Dada on Trial

The Barrès affair and the end of a movement

Colby Chamberlain

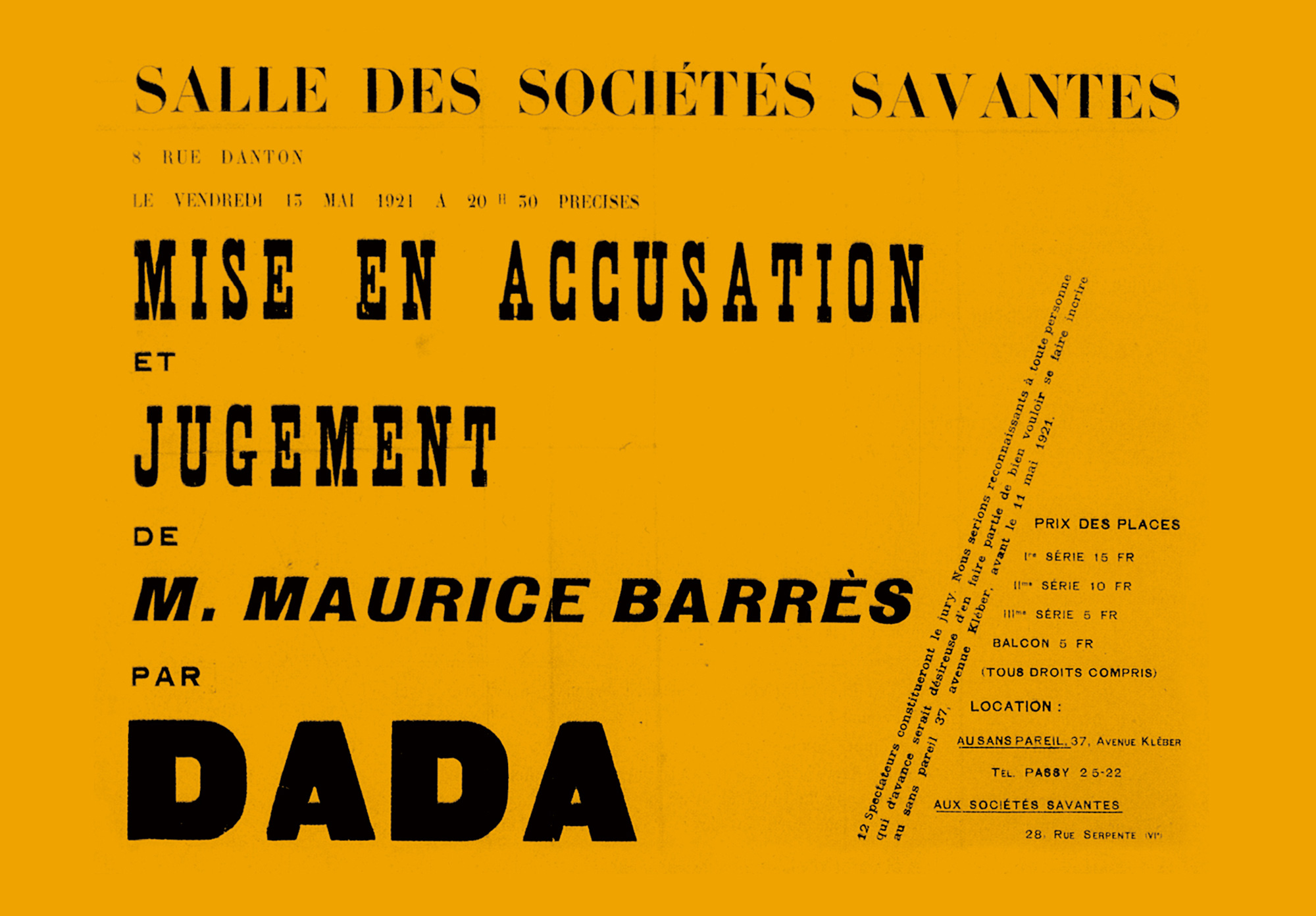

First, the facts: on Friday, 13 May 1921, members of Dada’s Paris contingent put the author Maurice Barrès on trial. The proceedings took place in the Salle des Sociétés Savantes, which had been rented out for the occasion. André Breton acted as chief magistrate; Théodore Fraenkel and Pierre Deval, associate judges; Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, the prosecution; Philippe Soupault and Louis Aragon, the defense. They wore matching outfits: white shirts, aprons, and rounded hats with ornamental tufts on their top (scarlet for the judges and prosecution, black for the defense). Their makeshift courtroom consisted of several music lecterns. Following an acte d’accusation written and read aloud by Breton, several witnesses submitted to questioning: Serge Romoff, Tristan Tzara, Giuseppe Ungaretti, Madame Rachilde (Marguerite Valette), Jacques Rigaut, Pierre Drieu la Rochelle, and Benjamin Péret. Though there is no corroborating evidence, a flyer advertising the trial suggests that several other witnesses, culled from within and beyond Dada’s immediate circle, might also have participated: Marguerite Buffet, Renée Duman, Louis de Gonzague Frick, Henri Hertz, Achille Le Roy, Georges Pioch, Marcel Sauvage, “etc.” Throughout his testimony, Drieu la Rochelle smoked a cigarette; Tzara concluded his remarks with a song; Péret arrived dressed as a soldier and caked in mud. Delivering a lecture in Aix-en-Provence at the time, Maurice Barrès was not in attendance. In his stead sat a mannequin, dressed in a three-piece suit, with a bowtie and a prim, painted mustache. Above the stage hung a banner reading, “NUL N’EST CENSÉ IGNORER DADA” (No one should be ignorant of Dada).

