Practicing Restraint

The madness of the straitjacket

Will Wiles

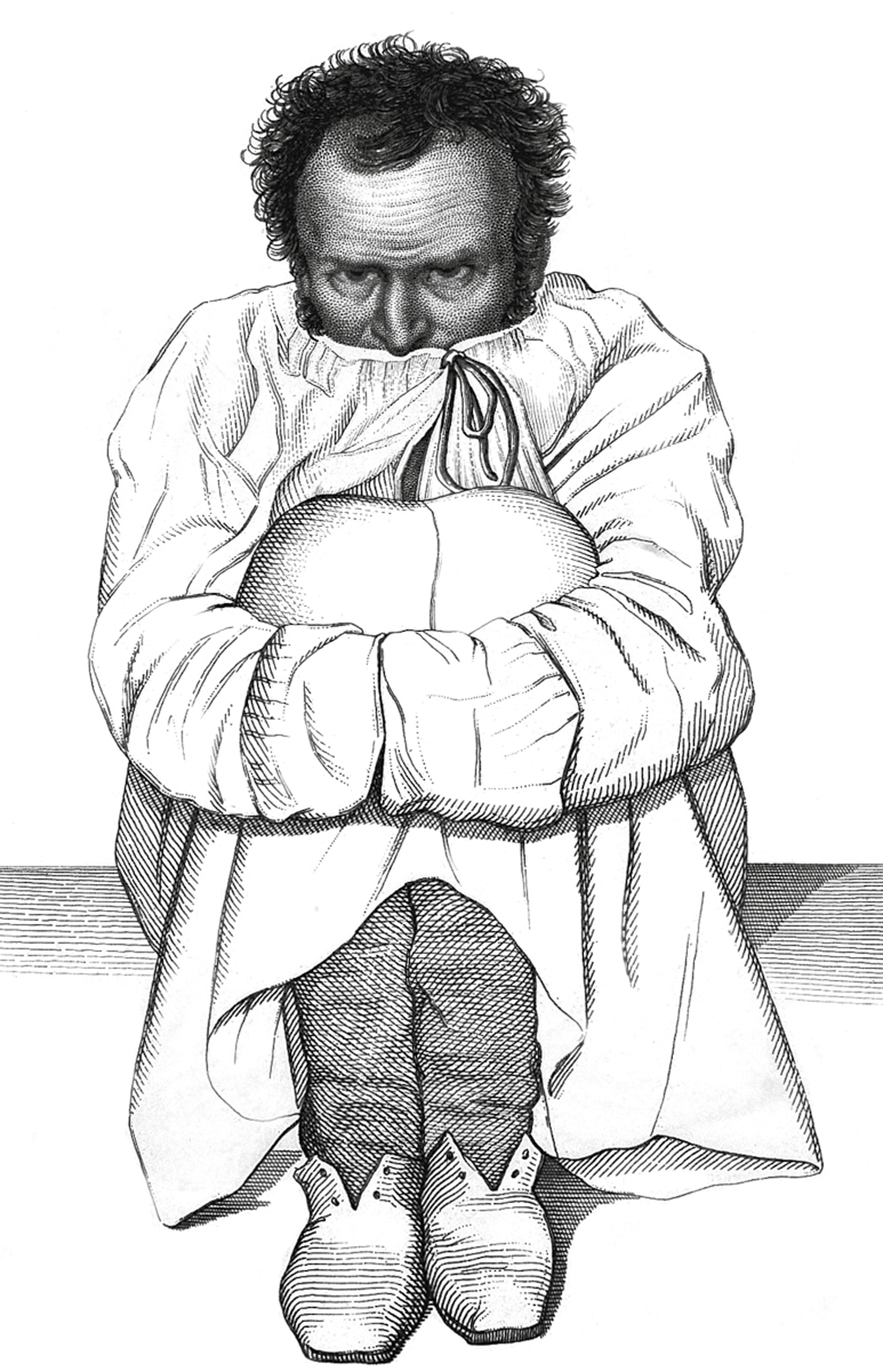

A grim exhibition might be made of inventions that are hailed as humanitarian, only to become symbols of inhumanity. Just as the guillotine was considered a great improvement on the axe, its contemporary, the straitjacket, had an early reputation for kindness as it replaced the manacles. When French physician Philippe Pinel and his assistant Jean-Baptiste Pussin freed the inmates of Paris’s Bicêtre and Salpêtrière asylums from their chains in 1795, he imposed the straitjacket instead. This he considered only the slightest curtailment of their freedom. “Forty wretched patients who groaned under the weight of the irons for varying numbers of years were set free in spite of all the apprehensions registered by the Central Bureau, and they were allowed to wander about freely in the courtyards simply with the movements of their arms restricted by a strait-jacket,” Pinel wrote in 1809.[1] Free, but in straitjackets.

