Tragic Candy, Time

Eating Minou Drouet

Carol Mavor

It is never a good thing to speak against a little girl.

—Roland Barthes, “Myth Today”

In France and America, a girl sensation is erupting. The public has fallen in love with girls who are roughly 4,562.5 days old (12.5 years). And, for those less Humbert-Humbertish, there are child-women who are older, but somehow not. (Was Brigitte Bardot really so naive as to believe at age eighteen that mice laid eggs?)

“A breeze from Wonderland is in the air.”[2] Girls are everywhere, not only in films, but also as authors. Just three years before, in 1954, the aggressive publisher René Julliard scored an international triumph with Françoise Sagan’s Bonjour Tristesse. Sagan was eighteen years old. (By 1957, the childish, boyish, sexy Jean Seberg will star in the film adaptation of Bonjour Tristesse.)

Just a year earlier, in 1956, Vladmir Nabokov had published Lolita and B.B. (Brigitte Bardot) found herself to be an American sensation for her role in And God Created Woman, where she childishly ate and made love with the “same unceremonious simplicity.”[3] While the always-barefoot B.B. was preserving the “limpidity” of childhood and its “mystery,”[4] the aggressive Julliard scored again. After the success of Bonjour Tristesse, he snatched up the child-poet Minou Drouet and published her first book of poetry: Arbre, mon ami (Tree, My Friend). Drouet was only eight years old.

The familiar myth of the child (as innocent and as artistic genius) was ripened by Drouet. As James Kincaid has carefully schooled us: “We construct an emptiness, a child, and set it to dreaming.”[5] Paradoxically, the empty innocence of Drouet (as the photographs proclaim) is sexual. Paradox, however, is not a contradiction: it is a rhetorical strategy, an artistic treatment of a logical problem. Myth itself, thereby, is a paradox: it cloaks truth in fiction and fiction in truth, as if it were a little girl.

The child is a studied myth; the girl is its most pure form.

In “Myth Today” (Mythologies’ concluding essay), Barthes claims with witty Saussurean irony that this Lottelita, this Lolitchen, (think Nabokov and Werther), this poetess named Drouet, had her own system of signs. As Barthes explains with the clinical disinterest of a scholar-man who likes boys, not girls: “A tree is a tree. Yes, of course. But a tree as expressed by Minou Drouet is no longer quite a tree, it is a tree which is decorated, adapted to a certain type of consumption, laden with literary self-indulgence, revolt, images, in short with a type of social usage which is added to pure matter.”[6] Barthes’s “semioclasm”[7] is out to destroy the “myth of Childhood-as-poet.”[8]

In the French publication of Mythologies, the poetess gets an entire essay: “Literature According to Minou Drouet.” There, Barthes further unveils Drouet’s “nymphancy” as inseparable from her poetry.[9] But the little treatise was axed in 1972, when the book was translated into English. The famed Drouet had already been forgotten.

Today, as Robert Gottlieb notes, few people (especially those under a certain age) know much about Drouet, even in Paris. Was she a “victim” of her publisher? Did Cocteau say something “bitchy” about her?[10]

Who is Minou Drouet?

Today, she is Mme. Jean-Paul Le Canu. She is in her sixties. She lives in hibernation in her childhood home, under the shadow of the big cedar tree that she has always loved. It seems that she, too, has chosen to forget “la petite princesse des mots” (the little princess of words).[11]

crystal cage

…

siamese animal twin of my heart,

greedy eyes like children’s eyes

who looking at pastries

undress the icing

from cakes all crackly with frost

mouth which nibbles with no respite

this tragic candy, time.

—Minou Drouet, “The Watch”

Once upon a time, in Brittany, Minou was born (1947). Minou means kitten (more accurately “pussy”) in French. Her father was a very poor field hand. Many said that her mother was a prostitute. As we all know, in real life and in fairy tales, “daughters wander off into the woods, stumble into prostitution, fall in love with sailors, are eaten by wolves.”[12] It was not such a promising beginning. But when she was a year-and-a-half old, a worrisome fairy godmother (and aspiring poetess) named Mme. Drouet adopted quiet, barely mewing Minou.

