The Republic of Letters: An Interview with Nancy Pope

Going through the mail

Joshua Bauchner and Nancy Pope

At Cabinet, we spend a significant amount of time thinking about the mail: Will a package with total dimensions just half an inch over the maximum for international first-class mail be rejected? Will our newly double-banded bundles of magazines pass the “perfect bundle” test for periodicals-class mail? We have developed an especially intimate relationship with the United States Postal Service, as the generally superb and deeply discounted periodicals class of mail is our lifeblood. In navigating the hairy ins and outs of the USPS, we made friends (our phenomenal daily letter carrier, Raymond Bullard) and enemies (the mysterious Anthony B. Street, overseer of no. 1 sacks at the Morgan Business Mail Entry Unit in Manhattan). Yet we remain, like most people, ignorant of and somewhat amazed by the actual functioning of the post. As Kafka wondered nearly a century ago, “How on earth did anyone get the idea that people can communicate with one another by letter!”

Perhaps because of the basic physical nature of the mail, the post and its workings seem largely intelligible, if not downright simple—especially contrasted with the electronic communication technology that followed it. One imagines the post working merely via a hands-across-the-world-type human chain. But it is precisely the seemingly simple nature of postal functions that obscures the complex logistics that actually ferry mail from person to person. Joshua Bauchner spoke to Nancy Pope, historian and curator at the Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum, about how the logistics of the postal system cut across transportation, technology, management, economics, the law, and beyond, and how it challenged those in charge of it to think in ways both tremendously pedestrian (how to convince people to use ZIP codes) and ambitiously radical (the penny post and the Universal Postal Union).

Cabinet: Let’s start with something very basic: When I send a hand-addressed letter from here in New York to a friend in Oakland, how does it get there? Why do letters go places when I put them in the mailbox?

Nancy Pope: Getting the mail from one place to another has four basic segments: acceptance, processing, transportation, and delivery. Acceptance can happen in your mailbox, in one of the on-street blue collection boxes, or at a local post office, and conveys your letter, via the local post office, to the nearest processing center; this still happens mostly by hand. The next two steps are really all a question of automation, as they have been since after the end of World War II. Processing comes down to machinery. Each of the three different types of mail—letters, packages, and flats, which include catalogues and magazines—has its own way through the system, its own machines. Your letter first goes through a culler, which separates the letters from the packages. It then enters a machine that does facing and canceling. The machine finds the stamp thanks to a phosphor in the stamp; it senses the phosphor, flips the envelope face up if necessary, cancels the stamp, and sends the letter on to a barcode machine, which will actually read the address, your handwriting. It takes a picture of your handwriting, compares it using OCR to a database of known addresses, and, once it makes a match, sprays a barcode onto the envelope. From then on, everything that happens to that letter happens because of the barcode.

The barcode encodes all sorts of information about that letter: Where and when it was deposited, what machine and facilities it has been through. But it also tells the next machine exactly where on the letter carrier’s route your friend’s building shows up—part of the barcode is an eleven-digit ZIP code, specific to the building. By the time the letter leaves a processing facility in New York to get on a plane—transportation—to go to Oakland, most of the work is done. In Oakland, another machine reads the barcode, identifies the appropriate carrier, route, and specific building, putting the letter with other items for that building in the correct place. The carrier grabs the envelopes, set up in order, and out the letter goes for delivery. At this point, flats have been sorted via their own system and integrated with the letters. Packages are still processed on their own.

What are the flaws that may cause this automated system to fail?

Red envelopes carry a small amount of phosphor that is similar to that of stamps, so red envelopes can confuse the facing-canceling machines and are kicked out to be faced by hand. This was more of a problem in the past, and the machines have improved in this respect. At this point, even if an envelope needs to be faced by hand, the machines are good enough to correctly identify and cancel the stamp. But Christmas and Valentine’s Day still pose a challenge to postal workers due to the extra red envelopes that need to be faced by hand.

The OCR technology is so good that very few letters fail to match the database of known addresses. With your friend’s name, street address, city, state, and ZIP, the machine only needs to make a likely match, as opposed to all other possible addresses, to barcode an envelope. If there is no match, the machine takes a picture of the address and sends it to be read by a human at the remote barcoding center in Utah. What’s amazing is that the machines process mail—read the address, spray the barcode, and correctly sort the envelope—at a rate of nine letters per second!

