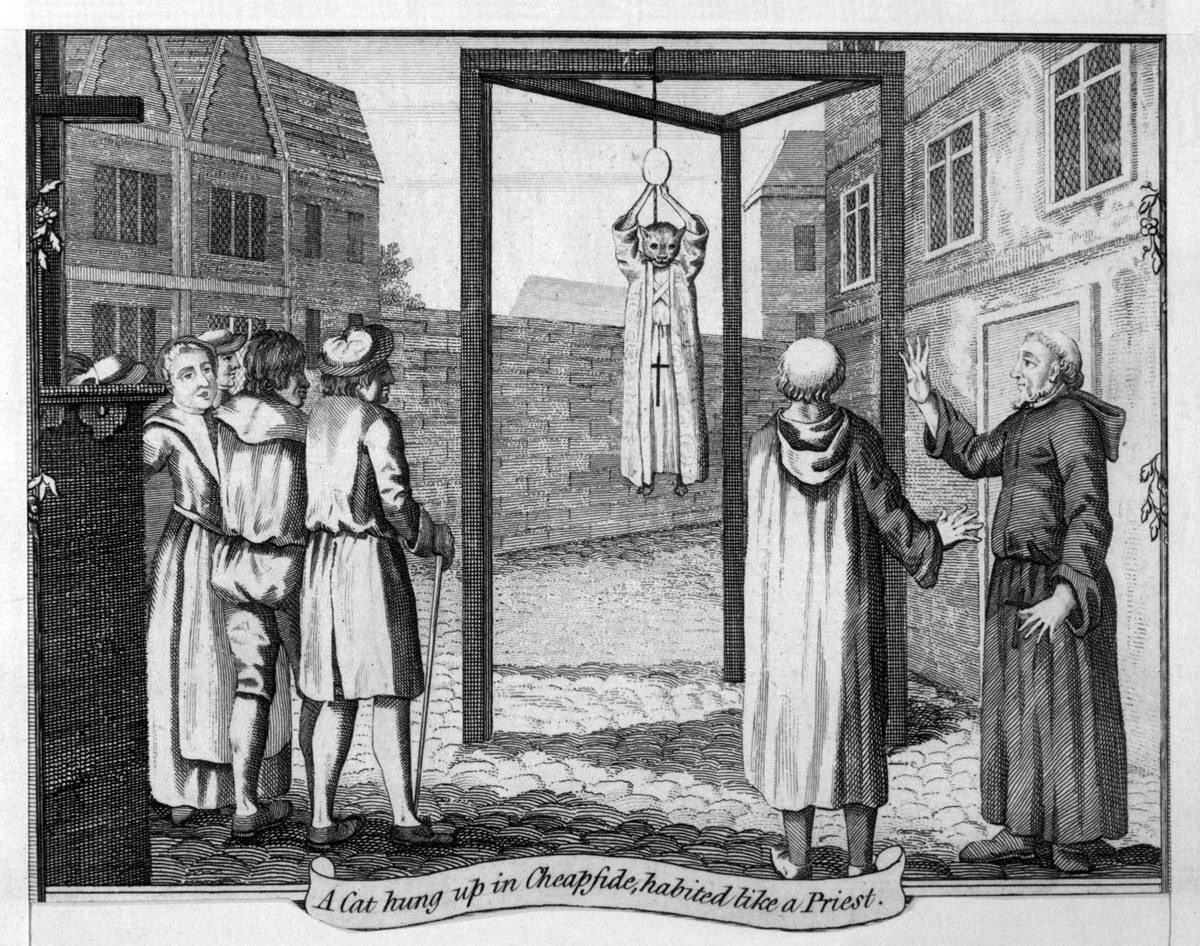

Of all the various and sundry beasts that populate Evans’s narrative and his tables, none appears so frequently as the pig; the author connects the freedom of movement generally afforded porkers in medieval towns and villages to the disproportionate number of them that seem to have run afoul of the authorities. The book is peppered with accounts of swine being punished for various improprieties (often vicious attacks against infants),[6] including the one that the frontispiece engraving is meant to depict— a particular 14th-century execution, carried out against an infanticidal sow in the Norman village of Falaise. Evans actually gives us more on this one than usual. “In 1386,” he writes, “the tribunal of Falaise sentenced a sow to be mangled and maimed in the head and forelegs, and then to be hanged, for having torn the face and arms of a child and thus caused his death…. [T]he sow was dressed in men’s clothes and executed on the public square near the city hall at the expense to the state of ten sous and ten deniers, besides a pair of gloves to the hangman.” Evans includes the language of the executioner’s original receipt in one of the appendices and, in the main text, angrily denounces the whole event as a “travesty of justice” that relies on the “strict application of the lex talionis, the primitive retributive principle of taking an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth,” although it’s not completely clear what exactly makes the sentence meted out in Falaise any more or less ignoble than his other examples.[7] So the facts of that fateful winter day in Falaise seem clear. As for the image of it that has come down to us, however, much remains in doubt—a kind of doubt that both plagues and enriches not just the rare visual illustrations of these kind of historical activities, but the whole constellation of information on which such history is built. The engraving in the Evans book is obviously not from the time of the trial. What it actually turns out to be is a 19th-century “reconstruction,” published in a French picturebook, of a long-since destroyed fresco in Falaise’s Church of the Holy Trinity. Now, this fresco supposedly commemorated the execution, but was never copied while it was extant and so the modern illustration, says Evans, was based on numerous descriptions of it by various writers of the time. (No information is provided about the date of the fresco’s original creation, but it is probably safe to assume that it was quite a bit later than the 1380s. And so it was itself a non-contemporaneous depiction—in its case, not of an image but of an event—presumably based on a mix of documentation, oral history, and legend.) At any rate, the whole thing was apparently painted over in the 1820s and then further hidden behind a piece of interior construction, and so had been effectively lost for more than half a century when it was reproduced in the version we now have, which itself came into being roughly five hundred years after the event it purports to document. In short, it provides a ready example of the fogbank in which this type of material tends to reside—the gray area between fact and imagination where, for contemporary lay observers anyway, it becomes almost impossible to distinguish between actual historical detail and the flotsam of cultural memory deformed by fairy tale medievalism and a parade of anthropomorphized cartoon animals.[8]

Whatever one makes of the big-picture judicial and theological implications of animal prosecutions—and there’s obviously no lack of ways to go with that—as sociocultural phenomena they do seem to make a kind of weird sense. They’re at once unimaginable and eminently imaginable, feeding and feeding off of our complicated relations with animals and the way these relations have found their way into our myths and legends and stories; the part they’ve played in the development of our cultural and social identity. Science has given us (with the exception, perhaps, of a few counties in Kansas) a feeling of certitude about what kinds of things we might share with animals biologically and environmentally. It has not, however, done much to assuage the deep, atavistic sense that for all its familiar ease, there is something slightly odd about our contact with other creatures, a lingering ambivalence into which these kinds of historical memories still neatly plug.

