Inventory / The Tokens

Orphaned at the Foundling Hospital

Christopher Turner

“Inventory” is a column that examines or presents a list, catalogue, or register.

When the London Foundling Hospital, established “for the maintenance and education of exposed and deserted young children,” opened on 25 March 1741, a crowd of women with their unwanted babies queued outside. At 8 o’clock in the evening, to preserve the anonymity of these guests, the porter put out the lights over the entrance and let the ladies in one by one. The first thirty women whose offspring were deemed healthy enough were relieved of their swaddled bundles.

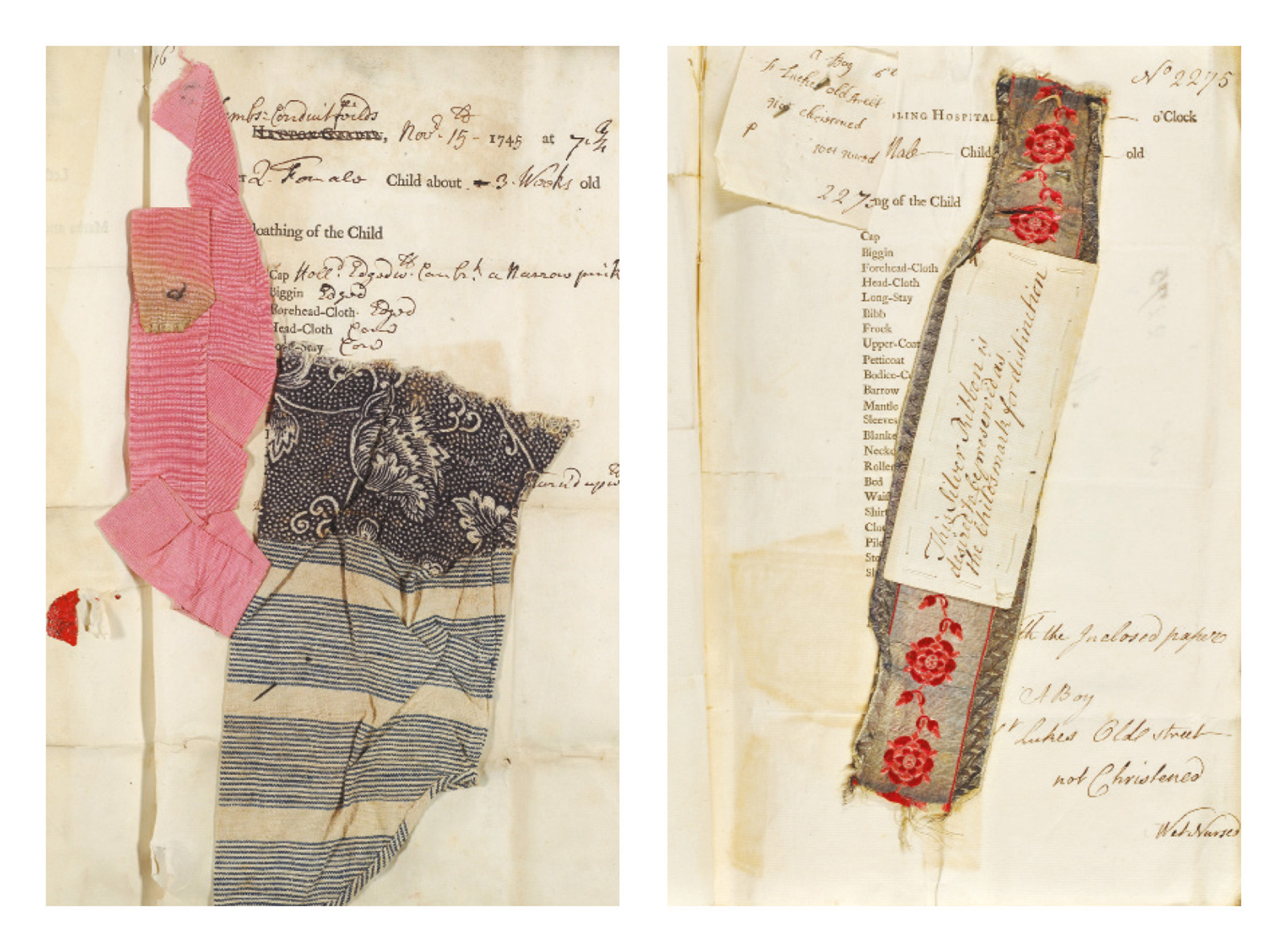

Each baby was numbered and a registration form, or “billet,” listing its sex, age, and what it was wearing was completed; their admittance number was then stamped on a lead tag and placed around their necks. The orphans (all aged two months or less) were baptized and renamed, and were then sent to wet-nurses outside the city with whom they stayed until they were five. Infant mortality rates were high in eighteenth-century London: of this initial intake of infants, many of whom “appeared as if Stupefied with Opiate, and some of them almost starved,” several died within days, and twenty-three within the first few months. Wet-nurses were given a generous annual bonus for keeping their charges alive.