Now that the letter has arrived at my friend’s house, I want to go back in time and discuss the founding of the postal system in this country. Famously, Ben Franklin was the first postmaster general. But I assume there were prerevolutionary post services. How did colonial mail work and how did it transition into what was an early national system?

In the 1600s and 1700s, there wasn’t really a lot of need to communicate across colonies. People in Massachusetts really couldn’t care less what people in New York had to say—people were communicating with their home countries. It wasn’t until the late 1600s that the idea of a cross-colonial post came up, but initially the service was really, really slow. Across the early post roads—adapted from Indian trails—post riders would stop, chat, have lunch, spend the night somewhere. Speed was not an issue.

In the 1730s, the British name Ben Franklin co–postmaster general of the Crown Postal System, along with a fellow named William Hunter. Thinking that correspondence depends on reliably knowing what is going on as soon as possible, they initiate many new ideas, altering the post to feature security and maybe even speed. Primarily, this consists of improving conditions on post roads and of quality control of riders. As colonists begin to correspond more with each other, they start to foment a separate identity. This non-British identity is strengthened by other factors, and the colonies build toward revolution. The Crown Post takes to opening people’s mail; Franklin is fired, as he is a little too helpful to the colonists. The Continental Congress sets up the Constitutional Post, with Franklin as the postmaster general, which soon drives the British Crown Post out of business. If you had the choice of using a less-than-reliable service in which they might be opening your mail or a reliable service in which privacy is paramount, which one are you going to choose?

After the revolution, the Constitutional Post is codified into law by the postal acts of 1790, 1791, and 1792. The first two just affirm that the system works, we’re staying with it. The third enshrines two basics that dominate the new nation’s postal system in the nineteenth century: First, newspapers are to travel at seriously reduced rates to subscribers or free between publishers. Ensuring that information travels as cheaply and easily as possible is critical; without newspapers, it was felt, the new country could not effectively elect leaders and govern itself. So the privilege received by newspapers is basically self-preservation. Second, Congress has the right to establish post roads and post offices. At this point, post roads are the national artery of information, of newspapers; and they’re not just traveling between Boston and New York anymore. The 1792 act not only gives Congress permission to keep adding roads but encourages citizens to petition for new roads. And though this spurs a great debate between Jefferson and Madison—Jefferson argues that the right to establish post roads only allows the federal government to select from those already made—the federal government eventually takes responsibility for maintaining, expanding, and enhancing the nascent interstate transportation system.

In 1792, there are a little over 5,000 miles of post roads; by 1828, there are over 114,000 miles. The federal government has created a vast mass communication infrastructure—building roads, maintaining them by running stagecoaches, getting mail to everyone—not only in the original colonies but also in Kentucky, Vermont, Tennessee, and far western Pennsylvania. Today, in the era of “snail mail,” it’s hard to remember that the Post Office Department, for the majority of our history as a nation, equaled speed. There’s a wonderful quote from Amos Kendall, who was the postmaster general under Jackson: “No people appreciate economy in time more than those in the US.” We now equate information and speed, so it’s hard for us to remember that there was a time when these were distinct. The postal system was integral in establishing this concept, reinforcing it over and over. In the late 1700s and early 1800s, there were competing stagecoaches going over post roads; some of these were contracted to carry, in addition to passengers and private goods, the mail. Between Boston and New York, let’s say, there would be John’s Stage Line and Joe’s US> Mail Stage Line. Everybody who is booking passage for travel, is booking it on Joe’s US Mail Stage Line, because they know that has a schedule to keep and it will keep it. Whereas with John’s Stage Line, who knows? Information equals the post office, speed equals the post office, information equals speed.

Who is paying for the mail at this point?

That’s a problem. In the 1700s in general, but especially after 1792, newspapers were traveling for free or reduced rates—and that’s what was in the mail. If you were to break open any mailbag anywhere in the country, you would find newspapers. If you looked very carefully, you might find a letter. Letters were priced by distance as well as the number of sheets, making the rates astronomical for most people. Most letters were from members of Congress or presidents, due to their franking privilege; some were business letters. There was really no personal mail, it was too expensive. In the early US, there was, on average, one piece of personal mail per person per year.