The ritual environments of the trials Evans and others describe no doubt functioned as complex symbolic matrices through which developing modern society worked out its uncertainties about the place of man and beast before God (or was it god and beast before Man?), that is to say, its constituents’ uncertainties about themselves, about the creatures with which they shared their existence, and about the chaos that buffeted all of them. The assent of the public gave such rituals their power and, in turn, the rituals gave the public assurance, a semblance of order, a tangible example of both human power and humane discretion. If religion provided society with certain transcendental truths, social systems terrestrialized these truths, took a shot at putting the Word into deed. History has kept a record of both—a record warped, enhanced, and endlessly mitigated by memory and subjectivity and uncertainty, but one that nevertheless continues to convey our lasting fascinations and fears across the centuries. One some level, all of this is obviously just strong animals killing weaker ones—humans and non-humans each playing out their evolutionary roles. What separates the phenomenon from your everyday food-chain behavior is the ritual it involves, and the way those rituals acquire meaning in their retelling, find shape in words and images.

There was a week or so when we here at Cabinet were trying to find a copy of the frontispiece engraving so we could reproduce it along with this article. But at some point it started to seem like it might be best to leave the image, like the specific story it illustrates and the general kind of history it epitomizes, in the memory space where it already resides, open to further layers of retelling, available to yet more speculation. So before it gets painted over again in the mind’s eye, a last glance—at the sow choking in her garrote and at the faces that surround her, vengeful and empathetic, appalled and fascinated. Animal, too, and too human.

- The Criminal Prosecution and Capital Punishment of Animals was first published in the United States by E. P. Dutton and has been reprinted several times, including a 1988 edition brought out by Faber and Faber in London and, a decade later, in a facsimile published by The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd., of Union, New Jersey. Of the few recent commentaries to reference it, most notable is “Rats, Pigs, and Statues on Trial: The Creation of Cultural Narratives in the Prosecution of Animals and Inanimate Objects” a very smart and expansive treatment in the May 1994 issue (Vol. 69, No. 2) of the New York University Law Review by Paul Schiff Berman. Berman’s article relies heavily on Evans—and also makes impressive connections in related source material ranging from St Thomas Aquinas, who treated the subject in his Summa Theologiæ to Racine’s 1668 play Les Plaideurs, which satirizes animal trials, to the contemporary British novelist Julian Barnes, who incorporates the phenomenon into his A History of the World in 10 Chapters. This piece is similarly indebted to Berman’s research, and his insights into the social and jurisprudential contexts surrounding the issues. And, yes, it does say statues: Berman describes an Athenian court of law housed in a building on the Acropolis called the Pryteneion which was, according to commentators including Aristotle, dedicated to the prosecution of “inanimate things and animals” in addition to unknown assailants. But this, needless to say, opens another can of worms entirely.