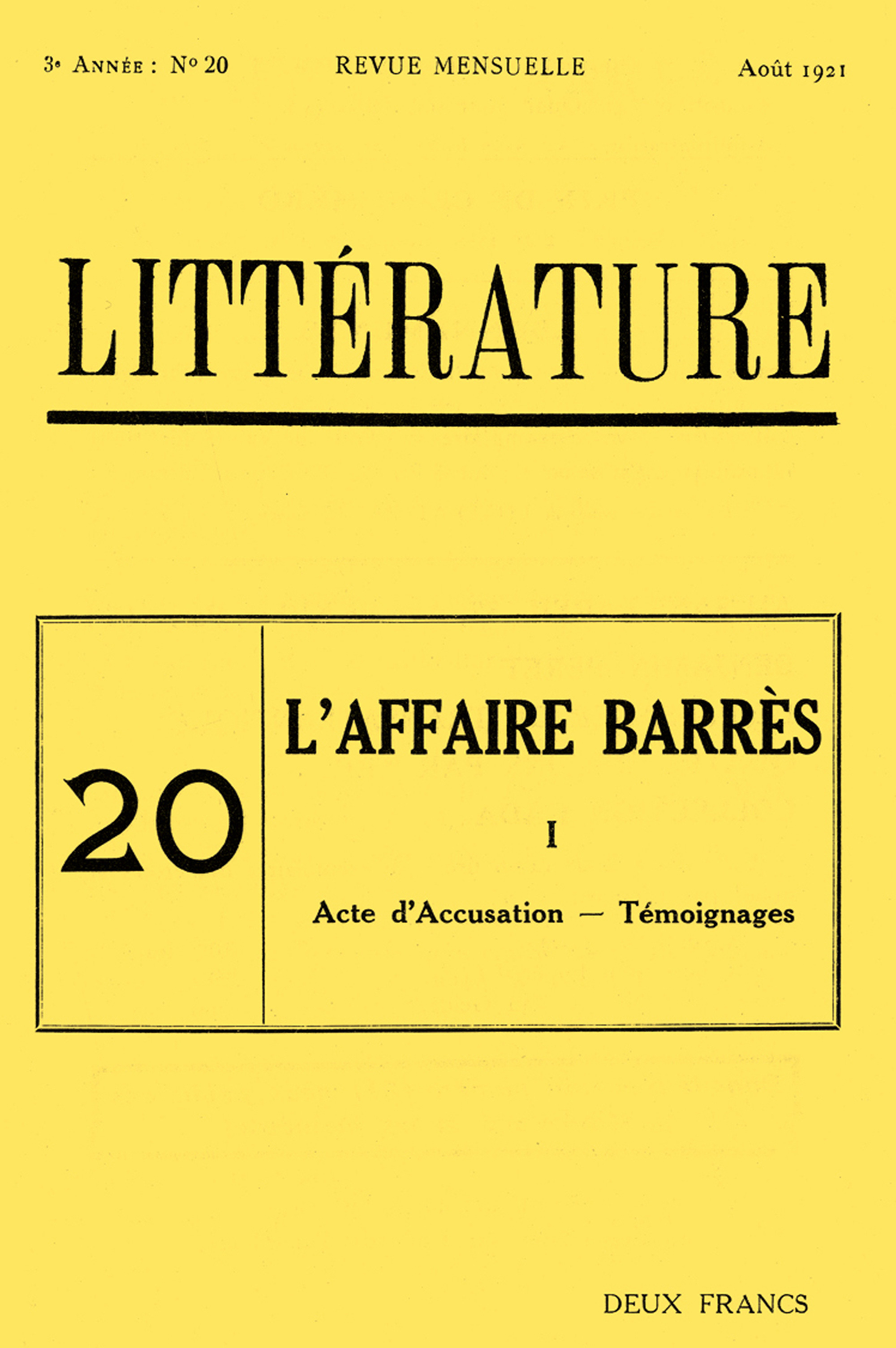

How did this scene come about? Let’s start with a meeting on 19 October 1920 at the restaurant Blanc on rue Favart. Under discussion were new editorial directions for Dada’s publication Littérature. In a strange affront to the journal’s title, the group agreed to stop publishing any text readily identifiable as literature. But what would replace it? This very conversation on rue Favart would became a premier example of Littérature’s latest turn. The meeting was conducted and recorded as a procès-verbal—the French term for the official minutes of a legislative body. The journal’s new editorial policies were determined by a series of majority votes, which were made public in Littérature’s December 1920 edition.

b. Will poetry continue to have a place in LITTÉRATURE?

No, by 6 voices to 2 (Eluard, Fraenkel). ...

g. Could language be a goal?

No, unanimously minus one (Éluard).[1]

The transcript concludes on a note of playful ambivalence: “None of the members support the principle of committees, nor, naturally, that of the vote, but they consider it an experience.”[2]

Such “experiences” characterized the Paris Dadas’ activities for the next several months. Searching for forms that exceeded the “strictly literary,” the Dadas made frequent recourse to bureaucratic procedure. The Procès-Verbal anticipates the Grande Saison Dada, an eclectic series of events officially declared in Littérature’s May 1921 issue:

