In the Palm of Your Hand

A brief history of dexterity games

Barbara Levine and Jessica Helfand

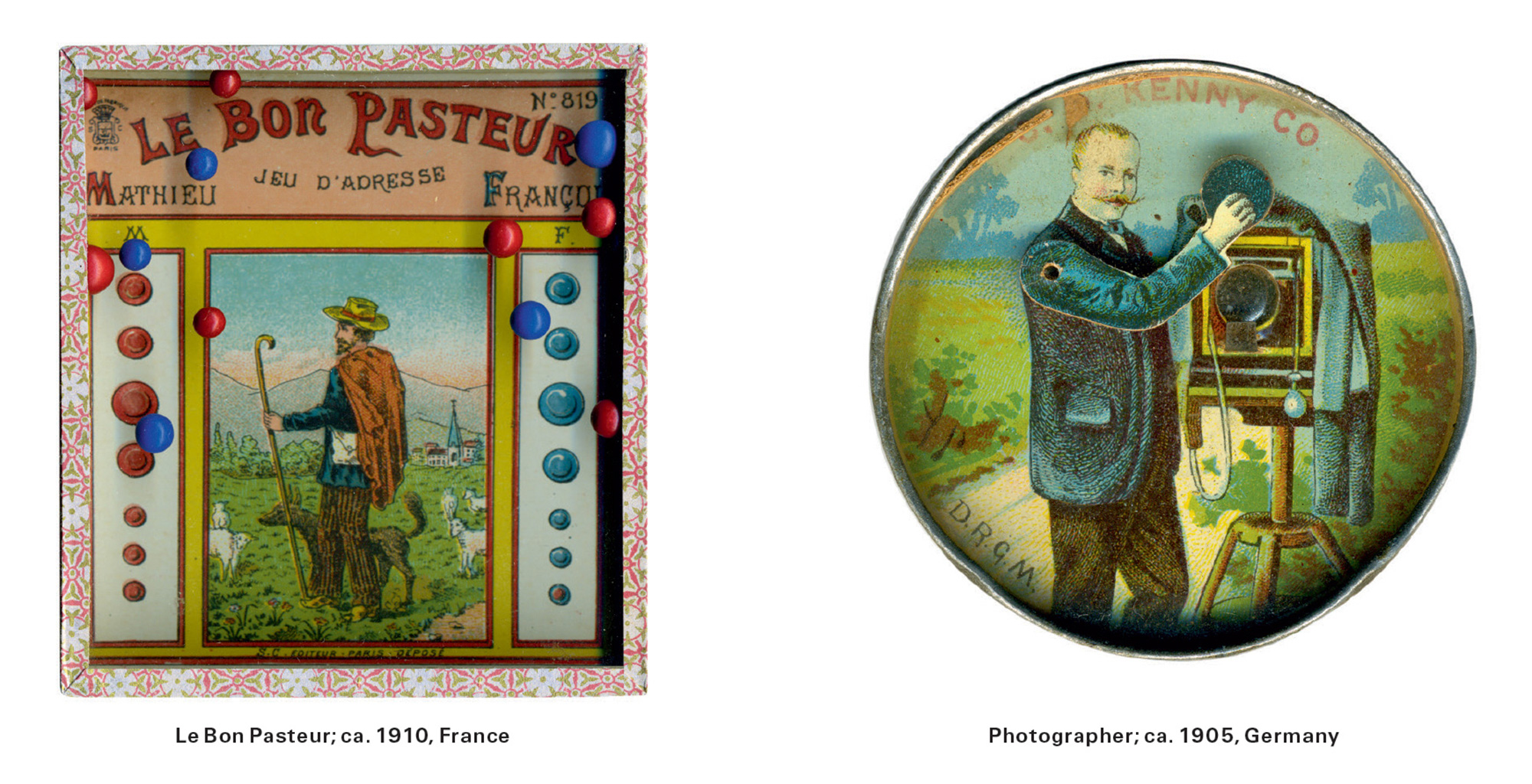

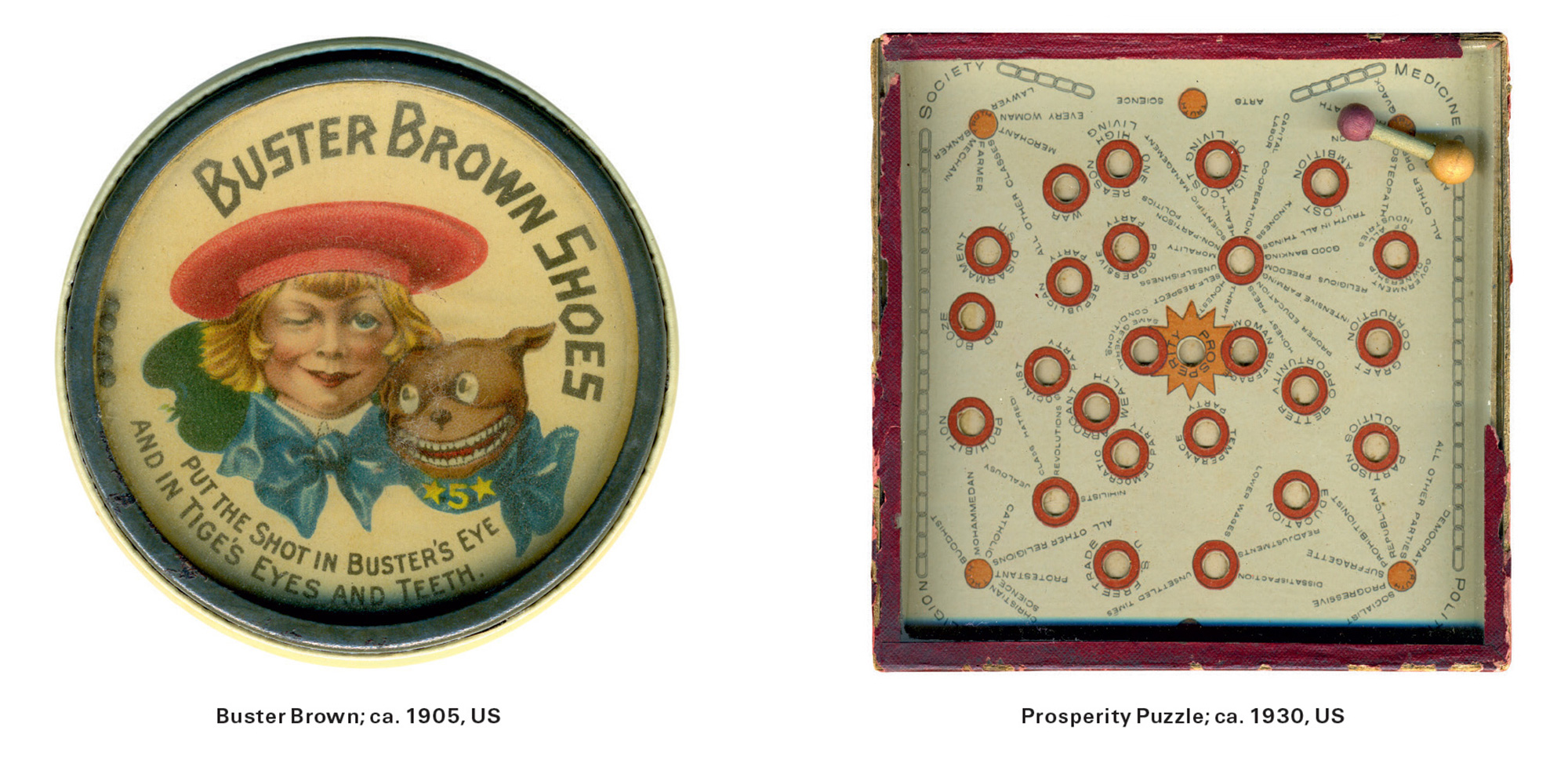

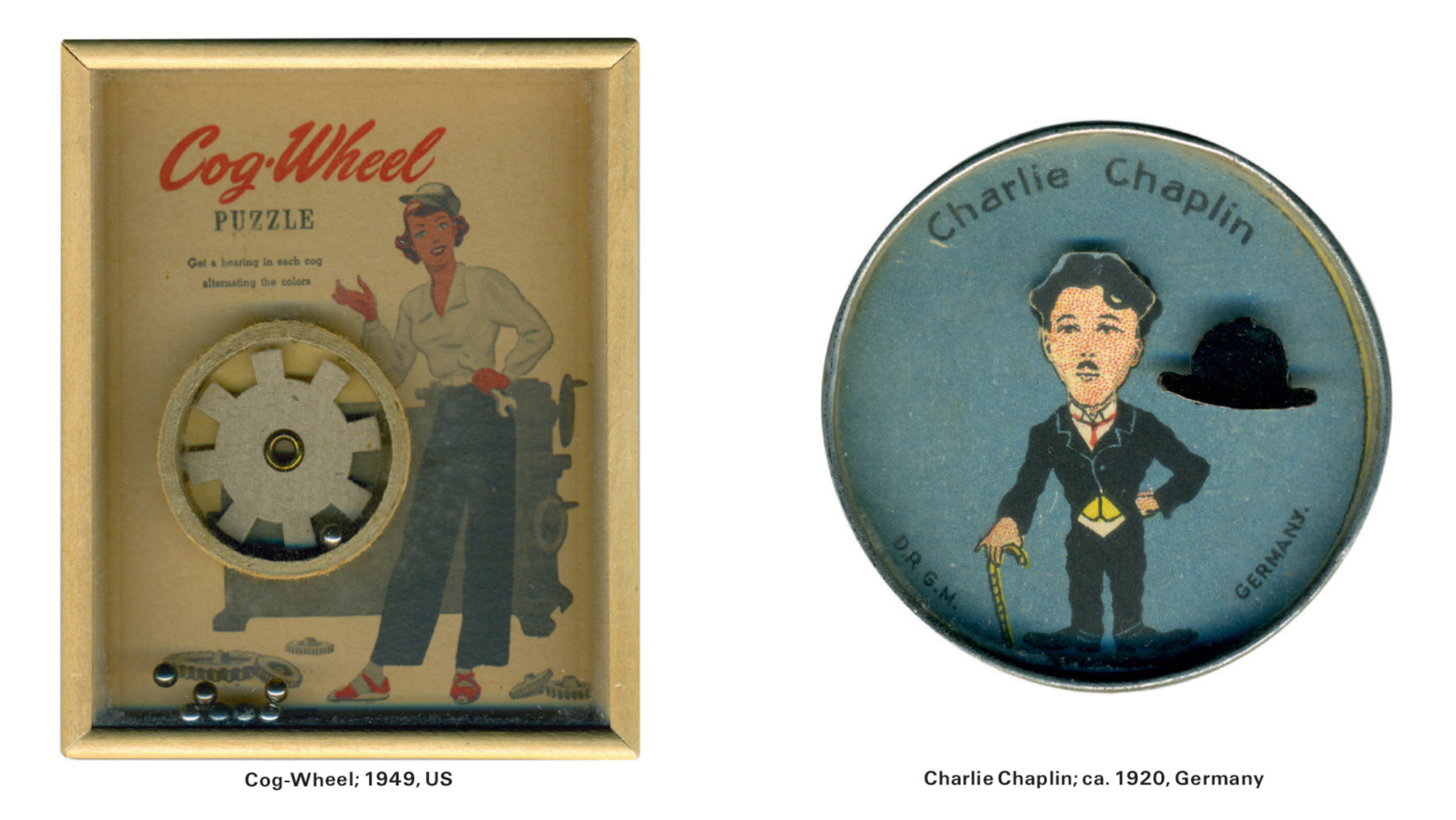

Dexterity games—also known as palm puzzles, games of skill, patience games, and hand-held games—have been a source of fascination for adults and children since the nineteenth century. The fundamental hand-eye challenge of rolling a ball into a hole or tilting a capsule through a maze has proved among the most delightful, maddening, and enduring diversions of the modern age, despite (or perhaps because of) its sheer simplicity.