And often, with what personal mail there was, senders and recipients escaped paying by establishing a code, as payment could be made by either sender or recipient—for instance, an eye drawn on the outside or a couple of extra letters in the recipient’s name. When you picked up the letter at the post office, you saw the code, and it told you, “Everything’s OK here.” You knew the message without opening the letter and handed it back to the postmaster, saying, “I don’t want this. I’m not paying for this.” That’s not unusual, there was a lot of that going on. Therefore very little mail is producing revenue, and the government is paying for the system. This continues for many decades.

In 1828, the Post Office Department is created; it becomes a cabinet-level position under Andrew Jackson. There are lots of changes, yet none affect how mail is paid for. In the 1830s, there is the penny post revolution in the United Kingdom; the US looks at it and says, “That can never work here, we’re too big.” By the 1840s, postage rates continue to be ridiculously high; people want to use the mail, but they can’t, and the postal system is not getting paid for the letters it does carry. We adopt two main ideas from the British post, which is advancing rapidly using the ideas of postal reformer Rowland Hill: first, how one pays for a letter, and second, what one pays for a letter.

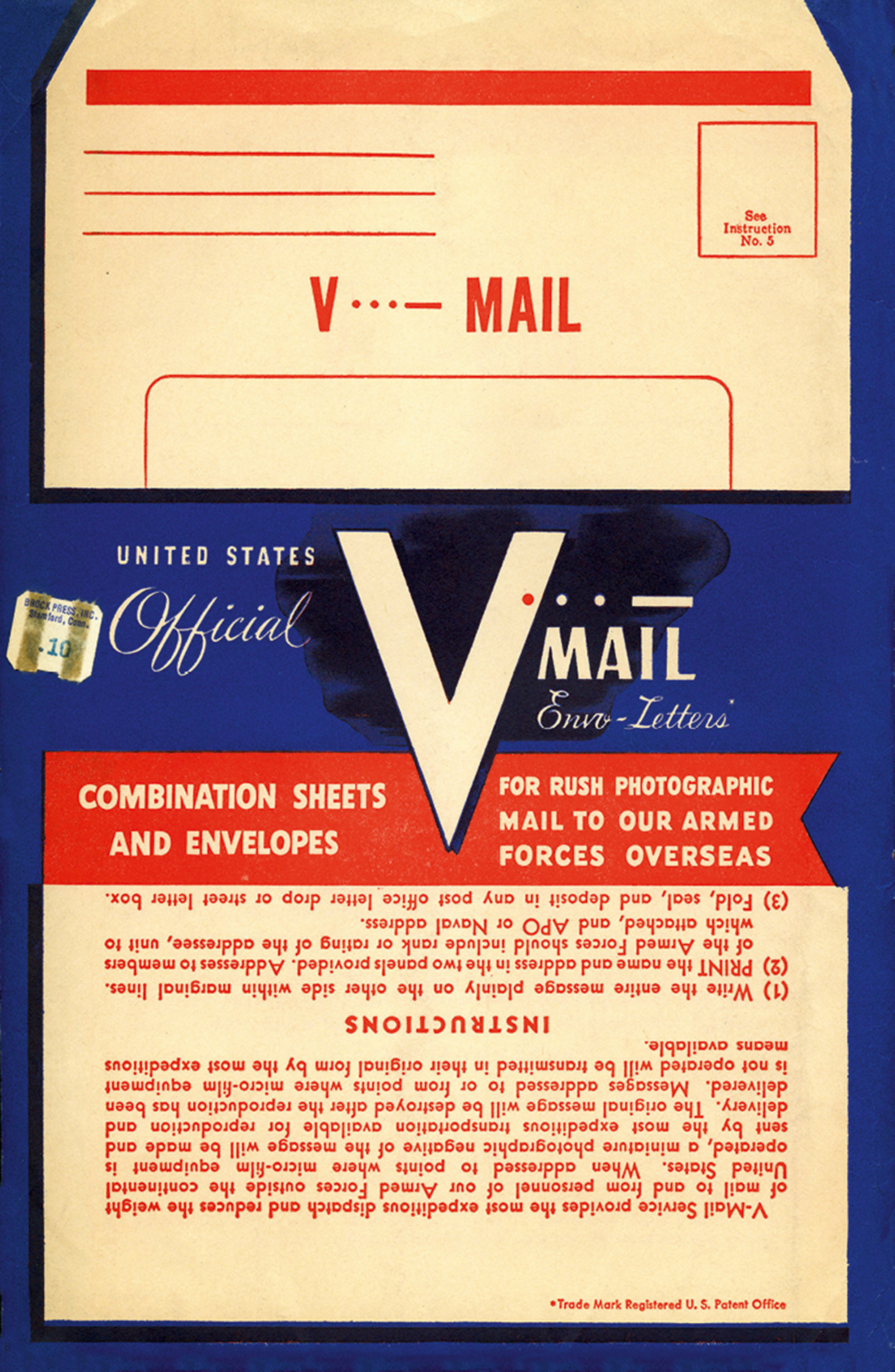

In 1840, Hill adopts, with significant modification, this wonderful idea: something you glue to the envelope and have to pay for first—the stamp. The US takes this idea in 1847 and creates two stamps, five cents and ten cents, but using them is only a suggestion. Many people do use stamps, but not enough, and in 1855, usage is made mandatory. More important, in 1851, the government starts to consider rates as an issue—maybe if we make mail more affordable, more people will use it. Revolutionary idea! So they begin to cut the rates—now calculated by weight and distance rather than number of sheets—and more people begin to use the mail. More people are being schooled in America; literacy is becoming the norm rather than a rarity; people can read and write and afford to send letters. And they start doing it. By the Civil War, when you have families separated, the post has exploded and people are sending letters all over the place. It’s the dual idea that you have to pay the postage first, so the postal system knows it’s paid for, but that postage is also now affordable.