By age six, little Minou still had not spoken a word. She was tight-lipped and silent. Minou was Briar Rose waiting to be awakened. “Waiting is an enchantment.”[13] (“Enfant. From the Latin infans; from in (not) and fari (to speak): the one who does not speak.”[14])

“One day, her mother played a recording of a Brahms symphony for her. Minou swooned. When she was revived, she spoke perfect French in complex sentences. Shortly thereafter she began to write poetry.”[15]

Minou had become enchanted.

Minou had become enchanting.

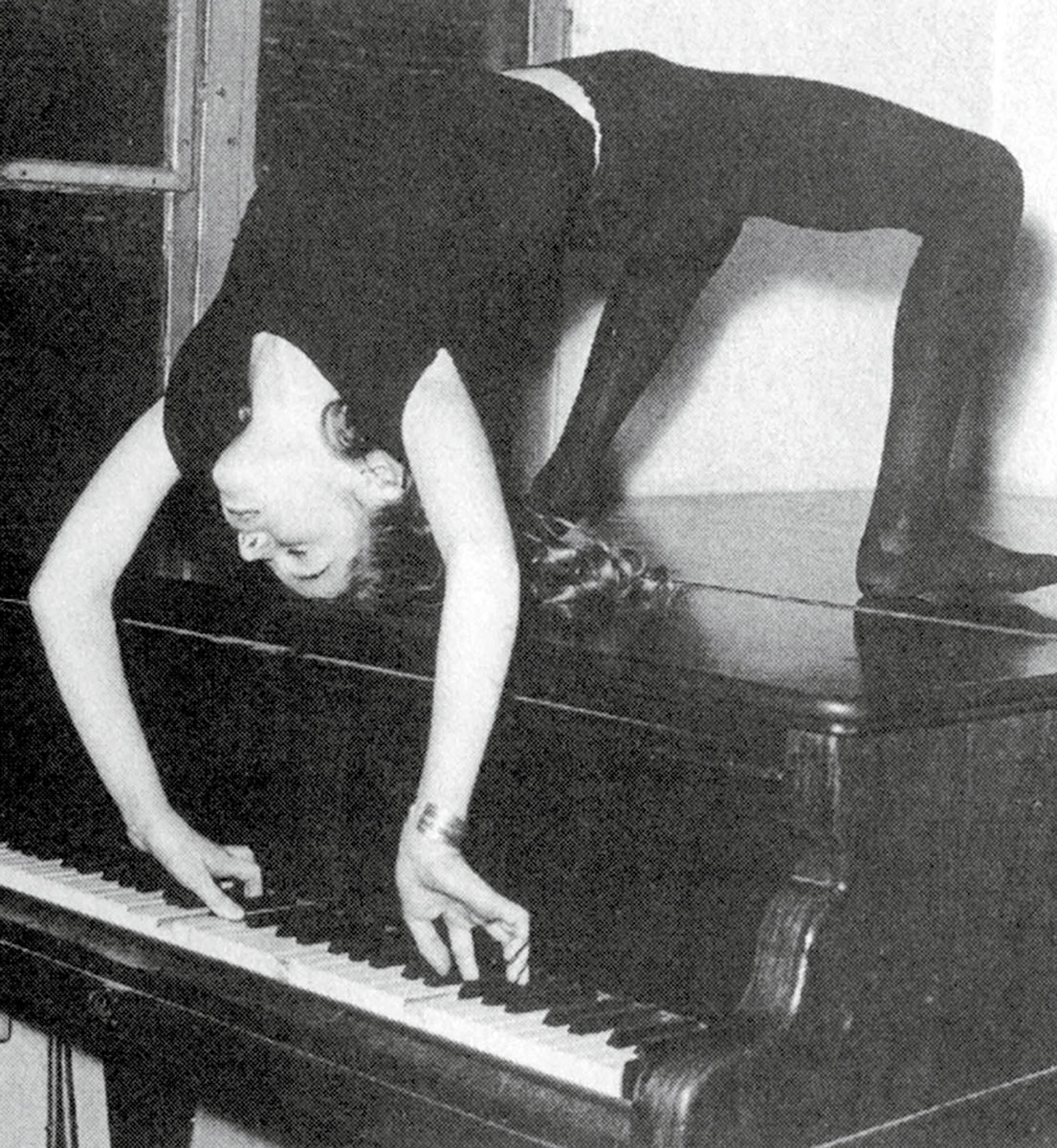

As in many fairy tales, Maman was the wicked stepmother. Mme. Drouet cracked the whip: ballet lessons, guitar lessons, hours of piano practice and gymnastics, “every minute accounted for.”[16] Even though she could play Mozart while doing a backbend on the piano, Minou could never be perfect enough; one might even say “empty” enough. (“Innocence is … like air … there’s not a lot you can do but lose it.”[17]) Mme. Drouet beat the innocence (air) out of Minou for the most miniscule mistakes.