Ouverture de la GRANDE SAISON DADA — Visites * Salon Dada * Congrès - Commémorations * Opéras * Plébiscites * Réquisitions * Mises en Accusation et Jugements.[3]

Plebiscites, commemorations, trials, congresses, requisitions: the young radicals aspired to the trappings of a revolutionary government. As Aragon put it, “We compared our intellectual climate with that of the French Revolution. It was necessary to prepare and suddenly decree the Terror. … For our part, we decided not to wait for ‘93; the Terror right away, in ‘89.”[4]

And for a revolutionary government, a revolutionary tribunal. Ergo: the Barrès trial. However, it is evident that Breton and Aragon led their associates into this novel format without full consideration of its possible ramifications. The aims and outcomes of the Barrès trial compromised the already fragile unity of Dada’s Paris membership. It was Tristan Tzara—the Romanian provocateur originally responsible for exporting Dada from Zurich to Paris—who had insisted on including “operas” in the Grande Saison’s program to add a dose of levity, and it was Tzara who in his testimony strongly rejected the trial’s very premise: “I have no confidence in justice, even if this justice is made by Dada. You’ll agree with me, Mr. Magistrate, that we are all just a pack of bastards, and consequently little differences, like big bastard or small bastard, are not important?” Tzara’s screed was perhaps the most blatant instance of the strange phenomenon that unfolded through the proceedings: though the accusation was weighed against Maurice Barrès, it was Dada on trial.