But where had the liberating straitjacket, or camisole de force, come from? Michel Foucault and others credit it to an upholsterer named Guilleret employed at Bicêtre and date it to 1790. More recent historians of Bicêtre date it to 1770.[2] Certainly, numerous references to it can be found from years earlier than 1790. The earliest known description of the device is from the Irish doctor David Macbride, writing in 1772:

No small share of the management of mad people consists in hindering them to hurt themselves, or do mischief to other persons. It has sometimes been usual to chain and beat them, but this is both cruel and absurd; since the contrivance called the Strait Waistcoat answers every purpose of restraining the patients, without hurting them.

These waistcoats are made of ticken, or some such strong stuff; are open at the back, and laced on like a pair of stays; the sleeves are made tight, and so long as to cover the ends of the fingers, and are there drawn close with a string, like a purse, by which contrivance the patient has no power of using his fingers; and, when he is laid flat on his back in bed, and the arms brought across the chest, and fastened in that position, by tying the sleeve-strings fast around the waist, he has no power of his hands.[3]

More than a description, this is a glowing recommendation. And physician William Cullen, writing in Edinburgh in 1784, gives the straitjacket similar praise, and adds that it is a helpful therapeutic tool:

Restraining the anger and violence of madmen is always necessary for preventing their hurting themselves or others: But this restraint is also to be considered as a remedy. Angry passions are always rendered more violent by the indulgence of the impetuous motions they produce; and even in madmen the feeling of restraint will sometimes prevent the efforts which their passion would otherwise occasion. Restraint, therefore, is useful, and ought to be complete; but it should be executed in the easiest manner possible for the patient, and the strait waistcoat answers every purpose better than any other that has yet been thought of.[4]

Chains were brutal; the straitjacket was medical. But it could still be a punishment, even if it was a therapeutic punishment. Pinel refers to it as a punishment in his writings, and it was so feared by some of his charges that its mere mention could put a stop to bad behavior.[5]

But even the “humane” straitjacket soon had the shadow of obsolescence fall across it. Pinel and Pussin’s liberation of their patients was the first step in the emergence of the so-called “moral treatment”—a revolutionary new approach to mental illness which proposed that treating sufferers as people, rather than dangerous animals, would improve their condition. Through the first half of the nineteenth century, the moral treatment transformed conditions for mentally ill people and, by suggesting that their affliction was curable, laid the foundations for modern psychiatry. Progressive institutions tried to minimize all forms of corporal restraint. By 1840, inspectors from the New York state legislature reported from Bloomingdale Asylum that none of its patients were fettered, “even with straitjackets.”[6]

The straitjacket could have slipped into history as a medical curiosity. But it was far too useful for that—as a form of protective restraint, but more importantly as a method of punishment and a source of fear. This is the use that gives it such a strong presence in the cultural imagination; it is regarded, even today, with particular terror. “I had read with horror, since my imprisonment, of the camisole de force,” wrote an anonymous prisoner awaiting execution in 1839 France:

The camisole is a large vest of coarse cloth, open at the back, and closed in front,—like a coat reversed,—with long, tight sleeves, which hang down below the hands. It is fastened behind with straps and buckles; and at the end of the sleeves there are eyelet holes, through which a cord is tightly drawn, until they become like the mouth of a tied sack. Your arms are then bound one upon the other, and the cord is passed round your body and over your shoulders, when it is tied in a knot behind your back. In this guise you can just move your legs; but the most disagreeable part of the affair is, that you cannot find an easy position for sleeping. If you lie down on your side, the weight of your body soon cramps the arm; and, if on the back, the knot of the cord between the shoulders, and the leather straps and buckles, almost penetrate the flesh. I tried every position, and found the last the best; but the pain was so acute that I could not sleep.[7]

What makes the physical torment of the straitjacket worse are the perversities that surround it. A medicinal punishment is a queasy enough concept. And a device designed to protect the wearer from the consequences of derangement itself causes derangement. You Can’t Win, Jack Black’s 1926 autobiography of life in the hobo underworld, details the routine use of the straitjacket as a punishment in California’s San Quentin prison at the turn of the twentieth century. “I’ve got something now that will make you tough birds snitch on yourselves,” the warden crows when he acquires the jacket, a tribute to its power to sap the will. And as well as knowing of men being killed and maimed in the “San Quentin overcoat,” Black “saw the jacket making beasts of the convicts and brutes of their keepers.”[8] The straitjacket, originally devised to care for the insane, in fact drove the sane mad.