In a letter to the famous pianist Yves Nat, Minou complains:

Little girls’ bottoms are really a wonderful gift from heaven for calming the nerves of mothers. I know perfectly well that’s what they were invented for, for hands have hollows and bottoms have humps. It’s because of you that I had my bottom spanked, because I didn’t write Mr. in the address and didn’t put a capital letter.[18]

Minou’s letter smacks of Eve Kosofksy Sedgwick’s girlhood poetry under the rap of spanking. As Sedgwick writes in her 1987 startling retelling of Freud’s “A Child Is Being Beaten” as “A Poem is Being Written”: “When I was a little child the two most rhythmic things that happened to me were spanking and poetry.”[19] Sedgwick confesses that, as a girl, she took sexual pleasure in writing poetry with plenty enjambment to the eroticized beat of being spanked. (But for Sedgwick the results were much different.)

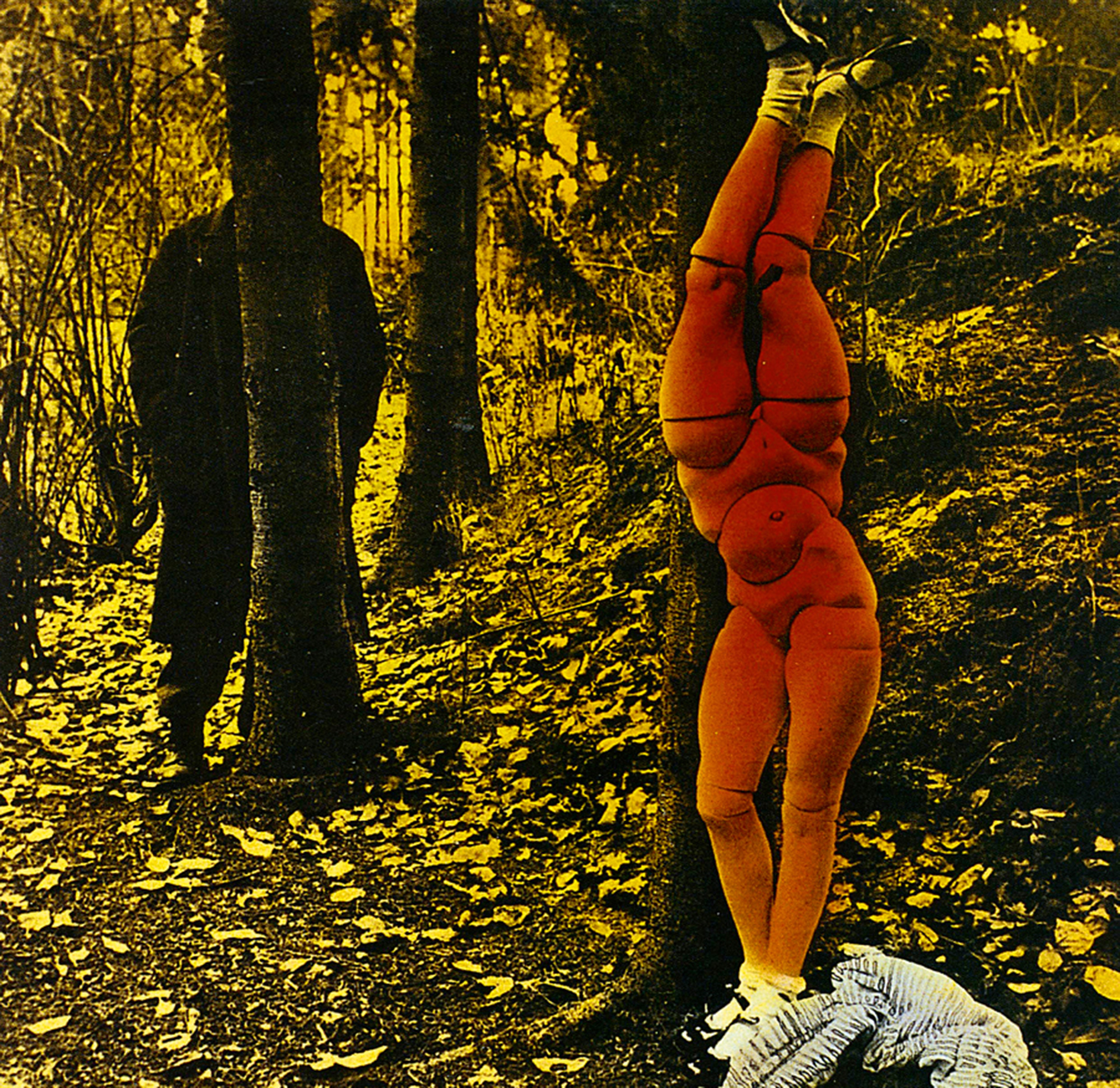

In the same letter, Minou speaks of “angry trees which seem to be kicking at the sky, trees through which something so gentle was passing.”[20] Minou’s words are strangely in accord with Hans Bellmer’s 1935 photograph of Drouetish legs kicking their Mary Janes and bobby socks up into the trees.[21] The poupée legs (those standing and those kicking) are in bondage with, and/or in love with, these trees that grow in likeness with them. A shadowed figure lurks.

A strange and troubled child, Minou was odd. Minou did not fit in. As she writes in “Photograph,” “I brought you nothing / but an ugly face / a nose for telephoning to the clouds….”[22] Minou found solace in the tree that she loved, her true friend, who lived (and still does) in her garden in la Guerche de Bretagne, “a very big cedar of Lebanon.”[23]

Tree that I love,

tree in my likeness,

so heavy with music

under the wind’s fingers

that turn your pages

like a fairy tale,

tree …[24]

Remember what Barthes says in “Myth Today”: “A tree is a tree. Yes of course. But a tree as expressed by Minou Drouet is no longer quite a tree.”[25]

It was in 1955, when some of Minou’s poems and letters were privately circulated among French writers and publishers, that what Julliard called a “minor Dreyfus Affair” began. Almost overnight, there were appearances on television and articles in magazines and newspapers. People took sides. Did she write the poems or not? Minou became a French and American sensation. Minou was photographed by Elle, Life, Time, and Paris Match: at her desk with her pen in hand, with her teddy bear, with her adoptive mother and cat, and almost always with that giant Drouet bow. (The bow is not only Bellmer’s metonymy, it is also Minou’s.)