The following year, to prevent “disorderly scenes” and to ensure fairness, a lottery system was introduced. In the hospital’s grand Court Room, watched by the wealthy society ladies and their husbands who governed and funded the charitable institution (including William Hogarth and George Frideric Handel), those bringing children were invited to pick a ball from a bag. If they selected a black ball, they were escorted immediately from the premises; a white ball meant that the child was admitted, on the condition that they passed a medical examination; a red ball meant that if any of those offered a place failed this exam, the child had another chance at the lottery. Annual admission never exceeded two hundred, and three-quarters were turned away. By 1756, 1,500 children had been welcomed. Two-thirds of those died.

That year, the government extended financial help to the hospital on the condition that all children were accepted. During “the great reception,” as it was known, infants could be left in a basket at the hospital gates. Annual admissions exploded and fifteen thousand infants, from all over England and Wales, were admitted during the four years of the scheme. When the government program was discontinued after accusations that it encouraged vice and illegitimacy, children were admitted by written petition only in letters that usually named the mother. In rare cases, anonymity was guaranteed (for the illegitimate children of the upper classes) with a donation of one hundred pounds.

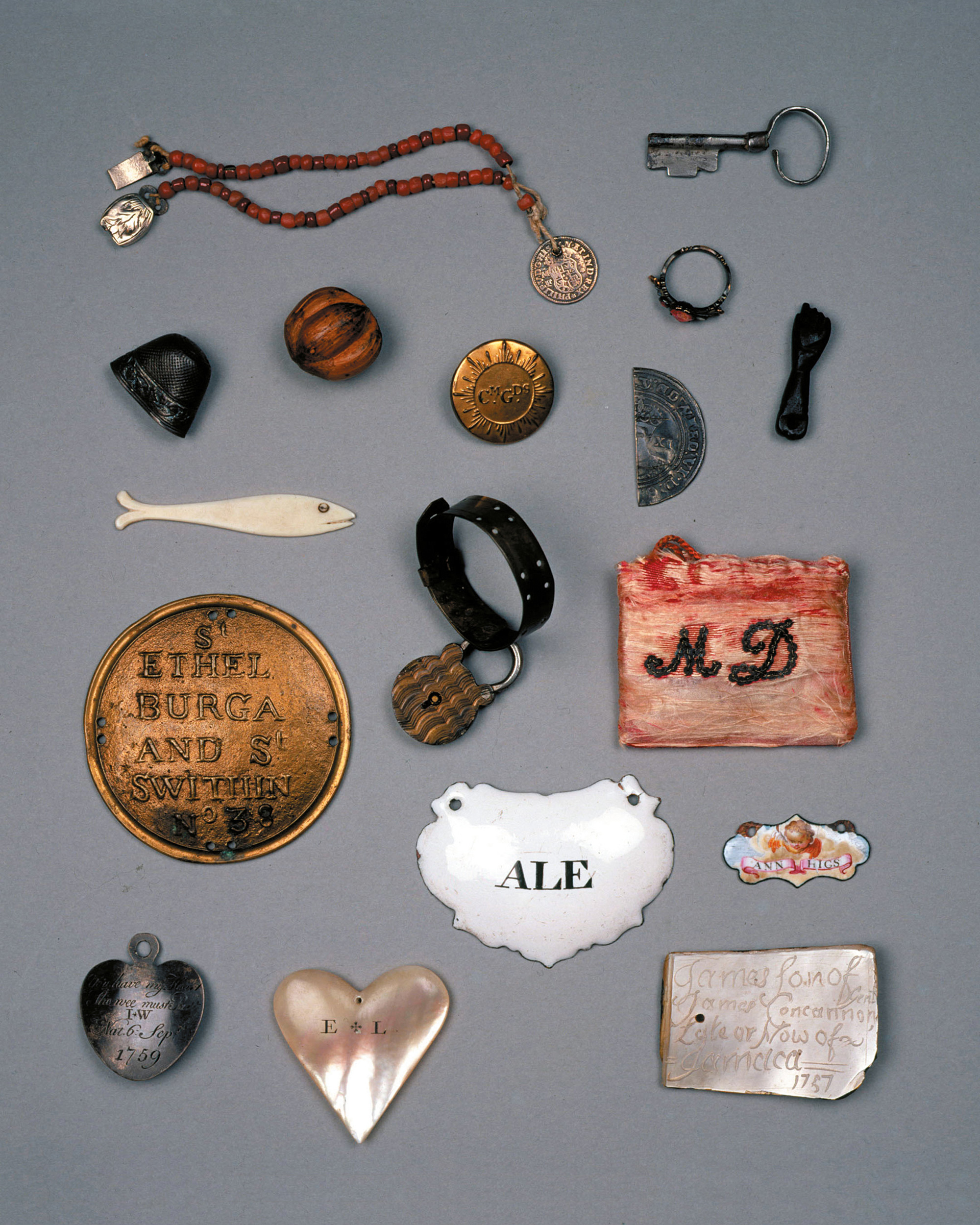

The announcement advertising the opening of the hospital stated: “If any peculiar marks are left with the child great care will be taken for their preservation.” As a result, many of the women left a “token” with their child—a medal, brooch, button, necklace, padlock, or other identifying object—which was bound with the folded billet, numbered, and sealed. These were identifiers, rather than gifts, things that the illiterate mothers could use to prove kinship if they wanted to reclaim their children if their circumstances changed. They often halved such tokens, which, when reunited, would prove a match.

These trinkets are transitional objects—severed umbilical cords—that embody the grief of separation. Few were ever able or wanted to get their offspring back: of the 16,282 children admitted between 1741 and 1760, only 152 were reclaimed (their mothers had to reimburse the hospital the cost of their care). The rest were eventually apprenticed to tradesmen, recruited to the army and navy, or, in the case of girls, entered into domestic service. With the ending of the “great reception”—and the requirement of petitions that identified the mother—as well as the issuing of receipts, the practice of supplying tokens dried up.