This raises the question of when different classes or types of mail began. At what point do the distinct rates for newspapers and letters evolve into classes? And when do packages come into the mix?

This question arises in the mid-1800s as the printing industry is rapidly developing and more periodicals are appearing. Is a periodical a letter? Is it a newspaper? Is it a book? Postmasters don’t know how to charge for these things based on the classic letter-or-nonletter system. Classes of mail are set up to distinguish how mail should be priced. In 1863, the post office initiates a system of first-, second-, and third-class mail. Letters are first class, as they still are today. Second class is perpetually debated: is it newspapers, is it a bound piece of information, is it a bound piece of information that only weighs a certain amount or has so many pages in it, is it bound and foldable? Eventually, newspapers and periodicals are classed together as second class, separately from books. And the new third class is for the bourgeoning book and pamphlet trade. Each year, the postmaster general would publish a report that set the rates for each class and established what the difference was between a bound periodical and a book. And each year, some publishers would try to take advantage of the cheaper rates, whether by binding the book differently or issuing a book in four issues, so that it was a serial.

Parcel post is a separate issue. Parcels went through the mail, but it wasn’t a dedicated service; in the second half of the nineteenth century there was a four-pound limit on parcels. As early as the 1870s, farmers are trying to get into the postal system via a dedicated parcel post because they have to send their goods to market by express companies. The express companies have pretty much split the US into monopolized little fiefdoms and control the rates in that area. There are no national standards and rates are almost set on a whim—if it’s a great year for apples, the farmer arrives to mail his apples to the market and learns that the rate for apples is a dollar more than it was a year ago. But the express companies have some very influential members on their boards, members who are also congressmen. They keep parcel post out of the post office until January 1913.

Are these express services the precursors of today’s UPS and FedEx? Or do they die out?