As vehicles for social history, dexterity games provided an entertaining and perpetually changing canvas of popular culture, one that led to the possibility of an unusual kind of sustained play: because they were so portable, players could easily transport themselves into worlds either familiar or imagined—at virtually any time.

While the first rolling-ball puzzles were available in England as early as the 1840s, it was Charles M. Crandall’s Pigs in Clover, introduced in 1889, that captured the enthusiasm of the American public. Legislators took the game into the senate chambers during debates, and Benjamin Harrison (US president from 1889 to 1893) is said to have played the game in the White House instead of tending to politics. By 1890, Selchow & Righter, manufacturers of the game, claimed that more than eight thousand orders for Pigs in Clover were arriving each day.

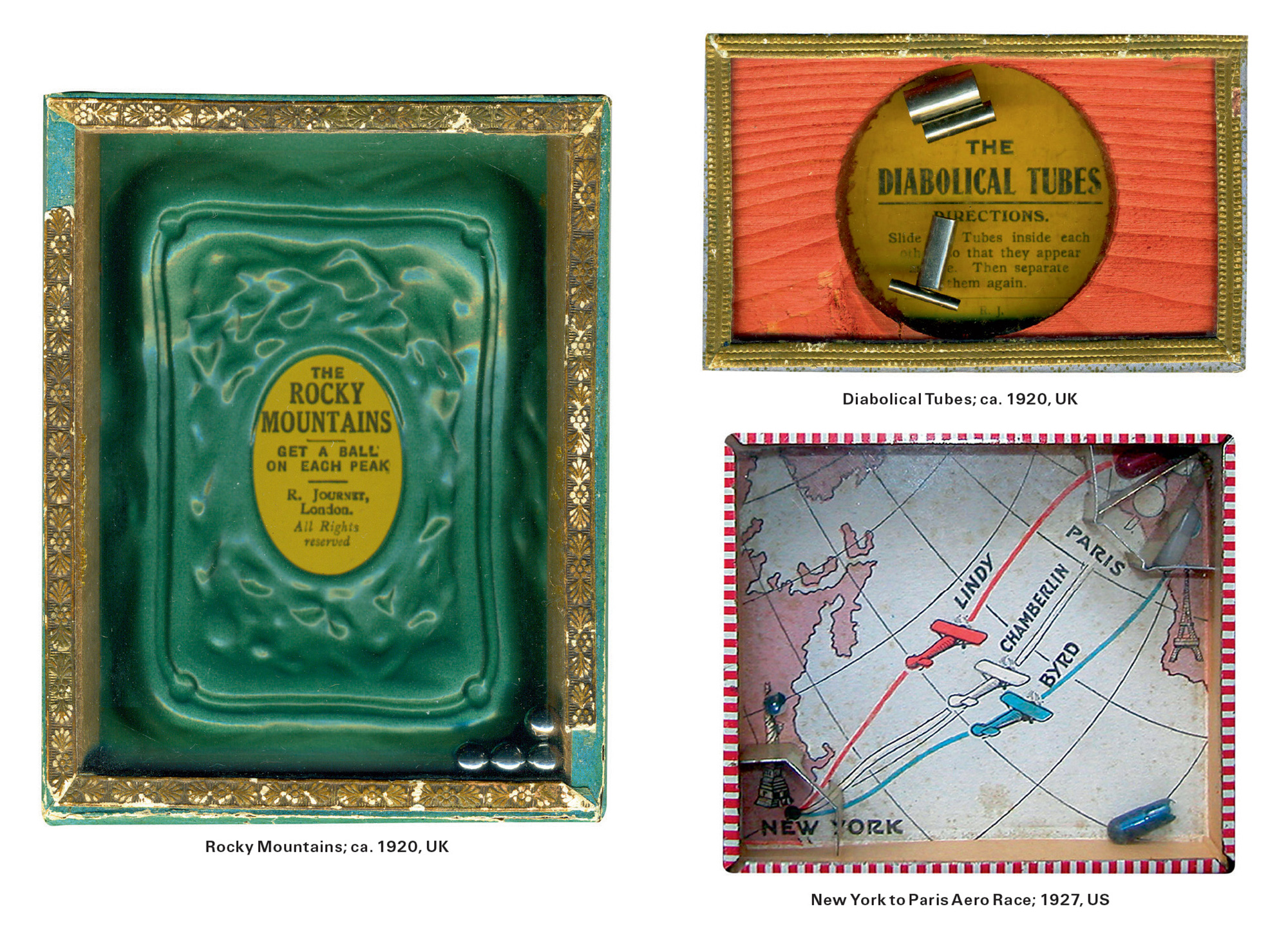

Beginning in 1891, the London-based firm of R. Journet & Company designed more than one hundred innovative glass-top dexterity games. The palm-sized games had wood or metal frames and contained movable objects, including clay or wooden balls, globs of mercury, and capsules loaded with ball-bearings. The first British Industries Fair in 1918 produced orders for large numbers of these “patience games” (especially from the US) and marked the real start of Journet’s puzzle business, which would continue well into the twentieth century. Over the course of these early years, dexterity games gained an international following and were also being produced in significant numbers and with distinctive designs in France, Germany, and Japan.

