The Living Lighthouse

The loneliest tree

Janet Connelly

In May of 1939, a French army officer named Michel Lesourd was traveling in the Saharan region of northeast Niger known as the Ténéré and filed a dispatch about a solitary tree he visited along a route used by Touareg salt trade caravans:

One must see the tree to believe its existence. What is its secret? How can it still be living in spite of the multitudes of camels which trample at its sides? How … does not a lost camel eat its leaves and thorns? Why don’t the numerous Touareg leading the salt caravans cut its branches to make fires to brew their tea? The only answer is that the tree is taboo and considered as such by the caravaniers. There is a kind of superstition, a tribal order which is always respected. Each year [caravans] gather round the Tree before facing the crossing of the Ténéré. The Acacia has become a living lighthouse; it is the first or the last landmark for the azalai leaving Agadez for Bilma, or returning.[1]

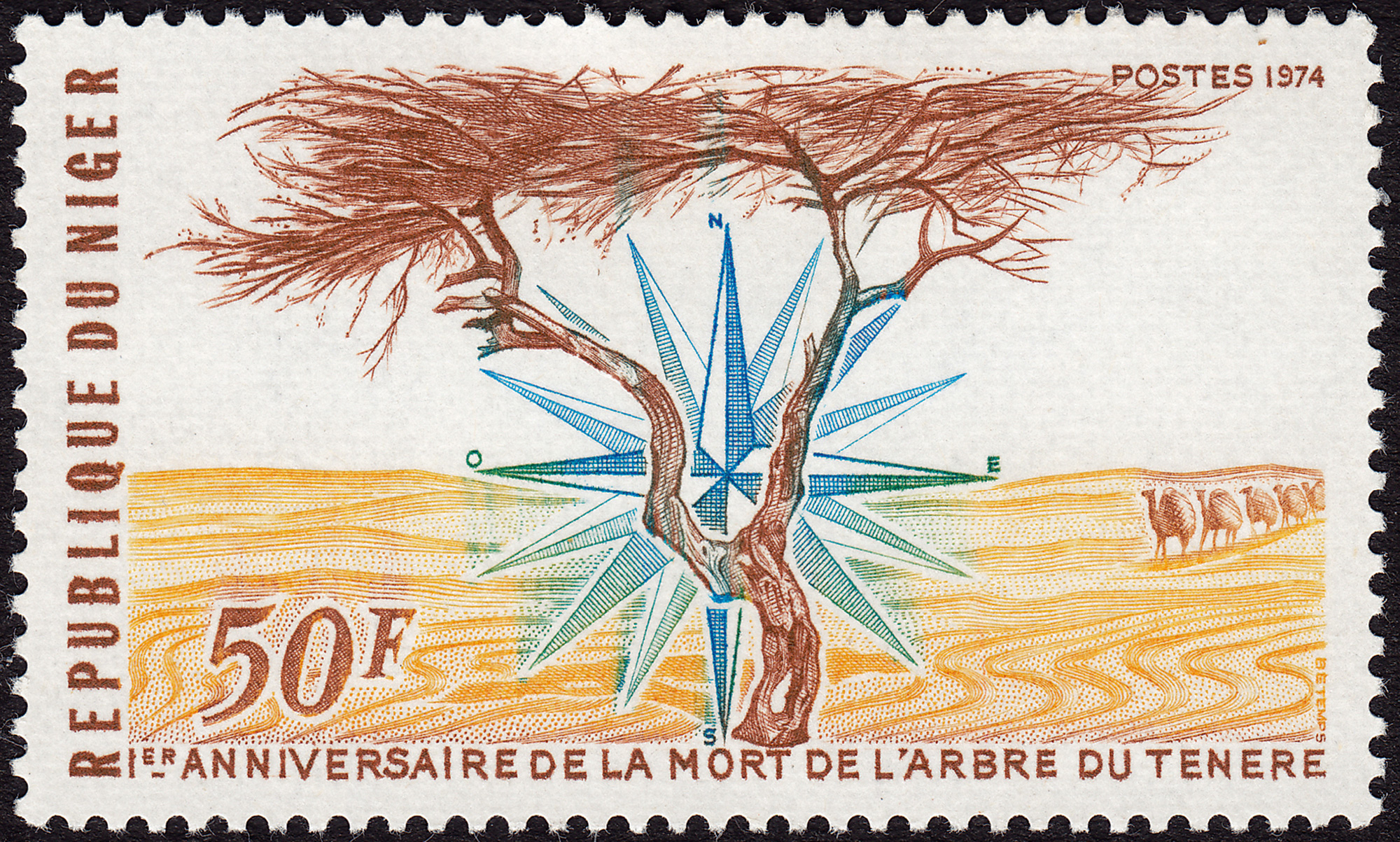

Lesourd had come to the area, in French-administered West Africa, to check on the progress being made on a well being dug there. Chief Sargent Lamotte, the project manager, had directed his crew to dig to a depth of one hundred feet, where water had finally begun to seep; there, Lesourd reported, at the surface of the water table, the roots of the acacia could be seen. It’s hardly surprising that the tree should have to go so deep to find water. The Ténéré, from a Touareg word for wilderness, is a notoriously inhospitable swath of sand dunes more than 150,000 square miles in size. Receiving roughly an inch of rain annually, the area is virtually unpopulated—by humans, fauna, or flora. L’Arbre du Ténéré, as the French called the acacia, was the only tree in a 250-square-mile area and, like l’Arbre Perdu (The Lost Tree, today known as l’arbre de Thierry Sabine, after the founder of the Paris–Dakar rally), was a sufficiently significant landmark on the empty plain of the Ténéré that it was shown on very large-scale maps of the area, despite being only a dozen or so feet tall.

Though the Tree of Ténéré guided generations of camel-riding traders on their route between Agadez and Bilma, it fared less well as modernity crept closer to this remote zone. The French ethnographer Henri Lhote first commented on the tree on a journey through the area in 1934, but on a return trip in 1959 he discovered its condition severely diminished: “Before, this tree was green and with flowers; now it is a colorless thorn tree and naked. I cannot recognize it—it had two very distinct trunks. Now there is only one, with a stump on the side ... What has happened to this unhappy tree? Simply, a lorry going to Bilma has struck it.”[2] Post-1959 images of the tree depict a gnarled yet resolute survivor, but less than a decade-and-a-half later another vehicular mishap would prove fatal for the tree, when in 1973 an allegedly intoxicated Libyan truck driver collided with it and killed it. The remains of the tree—which was estimated to be some three hundred years old—were taken to the Nigerien capital Niamey, where they today are displayed in a specially constructed gazebo on the grounds of the national museum. Meanwhile, at the original site of the tree in the Ténéré, an anonymous artist erected a memorial sculpture where it once stood, a totem of sorts that still attracts visitors to this desolate destination.

- Translation at the153club.org/tenere2.html [link defunct—Eds.].

- Translation at the153club.org/tenere.html [link defunct—Eds.].

Janet Connelly is a writer and driving instructor based in Brooklyn and Agadez, Niger.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.