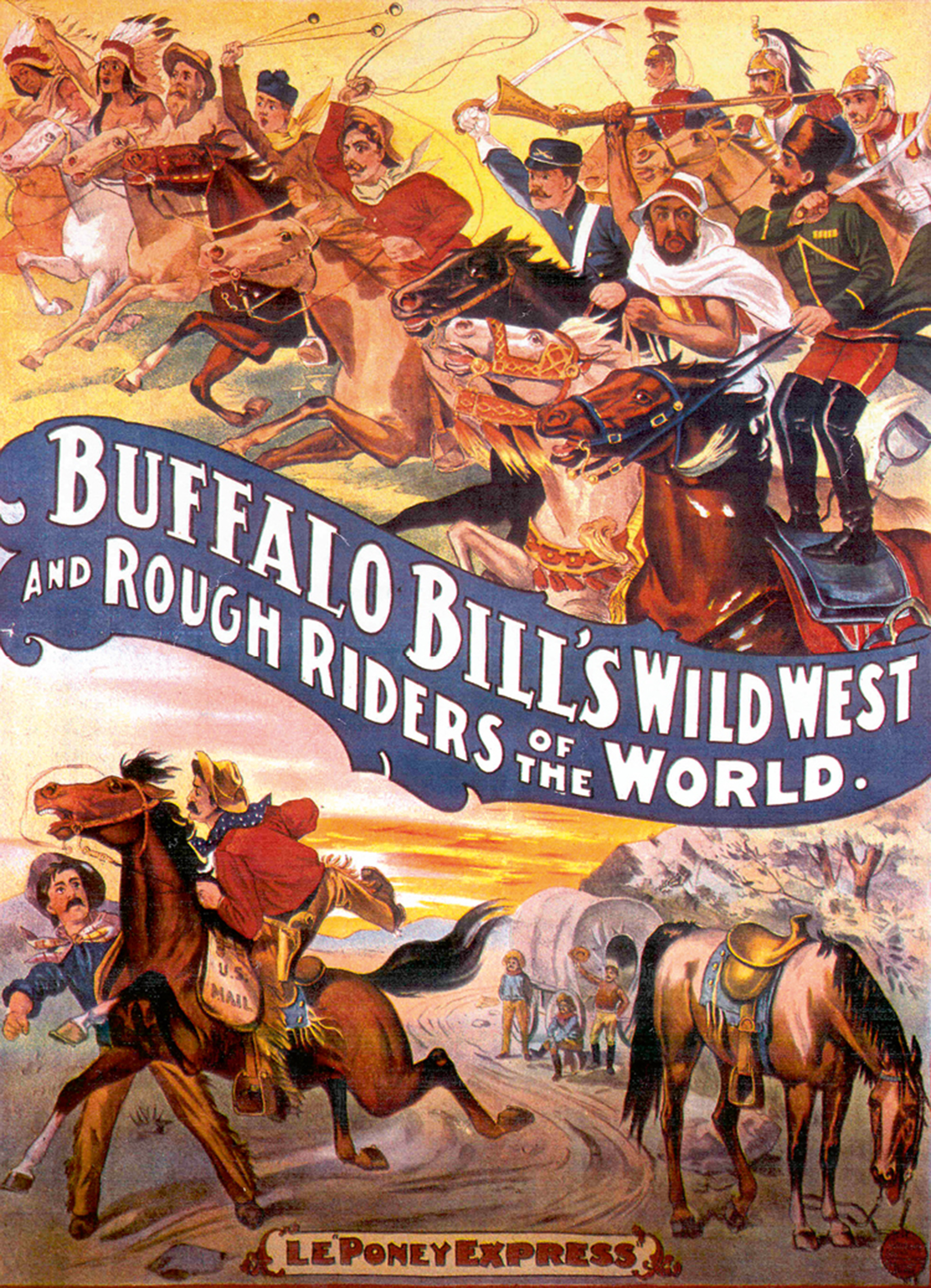

Some of them die, some evolve. Wells Fargo is one that evolved very well. Ultimately, the most successful of them were integral to the development of postal routes via the “star routes.” By the 1840s, especially after gold is found in California, the post office begins to ask how to get mail to all these far-flung territories. From the rapidly growing interior to the Pacific Coast—these settlers are being enticed and learning, along with the rest of the country, to use the national mail system. Should the Post Office Department hire workers to transport the mail? Or should it contract with somebody who might already be running a stage line?

They settle on contracts in 1845—though not just for stagecoach lines, but also railways and steamboats. Eventually they contract companies with mules to go to the bottom of the Grand Canyon and some with dogsleds for Alaska. This system, with bags of mail transferred to a contracted individual or company for point-to-point movement, was intended to ensure the security, celerity, and certainty of the mail. Instead of writing those three terms when it came to evaluating a route, clerks used three asterisks, which resulted in that service being known as a star route. Wells Fargo and other express companies that managed to get these contracts did quite well.