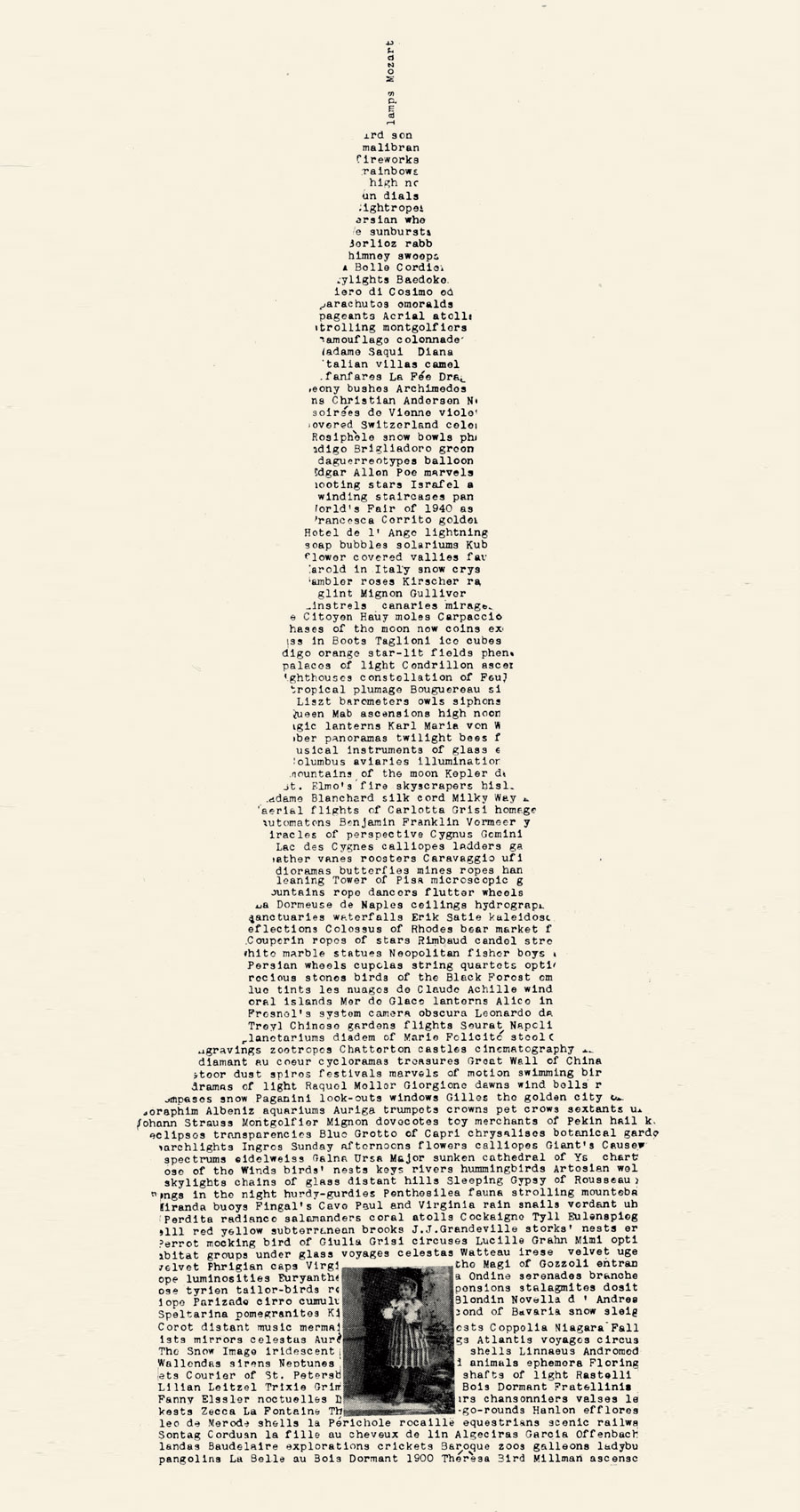

On 20 January 1956, a test was organized by the Société des Auteurs (SACEM) to discover the truth: “Minou was placed in a room behind one-way glass.”[27] She was told she could write on “I am Eight Years Old” or “Paris Sky.” Since, as she claimed, her “eight years were already too sad,” she chose “Paris Sky.”[28] Within twenty-eight minutes she wrote “Ciel de Paris.” It was written in the shape of Minou’s beloved tree; like Apollinaire, she liked to make her poems into calligrammes, serpentine shapes, crystal cages of words.

Paris Sky,

weight,

secret,

flesh,

who by hiccups,

spits in our faces

through the open maw of rows of houses

a spurt of blood

between its luminous stumps of bad teeth …[29]

Drouet is Shirley Temple on the good ship lollipop: swallowed by the mouth that hiccups and “spits in our faces” the myths of little girls as sugar and spice and everything nice. Drouet is Berenice trapped in Joseph Cornell’s 1943 The Crystal Cage, like jelly in the sugary doughnuts that he childishly loved.

The SACEM test was a modern-day fairy tale: Drouet was Snow White in a glass box (coffin). Would she feel the pea under the pile of mattresses? Would her foot easily slip into the glass slipper?[30] As Barthes notes: it was “a detective story: did she do it or didn’t she?”[31] (Fairy tales are always detective stories: they sort out real princesses from imposters.)

In the end, she won. She was awarded membership.

—Brothers Grimm, “Little Red Cap”

My only grudge against nature was that I could not turn my Lolita inside out and apply voracious lips to her young matrix, her unknown heart, her nacreous liver, the sea-grapes of her lungs, her comely twin kidneys.

—Vladimir Nabokov, Lolita

I must be a little rabbit who once turned its fur inside out for fear of moths.

