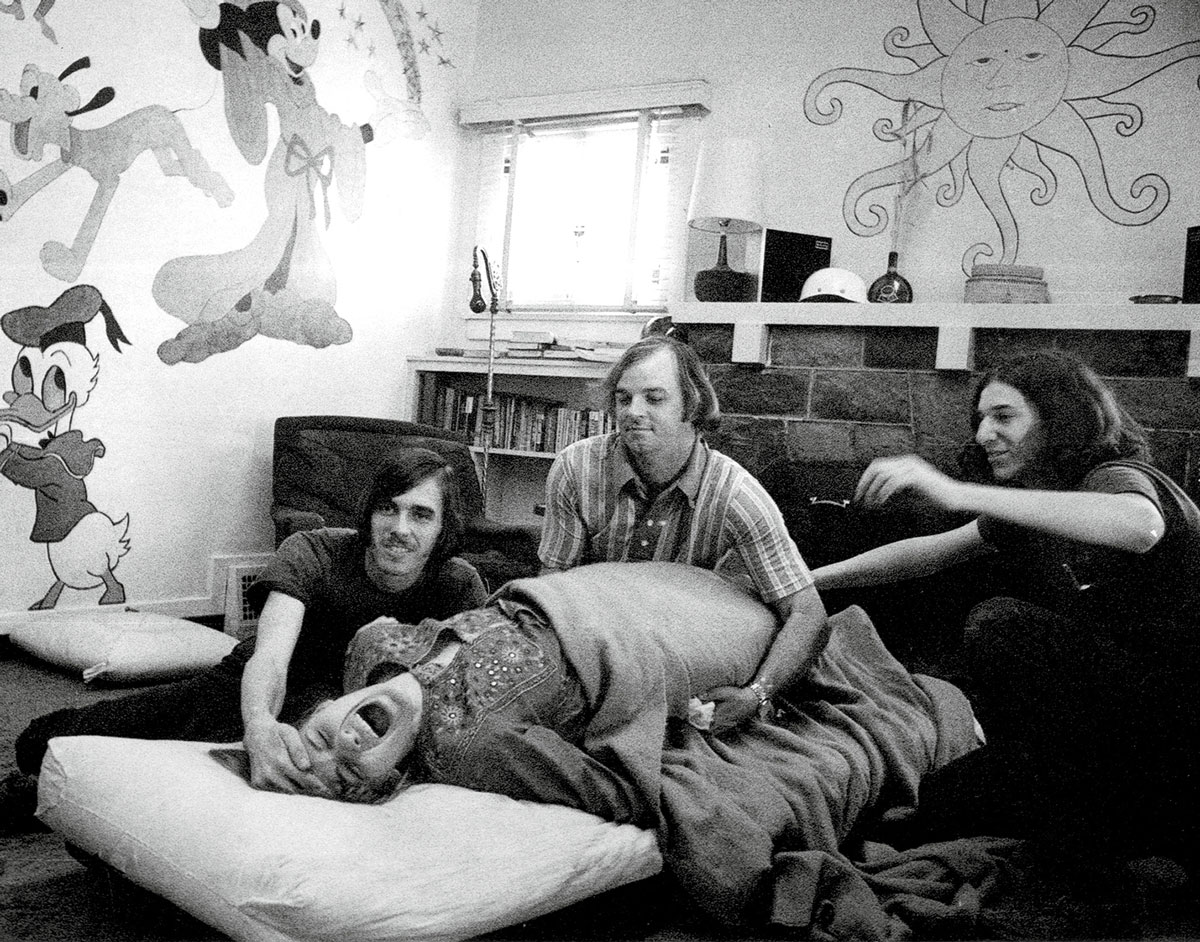

Legend / Restraint

Muscular arms, wristwatch, moustache

Wayne Koestenbaum

“Legend” is a column by Wayne Koestenbaum in which he suggests one or more possible captions for an image provided by the editors of Cabinet.

Art requires restraint. Too much emotion, too many liberties taken, and the work falls apart.

The artist alone can’t supply the restraint. Outside forms must save the artist from the peril of excessive emotion.

The artist, if lucky, has friends—severe friends, who can corral the artist’s wayward instincts and provide closure, symmetry, irony.

Without restraint, an artist might fall into the bathetic, the regressive; without restraint, the artist might return to the sad level of a Donald Duck, a Mickey Mouse, a Pluto.

Baudelaire nearly outgrew the alexandrine; he fought against it. But the alexandrine won. The alexandrine tied Baudelaire to his bed. Baudelaire screamed. Baudelaire’s spine arched. Baudelaire remembered visiting the Salpêtrière; he remembered the florid antics of the ill and the mad. Baudelaire begged the alexandrine, “Have mercy!” Baudelaire, like a lesbian, or a sphinx, or a legendary beauty in her palace, smiled, his mouth open, teeth flashing, tongue glistening, like the voluptuous furniture, polished by the years, surrounding him.

Micky Dolenz, lead vocalist in the Monkees, also knew restraint, and reaped rewards from it. Without the restraint of a song’s form, how could “Randy Scouse Git” have been born? The same goes for “Going Down,” or “Regional Girl.” Without the restraints—temporal, syntactic, stylistic—of a pop song’s armature, how could “Shorty Blackwell” have hit the big time?

Micky Dolenz’s cuteness, too, blossomed under the harsh sign of Restraint. If Micky Dolenz had relaxed into the randomly effeminate or the chunkily pugilistic, his aesthetic appeal would never have risen like a burning comet in TV’s azure. Because of situation comedy’s restraints, and because of the limits that Masculinity, as a sign system, imposed on his behavior, Micky was able to achieve a cuteness that we can only compare to Baudelaire’s use of the sonnet form; though it is doubtful that a poem like “La Beauté” (“Je suis belle, ô mortels! comme un rêve de pierre”) physically stimulates its readers, the effect of its closely spaced rhymes and rigidly limited lexicon on the limbic system has much in common with the arousing effect that Micky’s body, in its prime, produced in the teen spectator.

If restraints did not exist in art, we would not have Jeff Koons’s photographs of himself in sexual intercourse with his then-wife Cicciolina, an Italian porn star. Only the conventions of photography, as a medium blessed with restraint, allowed these images to attain parturition. We could say, courting pomposity, that restraint allowed Jeff Koons’s erect penis, whether simulated or real, to cross the proscenium of art, to leave behind the childish world of experience, and to enter representation, with its salutary illusions, codes, abrasions, and liqueurs.

Therefore, too, we are in the position of thanking restraint for its brute force. We thank restraint for its muscular arms, its wristwatch, its moustache; we thank restraint for its unventilated parlor, its lack of deodorant, its athlete’s foot, its dandruff; we thank restraint for its unclipped fingernails, its dirty kleenexes, its dingleberries. To restraint, we bow down; we lick the soles of restraint’s brogues.

Wayne Koestenbaum is a Distinguished Professor at the CUNY Graduate Center in New York. He has published twelve books of poetry, criticism, and fiction, including, most recently, Hotel Theory (Soft Skull, 2007) and Best-Selling Jewish Porn Films (Turtle Point Press, 2006).

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.