But were they actually delivering this stamped mail? Or did the post office maintain a monopoly on delivery?

In the 1840s, there was an explosion of local posts, where companies set up their own postal systems within a city. Rarely were they intercity. All these different companies basically said, “We’re going to carry letter mail and maybe even issue our own stamps.” This leads Congress to legislate that the post office does have a monopoly over letter mail, later reinforced by a series of court cases. It doesn’t define a monopoly over other types of mail, hence the package-delivery companies. Moreover, it’s only later that the post office also receives a monopoly on delivery mailboxes. When the star routes begin, there are no mailboxes or mail slots—home delivery is not yet standard.

When did these hallmarks of the post—the blue on-street mailbox, the personal mailbox at the end of the driveway, and a mail slot on the front door of a townhouse—come into being as we know them now?

In the 1850s, along with the moves to reduce the cost of sending mail, the postal system wants to make it easier to use the mail. I can go to the post office and buy ten stamps, but do I have to go back every time I want to mail one of those letters? In 1855, the post office sets up the first of these little collection boxes, and it was very little. The boxes were attached to lampposts, and people could deposit letters into them with the understanding that postal employees would come around every once in a while, take all the letters out, and bring them back to the post office. It’s only with the advent of parcel post, beginning in 1913, that the collection box separates from the lamppost. At first these four-footed repositories were a deep olive green, as that was the postal color scheme; they only turn blue in the mid-twentieth century.

City delivery starts during the Civil War in the northern cities. Instead of having to go to the post office to pick up your mail or, if you have the ability, sending someone to pick it up for you, you could actually have the mail delivered to your home. Radical concept. It grows quickly after the war and Reconstruction. But all these new letter carriers go up to each home and knock on the door—yes, the postman did ring twice. If no one answered, the carrier just went to the next house and came back the next day with twice as much mail. In the meantime, in 1896, the Post Office Department has started what they call “rural free delivery.” Same concept: bring the mail to the person. But in this instance, the houses are spread far apart and the front door may be a mile away from the road. The solution is a receptacle right at the edge of the road for your mail. The concept of leaving mail is already there, though only in rural areas. The postmaster general looks at this and decides to try it in the city.

In the first decade of the 1900s, the post office requests that homes install a mail slot in their doors or a mailbox outside. Some people do, some people don’t. In 1916, the post office asks manufacturers to produce prototype mailboxes for official approval based on which are the sturdiest, which won’t let the bad weather in, and so on. Hundreds of boxes are sent in; there are only six that end up making the cut and are put into production. By 1923, mailboxes or mail slots are required by law for home delivery.

How did the railway mail service work? I have an image in my mind, mostly from westerns, of intrepid clerks valiantly hanging mailbags out of a train car to be grabbed by metal hooks at small depots on the frontier. Of course, they’re also wrangling with gangs and other such undesirables.

“Mail on the fly,” as it was called, and the mail cranes are a great story—again, the concept is to get mail to everybody. From 1863 to 1977, railway mail was the spine of the whole service. This decentralized everything, with sorting happening not in a central post office in a city but on the trains en route. This gets mail to everyone, and quickly. The Post Office Department didn’t own the railways—it only leased cars or contracted them—so they couldn’t tell the trains where to stop. To get the mail to every town that wasn’t a stop, they set up mail on the fly. These big old leather and canvas mailbags would hang from a crane at a depot; with the train whizzing down the track, the clerk would set out an iron bar, which grabbed the mailbag from the crane. At the same time, he had to keep the on-train mailbag ready to be literally kicked out for that town. The clerks talk about being able to tell at night when you are coming up to a crane just by the feel of the train, by the curves and the speed—they were very proud of that.

A central point of the logistics of the post was the clerk’s memory. The clerks had to know thousands of cities, towns, addresses, and train schedules, so they could sort mail to be taken once they arrived at the next station—not only to that station for the local area but to another train for destinations afield of the main trunk route. If I’m sorting mail between Cleveland and Chicago, I have to know every stop between those cities, addresses in Chicago, and the trains that I’m going to intercept at any particular stop along the way.