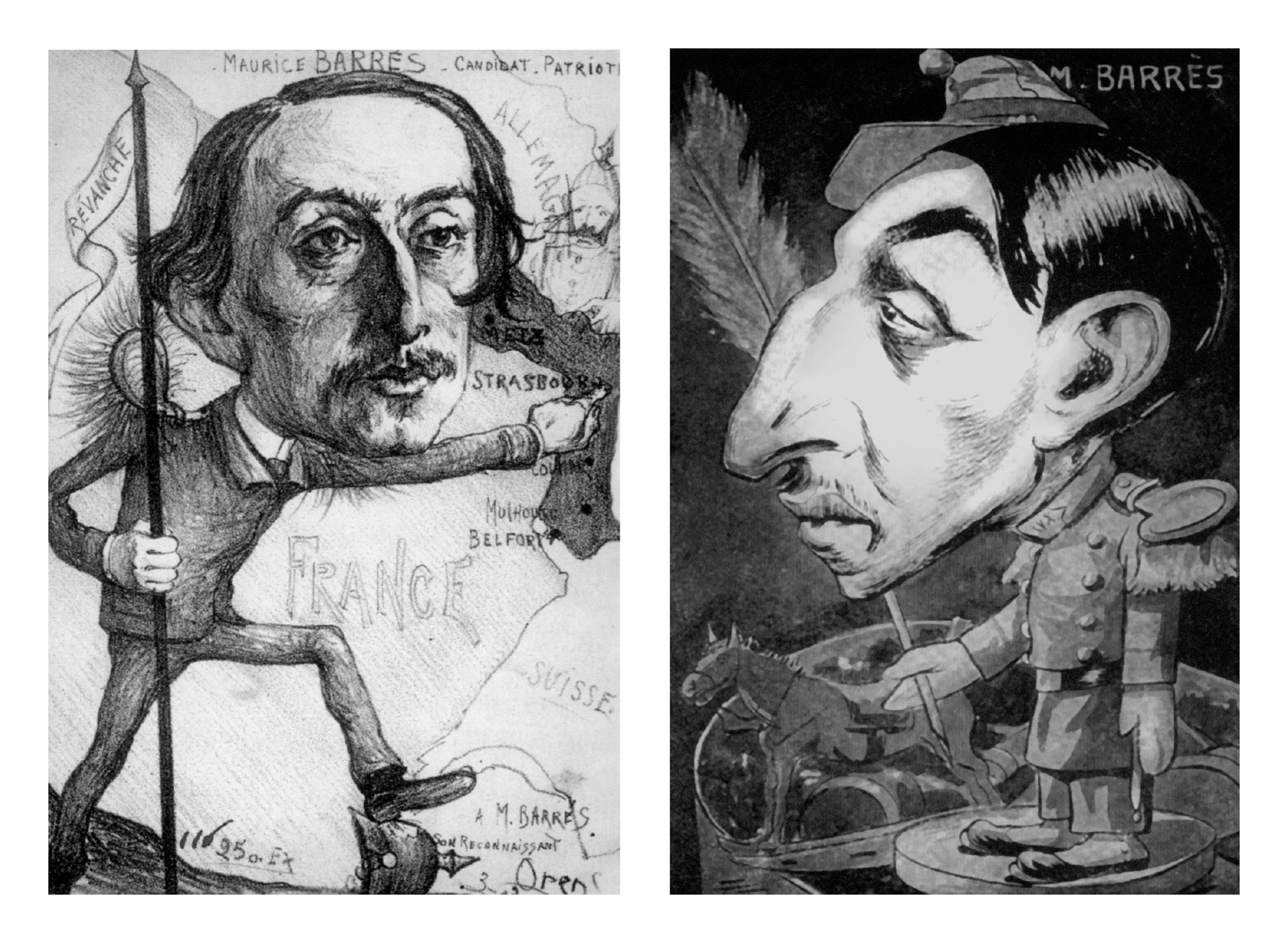

Author of three volumes gathered under the title The Cult of the Self, of The Enemy of Laws, of Eight Days at the Home of M. Renan, decadent writer, propagandist of the school of the novel, author of Les Déracinés, of Colette Baudoche, and of Chronicle of the Great War, former socialist, delegate, atheist, one of the mainstays of boulangisme, one of the lieutenants of Paul Déroulède, one of the agitators in the Dreyfus affair, one of the whistleblowers of Panama, nationalist, apostle of the Cult of the Dead, president of the League of Patriots, academic, editor of L’Écho de Paris, popular lecturer, author of The Great Pity of the Churches of France, partisan of la revanche, the man of the statue of Strasbourg, the man of the annexation of the left bank of the Rhine, the man of Jeanne d’Arc, honorary president of a hundred seventy-five charitable organizations.[5]