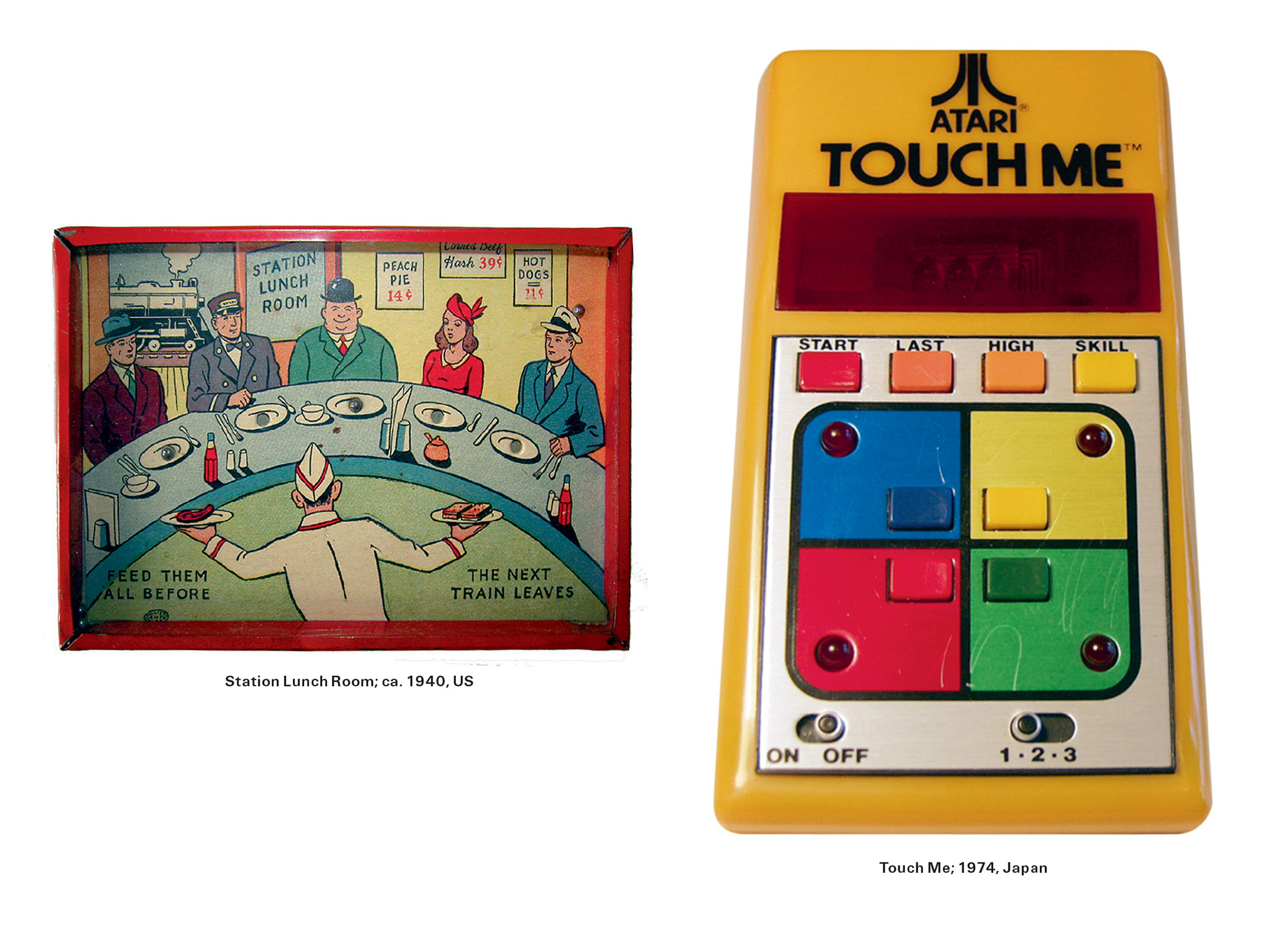

Dexterity games were immediately popular with people of all ages and backgrounds. In addition to the universal appeal of challenging hand-eye coordination, the games were both practical and entertaining. Over the years, the hand-held games became mirrors of a much wider range of consumer culture. Depicting scenes from important centennial events such as the Chicago World’s Fair and the coronation of England’s King Edward VII, they also reflected such simple diversions as baseball, bingo, and Chinese checkers. There were dexterity games featuring popular figures from Popeye, the Lone Ranger, Mickey Mouse, and Superman to Charlie Chaplin, Charles Lindbergh, and the Dionne Quintuplets. There were sports themes featuring fishing or golf; train station challenges showing diner menu items at single-digit prices; and, by mid-century, a number of dexterity games celebrating the wonders of interplanetary space exploration, complete with Martians, spaceships, and asteroids.