These guys were tested every year. If they did not test at 97 percent correct each time, they had to test again or they were out. There was a postal clerk in the late 1800s named Frank H. Galbraith who was a bit of an artist. He took maps of Minnesota, Iowa, Nebraska, and a few other midwestern states, and next to the names of all the towns he drew images that reflected the names. So for Lincoln, an image of Lincoln; for Bell, an image of a bell. You name the town, he had an image for it. And he rented these out to other clerks to use as memory aids.

Later, airmail pilots pioneered aerial mapping and manuals. The second assistant postmaster general, Otto Praeger, put out directions in 1921 that were fairly vague: “Cleveland to Chicago … [Mile] 172. Hamilton. - Two miles north of course and 4 miles north of Bryan. On the extreme south end of irregular-shaped lake. The Wabash Railroad runs to the south of Hamilton. By keeping the Wabash Railroad in sight for the next 125 miles, You will come in sight of Lake Michigan.” A fellow named Elrey B. Jeppesen wrote down better instructions on how to approach an airfield, as nobody had done that. He started writing these down in little black books and selling them to other pilots. And now it’s Jeppesen, a massive company of international aeronautical navigation.

Airmail also followed railway mail in trying to replicate mail on the fly. In the 1930s, a dentist named Lytle Adams from Pennsylvania tried an experiment: A mailbag was hoisted on a cord between two goal posts. The plane came down with a big hook to catch the mail. It was supposed to provide airmail for towns that didn’t have a municipal airport. The Post Office Department never bought it, though the army and air force were very interested in it because they thought the idea might be good for picking up people who were downed behind enemy lines.

Did it ever work out that way?

We have film footage that shows them testing it. They tested it with a sheep first—the animal did not make it.

Did they ever try the reverse of that, dropping mail out of planes, with parachutes?

The dentist Adams did—not with parachutes, but in big orange rubberized canisters. It was tried from 1936 to 1938, but never made it out of Pennsylvania and West Virginia.

As you noted, the colonial system began as an international system, and some of its advances were clearly in lockstep with those in the rest of the world. How does international mail work given all these later changes to domestic service?

By the time of the Civil War, the US is sending mail all over the place. We’ve been a nation of immigrants since the colonial era, but by the 1850s, we’re beginning to be a nation of immigrants from different countries. These new immigrants are writing home. But at this point, international mail is a mess: Let’s say I’m a just-arrived German immigrant, and I’m in Pennsylvania and want to send a letter back to my family. I have to pay US postage to get it to the ship, I have to pay postage for the ship—and that varies depending on the ship and the route—and I have to pay German postage. When I go to the post office, the clerk goes nuts trying to figure out the total postage—if he gets it wrong, that letter could be rejected. It may be rejected in Germany, by the ship. Who knows?

In 1874, a group of countries—European countries, plus the US and Egypt—get together in Bern and create the General Postal Union, which agrees to meet every four years. Together, they create “a single postal territory for the reciprocal exchange of correspondence between post offices.” A single postal territory—so Germany and the US are now no longer Germany and the US. They are one international postal system. So when I, the German immigrant, want to send the letter to my mother, all I have to do is pay the international rate, which is set by the local country. I pay the US for an international-rate stamp; that stamp goes on the letter; the letter goes to Germany; they don’t say, “There’s no German stamp on this,” and reject it; they say, “This letter comes from the US, part of the General Postal Union, we’ll take it!”

The 1878 meeting is key: the name changes to the Universal Postal Union and they decide to color code everything; blue becomes the color for international letter postage. Furthermore in 1878, they acknowledge international money orders, which originated in the US in 1863 due to the war, and create an international parcel post. This is especially weird in the US, which didn’t have its own parcel post; if you were sending a package within the US, you were still limited to four pounds. But if you were sending a package internationally, you had up to eleven pounds.

How did the rates actually get set for international mail?