This litany provides both a résumé for Barrès and a reasonably thorough catalogue of turn-of-the-century France’s tumultuous politics. To restate, Maurice Barrès was a writer who came to prominence in the 1880s, while still in his twenties. His earliest volumes advocated a “cult of the self,” an anarcho-individualism that valorized personal cultivation over existing social structures. This rebellious philosophy was foremost a matter of aestheticism, and quite thin on political conviction; nevertheless, Barrès became deeply involved in politics. Though he had few fixed views on government and policy, Barrès was instinctively drawn to strength, and he became swept up in the movement coalescing around General Georges Boulanger. A career military officer of limited accomplishment but great charisma, Boulanger was briefly the impetus for several unlikely political alliances; royalists and socialists alike came to see Boulanger as the vehicle for their agendas. In 1889, Barrès returned to his native Lorraine under the boulangiste banner and served, rather ineffectually, as a representative in the Chamber of Deputies. When the boulangiste movement collapsed, Barrès was forced to choose among its diverse strains and gravitated towards the extreme nationalism of Paul Déroulède, founder of the League of Patriots. The youthful Barres’s advocacy for personal strength gave way to the arguments of Les Déracinés (1897), which located the source for that strength not in the self but in soil, blood, and tradition. Ubiquitous in France’s press and politics, the aesthete who had once rejected society’s fetters became a staunch defender of the country’s entrenched institutions—the army, the church, the saber-rattlers who called for la revanche against Germany.[6]

Yet despite this about-face, Barrès remained a preoccupation among Paris’s young intellectuals, even after he succeeded Déroulède as the League of Patriots’ president during World War I. The French contingent of Dada’s membership actively courted his favor. In a July 1919 letter to Tzara, Breton mentioned that they were pursuing Barrès to preface the collected letters of Jacques Vaché, a friend of Breton’s who had died that year of an opium overdose. The following year Breton sent Barrès a copy of The Magnetic Fields, and Soupault presented him a copy of his poetry collection Rose des vents. In short, Barrès was an object of ambivalence, worthy of vehemence but commanding admiration. “If the virtue of Barrès were certain in our estimation, and sincere, we wouldn’t have ever bothered to judge him,” explained Ribemont-Dessaignes in his closing remarks for the prosecution. “A simple execution would have sufficed.”[7]

Rachilde captured the mood of the room well when she scolded the Dadas for their sudden dullness:

Throw peas and haricot beans [in the public’s face] once, and they will be indignant if you later content yourself with presenting them with a more or less intelligent conference about an individual or a work. Then they will throw peas and haricot beans at the new face you show them. … You must not base a system of critique … on a philosophy that seems tedious because it no longer involves animalistic cries or even leguminous projectiles.[9]

Rachilde’s vocal criticism of Dada came as no surprise, since as the editor of the literary magazine Mercure de France she had previously expressed her distaste with the group; the one Dada with whom she was on good terms was Francis Picabia, who himself so disliked the trial—which he attended but did not participate in—that he had announced his resignation from Dada the week prior in Comoedia. Nevertheless, she was sufficiently bemused with the notion of prosecuting Barrès to participate. Her inclusion points to Breton’s ambition that the trial comprise a cross-section of Paris’s intellectual scene that extended past Dada’s closed ranks. Historian Michel Sanouillet, however, detects in the diverse selection an ulterior motive: that by amassing a roster of participants who would execute their role conscientiously, Breton was hoping to offset Tzara’s inevitable antics.

