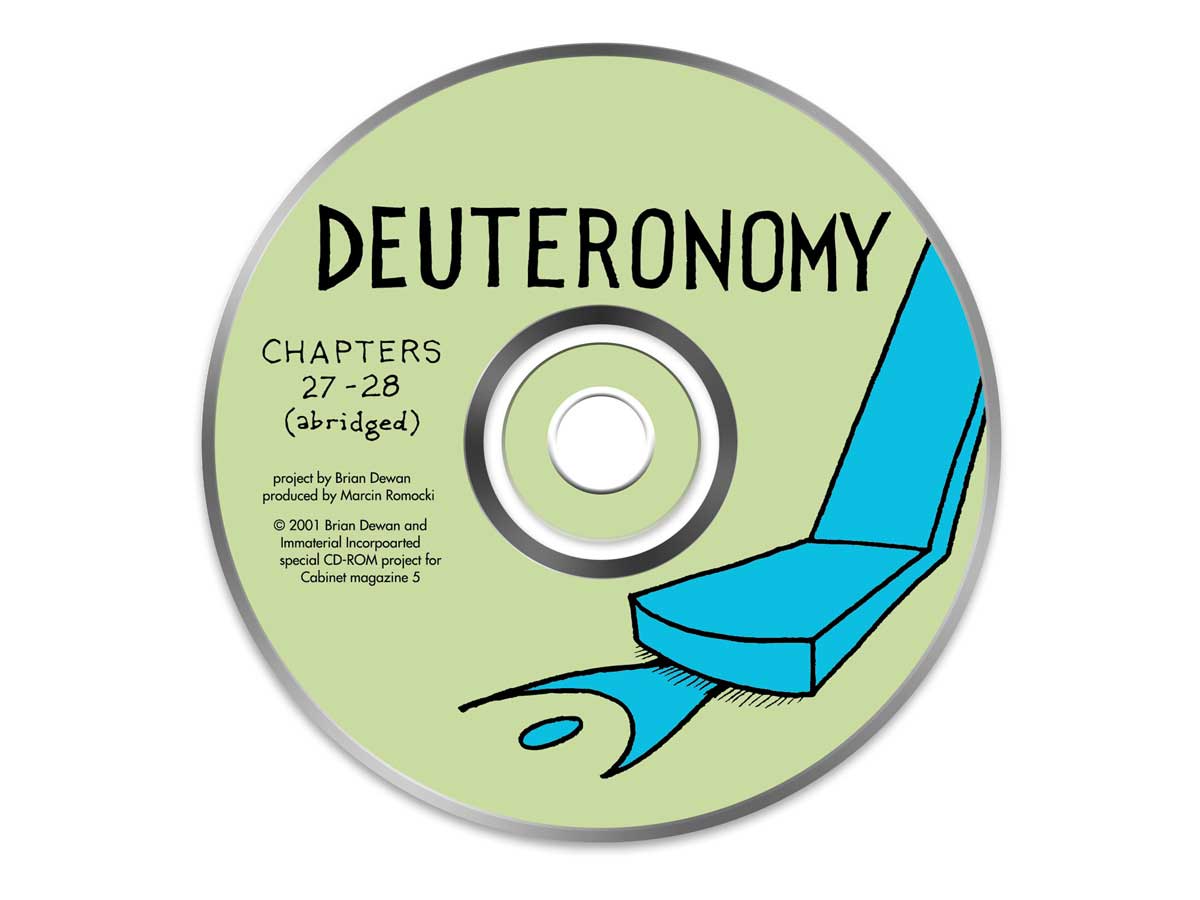

Artist Project: CD-ROM Insert / Deuteronomy

The ultimate educational filmstrip

Brian Dewan

Educational filmstrips enjoyed widespread use beginning in the 1920s and lasting through the 1970s. Filmstrips were an economical method of manufacturing a sequenced slide show printed on a single ribbon of sprocketed film. Early filmstrips featured illustrations or photographs with captions printed at the bottom—later they were supplemented with an accompanying phonograph record with narration and music. The record also dispatched a “beep” at intervals, which served to instruct the projector operator when to turn the crank and advance the filmstrip to the next frame. Presentations of this kind were popular in public schools as well as in religious education until they were supplanted by more complex and expensive electronic technologies.

Presented here is a filmstrip adapted for CD-ROM. A narrator reads from two chapters of the book of Deuteronomy while the viewer is shown colorful modern illustrations. Deuteronomy is the fifth and last book of the Pentateuch, the original five books of the Old Testament written by Moses. The book’s name means “second law,” which refers not to a new and unprecedented law but to a second articulation of Mosaic Law. Here, Moses elaborates on the Ten Commandments, explaining them in detail and offering hypothetical situations to which the law may be applied. He exhorts his people, chastises them, reminds them of their deliverance from slavery, and warns them of the danger of prosperity, “lest when you have eaten your fill … you become haughty of heart and unmindful of the Lord your God.”

The blessings bestowed on those who live in accordance with God’s commandments are starkly contrasted with the consequences, or curses, that are in store for those who do not. The text illustrates these consequences in great specificity—a deeply felt chronicle of how low one’s circumstances can sink. Plagues and blights, laboring in vain, the loss of property, and the capture of one’s offspring are among the many lavishly detailed possibilities outlined, interlaced with a horror of losing one’s social position or being displaced or subjugated by unfamiliar peoples.

The closing chapters of Deuteronomy are the final testimony of Moses shortly before his death:

Take this scroll of the law and put it beside the Ark of the Covenant of the Lord, your God, that there it may be a witness against you. For I already know how rebellious and stiff-necked you will be. Why, even now, while I am alive among you, you have been rebels against the Lord! How much more then, after I am dead! For I know that after my death you are sure to become corrupt and to turn aside from the way along which I directed you, so that evil will befall you in some future age because you have done evil in the Lord’s sight, and provoked him by your deeds.

(Deut. 31, 26–29)

The horror so unflinchingly expressed at the loss of control of one’s fortune and the absence of any kind of stability is echoed in Moses’s expectation that his people will inevitably fall into moral laxity despite the fact that the way has been shown them. Wisdom collected over the course of a lifetime, over generations of lifetimes, is a wealth the loss of which cannot be borne:

Take care and be earnestly on your guard not to forget the things which your own eyes have seen, nor let them slip from your memory as long as you live, but teach them to your children and to your children’s children.

(Deut. 4, 9–10)

Today, contemporary secular audiences will likely find the book of Deuteronomy to be unduly harsh or frightening, if not baffling. This perspective will likely be held in regard to most Old Testament writings or theological concepts in general. Though it may be challenging for modern persons to understand or appreciate the testimony of ancient persons, this empathy is what bridges the gulf that separates the generations.

Brian Dewan makes filmstrips, record albums, and instruments. He lives in Brooklyn.

Spotted an error? Email us at corrections at cabinetmagazine dot org.

If you’ve enjoyed the free articles that we offer on our site, please consider subscribing to our nonprofit magazine. You get twelve online issues and unlimited access to all our archives.