The General Postal Union first agrees on fifteen Swiss centimes. Though the members agree that this is what the rate should be, each country is allowed to raise or lower the rate based on its need. For decades, it was just you pay for your letters at your rate, we’ll pay for ours at our rate, and we all agree that everything’s well. This system was simple and elegant and lasted until 1969. After a while, poorer countries start to notice they are delivering lots of mail from the US, but they are not sending out that much. They are not taking in as much postage as the work they are doing, in essence.

So the Universal Postal Union, now part of the UN, agrees to establish a system of terminal dues. Basically, at the end of a year, one member country pays another country a fee based on the difference in weight of total mail sent between the two; if the US sends forty-five thousand more pounds of mail to Brazil than it receives from Brazil, it pays a fee based on that amount. Eventually, in 1991, this is replaced by the threshold system, which is more or less the same but splits mail into more than one class. There is a base threshold of 150 metric tons. If either of two countries sends more than the threshold to the other country, the end-of-year fee is based on weight and class of the mail sent. If the threshold is not met, the old single-rate system remains. On top of this, there are a multitude of treaties between specific countries that supersede the general Universal Postal Union agreement. All the agreements though are basically based on the weight difference and favor the country that’s doing the work.

At Cabinet, addressing international mail has always been a challenge, attempting to balance what the USPS wants for outgoing international mail and what will be a readable address upon receipt. One particular quirk that always intrigued me was the use of “virtual postal towns” in the United Kingdom by the Royal Mail. At some point in the last twenty years, Royal Mail changed its addressing hygiene so that only a postal town and postal code is necessary, no county name. But in the changeover from the old form—town, county—some new “town” designations were created that do not correspond to local usage or all but the most detailed maps. If you try to validate an old-form address on the Royal Mail website, it may well return a totally different town name, with no county. It seems like an interesting challenge for a national postal system to change address hygiene on a major scale.

We’ve done that twice in the US. Once was in 1893, when the government was looking into the standardization of everything, and the idea of town names became an issue. The Post Office Department was part of the government entity ruling on how you should spell the name of your town: Is your town Leesburgh with an h? Nope, all the h’s are going from burgs. Is your town Pittsburgh with an h on the end? OK, your h can stay because you are Pittsburgh. Is your town Belle Ville, two words? Now it’s Belleville, one word.

But the big one was ZIP codes in 1963. There are hysterical videos from the campaign to promote ZIP code usage, including one with a folk group called the Swingin’ 6 singing the merits of ZIP codes. Ethel Merman sang the ZIP codes song to the tune of “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah.” The postal system did everything it could do to convince people that memorizing five numbers would not kill them. It was the same time as the introduction of area codes and the growing use of social security numbers as an all-purpose identification number and there are lots of editorials from the 1960s written by people afraid that we are being turned into numbers. Of course, because it is the Cold War, you have a wonderful subset of people saying that not only are we being turned into numbers but it’s a communist plot! The ZIP code was up against a lot of resistance.

Not only do you have to remember your five numbers, but the five numbers of everyone you are corresponding with? That’s a lot of bother. So the campaign was pretty intense over about a decade: The post office sent free cards that you could send through the mail to get the ZIP code for any address. There were phone numbers to call to get ZIP codes. For personal correspondence, the whole campaign centered on speed—use ZIP codes, your letters arrive faster. For business, it was all about the money—use ZIP codes, get lower rates.

As far as I can tell, ZIP codes are more specific than either city or state, so why are city and state still used as part of addressing?

They don’t have to be. Logistically it doesn’t matter, it’s just our tendency. In the old days, you could send a letter to “John James, Massachusetts,” and it got there. Now, all you need is that code at the bottom—not the five-digit, nine-digit, or even eleven-digit ZIP, but the new Intelligent Mail barcode number—to get a letter to someone. But who is going to do that? People get very, very upset when the USPS closes a post office; that cancellation mark that has a town name and zip code, that’s identity! People like and need the address; the numbers help it get there, but the address lets a human know where a letter is going.

Nancy Pope has worked with the Smithsonian’s postal history collection since 1984 and curated the opening exhibits for the National Postal Museum in 1993. Her most recent exhibit, “Systems at Work,” which opened in December 2011, examines the evolution of mail processing in the US.

Joshua Bauchner, a former associate editor at Cabinet, is a freelance editor and writer living in Brooklyn. He is currently working on a project about waiting in line.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.