Monster Wreck

The Crash at Crush

Will Wiles

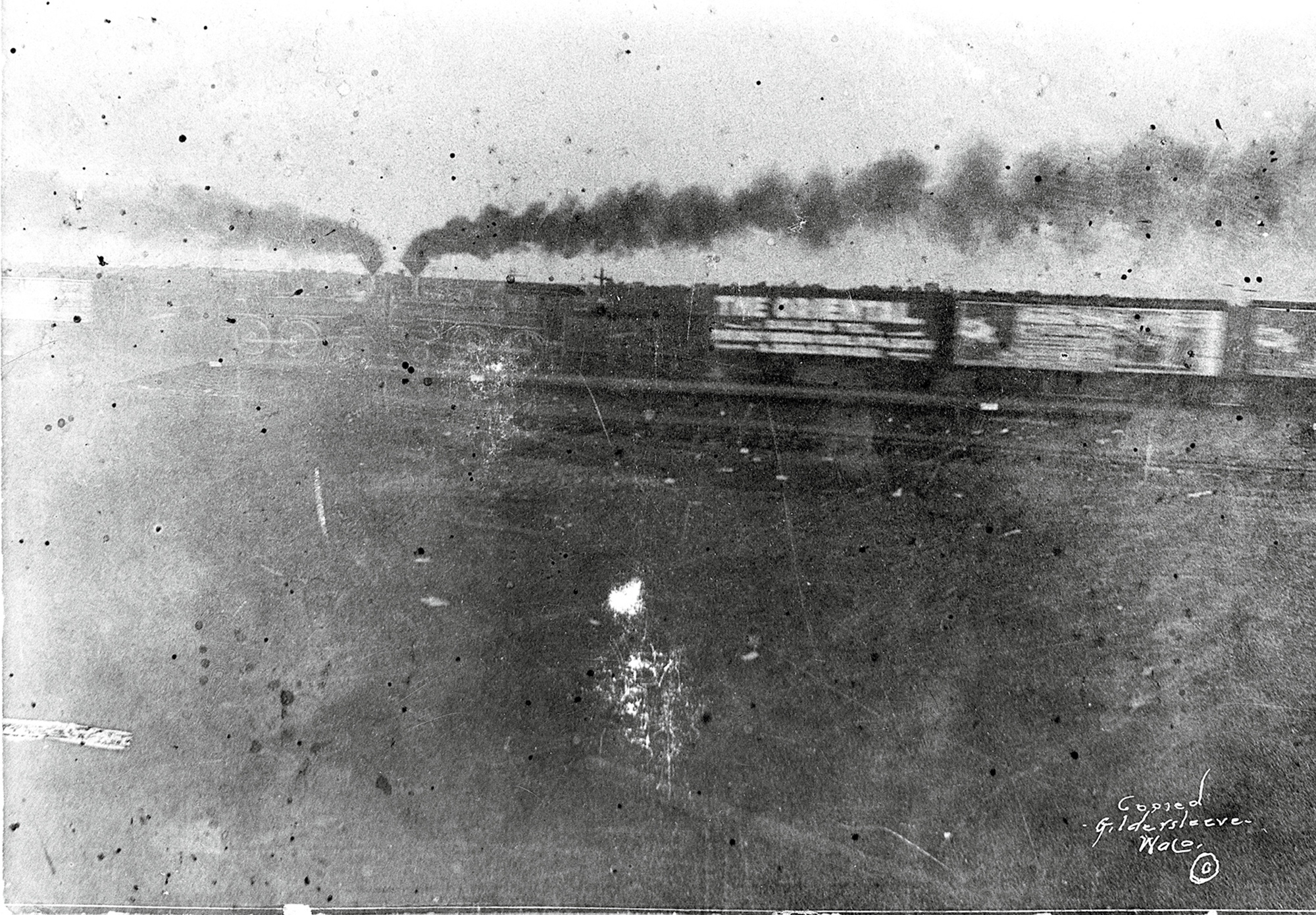

There are several photographs of the Crash at Crush, Texas, on 15 September 1896, but one of them is worth all the others put together. It has a thoroughly unreal quality, as if it is a prop from a hoax, or a Dadaist, futurist, or constructivist exercise in montage. But it’s real, and the moment it depicts was also real. Two steam locomotives, both blurred by speed and streaming smoke, hurtle towards each other. They are not “seconds from disaster,” they are at the precise instant of disaster, seemingly already touching, kissing, about to share the same space. The photographer hired for the occasion, Jervis Deane of Waco, Texas, would pay a high price for this astonishing image: debris from the smash blinded him in one eye.

It’s an unusual railway accident that has an official photographer, hired beforehand, but the Crash at Crush was a very unusual railway accident. Its mastermind was William George Crush, a passenger agent for the Missouri, Kansas and Texas Railway Company—the M-K-T or “Katy”—responsible for drumming up custom for the line. Crush knew the special appeal of catastrophe. He had seen the crowds that gathered to gawk at railway smashes, and may also have seen a prearranged collision of locomotives south of Columbus, Ohio, in the late spring of that year, which had drawn fifteen thousand spectators.[1] If he could stage a “monster wreck” on the Katy network and advertise it well in advance, he believed he could beat the Columbus crowds. And he wouldn’t even have to charge admission, as the company would profit from the thousands travelling to the event on Katy excursion trains. Under persistent pressure from Crush, the company’s management backed the scheme.

The site Crush selected for the crash was a shallow valley south of West, Texas, on the Katy line between Waco and Dallas. The valley afforded a natural amphitheater, which would host “Crush City,” a canvas conurbation with a 2,100-foot station platform, a carnival midway lined with honky-tonk attractions, two telegraph offices, five tanker cars dispensing water from a hundred faucets, a dozen “gigantic” lemonade stands, and a dining salon in a big top borrowed from Ringling Brothers Circus.[2] Two 1869 Baldwin locomotives, numbers 999 and 1001, were chosen from M-K-T rolling stock to die in the arena. One was painted green with red trim and the other red with green trim, and they toured the Katy network to publicize the event, through states Crush was busily papering with sensational posters. Word of the event spread across the country.