Michel Foucault describes this interaction between loss of liberty and loss of sanity in his History of Madness: “The disappearance of liberty, once a consequence of madness, now became its foundation, secret and essence.” And he uses the straitjacket to demonstrate this point. It is not an “absolute, punitive restriction” like the chain, but is designed to “progressively hinder movements as their violence increased.” From the 1850s to the 1870s, as the brief heyday of the moral treatment passed, the asylums filled to overcrowding and their role shifted from treatment to containment. In this context, the straitjacket was all too attractive to overstretched asylum-keepers with declining resources.

There, back on the ward, the jacket was discovered by Harry Houdini, who would do much to publicize the device through his escape act. On his 1894–1895 Canadian tour, the magician was invited to visit an asylum in Saint John, New Brunswick, by its keeper, a Dr. Steeves. In a padded cell, Houdini reported seeing “a maniac struggling on the canvas padded floor, rolling about and straining each and every muscle in a vain attempt to get his hands over his head and striving in every conceivable manner to free himself from his canvas restraint.” Houdini was deeply impressed:

Entranced, I watched the efforts of this man, whose struggle caused beads of perspiration to roll off him, and from where I stood, I noted that were he able to dislocate his arms at the shoulder joint, he would have been able to cause his restraint to become slack in certain parts allowing him to free his arms. But as it was that the straps were drawn tight, the more that he struggled, the tighter the restraint encircled him, and eventually he lay exhausted, panting, and powerless to move.

Previous to this incident I had seen and used various restraints such as insane restraint muffs, belts, bed-straps, etc., but this was the first time I saw a straitjacket, and it left so vivid an impression on my mind that I hardly slept that night, and in such moments as I slept, I saw nothing but straitjackets, maniacs and padded cells! In the wakeful part of the night, I wondered what the effect would be to an audience to have them see a man placed in a straitjacket and watch him force himself free therefrom.[9]

The next morning, Houdini asked to try the jacket for himself. It would become a trademark element of his escape act.

The straitjacket is terrible because despite the uses to which it was later put, the sickly odor of benevolence still lingers over it—it is still seen as a means to protect those placed in it from themselves. It implicates the wearer in their own plight in a way that the chain does not. It even turns the wearers’ own anatomy against them, binding them to themselves in a way that suggests swaddling, again reinforcing that sense of paternalist (or maternalist) tough love rather than simple oppression. And its long association with the treatment of madness marks the wearer as insane—a motif repeated over and over in the straitjacket’s appearance in film and television, where an unsuspecting but sane individual is tricked or forced into the straitjacket, and is then disbelieved by doctors and orderlies when he tries to explain his way out. And such confinement is particularly feared because, as well as being mistaken for being insane, the innocent wearer could be driven out of their mind by the experience. The straitjacket is madness.

- Philippe Pinel, Medico-Philosophical Treatise on Mental Alienation, Entirely Reworked and Extensively Expanded, Second Edition [1809], trans. Gordon Hickish, David Healy, and Louis C. Charland (Chichester: John Wiley & Sons, 2008), p. 78.

- Jean Delamare and Thérèse Delamare-Riche, Le Grand Renfermement: Histoire de l’hospice de Bicêtre 1657–1974 (Paris: Èditions Maloine, 1990), p. 49.

- David Macbride, A Methodical Introduction to the Theory and Practice of Physic (London: W. Strahan and T. Cadell, 1772). Macbride’s book was based on lectures given in the 1760s, which must cast some doubt on the Guilleret/1770 claim. Available at tinyurl.com/d4w5cjp. Accessed 21 June 2012.

- William Cullen, First Lines of the Practice of Physic [1784] (Edinburgh: Bell & Bradfute, and Adam Black, 1816), p. 196. Available at tinyurl.com/d33a953. Accessed 21 June 2012.

- Philippe Pinel, op. cit., p. 78.

- David J. Rothman, The Discovery of the Asylum (Boston: Little, Brown, & Company, 1971), p. 148.

- “The Last Days of a Republican Condemned to Death,” Bentley’s Miscellany, vol. 24 (London, 1848), pp. 108–109.

- Jack Black, You Can’t Win [1926] (San Francisco: AK Press, 2000), p. 241. For the history of the term “San Quentin overcoat,” see Carl Sifakis, The Encyclopedia of American Prisons (New York: Facts on File, Inc., 2003), p. 185.

- Walter B. Gibson and Morris N. Young, eds., Houdini on Magic (Mineola, NY: Dover Press, 1953), p. 9.

Will Wiles is an architecture and design writer based in London. His debut novel, Care of Wooden Floors, will be published in the US by Amazon/New Harvest in October 2012. He is working on a brief history of the straitjacket and a second novel.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.