—Minou Drouet, extract from a notebook

As markers of lost time, photographs are always-already tragic, deadly murderers of life once lived, perhaps especially if they are picturing a sweet little girl like Drouet. The camera is a killing “mouth which nibbles with no respite / this tragic candy, time.”[32] Likewise, in Camera Lucida, Barthes glazes the photograph as sugar housed in the violence that originally bespoke the fairy tale:

The Photograph is violent: not because it shows violent things, but because on each occasion it fills the sight by force, and because in it nothing can be refused or transformed (that we can sometimes call it mild does not contradict its violence: many say that sugar is mild, but to me sugar is violent, and I call it so).[33]

The photograph, then, is brutal not only like sugar, but also like Perrault’s original fairy tales, in which the eyes of Cinderella’s sisters are pecked out and Hansel and Gretel are almost eaten.

The large letter O, which begins fairy tales with great ornamental flurry, is derived from the Egyptian hieroglyph for the eye: both the iris and the pupil are circles. Yet an O is also an open mouth. The eye and the mouth ingest as figures of oralia.[34] (O is also for oralia.) While oralia emphasizes the double consumption of the mouth as eye, it is also a variant of the Latin aurelia, which means “golden.” When Bellmer (in another doll photograph, this one from 1934) places a headless poupée on a large letter O crowned with a bow, with her eye spit back onto her footless ankle, the emptiness of the child is perversely set to dreaming. It is the start of a surreal Once-upon-a-time tale that is not so far from the (un)golden childhood that was lived by Minou.

Barthes does not like “Drouetist poetry.”[35] It is “docile, sugary poetry,”[36] “stuffed” with “formulas.”[37] According to Barthes, Drouet fulfills a cultural desire to demote and to tame literature into a sweet nothing.

As Richard Howard notes: “In the central range of French language, there is no word for child … If there have been children in French Literature, they are there as mere instances of acculturation; as victims (Hugo, Renard), as cult objects (Hugo again, Gide); either assimilated by Society as in infants (speechless) or transformed into members (remembered) or extruded as freaks (Minou Drouet).”[38]

As Barthes writes: “She is the kidnap victim of a conformist order which reduces freedom to prodigy status. She is the little girl the beggar pushes onto the sidewalk when back home the mattress is stuffed with money.”[39] Through Minou’s own delectably violent words, we look at her with “greedy eye like children’s eyes / who looking at pastries / undress the icing / from cakes all crackly with frost / mouth which nibbles with no respite / this tragic candy, time.”[40]

Barthes is anorexic when it comes to eating Drouet. “It may happen that I feel no hunger for the world,” claims Barthes in The Neutral, “but the world will force me to love it, to eat it, to enter into intercourse with it.”[41] Barthes tells us that “society is devouring Minou Drouet,”[42] but he remains tight-lipped, refusing to partake in “this tragic candy.”

Completely sugarcoated and consumed by the time she was fourteen, Minou lost her passionate desire to write.

As in the years before she was six, Minou is once again silent. She is back to sleep, forever held as the bowed, Bellmeresque little girl of “tragic candy, time,” with no hope of being de-windowed (“dévitriné”),[43] of escaping her crystal cage, her glass coffin. Forever and ever, she is stuck as a little girl in the glass-covered daguerreotype of her eight-year-old self.

I look at a photograph of Minou at age eight and I “shudder” at the loss of this little girl. As Barthes writes about the Winter Garden Photograph (which captured his mother as a little girl): “I shudder [je frémis] like Winnicott’s psychotic patient, over a catastrophe which has already occurred.” (In English, shudder is a homonym for shutter.)

- Roland Barthes, “Myth Today,” in Mythologies, ed. and trans. Annette Lavers (New York: Hill and Wang, 1972), p. 57.

- Vladmir Nabokov, The Annotated Lolita, ed. Alfred Appel, Jr. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1977), p. 133.

- Simone de Beauvoir, “Brigitte Bardot and the Lolita Syndrome,” in Elizabeth Sussman and Sidra Stich, eds., Rosemarie Trockel (New York: Prestel, 1991), p. 55.

- Beauvoir, “Brigitte Bardot,” p. 54.

- James Kincaid, “Dreaming the Past,” paper presented at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, 24 April 1993.

- Barthes, “Myth Today,” p. 109.

- Roland Barthes, “Preface to the 1970 edition,” Mythologies, p. 9.

- Barthes, “Myth Today,” p. 149.