In the 1850s and 1860s, the sealed billets were opened and flattened into leather-bound “billet books.” The London Metropolitan Archives has nine hundred linear feet of records from the hospital, including this large inventory of admissions. The first billets were filled in completely by hand, but soon a printed form was generated to speed up the process. Before the infants were washed and outfitted with hospital-issued clothing, the reception officers recorded what they were wearing against a list of common attire (“Biggin,” “Forehead-Cloth,” “Head-Cloth,” “Long-Stay,” “Bibb,” and so on) and noted any distinguishing features (e.g., “a currant mark on the face”). Many tokens, including fabric cut from the children’s clothing that could later be matched with corresponding swatches given to the mothers, were pinned to the billets by their Victorian cataloguers, but bulkier items that couldn’t be so easily interleaved were removed.

These tokens were put on display in the hope of attracting more charitable donors to the hospital. The small, sentimental objects, which seem to evoke larger narratives of loss and grief, can still be seen in their glass vitrines in the Foundling Museum in Bloomsbury: a hazelnut; a coin with five holes; a brass cross; a crushed thimble; an ivory gambling token in the form of a fish; a penknife handle; a spyglass; a coral necklace; a hairpin; an amulet featuring a black hand. Each tells its secret story. A tiny ring, with a heart-shaped stone, is inscribed, “qui me neglige me perd,” which translates roughly as, “He who neglects me loses me.” A silver medal with a fleur-de-lis is engraved with the phrase “Innocency in Safety.” On a piece of mother-of-pearl is scratched, “James son of James Concannon Gent, late or now of Jamaca 1757.”

The tokens that were removed from their identifying packages themselves became orphans. Recently, researchers Janette Bright and Gillian Clark have, through painstaking detective work, managed to reunite some of them with the dossiers of the children to whom they belonged, repairing these lost links. They found that some of the billets referred to an accompanying token (“a peace of brase Portobello,” in the case of one commemorative medal depicting a naval victory), making this easy. On others, the object had left a faint imprint on the paper in which it was wrapped (as in the case of a padlock and cuff belonging to a boy admitted in 1757).

Nevertheless, some tokens remain missing pieces of a larger puzzle: an embroidered heart; an entry ticket to Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens; an enamel decorated with a cherub and marked with the name “Ann Higs.” Of these, the bottle tag that reads “ALE,” an unsentimental memento that conjures up images of Hogarth’s Gin Lane, is perhaps the most melancholy.

Christopher Turner is an editor of Cabinet. His book, Adventures in the Orgasmatron: How the Sexual Revolution Came To America, was recently published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in the US and by HarperCollins in the UK.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.