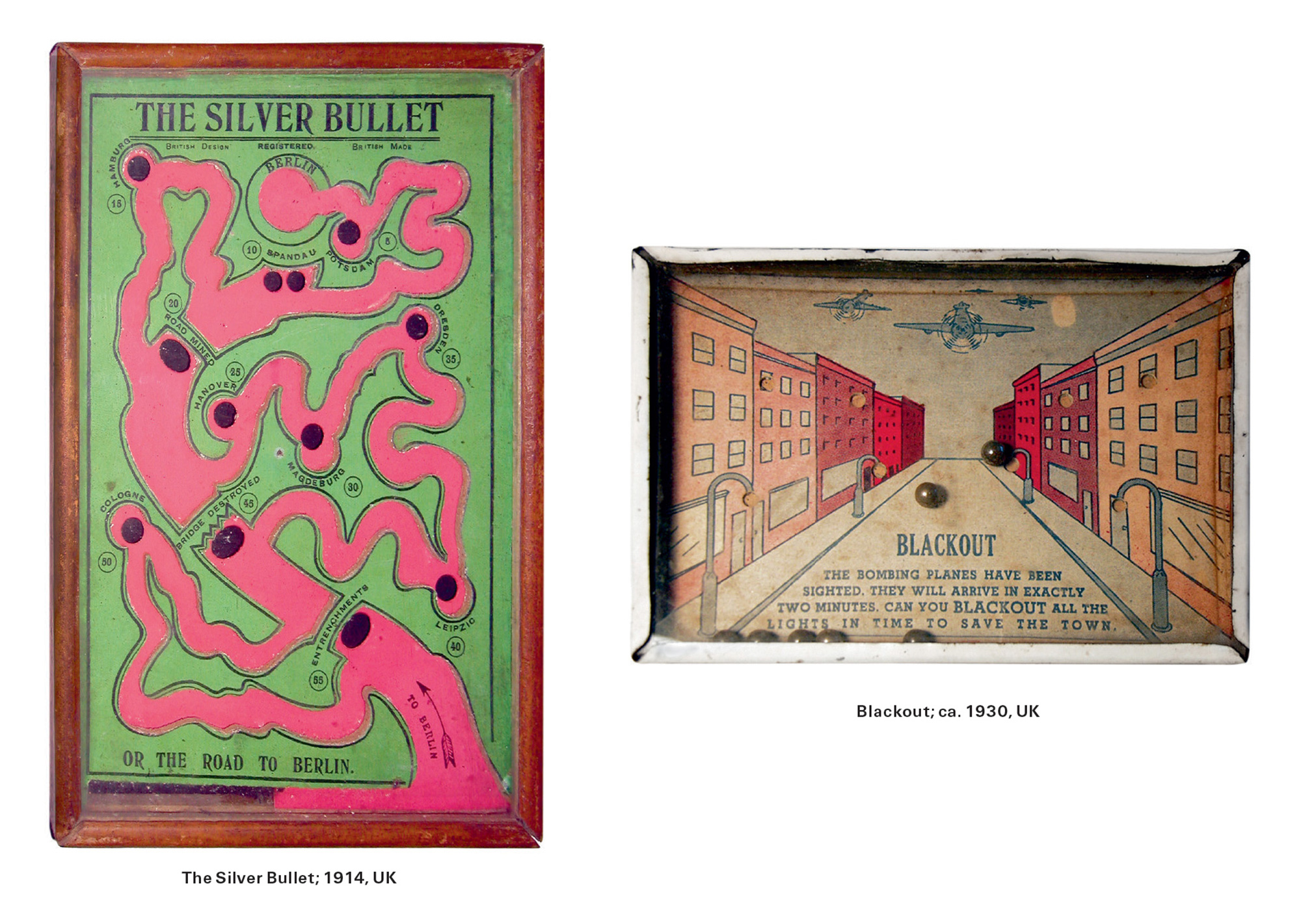

Wartime scenes and military challenges proved especially adaptable to the interests of the manufacturers. The World War I–era game The Silver Bullet, for instance, invites the player to negotiate pitfalls and maneuver the ball safely past German strongholds. Other dexterity puzzle games feature zeppelins to be moored and kaisers to be “kaught,” flight formation line-ups and build-a-plane challenges. One, Rafie’s Rollicking Trip to Berlin, consists of a maze with a small drawing of a saluting Hitler located at the finish line. During World War II, the Gilbert Company of New Haven made Atomic Bomb, a puzzle that let players reenact the bombing of Japan. (By the 1950s, they modified this game to represent a more generic target.)

By the 1960s, dexterity games shifted from vibrant depictions of daily life to an emphasis on mazes, optical illusions, and geometric challenges. Dexterity games and puzzles became known as “brain-teasers,” reflecting a change in emphasis and style that would be hastened by the advent of hand-held electronic games, with their futuristic promise of miniaturized computing. In the mid- to late 1970s, the first wave of these electronic game devices appeared, such as Atari’s Touch Me, Milton Bradley’s Simon, and Parker Brothers’ Merlin. In 1989, Nintendo introduced Game Boy and a flurry of hand-held games followed, most of them oriented toward children.