For Breton, the solemn air reflected the trial’s seriousness of purpose. In an essay written later that month, he confessed to a yearning for rigor: “It is absurd that poetic or philosophical ideas should not be amenable to immediate application like scientific ideas. Surrealism, psychoanalysis, the principle of relativity must lead us to build instruments as precise and as well adapted to our practical needs as the wireless [telegraph].”[10] For Breton, the Barrès trial was an attempt to build such an instrument, one capable of judging accurately Barrès’s contradictions through the application of legal process. “The problem [of the Barrès trial],” Breton later explained in a 1952 radio interview, “is knowing by what measure to hold guilty a man that the will to power has compelled to champion conformist ideas completely at odds with those of his youth.”[11]

Breton, then, sought to turn Dada into a calculator for moral judgments. Tzara, on the other hand, held to the inspired irrationalism of the movement’s origins. This much was evident from his testimony, which was emphatically out of step with the rest of the proceedings. He fabricated a tale of falling out with Barrès in 1912 (when Tzara would have been sixteen); he called his fellow Dadas pigs; he warbled a nonsense song about elevators. When Tzara completed his testimony and unleashed his doggerel rhyme, it seemed an attempt to reassert his definition of Dada, one of outburst and absurdity. As it turned out, however, Tzara’s misbehavior was milquetoast when compared to a subsequent disturbance.

For his testimony, Benjamin Péret chose to address the issue of Barrès’s nationalism—in the most incendiary manner imaginable. Dressed in a gasmask and uniform caked with mud, he entered the Salle des Sociétés Savantes and announced himself as the exhumed Unknown Soldier—the single unidentified casualty buried at the Arc de Triomphe as an emblem of France’s sacrifices during the Great War. Ceremonially installed just seven months prior, the Unknown Solider was a powerful symbol of the French patrie, and here was Péret, provocatively assuming the title for himself and parading through the hall in the military colors of Germany.

It was instant scandal. Péret’s appearance as the Unknown Soldier is marked in the trial’s transcript only by three lines of German. “Sie verstehen nicht?” asks a speaker listed as “L’accusateur.” A second speaker, marked simply by an “R” for réponse, answers, “Nein. Ich bin kaput.” “Raus!” the accusateur exclaims, and with that the fragment of German cuts out.[12] The abrupt nature of this entry is a fitting counterpart to what transpired in the courtroom. Patriotic fervor prompted a chorus of “La Marseillaise.” A contingent attempted to bring down the stage curtain. The crowd was in uproar, and no amount of bell ringing on Breton’s part could quell it. Nevertheless, the chief magistrate pushed the proceedings through. When Aragon rose to deliver his speech for the defense, Picabia took the opportunity to make a conspicuous departure. Half the audience followed his lead. The account in Carnet de la semaine described Aragon’s reaction: “Furious, Aragon continued through the din to open his mouth, like a fish in water.”[13]

Indignation over Péret’s performance eclipsed all other aspects of the trial. “After Friday, May 13,” wrote Breton, “we are once again condemned to execration.”[14] Péret’s performance was intended as an attack on France’s extreme nationalism; ironically, the reaction he garnered revealed just how pervasive that nationalism had become. “A few aesthetes who are not from our country, who do not possess the spirit of country, declare that la Patrie doesn’t exist, that the courage of the deserter is worth as much as that of the combatant, that honor is only a word,” fumed the editors of Aux Écoutes. “There’s room to hope that the Dadas will come to understand that there are limits to the grotesque, and that one mustn’t play with certain sentiments.”[15] The paper’s insistence on “sentiments” that were inviolable and sacrosanct underscore the strict boundaries within which a critique of French nationalism could safely occur; moreover, the decision to characterize Dada as outsiders “not from our country” reveals what Dada risked triggering by crossing those boundaries. Given the cosmopolitan makeup of its membership, Dada was not just vehemently opposed to nationalism, but vulnerable to it. “It is seriously time that someone inspect these gentlemen’s papers, which have permitted them up until now to take advantage of the new regulation for foreigners,” La Justice announced, employing elsewhere in the article a derisive slur against foreigners, métèques. “As for the French Dadas, if any exist, a little hydrotherapy could put some reason into them.”[16] With its suggestion of pressure applied directly to the body, La Justice’s invocation of hydrotherapy confirmed the tinge of violence that accompanied its xenophobic reaction to Dada’s actions.

Writing for Comoedia, Asté d’Esparbès recommended a method of punishment that was less physically threatening, but probably more immediately devastating. “They need to be punished: absolute silence regarding their acts and deeds is the heaviest penalty we can apply from now on.” Rather than agitating for attack upon their bodies, Esparbès called to squelch Dada’s publicity. “The Dadas have committed the ‘crime against the integrity of the mind’ that they imputed to the author of Jardin de Bérénice.”[17] It was a cruel reversal: Esparbès had borrowed the key phrase in Breton’s accusation against Barrès—“attacking the integrity of the mind”—and threw it back in Dada’s face. The prosecutors had become the condemned.

