Leftovers / Cephalophoric Reason

Head cases

Eigil Zu Tage-Ravn

“Leftovers” is a column that investigates the cultural significance of detritus.

Some of your readers will no doubt be familiar with the work of the great French folklorist Émile Nourry (1870–1935), the author of more than a dozen learned volumes and perhaps a hundred articles dealing with many fascinating problems in textual transmission, oral history, cultic paganism, and critical philology. A student of Émile Durkheim, Nourry carved out an idiosyncratic place for himself in the intellectual life of Paris before World War II: he founded his own press, and traded in rare books; as a gentleman-scholar, he rose to the presidency of the French society for folklore studies (a discipline whose breach-birth from the matrix of anthropology he arguably midwifed); and, writing under the pseudonym Pierre Saintyves, he gave the world thoughtful essays on the notorious dog-saint Guinefort, the mythic origins of various French surnames, the jackal-headed Egyptian demigod Anubis, and a host of other curious topics.

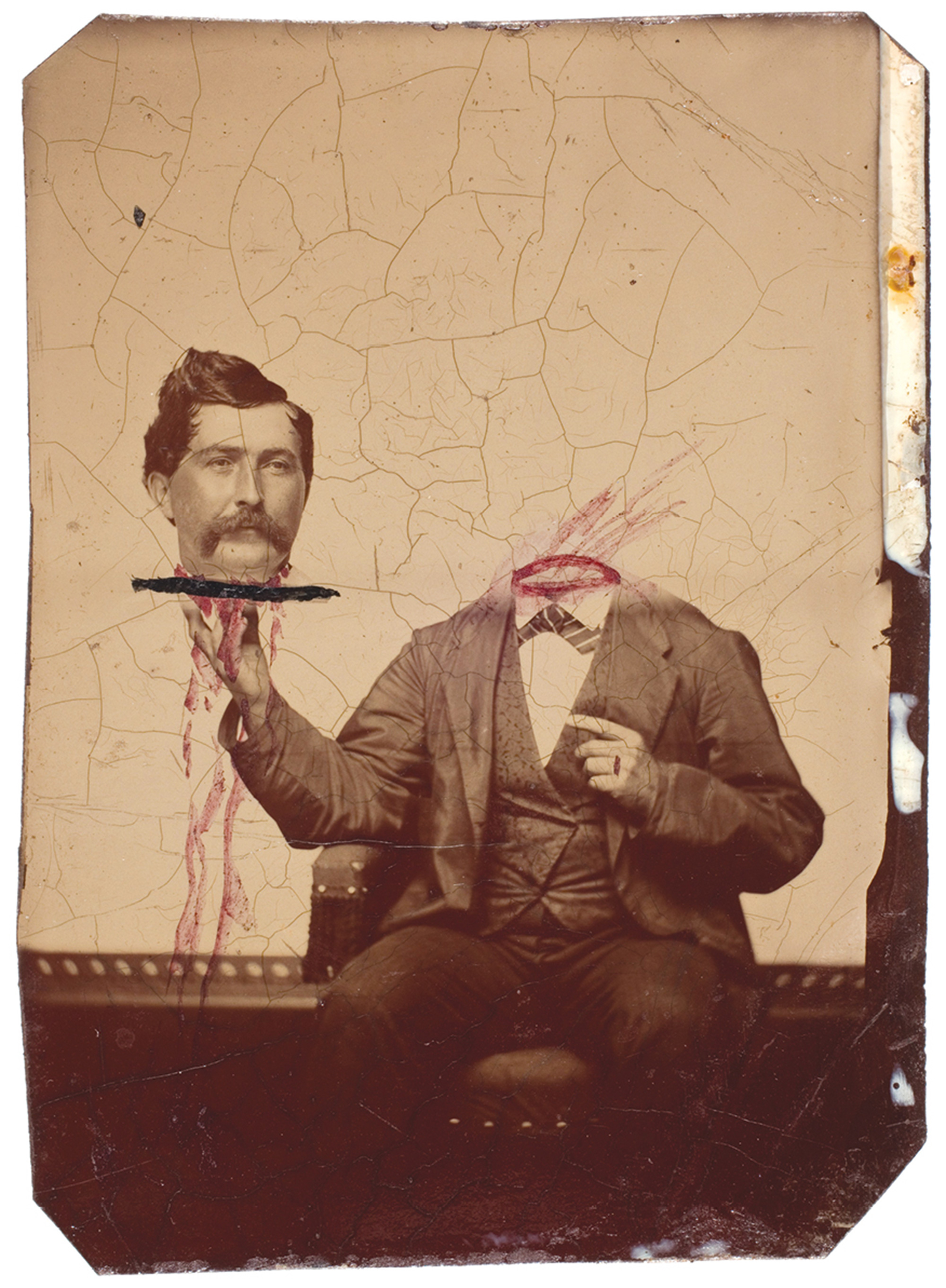

One can hardly think of a better example of Nourry’s idiosyncratic diligence than his exhaustive “Les saints céphalophores,” seventy-three closely researched pages documenting, in old French and Latin sources, more than 120 instances of saints engaging in “cephalophory”—i.e., carrying their own severed heads.[1] Paradigmatic here, of course, is the legend of Saint Denis (who after his decapitation reportedly walked, head in hand, to the top of Montmartre, where he sited his own grave). As Saintyves/Nourry impressively demonstrated in this classic piece of scholarship, a deep dive into the Christian hagiographies yielded many less familiar accounts of martyrs taking up their heads, addressing crowds, and moving about the world. Secular-literary treatments of the same phenomenon play a prominent role in the Arthurian tale of Gawain and the Green Knight and in canto twenty-eight of Dante’s Inferno (where, memorably, a character in the eighth circle of hell addresses Virgil and the pilgrim from a head that dangles lantern-like from his own hand). Related classical allusions appear in Homer and in the Orphean tradition (though these have more to do with loose heads that talk, rather than with cephalophory per se, where it is the carrying of the head that is specifically required—the term having its roots in the Greek for “head” and “to bear”).

I note with satisfaction that cephalophoric situations have of late come back into vogue as a topic of scholarly interest.[2] And it is in this context that I write to announce what would seem to be an important discovery.