In recent years, as interactive communication has come to be a ubiquitous part of modern life, our dependence upon point-and-click technologies suggests an interesting connection to games of patience and dexterity. From sending text messages on cell phones to playing games on iPhones and PDAs, hand-eye coordination has never been more central to the way we engage the world. All trace their roots to the charming and engaging dime-store palm puzzles that first capitalized on the basic pleasures afforded by simple hand-eye challenges.

Barbara Levine is a collector, artist, and dealer specializing in vernacular photography and unusual collections. She curated “In the Palm of Your Hand: Dexterity Games, 1880–1960” at the San Francisco Main Public Library in 2002, and is the author of three books, including Finding Frida Kahlo (Princeton Architectural Press, 2009) and Snapshot Chronicles: Inventing the American Photo Album (Princeton Architectural Press, 2006). Levine’s collection of early photograph albums was recently acquired by the International Center of Photography. For more information, see projectb.com.

Jessica Helfand, an award-winning graphic designer, is a partner with William Drenttel in Winterhouse and a founding editor of Design Observer. Helfand is a senior critic at Yale University School of Art and the author of numerous publications on design and cultural criticism, including Scrapbooks: An American History (Yale University Press, 2008) and Reinventing The Wheel (Princeton Architectural Press, 2006). She has been collecting vintage games and dexterity puzzles for more than twenty-five years.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.