- The term nymphancy is Nabokov’s as used in Lolita, p. 224.

- Robert Gottlieb, “A Lost Child: The Strange Case of Minou Drouet,” The New Yorker, 6 November 2006, p. 70.

- Jean-Max Tixier, “Notes,” in Minou Drouet, Ma vérité (Paris: Editions 1, 1993), p. 14.

- Sarah Sun-Lien Bynum, Madeleine Is Sleeping (New York: Harcourt, 2004), p. 72.

- Roland Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1978), p. 38.

- Richard Howard, “Childhood Amnesia,” Yale French Studies, no. 43 (1969), p. 165.

- Charles Templeton, An Anecdotal Memoir (Toronto, ON: McClelland and Stewart Limited: The Canadian Publishers, 1983), p. 111.

- Gottlieb, “A Lost Child,” p. 73.

- James Kincaid, Erotic Innocence (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2000), p. 53.

- Minou Drouet to Yves Nat, letter in First Poems, trans. Margaret Crossland (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1956), p. 67.

- Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, “A Poem Is Being Written,” in Tendencies (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993), p. 182.

- Drouet to Nat, First Poems, p. 67.

- Bellmer took the picture in 1935 and then had it hand-colored in 1949. See Sue Taylor, The Anatomy of Anxiety (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002), pp. 78, 204.

- Minou Drouet, “Photographie,”in Le Pêcheur de lune (Paris: Editions Pierre Horay, 1959), p. 79. (“Je ne vous avais apporté / qu’un si laid visage, / un nez pour téléphoner / aux nuages …”). My translation.

- Gottlieb, “A Lost Child,” p. 76.

- Minou Drouet, “Tree that I Love,” in First Poems, p. 3.

- Barthes, “Myth Today,” p. 109.

- “Kitten on the Keys,” Time, 28 January 1957.

- Templeton, An Anecdotal Memoir, p. 112.

- Gottlieb, “A Lost Child,” p. 72.

- Minou Drouet, “Ciel de Paris,” in Le Pêcheur de lune, p. 27. (“Ciel de Paris, / poids, / secret, / chair, / qui, par hoquets, / crache à nos faces / par la gueule ouverte des rangées de maisons / un jet de sang entre ses chicots lumineux...”). My translation.

- The glass slipper is Disney’s addition. In the original fairy tale, the wicked sisters lop off heels and toes in order to squeeze into the slipper. However, given that Disney’s Cinderella was produced in 1950, it does make a snug fit with Drouet.

- Roland Barthes, “Literature According to Minou Drouet,” trans. Richard Howard, in Eiffel Tower and Other Mythologies (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979), p. 111. As stated, the essay was cut from the English edition of Mythologies, but it does reappear here in this collection of translated essays.

- Minou Drouet, “The Watch,” in Then There Was Fire: Further Poems by Minou Drouet (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1957), p. 32.

- Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), p. 91.

- Michael Moon, A Small Boy and Others: Imitation and Initiation in American Culture from Henry James to Andy Warhol (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1998), p. 138.

- Barthes, “Literature According to Minou Drouet,” p. 112.

- Ibid., p. 114.

- Ibid., p. 116.

- Howard, “Childhood Amnesia,” p. 166.

- Barthes, “Literature According to Minou Drouet,” p. 118.

- Drouet, “The Watch,” p. 32.

- Roland Barthes, The Neutral: Lecture Course at the Collège de France (1977–78), trans. Rosalind Krauss and Denis Hollier (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), p. 153.

- Barthes, “Literature According to Minou Drouet,” p. 118.

- Barthes uses this term in another context to describe Bernard Faucon’s photographs of mannequins, who appear to have been awakened as if they had escaped the department store window. See Barthes’s “Bernard Faucon,” in Oeuvres complètes, Tome V, 1977–80, ed. Éric Marty (Paris: Editions du Seuil, 2002), p. 472.

Carol Mavor is professor in the Department of Art History and Visual Studies at the University of Manchester. She is the author of three books, including Becoming: The Photographs of Clementina, Viscountess Hawarden (1999) and Pleasures Taken: Performances of Sexuality and Loss in Victorian Photographs (1995), both published by Duke University Press. Currently, she is completing a series of short essays on the color blue to be published under the title Blue Mythologies (Reaktion Books, 2011).

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.