- Evans addresses two major types of trial forms. In civilian courts, large animals were typically tried as individuals or in groups for specific instances of misbehavior. In ecclesiastical tribunals, large communities of smaller animals (rats, mice, bugs, etc.) were tried symbolically; the sentences (curses, excommunication, anathemas) were obviously designed not to penalize particular animals but to symbolically call down divine retributions upon entire classes of creatures.

- During the trial, which occurred at the beginning of the 16th century, Chassenée first argued that the summons issued for the rodents’ appearance was not disseminated widely enough to reach the more far-flung members of the population. Then the barrister claimed that although they had been duly notified (the court by then having issued a second summons, which it had read from the pulpit of each parish in which the offending rats dwelled), the failure of his clients to appear before the prelate was not due to a lack of respect for the court. Instead it was a result, as Evans explains it, of “the length and difficulty of the journey and the serious perils which attended it, owing to the unwearied vigilance of their mortal enemies, the cats, who watched all their movements, and, with fell intent, lay in wait for them at every corner and passage.” Chassenée lost the case, but the event apparently had a profound impact on the lawyer’s career, sparking an interest in the issue that he pursued at greater length in a 1531 treatise, which Evans discusses in depth.

- Along with a bibliography and the tables, Evans’s appendices also include the original text of a number of period documents describing various prosecutions, excommunications, and executions.

- For all their wonders, Evans asserts that his tables are limited only to authentic, documentable cases of animal prosecutions that ended in guilty verdicts. “A few early instances of excommunication and malediction,” he writes with his typical flair for the resonant oddity, “our knowledge of which is derived chiefly from hagiologies and other legendary sources, are not included in the present list, such, for example, as the cursing and burning of storks at Avignon by St. Agricola in 666, and the expulsion of venomous reptiles from the island Reichenau in 728 by Saint Perminius.”

- The shortlist of these, at least for their value as curiosities, must include the hanging of a pig at Mortaign in 1394 for having eaten a consecrated communion wafer. Evans also cites the undated trial of an infanticidal pig that ate the flesh of a child on a Friday and thus contravened the Catholic Church’s jejunium sextæ, a fact that was accepted by the court as an aggravating circumstance surrounding the crime. And then there is the prominent 1379 trial in which three sows were convicted of murder for trampling the son of a swineherd near the Burgundian town of Saint-Marcel-le-Jeussey. As Evans reports, “[T]wo herds of swine, one belonging to the commune and the other to the priory of Saint-Marcel-le-Jeussey, were feeding together near that town, [when] three sows of the communal herd, excited and enraged by the squealing of one of the porklings, rushed upon Perrinot Muet, the son of the swinekeeper, and before his father could come to his rescue, threw him to the ground and so severely injured him that he died soon afterwards. The three sows, after due process of law, were condemned to death; and as both the herds had hastened to the scene of the murder and by their cries and aggressive actions showed that they approved of the assault, and were ready and even eager to become participes criminis, they were arrested as accomplices and sentenced by the court to suffer the same penalty. But the prior Friar Humbert de Poutiers, not willing to endure the loss of his swine, sent an humble petition to Philip the Bold, then Duke of Burgundy, praying that both the herds, with the exception of the three sows actually guilty of the murder, might receive a full and free pardon. The Duke lent a gracious ear to this supplication and ordered that the punishment should be remitted and the swine released.”

- One wonders if it might be the costuming of the pig that so troubles Evans, although he does not seem all that bothered by the other examples he cites of the practice of dressing animals in human clothes for their trial or execution, a phenomenon that reaches its creepy zenith in a bizarre account he furnishes of a 1685 trial in Ansbach, Germany, of what is referred to as “were-wolf.” In that case, the animal, “supposed to be the incarnation of a deceased burgomaster of Ansbach, did much harm in the neighborhood of that city, preying upon the herds and even devouring women and children. With great difficulty the ravenous beast was finally killed; its carcass was then clad in a tight suit of flesh-coloured cere-cloth, resembling in tint the human skin, and adorned with a chestnut brown wig and a long whitish beard; the snout of the beast was cut off and a mask of the burgomaster’s features substituted for it, and the counterfeit presentment thus produced was hanged by order of the court.” According to Evans, this bit of startlingly macabre taxidermy was subsequently preserved in a cabinet of curiosities to memorialize the event.

- The week this essay was started, the two highest-grossing movies in the US were Shrek, which stars an ogre, a prince, a dragon and a talking donkey, and A Knight’s Tale, a love story set in the milieu of medieval jousting tournaments.

Jeffrey Kastner is a New York–based writer and an editor of Cabinet.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.