Who Knows This Man?

The mysterious amnesiac of Collegno

George Prochnik

Early in the spring of 1926, an imposing man with a grizzled, spade-shaped beard was found wandering dazedly through Turin Monumental Cemetery. The police asked him who he was and what he was doing in the graveyard. “Oh the war, the war!” he moaned. “Leave me in peace—my family!” On being further pressed, he announced that he had no identity documents, nor any recollection of his past. When the police opened his coat to verify the absence of papers, they discovered it concealed a hefty bronze mortuary urn. “I’m not a thief!” he cried—but this seemed all he knew about himself. A search of his pockets revealed a postcard from his “affectionate Giuseppino,” nothing more. Eventually, he was carted off to the Collegno Asylum, where he was diagnosed as an amnesiac.[1]

The mysterious inmate number 44.170 behaved with great consideration toward his fellow patients and demonstrated admirable zeal in his Catholicism. He could cite snippets of Nietzsche and Ovid. But the entries in his diary were riddled with immature spelling mistakes. And he sometimes lapsed into terrible melancholy. Most perplexingly, unlike the vast majority of the many amnesia cases that had come to the Collegno since the war, doctors were unable to make any progress whatsoever toward restoring the man’s memory.

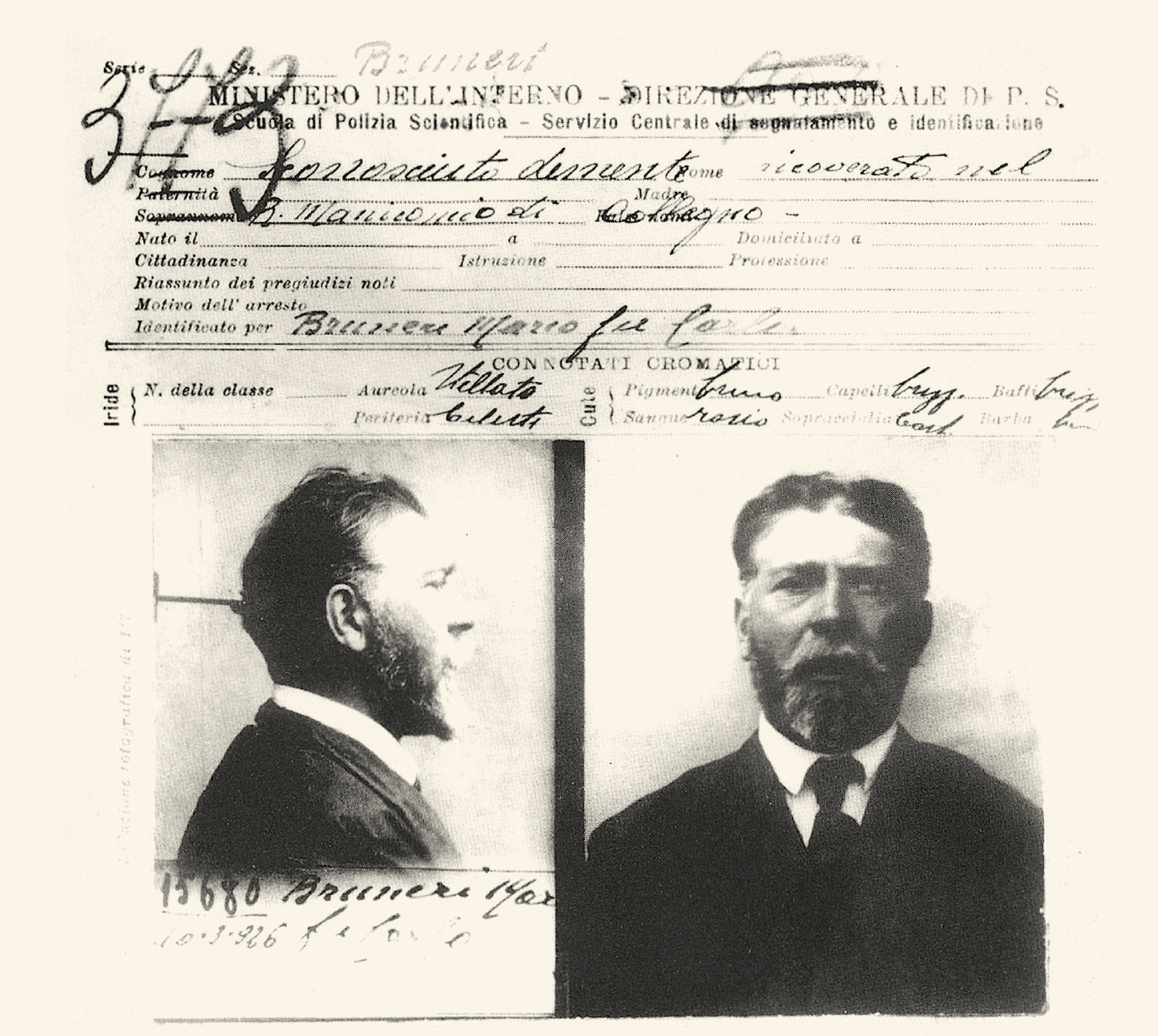

After almost a year without making headway, the frustrated asylum director took the unusual step of publishing the man’s photograph in newspapers above a caption reading, “Who Knows This Man?” As “lo smemorato di Collegno” (the Collegno amnesiac), the unknown man gained national attention. Among those who spotted his photograph was Giulia Canella, an affluent woman of Verona whose distinguished professor husband had disappeared, and was presumed to have been killed, while serving with the Italian army in Macedonia during World War I. She had a son called Giuseppe, fondly referred to as Giuseppino. Signora Canella immediately recognized the smemorato as her lost spouse. She showed the photograph to her sister and other intimates. They confirmed the identification. An exchange of letters with the smemorato further bolstered Giulia’s conviction that Professor Canella yet lived. She traveled to the asylum with a retinue of loved ones to see the man for herself.

From the moment Giulia Canella and the smemorato laid eyes on each other, his memory began to return. He realized that he was, indeed, the missing law professor in whose memory Verona had already erected a monument. The sight of acquaintances from years gone by left him, witnesses reported, “transfigured with sincere emotion.” After several subsequent visits, any lingering doubts in Giulia’s mind about the man’s identity vanished. His beard was cut at the same angle. His shoulders sloped at the same pitch. A scar on the smemorato’s back marked the spot where Professor Canella had undergone an operation for pleurisy. Beyond the physical resemblances, the smemorato correctly answered questions about the professor’s life that could only have been known to the man himself. Overcome with tears of joy, husband and wife embraced each other. Professor Canella was released into Giulia’s care and transported to the family retreat at Dezensano to begin the long course of rehabilitation that would fully return his past to him. The case files were closed. A simple, touching story of wartime loss and marital fidelity had ended with the miraculous restoration of a fallen patriot to life.