Chronophilia

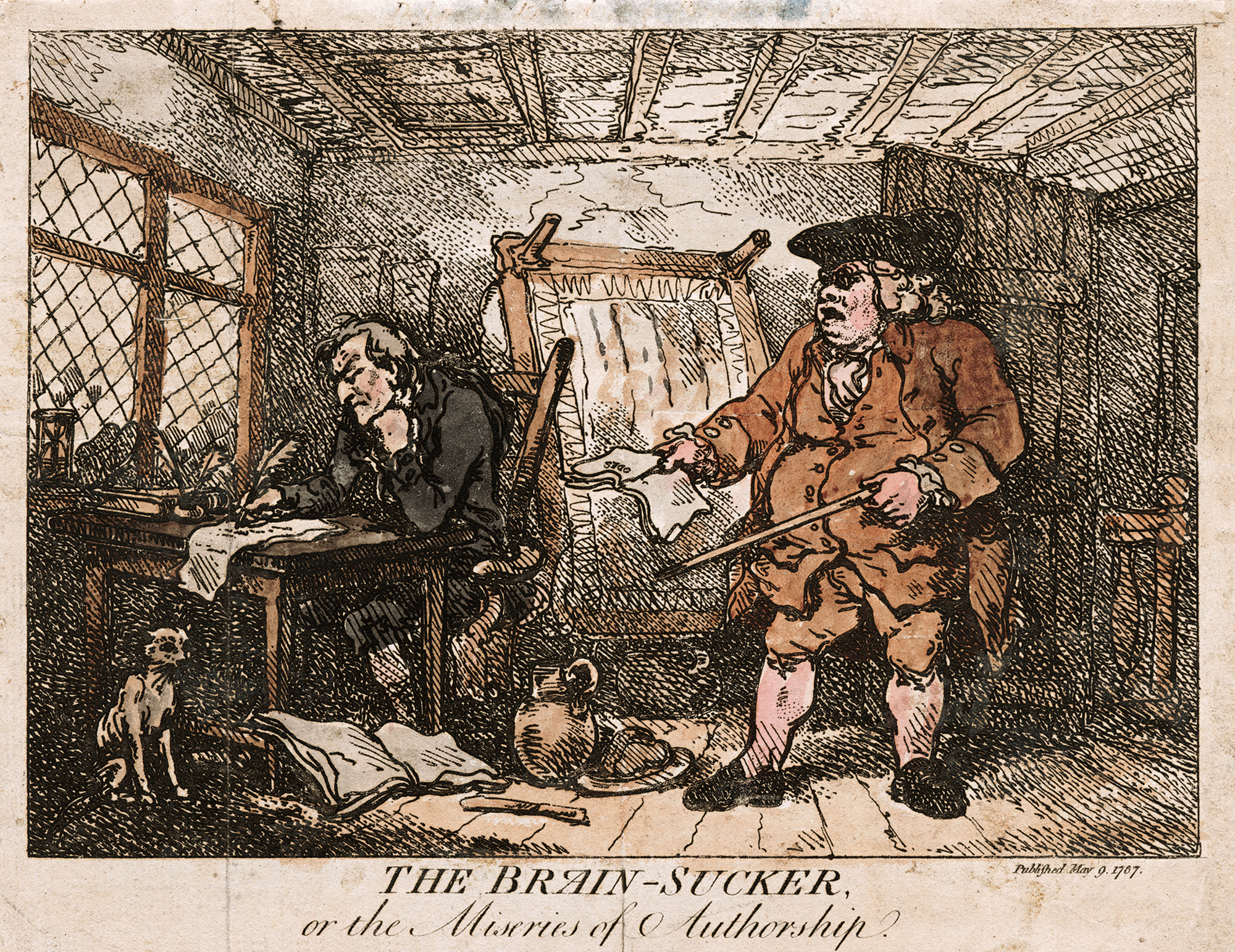

The miseries of authorship

Tirdad Zolghadr

This contribution to Cabinet’s “24 Hours” issue was completed in Barrytown, New York, in 23 hours, 44 minutes.

Many years ago, I attended a Toni Morrison reading. She was suffering from a bad cold, and was dabbing her nose with some type of herbal liniment at regular intervals. This was spectacular to watch. Morrison had prodigiously long, brightly colored fingernails that she would dip in the ointment and tap her nostrils with. All through this undoubtedly tickly, scratchy treatment, dispensed with great punctuality every two minutes perhaps, she would talk at length about arguments with her college students. The students would routinely complain about having to rewrite their seminar papers. And Morrison would explain that if they didn’t like the smell, the touch, the materiality of paper, if they didn’t relish the physical act of administering ink to a page, they were in the wrong field. I liked that. And I looked forward to saying that to my own students one day, as I made them rewrite their papers, again and again.

However, at second glance, though there may well be a faint, libidinal charge to the tap of your fingertips against the keyboard, it’s pretty quaint when compared to what was once the mental erotica of ink on paper. Instead, as I’ve pursued my teaching, I’ve become more interested in whether time itself can offer a similarly specific materiality. Not abstract as a deadline or a Kantian proposition, but palpable as a notebook, or even gummy and viscid, like oils on swollen sinuses. Can you apply the criteria of the haptic to the telos of minutes and hours unfolding? To many, the question may seem hackneyed, a path well-trodden. But to be honest, it’s come to define a lot of what I do, and the seminar room only makes it worse.

My wife, incidentally, says I’ve been speaking more slowly since I started teaching. It’s fascinating to consider that, within any given time frame, whether at the dinner table or in class, I impart much less content than before. Then there’s the question of the very nature of the time at my disposal. Compare an afternoon class to a morning one. Morning classes, in the promising glow of a new dawn, are for positions and positionings, eyebrows raised, heads shaken, eyes rolled, splashy pop references, Slavoj Žižek. Afternoon classes are melancholic, autumnal, historical. Cabinet magazine and T.S. Eliot. You arrive late, you’re self-ironic, you allow for impenetrable pauses and viscous silences. You might say this is all about atmosphere, or bodily rhythms. The morning brings a mystery, the evening makes it history. Big deal. But that’s placing the cart before the horse. Trust me.