Ultimately, however, the disintegration of Dada in Paris resulted more from internal divisions than public opprobrium. The testimonies—particularly the tense tête-à-tête between Breton and Tzara—revealed fissures that resisted repair. Ironically, the Barrès trial’s principal themes of nationalism and legal procedure figured prominently in Dada’s subsequent disputes. In early 1922, Breton attempted to rally the group around organizing a Congrès international pour la détermination des directives et la défense de l’esprit moderne (International Congress to Determine the Aims and the Defense of the Modern Mind), conceived as sort of League of Nations for avant-garde movements. When Tzara declined to participate, Breton denounced him in print as “a publicity-mongering imposter … known as the promoter of a ‘movement’ that comes from Zurich.”[18] The phrase smacked of xenophobia, and support for the congress evaporated quickly thereafter—though not before Tzara and Breton exchanged further volleys across the pages of literary Paris. Then, in July 1923, at a theatrical event organized by Tzara—the infamous Soirée du coeur à barbe—Breton stormed the stage and, with the swift rap of a cane, broke the arm of the poet Pierre de Massot. After Breton was hauled off by the police, his friend Paul Éluard sparked an even larger fracas. When the brawl forced the cancellation of the Soirée’s second performance, Tzara matched Breton in audacity by hiring a lawyer to sue Éluard for the financial losses. Needless to say, this appeal to the law effectively disbanded Dada’s membership. If the Barrès trial is proof of anything, it’s that few friendships survive the courtroom.

Read André Breton and Tristan Tzara’s “L’affaire barrès” in this issue.

- “Procès-Verbal,” Littérature, no. 17 (December 1920), p. 3. All translations mine unless otherwise noted.

- Ibid., p. 4.

- “Ouverture de la Grande Saison Dada,” Littérature, no. 19 (May 1921), p. 1.

- Louis Aragon, “La grande saison Dada 1921” [1923], republished in Marc Dachy, ed., Archives Dada: Chronique (Paris: Hazan, 2005), p. 284.

- André Breton, “Acte d’Accusation,” Littérature, no. 20 (August 1921), p. 2.

- See C. Stewart Doty, From Cultural Rebellion to Counterrevolution: The Politics of Maurice Barrès (Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 1976); Sarah Vajda, Maurice Barrès (Paris: Flammarion, 2000).

- Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes, “Réquisitoire” (1921), republished in Marguerite Bonnet, ed., L’Affaire Barrès (Paris: Librairie José Corti, 1987), p. 64.

- Asté d’Esparbès, “Les dadas ont dépassé la mesure,” Comoedia, 15 May 1921, p. 1.

- “Les Témoins,” Littérature, no. 20 (August 1921), p. 18.

- André Breton, “The Artificial Hells,” trans. Matthew S. Witkovsky, October, no. 105 (Summer 2003), p. 139. For more about Breton’s search for “instruments” of judgment, see Colby Chamberlain, “Keep It Déclassé,” Cabinet, no. 37 (Spring 2010), pp. 7–11.

- André Breton, Entretiens 1913–1952 (Paris: Gallimard, 1969), p. 73. Emphasis added.

- “Les Témoins” (1921), republished with additional material in Marguerite Bonnet, op. cit., p. 61.

- “Encore les dadas,” Carnet de la semaine, no. 311 (22 May 1921).

- André Breton, “The Artificial Hells,” op. cit., p. 142.

- “La profanation,” Aux Écoutes, no. 157 (22 May 1921).

- Montjoye, “Cretinisme Dangereux,” La Justice (15 May 1921).

- Asté d’Esparbès, op. cit.

- Quoted in Mark Polizzotti, “Introduction,” in André Breton, The Lost Steps, trans. Mark Polizzotti (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1996), p. xvi. Emphasis added.

Colby Chamberlain is a Jacob K. Javits Fellow in the art history department at Columbia University and a senior editor of the online magazine Triple Canopy canopycanopycanopy.com.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.